Revisiting the Geometry of the Sala De Dos Hermanas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USA OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753

11.12.2017 LISTE DES EXPORTATEURS ET IMPORTATEURS D’HUILES D’OLIVE, D’HUILES DE GRIGNONS D’OLIVE ET D’OLIVES DE TABLE LIST OF EXPORTERS AND IMPORTERS OF OLIVE OILS, OLIVE-POMACE OILS AND TABLE OLIVES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/ÉTATS-UNIS D’AMÉRIQUE ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY NORTH AMERICAN OLIVE 3301 Route 66 – Suite 205, USA www.naooa.org OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753 ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. SPAIN www.acesur.com 550,6 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla SPAIN s/n 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR Camino Alcoba, s/n SPAIN www.agolives.com S.L. 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN www.aceitunasmontegil.es 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 SPAIN 41510 MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, SPAIN S.A. 14 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. SPAIN www.acolsa.es S.A. IV Km. 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AEGEAN STAR FOOD Kral Incir Isletmesi TURKEY www.aegeanstar.com.tr INDUSTRY TRADE LTD. Dallica Mevkii 09800 NAZ AGRICOLA I CAIXA Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com AGRARIA SC CAMBRILS 43850 CAMBRILS SCCL (Tarragona) 2 ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY AGRITALIA S.R.L. -

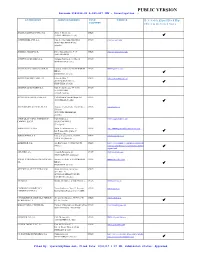

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation - ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE Believed to Export Black Ripe COUNTRY Olives to the United States ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. 550,6 SPAIN www.acesur.com 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla s/n SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR S.L. Camino Alcoba, s/n 41530 MORON SPAIN www.agolives.com DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN http://www.montegil.es/ 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 41510 SPAIN MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS S.A. Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, 14 SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, S.A. Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. IV Km. SPAIN www.acolsa.es 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AGRICOLA I CAIXA AGRARIA SC Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com CAMBRILS SCCL 43850 CAMBRILS (Tarragona) AGRO SEVILLA USA Avda. de la Innovación, s/n SPAIN http://www.agrosevilla.com/en/contact/ Ed. Rentasevilla, planta 8ª 41020 Sevilla AGRUCAPERS, S.A. Ctra. de Lorca, Km 3,2 30880 SPAIN www.agrucapers.es AGUILAS (Murcia) ALMINTER, S.A. Av. Río Segura, 9 30562 CEUTI SPAIN http://www.aliminter.com/index.php/produ (Murcia) ctos-nacional/bangor-encurtidos/aceitunas- negras.html AMANIDA SA Avenida Zaragoza, 83 SPAIN www.amanida.com 50630 ALAGON (Zaragoza) ANGEL CAMACHO ALIMENTACION, Avenida del Pilar, 6 41530 MORON SPAIN www.acamacho.com S.L. -

