Geological Conservation a Guide to Good Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decision Document: Tilbury Green Power Limited

Determination of an Application for an Environmental Permit under the Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2010 Decision document recording our decision-making process The Application Number is: EPR/KP3936ZB/A001 The Applicant is: Tilbury Green Power Limited The Installation is located at: Tilbury Dock, Essex What this document is about This is a decision document, which accompanies a permit. It explains how we have considered the Applicant’s Application, and why we have included the specific conditions in the permit we are issuing to the Applicant. It is our record of our decision-making process, to show how we have taken into account all relevant factors in reaching our position. Unless the document explains otherwise, we have accepted the Applicant’s proposals. We try to explain our decision as accurately, comprehensively and plainly as possible. Achieving all three objectives is not always easy, and we would welcome any feedback as to how we might improve our decision documents in future. A lot of technical terms and acronyms are inevitable in a document of this nature: we provide a glossary of acronyms near the front of the document, for ease of reference. Preliminary information and use of terms We gave the application the reference number EPR/KP3936ZB/A001. We refer to the application as “the Application” in this document in order to be consistent. The number we have given to the permit is EPR/KP3936ZB. We refer to the permit as “the Permit” in this document. The Application was duly made on 21 November 2013. The Applicant is Tilbury Green Power Limited. -

Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility Phase 2 Development SECTION

Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility Phase 2 Development SECTION 36C VARIATION SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT December 2018 Version control Issue Revision No. Date Issued Description of Description of Reviewed by: Revision: Revision: Page No. Comment 001 00 01/11/18 All Prelim draft to PN agree structure 001 01 09/11/18 All Draft for client PN review 001 02 28/11/18 All Draft for PN submission 001 03 11/12/18 All Final PN Issue Revision No. Date Issued Description of Revision: Page This report dated Dec 2018 has been prepared for Tilbury Green Power Ltd (the “Client”) in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment (the “Appointment”) for the purposes specified in the Appointment. For avoidance of doubt, no other person(s) may use or rely upon this report or its contents, and no responsibility is accepted for any such use or reliance thereon by any other third party. Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility SECTION 36C VARIATION SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Overview ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 The Proposed Changes .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Purpose of this Document -

Internal Draft Version June 2006)

(Internal Draft Version June 2006) THURROCK LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (LDF) SITE SPECIFIC ALLOCATIONS AND POLICIES “ISSUES AND OPTIONS” DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT [DPD] INFORMAL CONSULTATION DRAFT CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. STRATEGIC & POLICY CONTEXT 4 3. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BOROUGH 6 4. KEY PRINCIPLES 7 5. RELATIONSHIP WITH CORE STRATEGY VISION, 7 OBJECTIVES & ISSUES 6. SITE SPECIFIC PROVISIONS 8 7. MONITORING & IMPLEMENTATION 19 8. NEXT STEPS 19 APPENDICES 20 GLOSSARY OF TERMS REFERENCE LIST INTERNAL DRAFT VERSION JUNE 2006 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We would like to get your views on future development and planning of Thurrock to 2021. A new system of “Spatial Planning” has been introduced that goes beyond traditional land-use planning and seeks to integrate the various uses of land with the various activities that people use land for. The new spatial plans must involve wider community consultation and involvement and be based on principles of sustainable development. 1.2 The main over-arching document within the LDF portfolio is the Core Strategy. This sets out the vision, objectives and strategy for the development of the whole area of the borough. The Site Specific Allocations and Policies is very important as it underpins the delivery of the Core Strategy. It enables the public to be consulted on the various specific site proposals that will guide development in accordance with the Core Strategy. 1.3 Many policies in the plans will be implemented through the day-to-day control of development through consideration of planning applications. This document also looks at the range of such Development Control policies that might be needed. -

Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ART and SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A comparative study. by Hannah Louise Fluck Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 1 2 Abstract This thesis presents the results of an investigation into the Clactonian assemblages of Middle Pleistocene souther Britain. By exploring other non-biface assemblages (NBAs) reported from elsewhere in Europe it seeks to illuminate our understanding of the British assemblages by viewing them in a wider context. It sets out how the historical and geopolitical context of Palaeolithic research has influenced what is investigated and how, as well as interpretations of assemblages without handaxes. A comparative study of the assemblages themselves based upon primary data gathered specifically for that purpose concludes that while there are a number of non-biface assemblages elsewhere in Europe the Clactonian assemblages do appear to be a phenomenon unique to the Thames Valley in early MIS 11. -

