Protecting America's Workers Act: Modernizing Osha Penalties Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FALCON V, LLC, Et Al.,1 DEBTORS. CASE NO. 19-10547 CHAPT

Case 19-10547 Doc 103 Filed 05/21/19 Entered 05/21/19 08:56:32 Page 1 of 13 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: CASE NO. 19-10547 FALCON V, L.L.C., et al.,1 CHAPTER 11 DEBTORS. (JOINTLY ADMINISTERED) ORDER APPROVING FALCON V, L.L.C.'S ACQUISITION OF ANADARKO E&P ONSHORE LLC’S INTEREST IN CERTAIN OIL, GAS AND MINERAL INTERESTS Considering the motion of the debtors-in-possession, Falcon V, L.L.C., (“Falcon”) for an order authorizing Falcon’s acquisition of the interest of Anadarko E&P Onshore LLC (“Anadarko”) in certain oil, gas and mineral leases (P-13), the evidence admitted and argument of counsel at a May 14, 2019 hearing, the record of the case and applicable law, IT IS ORDERED that the Debtors are authorized to take all actions necessary to consummate the March 1, 2019 Partial Assignment of Oil, Gas and Mineral Leases (the “Assignment”) by which Anadarko agreed to assign its right, title and interest in and to certain oil, gas and mineral leases in the Port Hudson Field, including the Letter Agreement between Falcon and Anadarko attached to this order as Exhibit 1. IT IS FURTHERED ORDERED that notwithstanding anything to the contrary in this order, the relief granted in this order and any payment to be made hereunder shall be subject to the terms of this court's orders authorizing debtor-in-possession financing and/or granting the use of cash collateral in these chapter 11 cases (including with respect to any budgets governing or related to such use), and the terms of such financing and/or cash collateral orders shall control if 1 The Debtors and the last four digits of their respective taxpayer identification numbers are Falcon V, L.L.C. -

OFFICIAL BRAND BOOK of the STATE of LOUISIANA 2015 Brand

OFFICIAL BRAND BOOK OF THE STATE OF LOUISIANA 2015 Brand Book Contains all the Livestock Brands on record in the State Office at the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry in Baton Rouge, Louisiana up to the Close of Business on February 10, 2015 and as provided for in Paragraph 741, Chapter 7, of the Louisiana Revised Statutes of 1950. Issued by The Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry Animal Health and Food Safety Livestock Brand Commission P. O. Box 1951 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70821 Mike Strain DVM Commissioner Citizens of Louisiana: Louisiana’s livestock industry, valued at nearly $3 billion, contributes significantly to the state’s economy. Livestock producers face many challenges, like high input costs, unfavorable weather, an uncertain economy and an ever-changing regulatory environment. I understand these challenges and face them with you. As a practicing veterinarian, former state legislator and your Commissioner of Agriculture and Forestry, I believe our future is bright. Opportunities are great but we must lead the charge. If we take advantage of the latest advances in science and technology along with our abundant natural resources, infrastructure and proximity to major trade routes, Louisiana can grow agriculture and forestry into the future. The Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry (LDAF) Livestock Brand Commission inspectors investigate all aspects of farm- related crimes in the state, including livestock thefts (cattle, equine, hogs, emus, ostriches, turtles, sheep, and exotics), farm machinery and equipment. The Commission plays a large role in protecting producer’s property. The brands listed in this book assist inspectors in identifying and tracking the movement of livestock in Louisiana. -

ACLU Congressional Scorecard Evaluates Votes by Members of Congress on Key Legislation Affecting Civil Liberties and Civil Rights Since January 2017

SENATE SCORECARD Congressional Scorecard Congressional Civil Liberties Record in the Trump Era 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The ACLU Congressional Scorecard evaluates votes by members of Congress on key legislation affecting civil liberties and civil rights since January 2017. U.S. Senate Scorecard ...........................1 The ACLU’s Washington Legislative Office took a position on every piece of legislation Roll Call Appendix — Senate .............18 covered by this scorecard, including those receiving votes in the full House, the full U.S. House Scorecard ........................29 Senate, and several House and Senate committees. Descriptions of the measures are Roll Call Appendix — House .............95 included in the appendices. The scorecard gives each member of Congress an overall percentage number representing how well their votes align with ACLU positions and values. The start of the 115th Congress coincided with the start of the Trump administration, which has brought new attacks on civil rights and civil liberties. That reality makes it more important than ever that Congress fulfills its duty as a check on the executive branch and as a lawmaking body. Members’ votes represent their willingness to stand up and guard the rights that are fundamental to our democracy. And we will continue to hold them accountable for their votes. LEGEND: METHODOLOGY Green check mark indicates This scorecard consists of 36 House votes and 22 Senate votes on issues of concern for the alignment with ACLU ACLU. These votes took place between Jan. 3, 2017 and May 18, 2018. The percentage X Red X indicates lack of scores indicate how members of Congress voted in accordance with the ACLU’s positions alignment with ACLU on legislation. -