Achila, Visigothic King, 34 Acisclus, Córdoban Martyr, 158 Adams

Index ; Achila, Visigothic king, 34 Almodóvar del Río, Spain, 123–24 Acisclus, Córdoban martyr, 158 Almonacid de la Cuba, Spain, 150. See Adams, Robert, 21 also Dams Aemilian, St., 160 Alonso de la Sierra, Juan, 97 Aerial photography, 40, 82 Amalaric, Visigothic king, 29–30, 132, Aetius, Roman general, 173–75 157 Africa, 4, 21–23; and amphorae, 116, Amber, 114 137, 187, 196; and ARS, 46, 56, 90, Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman histo- 99, 187; and Byzantine reconquest, rian, 166, 168 30; and ‹shing, 103; and olive oil, Amphorae, 43, 80, 199–200; exported 88, 188; and Roman army, 114, 127, from Spain, 44, 97–98, 113, 115–16, 166; and trade, 105, 141; and Van- 172; kilns, 61–62, 87–90, 184; from dals, 27–28, 97, 127, 174 North Africa, 129, 187. See also African Red Slip (ARS) pottery, 101, Kilns 147, 186–87, 191, 197; de‹nition, 41, Anderson, Perry, 5 43, 44, 46; and site survival, 90, Andujar, Spain, 38, 47, 63 92–95, 98–99; and trade, 105–6, 110, Annales, 8, 12, 39 114, 116, 129, 183 Annona: disruption by Vandals, 97, Agde, council of, 29, 36, 41 174; to Roman army, 44, 81, 114–17; Agglomeration, 40–42, 59, 92 to Rome, 23, 27, 44, 81, 113; under Agila, Visigothic king, 158–59. See Ostrogoths, 29, 133. See also Army also Athanagild Antioch, Syria, 126 Agrippa, Roman general, 118 Anti-Semitism, 12, 33. See also Jews Alans, 24, 26, 27, 34, 126, 175 Antonine Itinerary, 152 Alaric, Visigothic king, 2, 5, 26–27 Apuleius, Roman writer, 75–76, 122 Alaric II, Visigothic king, 29–30 Aqueducts, 119, 130, 134, 174–75 Alcalá del Río, Spain, 40, 44, 93, 123, Aquitaine, France, 2, 27, 45, 102 148 Arabs, 33–34, 132–33, 137. -

C31a Die 15I V I L L $

~°rOV17 C31a die 15i V I L L $ Comprende esta provincia los siguientes Municipios por partidos judiciales . Partido de Carmona . Partido de Morán de la, Frontera. Campana (La) . AL-tirada del Alear . Algamitas . Morón de la Frontera . Coripe . r mona . Viso del Alcor (El) Pruna. Coronil (El) . Montellano . Puebla de Cazalla (La) . Partido de Cazalla de a Sierra . Partido de Osuna . Alarde . Na•,'a .s de la Concepció n Altuadén de la Plata . (Las) . Cazalla de le Sierra, 1'('dro .so (El) . Cunslantina, lleal de la . Jara (El) . Corrales (Los) . Rubio (El) . (Iemlalee ia , San Nieol ;ís del Puerto Lantejuela (La.) . Naucejo (BO . Martín (le la Jara . Osuna . Villanueve de San Juau . Partido de Écija. Partido de Sanlúcar la Mayor. Coija . ? .uieie(ia . (L,e fuentes de Andalucía . Alhaida de Aljarafe . Madroño (PIl} . Aznalcázar . Olivares . Aznalcóllar. Pilas. Partido de Estepa. IJenacazón . Ronquillo (El) . ('arrión de los Céspedes. Saltaras. Castilleja del Campo . Sanlúcar lal Mayor. Castillo de las Guarda s ITmbrete. Aguadulee . I Ferrera .. (El) . Villamanrique de la Con - Itadolatosa . Lora de Estepa, - Iüspartinas . lesa. Casariche, Marinaleda . ifuévar . Villanueva del Ariseal . Estepa . Pedrera, (Mena .. Roda ale Andalucía (Lo ) Partidos (cinco) de Sevilla . Partido de Lora del Río . Alardea del Río . Puebla de les. Infantes Alead -1 del Río . (La) . Gel ves . (°antillana . Algaba (La) . Tetina . Gerena Atmensilla . Gines ora del Río . Villanueva del 'Rfo . llollullos de la Mitación 1' ileflor . t'illaverde del Río . Guillada. llormujos . M-airena . del Aljarafe _ Tiranas . Palomares del Rfo . liurguillo .. Puebla del Río (La} . Camas. Rinconada (La) . Partido de Marchena . Castilblaneo de los Arro- San Juan de Azna1f- .,a s yos . -

Torneo Ciudad De Dos Hermanas – Kasparov Not Winning!