English Nature Research Report

Vatural Area: 33. East Anglian Plain Geological Sigaificance: Outstanding (provisional) General geological character: The solid geology of the East Anglian Natural Area is mainly underlain by Jpper Cretaceous chalk. This very pure limestone was laid down on the floor of a tropical sea between 97 md 74 Ma. Locally the chalk is rich in fossils including sea-urchins and bivalves. Overlying much of the ;halk is a complex sequence of Quaternary deposits (deposited over the last 2 Ma) showing changes in Aimate and environment from both cold (glacial) and temperate (interglacial) periods. These sediments hostcompletely obscure the underlying chalk and it is their composition which gives the Natural Area its :haacter. The base of the Quaternary sequence is the early Pleistocene Crag deposits which are marine jcdiments of*shelly muds and sands, often containing temperate marinc molluscan faunas. However, the nost extensive and thickest Quaternary sediments consist of glacial sands, gravels and clays deposited by the 4nglian ice sheet as it advanced across the area around 300,000 to 250,000 years BP. These deposits are ;ollectivcly known as 'boulder clay' and their calcareous nature reflects glacial erosion and transportation of he chalk bedrock beneath. The Anglian glaciation interrupted a well-developed fluvial network of eastward flowing rivers, and patches of these preglacial river gravels are still found within the area. Many localitites show river gravels related to the early development of the River Thames, which crossed this area prior to jiversion by the Anglian ice sheet. These sites are important for Quaternary stratigraphy (including records Jf climate change) because they can be correlated with sedirnents in other parts of Britain and abroad. -

Mark B. Roberts 10 the Earliest Ciive S Gamble the British Isles Occupation

Mark B. Roberts 10 The earliest occupation of Europe: ciive s Gamble the British Isles David R. Bridgland The evidence presented here suggests that the British This division is not based on any shift, real or perceived, in Isles wasfirst colonized at the heginning of the temperate hominid material culture nor on any concept of hominid or interglacial stage that immediately pre-dates the Anglian species change; rather it reflects the large scale changes to cold Stage. Lithostratigraphic and chronostratigraphic the palaeogeography and mammalian fauna composition of mode Hing correlates the Anglian with Oxygen Isotope Britain, that occurred as the result of physical and climatic Stage 12. which is dated to between 478. and 423 Kyr BP. factors relating to this glacial/cold event. The fixing in time Accordingly, the earliest occupation ofBritain occurred of the Anglian Stage has not yet been unequivocally agreed around half a million years ago. The early colonizers are upon by British Quaternary scientists but the weight of assigned, front the Boxgrove specimen, to the species Homo evidence suggests correlation with Oxygen Isotope Stage cf heidelbergensis. One hundred thousand years later, at (OIS) 12 (see below and Table 1). The model presented Swanscombe, this group hegins to exhibit some cranial here, although it fits with this hypothesis, is free-standing skeletal characteristics usually assoeiated with the and allows for future fine tuning of the geochronological Neanderthal lineage. Throughout the period covered by this timescale. pa/ter l/icrc is apparent stasis in the lithic industries, which On the evidence currently available to Quaternary include both biface dominant assemblages andflake tooi scientists, it is thought that the first hominids arrived in dominant assemblages. -

The Archaeological Potential of Secondary Contexts (ALSF Project 3361) Dr Robert Hosfield & Jenni Chambers

The Archaeological Potential of Secondary Contexts (ALSF Project 3361) Dr Robert Hosfield & Jenni Chambers Interim Report Date: 28/08/03 Module: Characterisation of the potential of the secondary context geoarchaeological resource for the reconstruction of riverine palaeo- environments (Module 7) Goals: To assess the potential of biological data from archaeological secondary contexts for the reconstruction of Middle Pleistocene river palaeo-environments and landscapes. The assessment emphasises: • The identification of biological data sources with potential for reconstructing riverine palaeo-environments. • The relative potential of the different data sources, based on the frequency of their occurrence within the geoarchaeological record and the logistics of sampling and sample processing. • The spatio-temporal resolution of the different biological data sources, mapped against different scales of hominid behaviour. • Relationships between palaeo-environmental data and the current questions prevalent in studies of Pleistocene hominids. 1. Introduction This report assesses the potential for the palaeoenvironmental reconstruction of Middle Pleistocene fluvial landscapes from secondary context data sets. The main categories of biological data are identified and their potential applications highlighted. The key element however concerns the spatio-temporal resolution of these data sets and the mapping of these data sets against the varying scales of early human behaviour in time (e.g. an afternoon’s knapping activity, a seasonal settlement, or ten generations of sustained occupation) and space (e.g. throughout regional river systems, around a river estuary, or within the micro- environment of a floodplain backwater). This highlights the fundamental question of whether palaeoenvironmental reconstructions are relevant to the discussion of hominid behaviour or whether spatio-temporal associations between these data sets (biological and 1 ‘archaeological’ ) simply cannot be demonstrated for secondary contexts. -

