Working with a Full Deck: the Use of Picture Cards in Herpetological Surveys of Timor-Leste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

2019 Fry Trimeresurus Genus.Pdf

Toxicology Letters 316 (2019) 35–48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Toxicology Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/toxlet Clinical implications of differential antivenom efficacy in neutralising coagulotoxicity produced by venoms from species within the arboreal T viperid snake genus Trimeresurus ⁎ Jordan Debonoa, Mettine H.A. Bosb, Nathaniel Frankc, Bryan Frya, a Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, 4072, Australia b Division of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Einthoven Laboratory for Vascular and Regenerative Medicine, Leiden University Medical Center, Albinusdreef 2, 2333 ZA, Leiden, the Netherlands c Mtoxins, 1111 Washington Ave, Oshkosh, WI, 54901, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Snake envenomation globally is attributed to an ever-increasing human population encroaching into snake Venom territories. Responsible for many bites in Asia is the widespread genus Trimeresurus. While bites lead to hae- Coagulopathy morrhage, only a few species have had their venoms examined in detail. We found that Trimeresurus venom Fibrinogen causes haemorrhaging by cleaving fibrinogen in a pseudo-procoagulation manner to produce weak, unstable, Antivenom short-lived fibrin clots ultimately resulting in an overall anticoagulant effect due to fibrinogen depletion. The Phylogeny monovalent antivenom ‘Thai Red Cross Green Pit Viper antivenin’, varied in efficacy ranging from excellent neutralisation of T. albolabris venom through to T. gumprechti and T. mcgregori being poorly neutralised and T. hageni being unrecognised by the antivenom. While the results showing excellent neutralisation of some non-T. albolabris venoms (such as T. flavomaculaturs, T. fucatus, and T. macrops) needs to be confirmed with in vivo tests, conversely the antivenom failure T. -

Conservation Challenges Regarding Species Status Assessments in Biogeographically Complex Regions: Examples from Overexploited Reptiles of Indonesia KYLE J

Conservation challenges regarding species status assessments in biogeographically complex regions: examples from overexploited reptiles of Indonesia KYLE J. SHANEY, ELIJAH WOSTL, AMIR HAMIDY, NIA KURNIAWAN MICHAEL B. HARVEY and ERIC N. SMITH TABLE S1 Individual specimens used in taxonomic evaluation of Pseudocalotes tympanistriga, with their province of origin, latitude and longitude, museum ID numbers, and GenBank accession numbers. Museum ID GenBank Species Province Coordinates numbers accession Bronchocela cristatella Lampung -5.36079, 104.63215 UTA R 62895 KT180148 Bronchocela jubata Lampung -5.54653, 105.04678 UTA R 62896 KT180152 B. jubata Lampung -5.5525, 105.18384 UTA R 62897 KT180151 B. jubata Lampung -5.57861, 105.22708 UTA R 62898 KT180150 B. jubata Lampung -5.57861, 105.22708 UTA R 62899 KT180146 Calotes versicolor Jawa Barat -6.49597, 106.85198 UTA R 62861 KT180149 C. versicolor* NC009683.1 Gonocephalus sp. Lampung -5.2787, 104.56198 UTA R 60571 KT180144 Pseudocalotes cybelidermus Sumatra Selatan -4.90149, 104.13401 UTA R 60551 KT180139 P. cybelidermus Sumatra Selatan -4.90711, 104.1348 UTA R 60549 KT180140 Pseudocalotes guttalineatus Lampung -5.28105, 104.56183 UTA R 60540 KT180141 P. guttalineatus Sumatra Selatan -4.90681, 104.13457 UTA R 60501 KT180142 Pseudocalotes rhammanotus Lampung -4.9394, 103.85292 MZB 10804 KT180147 Pseudocalotes species 4 Sumatra Barat -2.04294, 101.31129 MZB 13295 KT211019 Pseudocalotes tympanistriga Jawa Barat -6.74181, 107.0061 UTA R 60544 KT180143 P. tympanistriga Jawa Barat -6.74181, 107.0061 UTA R 60547 KT180145 Pogona vitticeps* AB166795.1 *Entry to GenBank by previous authors TABLE S2 Reptile species currently believed to occur Java and Sumatra, Indonesia, with IUCN Red List status, and certainty of occurrence. -

