The West Riding Lunatic Asylum and the Making of the Modern Brain Sciences in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publishers for the People: W. § R. Chambers — the Early Years, 1832-18S0

I I 71-17,976 COONEY, Sondra Miley, 1936- PUBLISHERS FOR THE PEOPLE: W. § R. CHAMBERS — THE EARLY YEARS, 1832-18S0. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XEROXCompany , Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Sondra Miley Cooney 1971 PUBLISHERS FOR THE PEOPLE: W. & R. CHAMBERS THE EARLY YEARS, 1832-1850 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sondra Miley Cooney, B.A., A.M. The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS X wish to thank first those to whom I am indebted in Scotland. Had it not been for the assistance and co-operation of Mr. Antony S. Chambers, chairman of W. & R. Chambers Ltd, this study would never have become a reality. Not only did he initially give an unknown American permission to study the firm's archives, but he has subsequently provided whatever I needed to facilitate my research. Gracious and generous, he is a worthy descendent of the first Robert Chambers. All associated with the Chambers firm— directors and warehousemen alike— played an important part in my research, from answering technical queries to helping unearth records almost forgotten. Equally helpful in their own way were the librarians of the University of Edinburgh Library and the National Library of Scotland. Finally, the people of Edinburgh made a signif icant, albeit indirect, contribution. From them I learned something of what it means to a Scot to be a Scot. In this country I owe my greatest debt to my adviser, Professor Richard D. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

Special Articles

Walmsley Crichton-Browne’s biological psychiatry special articles Psychiatric Bulletin (2003), 27,20^22 T. WAL M S L E Y Crichton-Browne’s biological psychiatry Sir James Crichton-Browne (1840^1938) held a uniquely the brothers at the centre of British phrenology in distinguished position in the British psychiatry of his Edinburgh in the 1820s. time. Unburdened by false modesty, he called himself The central proposition of phrenology ^ that ‘the doyen of British medical psychology’ and, in the the brain is the organ of the mind ^ seems entirely narrow sense, he was indeed its most senior practitioner. unremarkable today. In the 1820s, however, it was a At the time of his death, he could reflect on almost half provocative notion with worrying implications for devout a century’s service as Lord Chancellor’s Visitor and a religious people. In Edinburgh, George Combe attached similar span as a Fellow of the Royal Society. great importance to drawing the medical profession into Yet,today,ifheisrememberedatall,itisasanearly an alliance and he pursued this goal with determination proponent of evolutionary concepts of mental disorder and occasional spectacular setbacks. (Crow, 1995). Summarising his decade of research at In 1825, Andrew Combe advanced phrenological the West Riding Asylum in the 1870s, Crichton-Browne ideas in debate at the Royal Medical Society and the proposed that in the insane the weight of the brain furore which followed resulted in the Society issuing writs was reduced, the lateral ventricles were enlarged and the prohibiting the phrenologists from publishing the burden of damage fell on the left cerebral hemisphere in proceedings. -

Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU English Faculty Publications English Spring 2000 Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel Cynthia N. Malone College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/english_pubs Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia Northcutt Malone. "Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel." Dickens Studies Annual 29 (Spring 2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel Cynthia Northcutt Malone While eighteenth-century British novels are peppered with women ''big with child"-Moll Flanders, Molly Seagrim, Mrs. Pickle-nineteenth century novels typically veil their pregnant characters. Even in nine teenth-century advice books by medical men, circumlocution and euphe mism obscure discussions of pregnancy. This essay explores the changing cultural significance of the female body from the mid-eigh teenth century to the early Victorian period, giving particular attention to the grotesque figure of Mrs. Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit. Through ostentatious circumlocution and through the hilariously grotesque dou bleness of Mrs. Gamp, Dickens both observes and ridicules the Victo rian middle-class decorum enveloping pregnancy in silence. And now one of the new fashions of our very elegant society is to go in perfectly light-coloured dresses-quite tight -witl1out a particle of shawl or scarf .. -

Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity

ORIGINS OF GENIUS This page intentionally left blank ~ ORIGINS OF GENIUS ~ Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity Dean Keith Simonton New York Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1999 Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1999 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 http://www.oup-usa.org Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Simonton, Dean Keith. Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity/ Dean Keith Simonton. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-19-512879-6 i. Genius. 2. Creative ability. 3. Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882. I. Title. BF412.S58 1999 153.9'8 — dc2i 98-45044 987654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper To all Darwinists This page intentionally left blank Contents ~ Preface IX 1. GENIUS AND DARWIN The Surprising Connections i 2. COGNITION How Does the Brain Create? 25 3. VARIATION Is Genius Brilliant—or Mad? 75 4. DEVELOPMENT Are Geniuses Born—or Made? 109 5. PRODUCTS By What Works Shall We Know Them? 145 6. -

A Critical Study of the Novels of John Fowles

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1986 A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES KATHERINE M. TARBOX University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation TARBOX, KATHERINE M., "A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES" (1986). Doctoral Dissertations. 1486. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE NOVELS OF JOHN FOWLES BY KATHERINE M. TARBOX B.A., Bloomfield College, 1972 M.A., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1976 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English May, 1986 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. This dissertation has been examined and approved. .a JL. Dissertation director, Carl Dawson Professor of English Michael DePorte, Professor of English Patroclnio Schwelckart, Professor of English Paul Brockelman, Professor of Philosophy Mara Wltzllng, of Art History Dd Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. I ALL RIGHTS RESERVED c. 1986 Katherine M. Tarbox Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. to the memory of my brother, Byron Milliken and to JT, my magus IV Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Some Edinburgh Medical Men at the Time of the Resurrectionists *

SOME EDINBURGH MEDICAL MEN AT THE TIME OF THE RESURRECTIONISTS * By H. P. TAIT, M.D., F.R.C.P.Ed., D.P.H. Senior Assistant Maternity and Child Welfare Medical Officer, Edinburgh Some time ago I was asked to give a paper to this combined meeting on some historical subject connected with the Edinburgh Medical s School. Since you are to be guests at a performance of Bridie " " The Anatomist tomorrow evening, it was suggested to me that I might speak of some of the medical men of Edinburgh at the time of the Resurrectionists. I hope that what I have to tell you tonight of may be of some interest and may enable you to obtain some sort " background for a more complete enjoyment of the play. The " of Anatomist centres round the figure of Dr Robert Knox, one he our leading anatomists in the twenties of the last century, and it was who gained an unwelcome notoriety by reason of his close association with Burke and Hare, the Edinburgh West Port murderers. Before proceeding to discuss some of the leaders of Edinburgh medi- cine at the time of Knox and the Resurrectionists, may I be permitted to give a brief outline of the Resurrectionist movement in this country- Prior to 1832, when the Anatomy Act was passed and the supply of anatomical material for dissection was regularised, there existed no legal means for the practical study of anatomy in Britain, save for the scanty and irregular material that was supplied by the gallows. Yet the law demanded that the surgeon possess a high degree of skill in his calling ! How, then, was he to obtain this skill without regular dissection ? The answer is that he obtained his material by illegal means, viz., rifling the graves of the newly-buried. -

Psychiatry in Descent: Darwin and the Brownes Tom Walmsley Psychiatric Bulletin 1993, 17:748-751