Local Flood Risk Management Strategy, Appendix D2

Thurrock Local Flood Risk Management Strategy – Strategic Environmental Assessment Scoping Report March 2015 Thurrock Council Civic Offices New Road Grays Essex RM17 6SL JBA Project Manager Claire Gardner JBA Consulting The Library St Philips Courtyard COLESHILL Warwickshire B46 3AD RH16 4NG Revision history Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to Draft v0-2 / March 2015 Claire Gardner Final Thurrock Council Environment Agency Natural England English Heritage Contract This report describes work commissioned by Thurrock Council. Rachel Drabble and Laura Thomas of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by Rachel Drabble BSc (Hons) Environmental Consultant Reviewed by Laura Thomas BA MRes MCIEEM Senior Ecologist Purpose This document has been prepared as a SEA Scoping Report for Thurrock Council. JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document other than by the Client for the purposes for which it was originally commissioned and prepared. JBA Consulting has no liability regarding the use of this report except to Thurrock Council. 2014s1942 Thurrock LFRMS SEA Scoping Report v1.0.docx i Copyright © Jeremy Benn Associates Limited 2015 Carbon footprint A printed copy of the main text in this document will result in a carbon footprint of 223g if 100% post-consumer recycled paper is used and 283g if primary-source paper is used. These figures assume the report is printed in black and white on A4 paper and in duplex. JBA is aiming to reduce its per capita carbon emissions. 2014s1942 Thurrock LFRMS SEA Scoping Report v1.0.docx ii Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 The Local Flood Risk Management Strategy .............................................................. -

Thurrock Council As Part of the Development of Its Greengrid Strategy

Appendix 1.2.13. INDEX 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 General Introduction 1 1.2 Background 3 2. OVERVIEW OF THURROCK 2.1 Recent Changes 5 2.2 Other Changes, Opportunities and Issues 6 2.3 BAP Resources Within Thurrock 6 2.3.1 Habitats 7 2.3.2 Species 14 2.3.3 Other BAP Issues 18 2.3.4 Summary of BAP Action Points 19 2.4 The Role of Local Wildlife Sites 20 2.5 Discussion of Local Wildlife Sites 21 2.6 Introduction to Wildlife Corridors 22 2.6.1 Corridor Requirements 23 2.6.2 Wildlife Corridors in Thurrock 26 2.6.3 Planning for the Future 28 References and Selected Bibliography Glossary of Abbreviations MAP1 Primary Corridors/Barriers Appendix 1 Development of Local Wildlife Site Selection Criteria In Essex Appendix 2 Species Indicative of Ancient Woodland In Essex Appendix 3 Species Indicative of Old, Unimproved Neutral/Acid Grassland and Marsh In Essex Appendix 4 Indicative Chalk Grassland Plants Appendix 5 Evolution of Local Nature Conservation Initiatives Appendix 6 Local Wildlife Sites Register Appendix 7 Tables and Maps of Potential Local Wildlife Sites Appendix 8 A Review Of Thurrock SSSIs Within The Local Wildlife Site Framework GREENGRID WILDLIFE STRATEGY FOR THURROCK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 General Introduction Lying at the centre of the Thames Gateway, Thurrock is a key growth area that is set to undergo significant change. The next 15 years will see large numbers of additional houses plus development for employment. The protection and enhancement of those elements of the environment which give Thurrock its positive identity, including its ecological character, will be a critical aspect of the Greengrid and will influence the views of those who live and work in the area, as well as those passing through or considering investing. -