On the Need to Follow Rigorously the Rules of the Code for the Subsequent Designation of a Nucleospecies

Zootaxa 2992: 1–51 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) On the need to follow rigorously the Rules of the Code for the subsequent designation of a nucleospecies (type species) for a nominal genus which lacked one: the case of the nominal genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 (Reptilia: Squamata: Viperidae) 1,4 2 3 PATRICK DAVID , GERNOT VOGEL & ALAIN DUBOIS 1Reptiles & Amphibiens, UMR 7205 OSEB, Département Systématique et Evolution, CP 30, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France; e-mail: [email protected] 2Society for Southeast Asian Herpetology, Im Sand 3, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] Reptiles & Amphibiens, UMR 7205 OSEB, 3Département Systématique et Evolution, CP 30, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France; e-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding Author Table of content Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Abbreviations . 3 Analysis of the case . 3 Early nomina of Asian green pitvipers . 3 Chronological analysis of publications relevant to the content and nucleospecies designation of Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 . 4 Discussion . 33 What is the nucleospecies of Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804? . 33 On the status of Trimeresurus viridis Lacépède, 1804 . 33 Nomenclatural implications . 35 The status of Trimeresurus viridis Lacépède, 1804 . 39 Conclusion . 39 Genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 . 40 Acknowledgements . 42 Literature cited . 42 Abstract This paper analyzes the consequences of the non-respect of the Rules of the Code to ascertain the valid subsequent desig- nation of the nucleospecies (type species) of the nominal genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804. -

Study of Species Richness and Structure Community of Herpetofauna on Kondang Merak Forest, Malang, Indonesia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347585507 Study of Species Richness and Structure Community of Herpetofauna on Kondang Merak Forest, Malang, Indonesia Conference Paper · January 2019 DOI: 10.5220/0009586100890095 CITATION READS 1 189 6 authors, including: Ahmad Muammar Kadafi M. Fathoni Universitas Palangka Raya Brawijaya University 9 PUBLICATIONS 6 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Muhammad Alif Fauzi Bagus Priambodo Brawijaya University State University of Malang 8 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS 23 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Understanding Snake Bite Cases Pattern Related to Volcano-Seismic Activity: An Evidence in Bondowoso, Indonesia View project Phylogeography of Trimeresurus View project All content following this page was uploaded by M. Fathoni on 24 December 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Study of Species Richness and Structure Community of Herpetofauna on Kondang Merak Forest, Malang, Indonesia Ahmad Muammar Kadafi1, M. Fathoni1, Muhammad Alif Fauzi1, Richo Firmansyah1, Bagus Priambodo2, Nia Kurniawan1,* 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Natural and Science, Brawijaya University, Malang 65145, East Java, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Natural and Science, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang 65145, East Java, Indonesia Keywords: Herpetofauna, Structure Community, Species Richness, Diversity, Kondang Merak Abstract: Kondang Merak Forest was known for its tourism destination, despite this area being the only coastal protected forest in Malang. Because of tourism demand, several anthropogenic activities were recorded and threatening the ecological balances of the forest including herpetofauna in it. -

Recent and Rapid Colonization of the Lesser Sundas Archipelago from Adjacent Sundaland 2 by Seven Amphibian and Reptile Species 3 4 SEAN B

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/571471; this version posted March 9, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Recent and rapid colonization of the Lesser Sundas Archipelago from adjacent Sundaland 2 by seven amphibian and reptile species 3 4 SEAN B. REILLY1*, ALEXANDER L. STUBBS1, BENJAMIN R. KARIN1, EVY ARIDA2, 5 DJOKO T. ISKANDAR3, JIMMY A. MCGUIRE1 6 7 1 Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, University of 8 California, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160 USA 9 2 Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jalan Raya Bogor- 10 Jakarta Km. 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia 11 3 School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung 10, Jalan 12 Ganesa, Bandung, Java 40132, Indonesia 13 14 *corresponding author 15 Sean B. Reilly 16 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology 17 University of California at Santa Cruz 18 130 McAllister Way, Santa Cruz, CA 95060 19 E-mail: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/571471; this version posted March 9, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Reilly et al. 2 20 Abstract 21 The Lesser Sundas Archipelago is comprised of two parallel chains of islands that extend 22 between the Asian continental shelf (Sundaland) and Australo-Papuan continental shelf (Sahul). 23 These islands have served as stepping-stones for taxa dispersing between the Asian and 24 Australo-Papuan biogeographic realms. -

