Achila, Visigothic King, 34 Acisclus, Córdoban Martyr, 158 Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MJMES Volume VIII

Volume VIII 2005-2006 McGill Journal of Middle East Studies Revue d’études du Moyen-Orient de McGill MCGILL JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST STUDIES LA REVUE D’ÉTUDES DU MOYEN- ORIENT DE MCGILL A publication of the McGill Middle East Studies Students’ Association Volume VIII, 2005-2006 ISSN 1206-0712 Cover photo by Torie Partridge Copyright © 2006 by the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies A note from the editors: The Mandate of the McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is to demonstrate the dynamic variety and depth of scholarship present within the McGill student community. Staff and contributors come from both the Graduate and Undergraduate Faculties and have backgrounds ranging from Middle East and Islamic Studies to Economics and Political Science. As in previous issues, we have attempted to bring this multifaceted approach to bear on matters pertinent to the region. *** The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies is registered with the National Library of Canada (ISSN 1206-0712). We have regularized the subscription rates as follows: $15.00 Canadian per issue (subject to availability), plus $3.00 Canadian for international shipping. *** Please address all inquiries, comments, and subscription requests to: The McGill Journal of Middle East Studies c/o MESSA Stephen Leacock Building, Room 414 855 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 2T7 Editors-in-chief Aliza Landes Ariana Markowitz Layout Editor Ariana Markowitz Financial Managers Morrissa Golden Avigail Shai Editorial Board Kristian Chartier Laura Etheredge Tamar Gefen Morrissa Golden -

Recent Archaeological Research at Asturica Augusta

Proceedings of the British Academy, 86, 371-394 Recent Archaeological Research at Asturica Augusta VICTORINO GARCfA MARCOS & JULIO M. VIDAL ENCINAS Iunguntur iis Asturum XXII populi divisi in Augustanos et Transmontanos, Asturica urbe magnifica (..) (Pliny NH 3.28). OVERTHE LAST 10 YEARS, as the result of the delegation of the management of cultural affairs to the Autonomous Community of Castilla y Le6n, uninterrupted rescue excavations have taken place in the town of Astorga, Roman Asturica Augusta (Vidal 1986a and 1986b; Garcia and Vidal1990; Vidal et al. 1990, 259-63; Garcla and Vidal 1993; Tab. Imp. Rom. 1991, 27-9; Vidal 1993, 309-12; Fernhndez 1993, 227-31; Garcia 1994). At the same time, rescue excavations have also taken place at Le6n, although on a smaller scale, the camp of the Legio VI1 Gemina (Vidal 1986c; Miguel and Garcia 1993). A total of more than 50 building sites have been subject to archaeological investigation, ranging from simple watching briefs to more-frequent open-area excavations. In some cases the excavated remains have been preserved beneath newly constructed buildings and incorpor- ated into public spaces' (Figure 1). From all of this somewhat frenetic activity an enormous body of histori- cal information has been derived, which has still to be studied in depth? Nevertheless it allows a new picture to be presented of one of the least well-known of the towns of Roman Spain? Literary sources Asturica Augusta is mentioned in classical literature on a number of occasions. The earliest reference, cited at the beginning of this paper, is by Pliny the Elder (AD 23-79), procurator of the province of Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis at around AD 73, during the reign of the Emperor Vespasian. -