Psychiatry in descent: Darwin and the Brownes Tom Walmsley Psychiatric Bulletin 1993, 17:748-751. Access the most recent version at DOI: 10.1192/pb.17.12.748 References This article cites 0 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at: http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/17/12/748.citation#BIBL Reprints/ To obtain reprints or permission to reproduce material from this paper, please write permissions to [email protected] You can respond http://pb.rcpsych.org/cgi/eletter-submit/17/12/748 to this article at Downloaded http://pb.rcpsych.org/ on November 25, 2013 from Published by The Royal College of Psychiatrists To subscribe to The Psychiatrist go to: http://pb.rcpsych.org/site/subscriptions/ Psychiatrie Bulle!in ( 1993), 17, 748-751 Psychiatry in descent: Darwin and the Brownes TOMWALMSLEY,Consultant Psychiatrist, Knowle Hospital, Fareham PO 17 5NA Charles Darwin (1809-1882) enjoys an uneasy pos Following this confident characterisation of the ition in the history of psychiatry. In general terms, Darwinian view of insanity, it comes as a disappoint he showed a personal interest in the plight of the ment that Showalter fails to provide any quotations mentally ill and an astute empathy for psychiatric from his work; only one reference to his many publi patients. On the other hand, he has generated deroga cations in a bibliography running to 12pages; and, in tory views of insanity, especially through the writings her general index, only five references to Darwin, all of English social philosophers like Herbert Spencer of them to secondary usages. (Interestingly, the last and Samuel Butler, the Italian School of "criminal of these, on page 225, cites Darwin as part of anthropology" and French alienists including Victor R. -

9Th Grade 2016 Summer Reading All Forms

Hampton Christian Academy Upper School May 2016 Dear Parents, As we enter this summer, all of us—parents, students, and teachers—are excited about the well-earned break from the rigors of school. At the same time, however, we recognize that much hard-earned knowledge tends to slip away during the summer months unless we take measures to retain mental acuity. There is no question that one of the most valuable components to your student's academic success is a sustained pattern of reading. Students who are strong, avid readers are generally proficient students and competent test-takers. Hampton Christian Academy remains committed to doing all we can to develop our students’ reading skills and help them discover the life-long pleasure reading can bring to their lives. Each student in grades 7 - 11 is required to read a total of three books during the summer break. (Honors English students will have additional summer reading and writing assignments – see school website.) One of the three books has already been chosen for the student based on thematic content and grade level. This selected book will then be discussed the first week of school and a test will be given in class on the required book. This test will account for 50% of the student's summer reading test grade. An additional 25% will be earned by successfully completing a computerized Accelerated Reader quiz on a book from the grade level Accelerated Reader book list. AR quizzes consist of 10-20 questions focusing on reading comprehension. Students may drop by the school library on any Friday during the summer from 9 A.M. -

Stourton to Hunslet

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | LA17 LA17: Stourton to Hunslet High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H28 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report LA17: Stourton to Hunslet H28 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

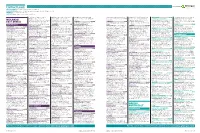

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. Plans Granted for 48 houses & 24 flats Job: Detail Plans Granted for cold storage Developer: Apex Design, 54 - 56 High Construction, Durhamgate, Green Lane, Suite Zest Energy Solutions Ltd, 9 Station Road, DONCASTER £0.8M Plans Submitted for warehouse (extension) Client: Lateral Property Group & building Client: Hexcel Corporation Pavement, Nottingham, NG1 1HW Tel: 0115 1, Spennymoor, County Durham, DL16 6FY Tel: Knowle, Solihull, West Midlands, B93 0HL Crossfield Lane and Skellow Client: Bolling Investments Ltd Agent: MIDLANDS/ Saint-Gobain Building Distribution Ltd Agent: Developer: Holt Architectural, Brambly 9508400 01388 813335 Contractor: Lark Energy Ltd, Spitfire Park, Planning authority: Doncaster Job: Detailed Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson, 13 Broomgrove MPSL Planning & Design Ltd, Commercial Hedge, Dereham Road, Colkirk, Fakenham, SOLIHULL £0.75M CAMBRIDGE £1.4M Northfield Road, Market Deeping, Plans Submitted for 16 flats (alterations) Road, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, S10 2LZ Tel: EAST ANGLIA House, 14 West Point Enterprise Park, Norfolk, NR21 7NQ Tel: 0844 800 3644 Tanworth & Camp Hill Cricket C, 174 Former Hilltop Day Centre, Primrose Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, PE6 8GY Tel: Client: St Leger Homes Doncaster Agent: St 0114 266