Torneo Ciudad de Dos Hermanas – Kasparov not winning! Year Champion Country Points 1989 cat. 3 Julian Hodgson (already GM) England 7'5/9 (first edition) Leonid Bass (on tie-break, IM, then and today) USA 1990 cat. 5 7/9 Mark Hebden (IM then, later GM) England Alexander Goldin (already GM) 1991 cat. 7 Russia 7'5/9 (2. Granda Zuniga, 3.= Bass) Leonid Yudasin 1992 cat. 11 Israel 7/9 (2. Akopian, 5. Pia Cramling; 8. Hodgson) Anatoly Karpov 1993 cat. 13 Russia 7'5/9 (2. Judit Polgar, 3.= Epishin, Khalifman) Boris Gelfand 1994 cat. 16 Belarus 6'5/9 (2. Karpov, 3. Epishin, 4. Topalov) Gata Kamsky (on tie-break) Anatoly Karpov, second win USA 1995 cat. 18 Michael Adams Russia 5'5/9 supertorneo (4.-5. Gelfand, Judit Polgar, 6.-7. Lautier, England Illescas, 8. Piket, 9. Salov, 10. Shirov.) Vladimir Kramnik (on tie-break) 1996 cat. 19 Veselin Topalov supertorneo Russia (3.-4. Anand, ➔ Kasparov half a point behind, 6/9 (nine of the top ten Bulgaria 5. Illescas, 6.-7. Kamsky, Gelfand, 8. Ivanchuk, Elo ranked player!) 9.-10. Shirov, Judit Polgar) Viswanathan Anand (on tie-break) 1997 cat. 19 Vladimir Kramnik, second win India 6/9 supertorneo (3.-5. Salov, Karpov, Topalov, 6.-8. Judit Polgar, Gelfand, Shirov, 9. Short, 10. Illescas) 1998 (no tournament) 1999 cat. 18 / 19 Michael Adams, second win supertorneo (2. Kramnik; 3./4. Illescas, Topalov, 5./6. (10th and Gelfand, Karpov, 7. Korchnoi; 8.-10. Svidler, jubilee edition, Judit Polgar, and the title defender, top-seeded England 6/9 Adams surpass Anand as joint last, remaining the only player three former & without a single game win! Korchnoi was 68. -

La Alhambra in Granada, One of the Most Beautiful and Admired Monuments in the Wold

La Alhambra in Granada, one of the most beautiful and admired monuments in the wold. An old legend says that the Alhambra was built by night, in the light of torches. Its reddish dawn did believe the people of Grenada that the color was like the strength of the blood. The Alhambra, a monument of Granada for Spain and the world. La Alhambra was so called because of its reddish walls (in Arabic, («qa'lat al-Hamra'» means Red Castle ). It is located on top of the hill al-Sabika, on the left bank of the river Darro, to the west of the city of Granada and in front of the neighbourhoods of the Albaicin and of the Alcazaba. The Alhambra is one of the most serenely sensual and beautiful buildings in the world, a place where Moorish art and architecture reached their pinnacle. A masterpiece for you to admire, and it is in Granada, a city full of culture and history. Experience the beauty and admire this marvel of our architectural heritage. Let it touch your heart. Granada is the Alhambra and the gardens, the Cathedral, the Royal Chapel, convents and monasteries, the old islamic district Albayzin where the sunset is famous in the world or the Sacromonte where the gypsies perform flamenco shows in the caves where they used to live...Granada is this and many more things. The Alhambra is located on a strategic point in Granada city, with a view over the whole city and the meadow ( la Vega ), and this fact leads to believe that other buildings were already on that site before the Muslims arrived. -