Roman-Barbarian Marriages in the Late Empire R.C

ROMAN-BARBARIAN MARRIAGES IN THE LATE EMPIRE R.C. Blockley In 1964 Rosario Soraci published a study of conubia between Romans and Germans from the fourth to the sixth century A.D.1 Although the title of the work might suggest that its concern was to be with such marriages through- out the period, in fact its aim was much more restricted. Beginning with a law issued by Valentinian I in 370 or 373 to the magister equitum Theodosius (C.Th. 3.14.1), which banned on pain of death all marriages between Roman pro- vincials and barbarae or gentiles, Soraci, after assessing the context and intent of the law, proceeded to discuss its influence upon the practices of the Germanic kingdoms which succeeded the Roman Empire in the West. The text of the law reads: Nulli provineialium, cuiuscumque ordinis aut loci fuerit, cum bar- bara sit uxore coniugium, nec ulli gentilium provinciales femina copuletur. Quod si quae inter provinciales atque gentiles adfinitates ex huiusmodi nuptiis extiterit, quod in his suspectum vel noxium detegitur, capitaliter expietur. This was regarded by Soraci not as a general banning law but rather as a lim- ited attempt, in the context of current hostilities with the Alamanni, to keep those barbarians serving the Empire (gentiles)isolated from the general Roman 2 populace. The German lawmakers, however, exemplified by Alaric in his 63 64 interpretatio,3 took it as a general banning law and applied it in this spir- it, so that it became the basis for the prohibition under the Germanic king- doms of intermarriage between Romans and Germans. -

Actas CONGRESO 7™ SESIO

XVIII CIAC: Centro y periferia en el Mundo Clásico / Centre and periphery in the ancient world S. 7. Las vías de comunicación en Grecia y Roma: rutas e infraestructuras Communication routes in Greece and Rome: routes and infrastructures Mérida. 2014: xxx-xxx HEADING WEST TO THE SEA FROM AUGUSTA EMERITA: ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD DATA AND THE ANTONINE ITINERARY Maria José de Almeida1, André Carneiro2 University of Lisbon1, University of Évora2 ABSTRACT The provincial capital of Lusitania plays a key role in the communications network of Hispania. The roads heading West were of great importance as they guaranteed a connection to the Atlantic Ocean and access to the maritime trade. The archaeological fieldwork that was undertaken in the region has enabled us to recognise direct and indirect evidence of these routes, presented here as a partial reconstitution of Lusitania’s road network. This cartography is confronted with the Antonine Itinerary description of these routes, highlighting numerous interpretation problems. The provincial capital of Roman Lusitania plays a unquestionably be identified with Santarém key role in the communications network of Hispania. (Portugal)6. The exact location of the remaining 14 Although its location on the major North-South route mansiones is still uncertain, despite ongoing and (Vía de la Plata) is well known and has been studied, vibrant discussions among scholars. the roads heading West were equally important, since Another interpretation problem is related to the they guaranteed a connection to the Atlantic Ocean figures for the total distance between the starting and and access to the maritime trade. The Antonine ending points and those that supposedly measure the Itinerary (AI)1 mentions three routes heading West distance of the intermediate points. -

USA OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753

11.12.2017 LISTE DES EXPORTATEURS ET IMPORTATEURS D’HUILES D’OLIVE, D’HUILES DE GRIGNONS D’OLIVE ET D’OLIVES DE TABLE LIST OF EXPORTERS AND IMPORTERS OF OLIVE OILS, OLIVE-POMACE OILS AND TABLE OLIVES UNITED STATES OF AMERICA/ÉTATS-UNIS D’AMÉRIQUE ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY NORTH AMERICAN OLIVE 3301 Route 66 – Suite 205, USA www.naooa.org OIL ASSOCIATION (NAOOA) Building C NEPTUNE NJ 07753 ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. SPAIN www.acesur.com 550,6 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla SPAIN s/n 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR Camino Alcoba, s/n SPAIN www.agolives.com S.L. 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN www.aceitunasmontegil.es 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 SPAIN 41510 MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, SPAIN S.A. 14 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. SPAIN www.acolsa.es S.A. IV Km. 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AEGEAN STAR FOOD Kral Incir Isletmesi TURKEY www.aegeanstar.com.tr INDUSTRY TRADE LTD. Dallica Mevkii 09800 NAZ AGRICOLA I CAIXA Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com AGRARIA SC CAMBRILS 43850 CAMBRILS SCCL (Tarragona) 2 ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE COUNTRY AGRITALIA S.R.L. -