Download Download

Kenya Luthfia Nur Shabrina, et al / Journal of Biology Education 9 (3) (2020): 275-282 Unnes.J.Biol.Educ. 9 (3) (2020) Journal of Biology Education http://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/ujbe The Video Effectiveness Based on Ethnobiology in Komodo Island as the Learning Media of PLH Kenya Luthfia Nur Shabrina1, Nur Kusuma Dewi1 1Biology Department, Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia Article Info Abstract Article History: This research was aimed to analyze the feasibility and effectiveness of video based on ethnobiology in Komodo Island as a learning media of PLH. Based on the result of observation Received: August 2020 in SMA 1 Bae Kudus, it needs a learning media that is based on ethnobiology in sustainable Accepted: September 2020 development subject matter and environmental pollution to help students in the learning process. Published: December 2020 This study was a R&D using one group pretest-posttest design which is done in SMA 1 Bae Kudus. The samples were from X MIPA 2 and X MIPA 3. The result of video eligibility Keywords: obtained an average value of 90.2% with very decent criteria. The result of the video Local wisdom, ethnobiology, effectiveness comes from students learning outcomes and conservation attitudes. It was proved learning media by the percentage of students classical completeness that had achieved the KKM ≥75 was 86.11% with medium to high criteria. Conservation attitude obtained an average yield of observers, friends and themselves at 83.79% with very high criteria. Students and teachers gave a good response to videos based on ethnobiology in Komodo Island. -

A New Species of Green Pit Vipers of the Genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 (Reptilia, Serpentes, Viperidae) from Western Arunachal Pradesh, India

Zoosyst. Evol. 96 (1) 2020, 123–138 | DOI 10.3897/zse.96.48431 A new species of green pit vipers of the genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 (Reptilia, Serpentes, Viperidae) from western Arunachal Pradesh, India Zeeshan A. Mirza1, Harshal S. Bhosale2, Pushkar U. Phansalkar3, Mandar Sawant2, Gaurang G. Gowande4,5, Harshil Patel6 1 National Centre for Biological Sciences, TIFR, Bangalore, Karnataka 560065, India 2 Bombay Natural History Society, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400001, India 3 A/2, Ajinkyanagari, Karvenagar, Pune, Maharashtra 411052, India 4 Annasaheb Kulkarni Department of Biodiversity, Abasaheb Garware College, Pune, Maharashtra 411004, India 5 Department of Biotechnology, Fergusson College, Pune, Maharashtra 411004, India 6 Department of Biosciences, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, Gujarat 395007, India http://zoobank.org/F4D892E1-4D68-4736-B103-F1662B7D344D Corresponding author: Zeeshan A. Mirza ([email protected]) Academic editor: Peter Bartsch ♦ Received 13 November 2019 ♦ Accepted 9 March 2020 ♦ Published 15 April 2020 Abstract A new species of green pit vipers of the genus Trimeresurus Lacépède, 1804 is described from the lowlands of western Arunachal Pradesh state of India. The new species, Trimeresurus salazar, is a member of the subgenus Trimeresurus, a relationship deduced contingent on two mitochondrial genes, 16S and ND4, and recovered as sister to Trimeresurus septentrionalis Kramer, 1977. The new species differs from the latter in bearing an orange to reddish stripe running from the lower border of the eye to the posterior part of the head in males, higher number of pterygoid and dentary teeth, and a short, bilobed hemipenis. Description of the new species and T. arunachalensis Captain, Deepak, Pandit, Bhatt & Athreya, 2019 from northeastern India in a span of less than one year highlights the need for dedicated surveys to document biodiversity across northeastern India. -

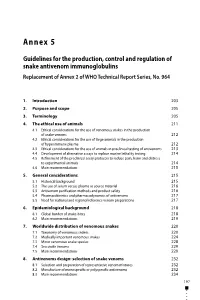

Guidelines for the Production, Control and Regulation of Snake Antivenom Immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No

