Essex LGAP 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Essex Field Club

THE ESSEX FIELD CLUB DEPARTMENT OF LIFE SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF EAST LONDON ROMFORD ROAD, STRATFORD, LONDON, E15 4LZ NEWSLETTER NO. 16 February 1996 FROM THE PRESIDENT How would you describe the aims and activities of the present day Essex Field Club? When the Club first came into being it might not have been that inappropriate to regard its activities as encompassing ‘hunting, shooting and fishing’, the collection of dead voucher specimens of everything living in Essex being one of the Club’s primary objectives. Today however, our members would regard themselves as anything but, members of an organization that might be misconstrued as indulging in ‘field sports’ . Our Club is surely primarily a natural history society, with a present-day emphasis an recording, conservatian and natural history education. Your Council had a special meeting on the 31 January to look at the present and potential future role of the EFC in Essex, debating just how we could give the Club a new attractive image that would give us a steadily increasing membership, and how best we might interrelate to such organisations as the Essex Wildlife Trust, English Nature, the National Biological Records Centre and the local county natural history societies. Particularly in view of our proposed partnership in a new museum on Epping Forest. As a result of this meeting Council will be proposing at the next AGM that the Club should change its name to the ESSEX NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY, and redefine its objectives, and rules, in line with its modern image. We propose subtitling the new name with ‘formerly the Essex Field Club’ for a few years, and retention of our ‘speckled wood on blackberry leaf logo’ , to give us continuity. -

Decision Document: Tilbury Green Power Limited

Determination of an Application for an Environmental Permit under the Environmental Permitting (England & Wales) Regulations 2010 Decision document recording our decision-making process The Application Number is: EPR/KP3936ZB/A001 The Applicant is: Tilbury Green Power Limited The Installation is located at: Tilbury Dock, Essex What this document is about This is a decision document, which accompanies a permit. It explains how we have considered the Applicant’s Application, and why we have included the specific conditions in the permit we are issuing to the Applicant. It is our record of our decision-making process, to show how we have taken into account all relevant factors in reaching our position. Unless the document explains otherwise, we have accepted the Applicant’s proposals. We try to explain our decision as accurately, comprehensively and plainly as possible. Achieving all three objectives is not always easy, and we would welcome any feedback as to how we might improve our decision documents in future. A lot of technical terms and acronyms are inevitable in a document of this nature: we provide a glossary of acronyms near the front of the document, for ease of reference. Preliminary information and use of terms We gave the application the reference number EPR/KP3936ZB/A001. We refer to the application as “the Application” in this document in order to be consistent. The number we have given to the permit is EPR/KP3936ZB. We refer to the permit as “the Permit” in this document. The Application was duly made on 21 November 2013. The Applicant is Tilbury Green Power Limited. -

Geological Conservation a Guide to Good Practice

Geological conservation a guide to good practice working towards Natural England for people, places and nature Roche Rock, Cornwall. Mick Murphy/English Nature Contents Foreword 4 1 Why conserve geology? 7 1.1 What are geology and geomorphology? 7 1.2 Why is geology important? 7 1.3 Why conserve geological features? 10 1.4 Who benefits from geological conservation? 13 2 Geological site conservation 15 2.1 Introduction 15 2.2 Site audit and selection 15 2.3 Legislation and site designation 19 2.4 Site safeguard and management 20 2.4.1 The Earth Science Conservation Classification (ESCC) 20 2.4.2 Site safeguard and threat deflection 26 2.4.3 Site management 29 2.4.3.1 Site management plans and conservation 30 objectives 2.4.3.2 Site monitoring 31 2.4.3.3 Physical maintenance of sites 32 2.4.3.4 Management aimed at threat deflection 34 2.4.3.5 Site interpretation 35 3 Management guidance by site type 37 3.1 Active quarries and pits EA 38 3.2 Disused quarries and pits ED 39 3.3 Coastal cliffs and foreshore EC 47 3.4 River and stream sections EW 49 3.5 Inland outcrops EO 51 3.6 Exposure underground mines and tunnels EU 52 3.7 Extensive buried interest EB 53 3.8 Road, rail and canal cuttings ER 55 3.9 Static (fossil) geomorphological IS 58 3.10 Active process geomorphological IA 60 3.11 Caves IC 62 3.12 Karst IK 64 3.13 Finite mineral, fossil or other geological FM 65 3.14 Mine dumps FD 66 3.15 Finite underground mines and tunnels FU 68 3.16 Finite buried interest FB 69 Geological conservation: a guide to good practice By: Colin Prosser, Michael Murphy and Jonathan Larwood Drawn in part from work undertaken for English Nature by Capita Symonds (Jane Poole and David Flavin). -