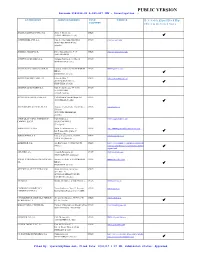

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation

PUBLIC VERSION Barcode:3583338-02 A-469-817 INV - Investigation - ENTITÉ/BODY ADRESSE/ADDRESS PAYS/ WEBSITE Believed to Export Black Ripe COUNTRY Olives to the United States ACEITES BORGES PONT, S.A. Avda. J. Trepat s/n SPAIN 25300 TARREGA (Lleida) ACEITES DEL SUR, S.A. Ctra. Sevilla-Cádiz, Km. 550,6 SPAIN www.acesur.com 41700 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) ACEITES TOLEDO S.A. Paseo Pintor Rosales, 4 y 6 SPAIN www.aceitestoledo.com 28008 MADRID ACEITUNAS DE MESA S.L. Antiguo Camino de Sevilla s/n SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS GUADALQUIVIR S.L. Camino Alcoba, s/n 41530 MORON SPAIN www.agolives.com DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS MONTEGIL, S.L. Eduardo Dato, 9 SPAIN http://www.montegil.es/ 41530 MORON DE LA FRONTERA (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS RUMARIN S.A. Calle Pedro Crespo, 79 41510 SPAIN MAIRENA DEL ALCOR (Sevilla) ACEITUNAS SEVILLANAS S.A. Calle Párroco Vicente Moya, 14 SPAIN 41840 PILAS (Sevilla) ACTIVIDADES OLEICOLAS, S.A. Autovia Sevilla-Cádiz, Ctra. IV Km. SPAIN www.acolsa.es 550-600 41703 DOS HERMANAS (Sevilla) AGRICOLA I CAIXA AGRARIA SC Calle Sindicat, 2 SPAIN www.coopcambrils.com CAMBRILS SCCL 43850 CAMBRILS (Tarragona) AGRO SEVILLA USA Avda. de la Innovación, s/n SPAIN http://www.agrosevilla.com/en/contact/ Ed. Rentasevilla, planta 8ª 41020 Sevilla AGRUCAPERS, S.A. Ctra. de Lorca, Km 3,2 30880 SPAIN www.agrucapers.es AGUILAS (Murcia) ALMINTER, S.A. Av. Río Segura, 9 30562 CEUTI SPAIN http://www.aliminter.com/index.php/produ (Murcia) ctos-nacional/bangor-encurtidos/aceitunas- negras.html AMANIDA SA Avenida Zaragoza, 83 SPAIN www.amanida.com 50630 ALAGON (Zaragoza) ANGEL CAMACHO ALIMENTACION, Avenida del Pilar, 6 41530 MORON SPAIN www.acamacho.com S.L. -

CONTINUITY and CHANGE in the EIGHTH CENTURY Conciliar

CHAPTER 6 CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THE EIGHTH CENTURY Conciliar Continuity: Alaric to Clovis In September 506, thirty-four Gallo-Roman clerics met in the city of Agde “with the permission of our most glorious, magnifi cent, and pious lord king.”1 Th e honored rex was Alaric II, an Arian Christian, who hoped that by authorizing a council of Catholic prelates, he would be able to rely on their loyalty in the ongoing fi ght for political domina- tion in Gaul.2 Alaric’s dream of a Visigothic-dominated Gaul would be crushed only a year later, when he was defeated and killed by Clovis at the Battle of Vouillé.3 But in 506, the king was still vigorously attempt- ing to hold together a unifi ed Visigothic realm. Th e same year that he convoked the Council of Agde, he also issued the Lex Romana Visig- othorum (or Breviarium), a compilation of Roman law whose infl uence would far outlive Alaric himself.4 Following Clovis’ victory, and the establishment of Merovingian dominance in Gaul, the Lex Romana Visigothorum continued to be copied and consulted frequently, even though manuscripts of the Codex Th eodosianus were still in circula- tion.5 For Alaric, however, the codifi cation project had a more imme- diate aim: uniting the Roman subjects of his kingdom under a single code of laws issued in his own name. Alaric’s unifi cation eff orts were 1 Agde (506), Preface. 2 Mathisen, “Th e Second Council of Arles,” 543, has suggested that Arles II (442/506) was convoked for the same reasons already postulated for the Council of Agde (506). -