114Th Congress

ORMER TATE EGISLATORS IN THE TH ONGRESS as of January 21, 2014 F S L 11 4 C d UNITED STATES 1 Independent Frank Pallone Jr. (D) Jeff Duncan (R) SENATE Nebraska (Delegate) Florida Maine William Pascrell Jr. (D) Mick Mulvaney (R) Deb Fischer (R) Gus Bilirakis (R) Chellie Pingree (D) Albio Sires (D) Joe Wilson (R) 45 Total Alabama Corrine Brown (D) Nevada Mo Brooks (R) Ander Crenshaw (R) Maryland New Mexico South Dakota 23 Republicans Dean Heller (R) Mike Rogers (R) Ted Deutch (D) Elijah E. Cummings (D) Steve Pearce (R) Kristi Noem (R) Harry Reid (D) Mario Diaz-Balart (R) Andy Harris (R) 22 Democrats Alaska Lois Frankel (D) Steny Hoyer (D) New York Tennessee New Hampshire Don Young (R) John Mica (R) Chris Van Hollen (D) Joseph Crowley (D) Marsha Blackburn (R) New members in italics Alabama Jeanne Shaheen (D) Jeff Miller (R) Eliot Engel (D) Diane Black (R) Richard Shelby (R) Arizona William Posey (R) Massachusetts Brian Higgins (D) Steve Cohen (D) New Jersey Trent Franks (R) Dennis Ross (R) Katherine Clark (D) Hakeem Jeffries (D) Alaska Robert Menendez (D) Ruben Gallego (D) Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R) Bill Keating (D) Gregory W. Meeks (D) Texas NCSL STAFF Lisa Murkowski (R) Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Debbie Wasserman- Stephen Lynch (D) Grace Meng (D) Kevin Brady (R) New York Matt Salmon (R) Schultz (D) Jerrold Nadler (D) Joaquin Castro (D) Colorado Charles Schumer (D) David Schweikert (R) Daniel Webster (R) Michigan Charles Rangel (D) Henry Cuellar (D) Jeff Hurley Cory Gardner (R) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Frederica Wilson (D) Justin Amash (R) Jose Serrano -