AYUNTAMIENTO DE GINES Delegación De Festejos ORDEN

AYUNTAMIENTO DE GINES Delegación de Festejos ORDEN DE ACTUACIÓN DURANTE LA FASE PREVIA DEL CERTAMEN CARNAVALESCO DE AGRUPACIONES EN GINES (CECAG 2018) PRIMERA SEMIFINAL DEL CONCURSO DE AGRUPACIONES CARNAVALESCAS Jueves 15 de febrero, 19.30 horas Casa de la Cultura “El Tronío” (por orden de actuación) 1. Chirigota. ¡AQUÍ NO HAY QUIEN VIVA MAMÁ! Dos Hermanas 2. Chirigota. HOY NO ME PUEDO AGACHAR. Coria del Río 3. Comparsa. CON CUATRO TRAPOS. Punta Umbría (Hueva) (descanso) 4. Chirigota. ¡QUÉ ME DICES! Sanlúcar la Mayor 5. Comparsa. LOS ENCANTADORES. Ronda (Málaga) 6. Comparsa. LA PLAYA. Conil (Cádiz) 7. Comparsa. EL ORO NEGRO. Cádiz SEGUNDA SEMIFINAL DEL CONCURSO DE AGRUPACIONES CARNAVALESCAS Viernes 16 de febrero, 19.30 horas Casa de la Cultura “El Tronío” (por orden de actuación) 1. Chirigota. ANDALUCES DE PEDIGREE. Alcalá de Guadaíra 2. Comparsa. LOS DESTRONADOS. Dos Hermanas 3. Cuarteto. ¿AHORA ME VES...? Utrera 4. Comparsa. LA CUMBRE. Alcalá Guadaíra 5. Chirigota. NOS VAMOS A CORRER. Alcalá de Guadaíra (descanso) 6. Chirigota. LAS NIÑAS DE JOSÉ LUIS. Gines 7. Comparsa. LA TORMENTA PERFECTA. Dos Hermanas 8. Chirigota. ¡OJÚ QUE PENITA DE PATIO! Écija 9. Comparsa. LOS PASTORES. Fuentes de Cantos (Badajoz) TERCERA SEMIFINAL DEL CONCURSO DE AGRUPACIONES CARNAVALESCAS Sábado 17 de febrero, 19.30 horas Casa de la Cultura “El Tronío” (por orden de actuación) 1. Chirigota. UNA CHIRIGOTA MALA MALA DE VERDAD. Los Palacios 2. Comparsa. LA GLORIA. Alcalá de Guadaíra 3. Cuarteto. EL DOMINGO CON CHALEQUITO-CUARTETO HOMENAJE. Gines 4. Comparsa. HOTEL PARAÍSO. Sevilla 5. Comparsa. LA FORTALEZA. Las Cabezas de San Juan (descanso) 6. Chirigota. QUÉ LASTIMA DE MAÑANA DESPERDICIÁ. -

65 – Alhambra. Granada, Spain. Nasrid Dynasty. 1354-1391 C.E., Whitewashed Adobe, Stucco, Wood, Tile, Paint, and Gilding

65 – Alhambra. Granada, Spain. Nasrid Dynasty. 1354-1391 C.E., Whitewashed adobe, stucco, wood, tile, paint, and gilding. (4 images) “the red female” – reflects the color of red clay of which the fort is made built originally as a medieval stronghold – castle, palace, and residential annex for subordinates o citadel is the oldest part, then the Moorish rulers(Nasrid) palaces . palace of Charles V (smaller Renaissance) built where part of the original Alhambra (including original main entrance) was torn down Royal complex had (for the wives and mistresses): running water (cold and hot) and pressurized water for showering – bathroom were open to the elements to allow light and air Court of the Lions o Oblong courtyard (116 x 66 ft) with surrounding gallery supported on 124 white marble columns (irregularly placed), filigree wall o Fountain – figures of twelve lions: symbols of strength, power, and sovereignty . Poem on fountain (written by Ibn Zamrak) praises the beauty of fountain and the power of the lions and describes the ingeious hydraulic systems –which baffled all who saw them (that made each of the lions in turn produce water from its mouth – one each hour) reflection of the culture of the last centuries of the Moorish rule of Al Andalus, reduced to the Nasrid Emirate of Granada (conquered by Spanish Christians in 1392) Artistic choices: reproduced the same forms and trends + creating a new style o Isolation from rest of Islam + relations with Christian kingdoms influenced building styles o No master plan for the total site o Muslim art in its final European stages – only consistent theme: “paradise on earth” o Red, blue, and a golden yellow (faded by time and exposure) are main colors o Decoration: mostly Arabic inscriptions made into geometric patterns made into arabesques (rhythmic linear patterns) Court of the Lions Hall of the Sisters . -