Greater Thames Research Framework 2010

THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 2010 Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary (1999) THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary (1999) June 2010 Prepared by Essex County Council, Historic Environment Branch On the behalf of Greater Thames Estuary Archaeological Steering Committee THE GREATER THAMES ESTUARY HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH FRAMEWORK Update and Revision of the Archaeological Research Framework for the Greater Thames Estuary’ (1999) Project Title: Greater Thames Estuary Research Framework Review English Heritage Proj. Ref: 5084 ECC Proj. Ref: 1592 Prepared by: E M Heppell (EMH) Project Officer, Essex County Council Field Archaeology Unit Fairfield Court Fairfield Road Braintree CM7 3YQ e-mail: [email protected] Tel: 01376 331431 Derivation: 1592GTRF_draft_feb10 Origination Date: July 2009 Date of document: Nov 2010 Version: 6 Status: Final document Summary of changes: Final report Circulation: General circulation Filename and location: ECC FAU, Braintree H:/fieldag/project/1592/text/1592GRRF_Final_Nov10.doc CONTENTS PART 1 FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 THE DEVELOPMENT AND PALAEOENVIRONMENT OF THE THAMES ESTUARY 2.1 The Thames through Time 2.2 Palaeolithic and Mesolithic 2.3 Relative Sea-level 2.4 Recent Projects Lower Palaeolithic (pre-425 kBP; MIS 12 and earlier) Lower to Middle Palaeolithic (415–125 -

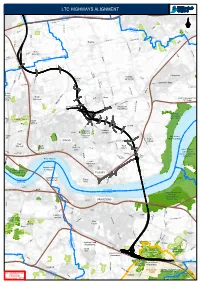

Ltc Highways Alignment Whole Route

LTC HIGHWAYS ALIGNMENT Brentwood B1036 Havering Shoeburyness Railway Brentwood Thurrock St Mary's Lane Basildon B1007 Thurrock A176 B1464 B187 Lane Dunnings Dry Street B186 Old Church Hill Doesgate Lane Bulphan Lower Dunton Road A13 Pike Lane B1007 High Road North B1420 B1421 Ockendon Fen Lane B1421 A128 Pea Lane Havering Ockendon Road Thurrock CH17+500 CH20+000 CH18+000 CH19+000 CH17+000 Upminster and Grays CH18+500 CH19+500 Farm Road CH16+500 Parker's Corringham Branch B1007 CH16+000 Horndon Dennis Road Orsett Conway's Road on the Hill Fen B188 North Road CH15+500 Stanford-le-Hope M25 A1014 West Road Brentwood Road Saffron Gardens The Manorway CH15+000 Belhus A1013 Woods South CH14+500 Baker Street Country Orsett London Gateway Port Ockendon B188 Park Rectory Road (DP World) Butts Lane CH14+000 Mardyke River A13 Stanford Road Stifford Clays Road CH13+500 Orsett Cock Roundabout CH13+000 Bukingham Hill Road A1013 Thurrock CH12+500 Thameside CH12+000 Nature Park M25 Mardyke Valley J30 North CH11+500 A13 Stifford B188 Linford CH11+000 CH10+500 Ship Lane A1013 Chadwell A1306 Hangman's A1306 St Mary Princess Margaret Road CH9+500 Wood and A1089 CH10+000 A126 A1012 Denehole's A282 The Greater J31 SSSI CH9+000 East Thames Estuary GRAYS Muckingford Road B149 Turnpike Lane Tilbury Linford Road West CH8+500 Thurrock South West Stifford Globe Pit A126 Tilbury SSSI South Thames A1090 CH8+000 Estuary and London Road London Tilbury Southend (LTS) Church Road Railway Marshes, SSSI and Coopers Shaw Station Road Ramsar Site A1089 Road River Thames CH7+500 -

WA/91/28 SW Essex

BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY TECHNICAL REPORTWN91/28 Onshore Geology Series South-west Essex-M25 corridor Applied geology for planning and development B S P Moorlock and A Smith Cover illustration Mapoftheareacoveredby Contributors the survey M D A Samuel Database Geographical index M G Culshaw Engineering geology United Kingdom, south- east England, Essex M A Lewis Hydrogeology Subject index Geology, hydrogeology, engineering geology, stratigraphy, Mesozoic, Tertiary, Quaternary, minerals, land-use planning The views expressed in this report do not necessarily coincide with thoseof the Department of the Environment Maps and diagramsin this report use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping Bibliographic reference MOORLOCK,B S P, and SMITH,A. 1991. South- west Essex-M25 corridor: applied geology forplanning anddevelopment. British Geological Survey Technical Report WN9lI28. @ Crown amwight 1991 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 1991 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available through the Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Keyworth and at Murchison House, Edinburgh, = 0602-363100Telex 378173 BGSKEY G and in theBGS London Information Office in the Natural Fax 0602-363200 History Museum Earth Galleries. The adjacent bookshop stocks the more popular books for sale over the counter. MostBGS Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH93LA books and reports are listed in HMSO’s Sectional List 45, and 031-667 1000 Telex 727343 SEISED G can be bought from HMSO and through HMSO agents