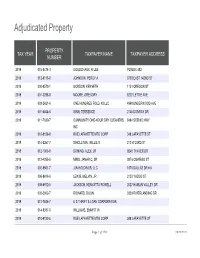

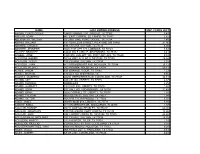

Adjudicated Property

Adjudicated Property PROPERTY TAX YEAR TAXPAYER NAME TAXPAYER ADDRESS NUMBER 2019 015-5474-3 GOUDCHAUX, R LEE PO BOX 482 2019 012-9113-0 JOHNSON, PERCY A 3703 EAST 142ND ST 2019 000-8573-1 GORDON, KENNETH 1151 OREGON ST 2019 001-3288-8 MOORE, GREGORY 8222 LETTIE AVE 2019 003-2621-6 ONE HUNDRED FOLD, #2 LLC 4968 UNDERWOOD AVE 2019 001-6564-6 GINN, TERRENCE 2145 DONRAY DR 2019 011-7630-7 COMMUNITY ONE-HOUR DRY CLEANERS, 8484 SCENIC HWY INC 2019 010-8126-8 RUE LAFAYETTE MTG CORP 348 LAFAYETTE ST 2019 014-2267-7 SINGLETON, WILLIE S 210 W 23RD ST 2018 012-1006-8 DOMINO, ALEX, JR 9248 THAYER DR 2019 012-4255-5 MIMS, JAMAR C, SR 3876 OSWEGO ST 2019 002-8561-7 JJN HOLDINGS, LLC 1676 DALLAS DR # A 2019 006-8616-6 LEWIS, MELVIN, JR 2153 YAZOO ST 2019 008-8972-5 JACKSON, KENYATTA POWELL 2027 HAMLIN VALLEY DR 2019 002-2002-7 RICHARD, DIJON 3329 RIVERLANDING DR 2019 012-2536-7 U S THRIFT & LOAN CORPORATION 2019 014-8387-0 WILLIAMS, EMMITT W 2019 010-8122-5 RUE LAFAYETTE MTG CORP 348 LAFAYETTE ST Page 1 of 1760 09/28/2021 Adjudicated Property TAXPAYER CITY STATE BLOCK/SQUARE PHYSICAL ADDRESS SUBDIVISION NAME ZIP NO HARTFORD CT 06141-0000 LELAND COLLEGE ANNEX 22 CLEVELAND OH 44120-0000 SCOTLAND ADDITION 22 PORT ALLEN LA 70767-0000 NORTHDALE 2 HOUSTON TX 77075-0000 2315 RHODES AVE BELFAIR HOMES BATON ROUGE LA 70805-0000 BANK 55 BATON ROUGE LA 70809- HERO PARK 2 BATON ROUGE LA 70807-0000 HOLIDAY ACRES BATON ROUGE LA 70801-0000 NORTH BROADMOOR RIVIERA BEACH FL 33404-0000 FORTUNE 9 BATON ROUGE LA 70807-0000 KELLY BATON ROUGE LA 70805-0000 1581 N 36TH ST EDEN PARK 31 BATON ROUGE LA 70806-0000 BANK 70 BATON ROUGE LA 70808-0000 2153 YAZOO HILLSIDE 2 HOUSTON TX 77090-0000 1827 ARIZONA ST SOUTH BATON ROUGE 7 ADDIS LA 70710-0000 4833 GREENWELL ST WILKERSON PLACE FORTUNE 51 FORTUNE 7 BATON ROUGE LA 70801-0000 NORTH BROADMOOR Page 2 of 1760 09/28/2021 Adjudicated Property FAIR MARKET LOT NO WARD LEGAL DESCRIPTION VALUE 7 2-2 200.00 3 1-5 2001. -

Name Last Known Address Unc

NAME LAST KNOWN ADDRESS UNC. FUNDS LEFT AARON, CHRISTOPHER 248822 ROBERT DR, PORTER, TX 77365 0.49 ABELAR, ADAM 401 EAST CORRAL, EL CAMPO, TX 77437 2.62 ABERNATHY, WILLIAM 32 EAST LAKE ROAD, DODGE, TX 77334 1.40 ABRAM, WILLIAM 1214 BAYLOUS STREET, PICAYUNE, MS 39466 21.96 ABSHIRE, CHANCE 826 CR 6769, DAYTON, TX 77535 6.00 ABSHIRE, JENNIFER 4625 71ST APT 173, LUBBOCK, TX 79424 3.82 ACALEY, BRADLEY 14693 HALF CIRCLE, SPLENDORA, TX 77372 0.41 ACEBAL, JOSE 1320 9TH AVE APT 105, PORT ARTHUR, TX 77640 0.34 ACEVEDO, BOBBIE 10166 HWY 321 LOT 3, DAYTON, TX 77535 24.34 ACEVEDO, JESUS 135 CR 4906, DAYTON, TX 77535 2.01 ACEVEDO, JUAN 4113 PRIMEROAST AVE, MCALLEN, TX 77584 25.72 ACEVEDO, PEDRO 303 ARVANA, HOUSTON, TX 77034 50.11 ACHEE, JASON 624 ORANGE, VIDOR, TX 77662 1.59 ACKER, MICHAEL 112 LILY RD, SHEPHERD, TX 9.66 ACOSTA, GILBERTO 26294 DEERCREEK RUN, CLEVELAND, TX 77327 44.81 ADAMS, AMY 438 CR 140, LIBERTY, TX 77575 6.87 ADAMS, DARRELL HOMELESS 2.25 ADAMS, GARRATT 1822 KIPLING, LIBERTY, TX 77575 1.80 ADAMS, JOHN 677 HALL RD, LOGANSPORT, LA 74109 31.48 ADAMS, ORAN 2626 CORNELL ST, LIBERTY, TX 77575 1.50 ADAMS, THERON 920 SOLON ST, GRETNA, LA 70053 1.94 ADAMS, VICTOR 1042 FM 770, RAYWOOD, TX 77582 3.58 AGER, JANET 3629 N MAIN #13, LIBERTY, TX 77575 0.30 AGNEW, EZELL 3115 RIVERBURT DR, INDALAPOIS, IN 46353 1.97 AGUILAR, BONNIE 7421 LOOP 540, BEASLEY, TX 77417 60.00 AGUILAR, JONATHAN 1557 MILMO DR, FORT WORTH, TX 76132 12.26 AGUILAR, JOSE 998 CHERRY CREEK #5, DAYTON, TX 77535 48.65 AGUILAR-MATA, APOLONIO 157 CR 6682, DAYTON, TX 77535 25.75 AGUILERA, MARCO 2319 HUNTER, TYLER, TX 75701 1.39 AGUILERA, RAJELIO 1301 NEVELL ST 1103, CLEVELAND, TX 77327 0.78 AGUILERA-MARTINEZ, IVAN 9900 RICHMOND, HOUSTON, TX 77042 9.28 AIKEN, VELDA 906 PEALA LOT 5, PASADENA, TX 77502 0.61 AILSS, JOSEPH 68 CR 2801, CLEVELAND, TX 77328 0.40 AISENBREY, CHANCE P.O. -