Annex 5 Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom immunoglobulins Replacement of Annex 2 of WHO Technical Report Series, No. 964 1. Introduction 203 2. Purpose and scope 205 3. Terminology 205 4. The ethical use of animals 211 4.1 Ethical considerations for the use of venomous snakes in the production of snake venoms 212 4.2 Ethical considerations for the use of large animals in the production of hyperimmune plasma 212 4.3 Ethical considerations for the use of animals in preclinical testing of antivenoms 213 4.4 Development of alternative assays to replace murine lethality testing 214 4.5 Refinement of the preclinical assay protocols to reduce pain, harm and distress to experimental animals 214 4.6 Main recommendations 215 5. General considerations 215 5.1 Historical background 215 5.2 The use of serum versus plasma as source material 216 5.3 Antivenom purification methods and product safety 216 5.4 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antivenoms 217 5.5 Need for national and regional reference venom preparations 217 6. Epidemiological background 218 6.1 Global burden of snake-bites 218 6.2 Main recommendations 219 7. Worldwide distribution of venomous snakes 220 7.1 Taxonomy of venomous snakes 220 7.2 Medically important venomous snakes 224 7.3 Minor venomous snake species 228 7.4 Sea snake venoms 229 7.5 Main recommendations 229 8. Antivenoms design: selection of snake venoms 232 8.1 Selection and preparation of representative venom mixtures 232 8.2 Manufacture of monospecific or polyspecific antivenoms 232 8.3 Main recommendations 234 197 WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization Sixty-seventh report 9. -

Reported Primers

Russian Journal of Herpetology Vol. 26, No. 2, 2019, pp. 111 – 122 DOI: 10.30906/1026-2296-2019-26-2-111-122 A NEW SPECIES OF PITVIPER (SERPENTES: VIPERIDAE: Trimeresurus LACEPÈDE, 1804) FROM WEST KAMENG DISTRICT, ARUNACHAL PRADESH, INDIA Ashok Captain,1# V. Deepak,2,3# Rohan Pandit,4,7 Bharat Bhatt,5 and Ramana Athreya6,7* Submitted August 13, 2018 A new species of pitviper, Trimeresurus arunachalensis sp. nov., is described based on a single specimen. It differs from all known congeners by the following combination of characters — 19:17:15 acutely keeled dorsal scale rows (except first row — keeled or smooth); overall reddish-brown coloration; white dorsolateral stripe on outer posterior edges of ventrals and sometimes first dorsal scale row; 7 supralabials; 6 – 7 scales between supraoculars; 145 ventrals; 51 paired subcaudals (excluding the terminal scale); single anal; a sharply defined canthus rostralis with the margin overhanging the loreal region; a distinctly concave rostral scale with the upper edge projecting well beyond its lower margin; an unforked, attenuate hemipenis that extends to the 8th subcaudal scale, and has no visible spines. DNA phylogenetic analysis indicates that the new species is distinct from congeners and nested well within the Trimeresurus clade. The closest relative based on available DNA data is T. tibetanus. The new spe- cies is presently known from a single locality — Ramda, West Kameng, Arunachal Pradesh, northeastern India. Keywords: Crotalinae; snake; taxonomy; Trimeresurus arunachalensis sp. nov.; viper. INTRODUCTION 1804) comprising more than 90 species in total, Trimere- surus is the most diverse group with 50 known species Of the eight genera of pitvipers found in Asia (Callo- distributed across south and south-east Asia (e.g., Uetz et selasma Cope, 1860; Deinagkistrodon Gloyd, 1979; al., 2018). -