16 August 2018 Our Ref: 244199 Basildon Borough

Date: 16 August 2018 Our ref: 244199 Basildon Borough Council Braintree District Council Customer Services Brentwood Borough Council Hornbeam House Castle Point Borough Council Crewe Business Park Electra Way Chelmsford Borough Council Crewe Colchester Borough Council Cheshire Maldon District Council CW1 6GJ Rochford District Council Southend-on-Sea Borough Council T 0300 060 3900 Tendring District Council Thurrock Borough Council Uttlesford District Council Essex Place Services BY EMAIL ONLY Dear All Emerging strategic approach relating to the Essex Coast Recreational disturbance Avoidance and Mitigation Strategy (RAMS) – Revised interim advice to ensure new residential development and any associated recreational disturbance impacts on European designated sites are compliant with the Habitats Regulations1 This letter provides Natural England’s revised interim advice further to that issued on 16th November 2017. This advice is provided to ensure that any residential planning applications coming forward ahead of the Essex Coast RAMS which have the potential to impact on coastal European designated sites are compliant with the Habitats Regulations. It specifically relates to additional recreational impacts that may occur on the interest features of the following European designated sites: Essex Estuaries Special Area of Conservation (SAC) Hamford Water Special Protection Area (SPA) and Ramsar site2 Stour and Orwell Estuaries SPA and Ramsar site (Stour on the Essex side only) Colne Estuary SPA and Ramsar site Blackwater Estuary SPA and Ramsar site Dengie SPA and Ramsar site Crouch and Roach Estuaries SPA and Ramsar site Foulness Estuary SPA and Ramsar site Benfleet and Southend Marshes SPA and Ramsar site Thames Estuary and Marshes SPA and Ramsar site (Essex side only) 1 Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, as amended (commonly known as the ‘Habitats Regulations’) 2 Listed or proposed Wetlands of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention (Ramsar) sites are protected as a matter of Government policy. -

Biodiversity, Habitats, Flora and Fauna

1 North East inshore Biodiversity, Habitats, Flora and Fauna - Protected Sites and Species 2 North East offshore 3 East Inshore Baseline/issues: North West Plan Areas 10 11 Baseline/issues: North East Plan Areas 1 2 4 East Offshore (Please note that the figures in brackets refer to the SA scoping database. This is • SACs: There are two SACs in the plan area – the Berwickshire and North available on the MMO website) Northumberland Coast SAC, and the Flamborough Head SAC (Biodiv_334) 5 South East inshore • Special Areas of Conservation (SACs): There are five SACs in the plan area • The Southern North Sea pSAC for harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) 6 South inshore – Solway Firth SAC, Drigg Coast SAC, Morecambe Bay SAC, Shell Flat and is currently undergoing public consultation (until 3 May 2016). Part of Lune Deep SAC and Dee Estuary SAC (Biodiv_372). The Sefton Coast the pSAC is in the offshore plan area. The pSAC stretches across the 7 South offshore SAC is a terrestrial site, mainly for designated for dune features. Although North East offshore, East inshore and offshore and South East plan areas not within the inshore marine plan area, the development of the marine plan (Biodiv_595) 8 South West inshore could affect the SAC (Biodiv_665) • SPAs: There are six SPAs in the plan area - Teesmouth and Cleveland 9 South west offshore • Special protection Areas (SPAs): There are eight SPAs in the plan area - Coast SPA, Coquet Island SPA, Lindisfarne SPA, St Abbs Head to Fast Dee Estuary SPA, Liverpool Bay SPA, Mersey Estuary SPA, Ribble and Castle SPA and the Farne Islands SPA, Flamborough Head and Bempton 10 North West inshore Alt Estuaries SPA, Mersey Narrows and North Wirral Foreshore SPA, Cliffs SPA (Biodiv_335) Morecambe Bay SPA, Duddon Estuary SPA and Upper Solway Flats and • The Northumberland Marine pSPA is currently undergoing public 11 North West offshore Marshes SPA (Biodiv_371) consultation (until 21 April 2016). -