Boletín Oficial De La Provincia De Sevilla

U T A C I I P O N D DE Boletín S E V I L L A Oficial de la provincia de Sevilla Publicación diaria, excepto festivos — Franqueo concertado número 41/2 — Depósito Legal SE–1–1958 Martes 27 de enero de 2004 Número 21 T.G.S.S. 377 ESTE NÚMERO CONSTA DE DOS FASCÍCULOS FASCÍCULO PRIMERO Sumario JUNTA ELECTORAL PROVINCIAL: Constitución de la Junta Electoral Provincial de Sevilla . 966 JUNTAS ELECTORALES DE ZONA: Constitución de las Juntas Electorales de Zona de Sevi- lla, Lora del Río y Marchena . 966 DELEGACIÓN DEL GOBIERNO EN ANDALUCÍA: — Subdelegación del Gobierno en Sevilla: Notificaciones . 966 JUNTA DE ANDALUCÍA: — Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes: Delegación Provincial de Sevilla: Expedientes de expropiación forzosa . 971 TESORERÍA GENERAL DE LA SEGURIDAD SOCIAL: — Dirección Provincial de Sevilla: Servicio Técnico de Notificaciones e Impugnaciones: Relación de deudores . 974 BOP 966 Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Sevilla. Número 21 Martes 27 de enero de 2004 JUNTA ELECTORAL PROVINCIAL LORA DEL RÍO ——— Con arreglo a lo establecido en el artículo 14.3 de la L.O. 5/85, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General, SEVILLA comunico la relación de miembros de la Junta Electoral Don Eloy Méndez Martínez, Presidente de esta Junta de Zona de Lora del Río, para su inserción en el «Boletín Electoral Provincial. Oficial» de la provincia de Sevilla y en el «Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía», interesándose se remita ejem- Hago saber: Que en el día de hoy ha quedado consti- plar del número en que sea publicado. -

Gener Sex Categ Dors Apellidos Y Nombre Tiempo Med/Km Categoria Sexo Club Localidad 1 1 1 1122 Bangoura Alhassane 1:24:12 3:14 Senior M C.A

GENER SEX CATEG DORS APELLIDOS Y NOMBRE TIEMPO MED/KM CATEGORIA SEXO CLUB LOCALIDAD 1 1 1 1122 BANGOURA ALHASSANE 1:24:12 3:14 SENIOR M C.A. MAURI CASTILLO SEVILLA 2 2 1 260 ROSA ARANDA MANUEL 1:27:03 3:20 VETERANO A M C.A. ASTIGI ECIJA 3 3 2 913 MUÑOZ PEREZ ANGEL 1:27:25 3:21 SENIOR M C.D. BIKILA GRANADA POZOBLANCO 4 4 1 1021 DIAZ CARRETERO JAVIER 1:27:55 3:22 VETERANO B M C.A. SAN PEDRO SAN PEDRO ALCANTARA 5 5 2 284 GOMEZ-SERRANILLOS CALDERON JUSTO 1:28:03 3:23 VETERANO A M SEVILLA MANUEL 6 6 3 103 ALARCON LEON MIGUEL 1:29:22 3:26 SENIOR M C.A. ASTIGI ECIJA 7 7 4 635 BOUALLA BOUALLA IBRAHIM 1:30:01 3:27 SENIOR M AMO ALLA AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA 8 8 5 814 BURGOS LEBRIJA ANTONIO 1:30:42 3:29 SENIOR M C.A. MARATON MARCHENA MARCHENA 9 9 3 760 GONZALEZ MALDONADO JESUS RAFAEL 1:30:50 3:29 VETERANO A M LORA DEL RIO 10 10 2 1090 EIRE GUTIERREZ JAVIER 1:30:57 3:29 VETERANO B M C.A. GERENA GERENA 11 11 6 1051 DE LA TORRE GARCIA GARCIA FRAN 1:31:48 3:31 SENIOR M C.D. LOS CALIFAS GUADALCAZAR 12 12 4 927 GOMEZ IGLESIAS JOSE LUIS 1:32:45 3:34 VETERANO A M E.P.A. MIGUEL RIOS LA RINCONADA 13 13 5 900 HOYA BAUTISTA MANUEL 1:32:48 3:34 VETERANO A M E.P.A. -