Asturica Augusta

Today, as yesterday, communication and mobility are essential in the configuration of landscapes, understood as cultural creations. The dense networks of roads that nowadays crisscross Europe have a historical depth whose roots lie in its ancient roads. Under the might of Rome, a network of roads was designed for the first time that was capable of linking points very far apart and of organizing the lands they traversed. They represent some of the Empire’s landscapes and are testimony to the ways in which highly diverse regions were integrated under one single power: Integration Water and land: Integration Roads of conquest The rural world of the limits ports and trade of the mountains Roads of conquest The initial course of the roads was often marked by the Rome army in its advance. Their role as an instrument of control over conquered lands was a constant, with soldiers, orders, magistrates, embassies and emperors all moving along them. Alesia is undoubtedly one of the most emblematic landscapes of the war waged by Rome’s legions against the peoples that inhabited Europe. Its material remains and the famous account by Caesar, the Gallic Wars, have meant that Alesia has been recognized for two centuries now as a symbol of the expansion of Rome and the resistance of local communities. Alesia is the famous battle between Julius Caesar and Vercingetorix, the Roman army against the Gaulish tribes. The siege of Alesia took place in 52 BC, but its location was not actually discovered until the 19th century thanks to archeological research! Located on the site of the battle itself, in the centre of France, in Burgundy, in the village of Alise-Sainte-Reine, the MuseoParc Alesia opened its doors in 2012 in order to provide the key to understanding this historical event and the historical context, in order to make history accessible to the greatest number of people. -

Ordering Divine Knowledge in Late Roman Legal Discourse

Caroline Humfress ordering.3 More particularly, I will argue that the designation and arrangement of the title-rubrics within Book XVI of the Codex Theodosianus was intended to showcase a new, imperial and Theodosian, ordering of knowledge concerning matters human and divine. König and Whitmarsh’s 2007 edited volume, Ordering Knowledge in the Roman Empire is concerned primarily with the first three centuries of the Roman empire Ordering Divine Knowledge in and does not include any extended discussion of how knowledge was ordered and structured in Roman juristic or Imperial legal texts.4 Yet if we classify the Late Roman Legal Discourse Codex Theodosianus as a specialist form of Imperial prose literature, rather than Caroline Humfress classifying it initially as a ‘lawcode’, the text fits neatly within König and Whitmarsh’s description of their project: University of St Andrews Our principal interest is in texts that follow a broadly ‘compilatory’ aesthetic, accumulating information in often enormous bulk, in ways that may look unwieldy or purely functional In the celebrated words of the Severan jurist Ulpian – echoed three hundred years to modern eyes, but which in the ancient world clearly had a much higher prestige later in the opening passages of Justinian’s Institutes – knowledge of the law entails that modern criticism has allowed them. The prevalence of this mode of composition knowledge of matters both human and divine. This essay explores how relations in the Roman world is astonishing… It is sometimes hard to avoid the impression that between the human and divine were structured and ordered in the Imperial codex accumulation of knowledge is the driving force for all of Imperial prose literature.5 of Theodosius II (438 CE). -