Supporting America's Educators: the Importance

SUPPORTING AMERICA’S EDUCATORS: THE IMPORTANCE OF QUALITY TEACHERS AND LEADERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, MAY 4, 2010 Serial No. 111–60 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and Labor ( Available on the Internet: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/house/education/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 56–130 PDF WASHINGTON : 2010 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND LABOR GEORGE MILLER, California, Chairman Dale E. Kildee, Michigan, Vice Chairman John Kline, Minnesota, Donald M. Payne, New Jersey Senior Republican Member Robert E. Andrews, New Jersey Thomas E. Petri, Wisconsin Robert C. ‘‘Bobby’’ Scott, Virginia Howard P. ‘‘Buck’’ McKeon, California Lynn C. Woolsey, California Peter Hoekstra, Michigan Rube´n Hinojosa, Texas Michael N. Castle, Delaware Carolyn McCarthy, New York Mark E. Souder, Indiana John F. Tierney, Massachusetts Vernon J. Ehlers, Michigan Dennis J. Kucinich, Ohio Judy Biggert, Illinois David Wu, Oregon Todd Russell Platts, Pennsylvania Rush D. Holt, New Jersey Joe Wilson, South Carolina Susan A. Davis, California Cathy McMorris Rodgers, Washington Rau´ l M. Grijalva, Arizona Tom Price, Georgia Timothy H. Bishop, New York Rob Bishop, Utah Joe Sestak, Pennsylvania Brett Guthrie, Kentucky David Loebsack, Iowa Bill Cassidy, Louisiana Mazie Hirono, Hawaii Tom McClintock, California Jason Altmire, Pennsylvania Duncan Hunter, California Phil Hare, Illinois David P. -

Amicus Briefs in Support of Either Or No Party

Nos. 18-1323 & 18-1460 In the Supreme Court of the United States JUNE MEDICAL SERVICES L.L.C., on behalf of its patients, physicians, and staff, d/b/a HOPE MEDICAL GROUP FOR WOMEN; JOHN DOE 1; JOHN DOE 2, Petitioners, v. DR. REBEKAH GEE, in her Official Capacity as Secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health, Respondent. DR. REBEKAH GEE, in her Official Capacity as Secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health, Cross-Petitioner, v. JUNE MEDICAL SERVICES L.L.C., on behalf of its patients, physicians, and staff, d/b/a HOPE MEDICAL GROUP FOR WOMEN; JOHN DOE 1; JOHN DOE 2, Cross-Respondents. ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF 207 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT AND CROSS-PETITIONER CATHERINE GLENN FOSTER STEVEN H. ADEN Counsel of Record KATIE GLENN NATALIE M. HEJRAN AMERICANS UNITED FOR LIFE 1150 Connecticut Ave NW Ste. 500 Washington, D.C. 20036 [email protected] Tel: (202) 741-4917 Counsel for Amici Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................... 1 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 3 I. June Medical lacks a “close” relationship with women seeking abortion and should not be presumed to have third-party standing. ........................... 3 A. Louisiana abortion clinics—including June Medical Services—have a long history of serious health and safety violations. ................................................... 5 B. Louisiana abortion doctors have a long history of professional disciplinary actions and substandard medical care. ............................................. 15 II. The Fifth Circuit appropriately applied the Casey standard and distinguished Hellerstedt to uphold Louisiana's act 620. -