JELS 9(1) 2019 with Cover.Pdf

ISSN. 2087-2852 E-ISSN. 2338-1655 The Journal of Experimental Life Science Discovering Living System Concept through Nano, Molecular and Cellular Biology Editorial Board Chief Editor Dian Siswanto, S.Si., M.Sc., M.Si., Ph.D Editorial Board Aida Sartimbul, M.Sc. Ph.D - UB Sukoso, Prof. MSc. Ph.D-UB Adi Santoso, M.Sc. Ph.D - LIPI Etik Mardliyati, Dr. - BPPT Nurul Taufiq, M.Sc. Ph.D - BPPT Soemarno, Ir., MS., Dr., Prof. - UB Arifin Nur Sugiharto, M.Sc. Ph.D -UB M. Sasmito Djati, Ir., MS., Dr., Prof. - UB Reviewers Aris Soewondo, Drs., M.Si – UB Andi Kurniawan, S.Pi, M.Eng, D.Sc. - UB Muhaimin Rifai, Ph.D., Prof. – UB Suharjono, MS., Dr. - UB Sri Rahayu, M.Kes., Dr. – UB Attabik Mukhammad Amrillah, S.Pi., M.Si - UB Dina Wahyu Indriani, STP., MSc. – UB Indah Yanti, S.Si., M.Si. - UB Widodo, S.Si., M.Si., Ph.D MED Sc., Prof. – UB Yoga Dwi Jatmiko, S.Si., M.App.Sc., Ph.D. - UB Moch. Sasmito Djati, Ir., MS, Dr., Prof. – UB Catur Retnaningdyah, Dra,. M.Si., Dr. - UB Nia Kurniawan, S.Si.,MP.,D.Sc – UB Mohammad Amin, SPd., M.Si., Dr. Agr., Prof. - UM Retno Mastuti, Ir., M.Agr.Sc., D.Agr.Sc – UB Bagyo Yanuwiadi, Dr. – UB Sutiman Bambang S., Dr., Prof. - UB Muhamad Firdaus, Ir., MP., Dr. - UB Irfan Mustafa, S.Si.,M.Si.,Ph.D - UB Yuni Kilawati, S.Pi., M.Si., Dr. – UB Mufidah Afiyanti, Ph.D. – UB Amin Setyo Leksono, S.Si.,M.Si.,Ph.D - UB Estri Laras Arumingtyas, Dr., Prof. -

Tingkat Kejadian Dan Identifikasi

IR – PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA BAB 1 PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Ular hijau (Trimeresurus insularis) salah satu spesies dari genus Trimeresurus yang memiliki penyebaran yang luas dikenal juga dengan nama lain White-lipped Green Pitviper. T.insularis termasuk reptil arboreal yang tersebar di Pulau Jawa, Bali, Flores, Komodo, Lombok, Sumba (Priambodo, 2019). Ular hijau (T.insularis) tergolong hewan crepuscular yang aktif dalam mencari makanan pada saat intensitas cahaya matahari tidak dalam keadaan penuh (Reilly, 2016). Ular hijau (T.insularis) yang hidup bebas di alam dengan status list concern saat ini sudah dimanfaatkan sebagai salah satu exotic pet (IUCN red list 2010). Standard manajemen pemeliharaan dari segi pakan merupakan salah satu faktor resiko tertinggi yang menyebabkan kejadian penyakit parasitik yaitu infeksi cacing atau yang disebut dengan helminthiasis (Kolodziej et al., 2018). Kasus helminthiasis dapat mempengaruhi tingkat populasi ular hijau (T.insularis) yang akan berdampak pada menurunnya jumlah populasi, hal ini disebabkan karena sulitnya melakukan pengendalian pada ular hijau yang hidup di alam. Usaha pengendalian hanya dapat dilakukan pada ular hijau (T.insularis) yang sudah dijadikan exotic pet. Kejadian infeksi cacing Cestoda pada ular sudah pernah dilaporkan di Indonesia salah satunya adalah infeksi dari genus Spirometra (Pranashinta, 2017). Spirometra adalah cacing dari kelas cestoda berbentuk pipih dan pada setiap segmen memiliki interproglotid gland sebagai organ reproduksi. Siklus hidup cacing Spirometra cukup kompleks dengan membutuhkan beberapa inang. Siklus 1 SKRIPSI TINGKAT KEJADIAN DAN IDENTIFIKASI... CAHAYA C. J. P. 2 IR – PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA hidup Spirometra dimulai ketika telur yang berembrio jatuh ke air bersama feses inang defenitif yaitu karnivora dan akan berkembang menjadi coracidium yang selanjutnya termakan oleh copepod dan pada saluran cerna berkembang menjadi stadium procercoid, pada stadium infektif (plerocercoid) Spirometra membutuhkan inang paratenik yaitu reptil, amphibi, dan unggas.