The Self-Coronations of Iberian Kings: a Crooked Line

THE SELF-Coronations OF IBERIAN KINGS: A CROOKED LINE JAUME AURELL UNIVERSIDAD DE NAVARRA SpaIN Date of receipt: 10th of March, 2012 Final date of acceptance: 4th of March, 2014 ABSTRACT This article focuses on the practice of self-coronation among medieval Iberian Castilian kings and its religious, political, and ideological implications. The article takes Alfonso XI of Castile self-coronation (1332) as a central event, and establishes a conceptual genealogy, significance, and relevance of this self-coronation, taking Visigothic, Asturian, Leonese, and Castilian chronicles as a main source, and applying political theology as a methodology. The gesture of self-coronation has an evident transgressive connotation which deserves particular attention, and could throw some light upon the traditional debate on the supposed “un-sacred” kingship of Castilian kings1. KEY WORDS Coronation, Unction, Castile, Monarchy, Political Theology. CAPITALIA VERBA Coronatio, Unctio, Castella, Monarchia, Theologia politica. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, VIII (2014) 151-175. ISSN 1888-3931 151 152 JAUME AURELL 1Historians have always been fascinated by the quest for origins. Alfonso XI of Castile and Peter IV of Aragon’s peculiar and transgressive gestures of self-coronation in the fourteenth century are very familiar to us, narrated in detail as they are in their respective chronicles2. Yet, their ritual transgression makes us wonder why they acted in this way, whether there were any precedents for this particular gesture, and to what extent they were aware of the different rates at which the anointing and coronation ceremonies were introduced into their own kingdoms, in their search for justification of the self-coronation3. -

Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages

Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages by Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler 2018 Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages Nicholas Brett Sivulka Wheeler Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation, ‘Perjury and False Witness in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages’, investigates changing perceptions of perjury and false witness in the late antique and early medieval world. Focusing on primary sources from the Latin-speaking, western Roman empire and former empire, approximately between the late third and seventh centuries CE, this thesis proposes that perjury and false witness were transformed into criminal behaviours, grave sins, and canonical offences in Latin legal and religious writings of the period. Chapter 1, ‘Introduction: The Problem of Perjury’s Criminalization’, calls attention to anomalies in the history and historiography of the oath. Although the oath has been well studied, oath violations have not; moreover, important sources for medieval culture – Roman law and the Christian New Testament – were largely silent on the subject of perjury. For classicists in particular, perjury was not a crime, while oath violations remained largely peripheral to early Christian ethical discussions. Chapter 2, ‘Criminalization: Perjury and False Witness in Late Roman Law’, begins to explain how this situation changed by documenting early possible instances of penalization for perjury. Diverse sources such as Christian martyr acts, provincial law manuals, and select imperial ii and post-imperial legislation suggest that numerous cases of perjury were criminalized in practice. -

The Edictum Theoderici: a Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy

The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy By Sean D.W. Lafferty A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Sean D.W. Lafferty 2010 The Edictum Theoderici: A Study of a Roman Legal Document from Ostrogothic Italy Sean D.W. Lafferty Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This is a study of a Roman legal document of unknown date and debated origin conventionally known as the Edictum Theoderici (ET). Comprised of 154 edicta, or provisions, in addition to a prologue and epilogue, the ET is a significant but largely overlooked document for understanding the institutions of Roman law, legal administration and society in the West from the fourth to early sixth century. The purpose is to situate the text within its proper historical and legal context, to understand better the processes involved in the creation of new law in the post-Roman world, as well as to appreciate how the various social, political and cultural changes associated with the end of the classical world and the beginning of the Middle Ages manifested themselves in the domain of Roman law. It is argued here that the ET was produced by a group of unknown Roman jurisprudents working under the instructions of the Ostrogothic king Theoderic the Great (493-526), and was intended as a guide for settling disputes between the Roman and Ostrogothic inhabitants of Italy. A study of its contents in relation to earlier Roman law and legal custom preserved in imperial decrees and juristic commentaries offers a revealing glimpse into how, and to what extent, Roman law survived and evolved in Italy following the decline and eventual collapse of imperial authority in the region.