Dos Hermanas, Utrera, Lebrija, Osuna Y Écija Tendrán

Isabel Joaquín Fabio Pantoja McNamara Se confiesa Sabina «Muchas frases hoy en Cuatro «La coca es tan de las películas con Concha mala aquí que de Almodóvar García Campoy fue fácil dejarla» eran mías» Página 26 Página 20 Página 21 Dos Hermanas, Utrera, Lebrija, Osuna y Écija El primer diario que no se vende tendrán ‘botellódromo’ Jueves 30 NOVIEMBRE DE 2006. AÑO VII. NÚMERO 1595 Los cinco municipios sevillanos se suman a la capital y fijan un lugar donde se permitirá beber en la vía pública. En las demás localidades no hay nada previsto, Las obras para sustituir la cárcel de la Ranilla por un parque arrancan en enero ya que sus ayuntamientos aseguran que «éste no es un fenómeno extendido». 2 Contará también un centro cívico, la sede de la Po- licía Local y un museo de la memoria histórica. 3 Los estudiantes podrán seguir sus quejas en la web del Defensor del Universitario Estará en funcionamiento el próximo mes en la US. 2 La Junta lanza las becas Talentia para estudiar en Harvard, Yale, la Sorbona... Y hasta cien universidades más. Cubrirán gastos de posgrados y másters. Habrá 100 en 2007. 4 KAKO RANGEL Accidente químico de pega Doscientas personas participaron en un si- mulacro de accidente de un camión cargado de sustancias peligrosas en pleno Sevilla. 2 Detenido un profesor que obligaba a niñas a desnudarse para grabarlas EL DOLOR DE UNA VIUDA Ana Iríbar, viuda del concejal del PP Gregorio Ordóñez, ayer en el juicio por el asesinato de su marido, en 1995, a manos de ETA. -

Islamic Architecture Islam Arose in the Early Seventh Century Under the Leadership of the Prophet Muhammad

Islamic Architecture Islam arose in the early seventh century under the leadership of the prophet Muhammad. (In Arabic the word Islam means "submission" [to God].) It is the youngest of the world’s three great monotheistic religions and follows in the prophetic tradition of Judaism and Christianity. Muhammad leads Abraham, Moses and Jesus in prayer. From medieval Persian manuscript Muhammad (ca. 572-632) prophet and founder of Islam. Born in Mecca (Saudi Arabia) into a noble Quraysh clan, he was orphaned at an early age. He grew up to be a successful merchant, then according to tradition, he was visited by the angel Gabriel, who informed him that he was the messenger of God. His revelations and teachings, recorded in the Qur'an, are the basis of Islam. Muhammad (with vailed face) at the Ka'ba from Siyer-i Nebi, a 16th-century Ottoman manuscript. Illustration by Nakkaş Osman Five pillars of Islam: 1. The profession of faith in the one God and in Muhammad as his Prophet 2. Prayer five times a day 3. The giving of alms to the poor 4. Fasting during the month of Ramadan 5. The hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca Kaaba - the shrine in Mecca that Muslims face when they pray. It is built around the famous Black Stone, and it is said to have been built by Abraham and his son, Ishmael. It is the focus and goal of all Muslim pilgrims when they make their way to Mecca during their pilgrimage – the Hajj. Muslims believe that the "black stone” is a special divine meteorite, that fell at the foot of Adam and Eve.