Eight Ash Green Neighbourhood Plan Appropriate Assessment Report

1 Eight Ash Green Neighbourhood Plan Appropriate Assessment Report January 2019 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 Pathways of impact and likely significant effects ........................................................ 5 Recreational disturbance (physical site disturbance and disturbance to birds) .......... 5 Air quality ................................................................................................................... 5 Water quality .............................................................................................................. 6 Water resources ......................................................................................................... 7 Urbanisation (fly tipping and predation) ...................................................................... 7 Appropriate assessment: likely significant effects alone ............................................. 9 Appropriate assessment: likely significant effects in-combination ............................ 10 Appendix 1. Screening Matrix of Eight Ash Green Neighbourhood Plan policies ..... 12 Appendix 2: Information about Habitats sites ........................................................... 14 3 Introduction The Habitats Regulations Assessment of land use plans relates to Special Protection Areas (SPAs), Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Ramsar Sites. SPAs are sites classified in accordance with Article 4 of the EC Directive on the conservation -

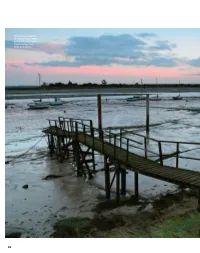

Blackwater Estuary in Essex at Low Tide, Where Yachts Tilt on the Tidal Mud and Migrating Birds Overwinter

Blackwater estuary in Essex at low tide, where yachts tilt on the tidal mud and migrating birds overwinter 68 ESCAPE | OUTING Where the river meets the sea ESTUARIES ARE AT THEIR MOST POETIC AT THIS TIME OF YEAR. WANDER THERE FOR A LITTLE BROODING AND BIRD WATCHING Words: CLARE GOGERTY here are times when the landscape suits, even amplifies, your mood. A sandy beach on a sunny summer’s day buoys feelings of jollity. A mountain top uplifts and Texhilarates as you fill your lungs and look at the never-ending view. But where do you go when you want to indulge a reflective mood? When you want some time alone, perhaps, to think a little? To wander and wonder? I always head to an estuary – the Blackwater estuary between Maldon and West Mersea in Essex in particular – and especially round about now when it is at its most evocative and mysterious. An estuary is the tidal mouth of a big river, a shifting ALAMY landscape where the river and the sea meet. It reveals itself quietly: on a chilly winter morning, it is threaded with mist and the PHOTOGRAPHY: PHOTOGRAPHY: only sounds a muffled foghorn from a » 69 ESCAPE | OUTING 1 Estuary legends Three spectral creatures who have arisen from the mists of an estuary 1. The Mermaid of Padstow, Camel estuary, Cornwall Out hunting for seals, local man Tristram Bird came across a beautiful maiden and fell in love, legend has it. Some say she tried to lure him under the sea, others that she rejected his marriage proposal. -

Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility Phase 2 Development SECTION

Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility Phase 2 Development SECTION 36C VARIATION SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT December 2018 Version control Issue Revision No. Date Issued Description of Description of Reviewed by: Revision: Revision: Page No. Comment 001 00 01/11/18 All Prelim draft to PN agree structure 001 01 09/11/18 All Draft for client PN review 001 02 28/11/18 All Draft for PN submission 001 03 11/12/18 All Final PN Issue Revision No. Date Issued Description of Revision: Page This report dated Dec 2018 has been prepared for Tilbury Green Power Ltd (the “Client”) in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment (the “Appointment”) for the purposes specified in the Appointment. For avoidance of doubt, no other person(s) may use or rely upon this report or its contents, and no responsibility is accepted for any such use or reliance thereon by any other third party. Tilbury Energy Recovery Facility SECTION 36C VARIATION SUPPLEMENTARY ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION REPORT Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Overview ................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 The Proposed Changes .......................................................................................... 2 1.4 Purpose of this Document -

Internal Draft Version June 2006)

(Internal Draft Version June 2006) THURROCK LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (LDF) SITE SPECIFIC ALLOCATIONS AND POLICIES “ISSUES AND OPTIONS” DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT [DPD] INFORMAL CONSULTATION DRAFT CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. STRATEGIC & POLICY CONTEXT 4 3. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BOROUGH 6 4. KEY PRINCIPLES 7 5. RELATIONSHIP WITH CORE STRATEGY VISION, 7 OBJECTIVES & ISSUES 6. SITE SPECIFIC PROVISIONS 8 7. MONITORING & IMPLEMENTATION 19 8. NEXT STEPS 19 APPENDICES 20 GLOSSARY OF TERMS REFERENCE LIST INTERNAL DRAFT VERSION JUNE 2006 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We would like to get your views on future development and planning of Thurrock to 2021. A new system of “Spatial Planning” has been introduced that goes beyond traditional land-use planning and seeks to integrate the various uses of land with the various activities that people use land for. The new spatial plans must involve wider community consultation and involvement and be based on principles of sustainable development. 1.2 The main over-arching document within the LDF portfolio is the Core Strategy. This sets out the vision, objectives and strategy for the development of the whole area of the borough. The Site Specific Allocations and Policies is very important as it underpins the delivery of the Core Strategy. It enables the public to be consulted on the various specific site proposals that will guide development in accordance with the Core Strategy. 1.3 Many policies in the plans will be implemented through the day-to-day control of development through consideration of planning applications. This document also looks at the range of such Development Control policies that might be needed. -

Estimating Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax Carbo Population Change As an Aid to Management

BTO Research Report No. 406 Estimating Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Population Change as an Aid to Management Authors S. M. Baylis, G. E. Austin, A. J. Musgrove & M. M. Rehfisch June 2005 Report of work carried out by The British Trust for Ornithology under contract to DEFRA British Trust for Ornithology The National Centre for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU Registered Charity No. 216652 British Trust for Ornithology Estimating Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Population Change as an Aid to Managment BTO Research Report No. 406 S.M. Baylis, G.E. Austin, A.J. Musgrove & M.M. Rehfisch Published in June 2005 by the British Trust for Ornithology The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk, IP24 2PU, UK Copyright British Trust for Ornithology 2005 ISBN 1-904870-49-X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Appendices ................................................................................................................................................. -

Site Improvement Plan Essex Estuaries

Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 Sites (IPENS) Planning for the Future Site Improvement Plan Essex Estuaries Site Improvement Plans (SIPs) have been developed for each Natura 2000 site in England as part of the Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 sites (IPENS). Natura 2000 sites is the combined term for sites designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protected Areas (SPA). This work has been financially supported by LIFE, a financial instrument of the European Community. The plan provides a high level overview of the issues (both current and predicted) affecting the condition of the Natura 2000 features on the site(s) and outlines the priority measures required to improve the condition of the features. It does not cover issues where remedial actions are already in place or ongoing management activities which are required for maintenance. The SIP consists of three parts: a Summary table, which sets out the priority Issues and Measures; a detailed Actions table, which sets out who needs to do what, when and how much it is estimated to cost; and a set of tables containing contextual information and links. Once this current programme ends, it is anticipated that Natural England and others, working with landowners and managers, will all play a role in delivering the priority measures to improve the condition of the features on these sites. The SIPs are based on Natural England's current evidence and knowledge. The SIPs are not legal documents, they are live documents that will be updated to reflect changes in our evidence/knowledge and as actions get underway. -

Maldon to Salcott Sensitive Features Report

Access and Sensitive Features Appraisal Coastal Access Programme This document records the conclusions of Natural England’s appraisal of any potential for ecological impacts from our proposals to establish the England Coast Path in the light of the requirements of the legislation affecting Natura 2000 sites, SSSIs, NNRs, protected species and Marine Conservation Zones. Maldon to Salcott (Blackwater Estuary) 30 March 2017 Contents 1. Our approach ............................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Scope ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Baseline conditions and ecological sensitivities ...................................................................................... 14 4. Potential for interaction .......................................................................................................................... 24 5. Assessment of any possible adverse impacts and mitigation measures ................................................. 27 6. Establishing and maintaining the England Coast Path ............................................................................ 34 7. Conclusions .............................................................................................................................................. 36 8. Certification ............................................................................................................................................