Amicus Brief to Motion for Leave to File a Bill of Complaint

No. 155, Original ════════════════════════════════════════ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ____________________ STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, et al., Defendants. ____________________ On Motion for Leave to File a Bill of Complaint ____________________ Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae of U.S. Representative Mike Johnson and 105 Other Members of the U.S. House of Representatives in Support of Plaintiff’s Motion for Leave to File a Bill of Complaint and Motion for a Preliminary Injunction ____________________ WILLIAM J. OLSON PHILLIP L. JAUREGUI* JEREMIAH L. MORGAN JUDICIAL ACTION GROUP ROBERT J. OLSON 1300 I Street, NW HERBERT W. TITUS Suite 400 E WILLIAM J. OLSON, P.C. Washington, DC 20005 370 Maple Ave. W., Ste 4 (202) 216-9309 Vienna, VA 22180 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae *Counsel of Record December 10, 2020 ════════════════════════════════════════ List of Amici Curiae Amicus U.S. Representative Mike Johnson represents the Fourth Congressional District of Louisiana in the United States House of Representatives. Amicus U.S. Representative Gary Palmer represents the Sixth Congressional District of Alabama in the United States House of Representatives. Amicus U.S. Representative Steve Scalise represents the First Congressional District of Louisiana in the United States House of Representatives. Amicus U.S. Representative Jim Jordan represents the Fourth Congressional District of Ohio in the United States House of Representatives. Amicus U.S. Representative Ralph Abraham represents the Fifth Congressional District of Louisiana in the United States House of Representatives. Amicus U.S. Representative Rick W. Allen represents the Twelfth Congressional District of Georgia in the United States House of Representatives. -

Liberty County Sheriff's Office Inmate Trust Funds Unclaimed Property

LIBERTY COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE INMATE TRUST FUNDS UNCLAIMED PROPERTY The following individuals or businesses have unclaimed funds on file with Liberty County. To claim these funds, please contact the County Treasurer's Office at 936-336-4621. To check whether you have unclaimed funds on file with the State, visit the State Comptroller's website at: www.window.state.tx.us UNCLAIMED PID # NAME LAST KNOWN ADDRESS PROPERTY 461915 AARON CHRISTOPHER 248822 ROBERT DR PORTER TX 77365 $0.49 432502 ABELAR ADAM 401 EAST CORRAL EL CAMPO TX 77437 $2.62 441938 ABERNATHY WILLIAM 32 EAST LAKE ROAD DODGE TX 77334 $1.40 458714 ABRAM WILLIAM 1214 BAYLOUS STREET PICAYUNE MS 39466 $21.96 451740 ABRAMS LEON Not available. Use PID for lookup with S.O. Not available NA NA $13.58 472414 ABSHIRE CHANCE 826 CR 6769 DAYTON TX 77535 $6.00 465027 ABSHIRE JENNIFER 4625 71ST APT 173 LUBBOCK TX 79424 $3.82 241403 ACALEY BRADLEY 14693 HALF CIRCLE SPLENDORA TX 77372 $0.41 449915 ACEBAL JOSE 1320 9TH AVE APT 105 PORT ARTHUR TX 77640 $0.34 476565 ACEVEDO BOBBIE 10166 HWY 321 LOT 3 DAYTON TX 77535 $24.34 429530 ACEVEDO JESUS 135 CR 4906 DAYTON TX 77535 $2.01 452225 ACEVEDO JUAN 4113 PRIMEROAST AVE MCALLEN TX 77584 $25.72 434145 ACEVEDO PEDRO 303 ARVANA HOUSTON TX 77034 $50.11 459378 ACEVEDO BRENDA Not available. Use PID for lookup with S.O. Not available NA NA $46.00 450268 ACEVEDO ELIO Not available. Use PID for lookup with S.O. Not available NA NA $21.83 395817 ACHEE JASON 624 ORANGE VIDOR TX 77662 $1.59 426672 ACKER MICHAEL 112 LILY RD SHEPHERD TX $9.66 67751 ACOSTA GILBERTO 26294 DEERCREEK RUN CLEVELAND TX 77327 $44.81 431719 ADAMS AMY 438 CR 140 LIBERTY TX 77575 $6.87 478063 ADAMS DARRELL HOMELESS $2.25 288385 ADAMS GARRATT 1822 KIPLING LIBERTY TX 77575 $1.80 433752 ADAMS JOHN 677 HALL RD LOGANSPORT LA 74109 $31.48 439742 ADAMS ORAN 2626 CORNELL ST LIBERTY TX 77575 $1.50 467491 ADAMS THERON 920 SOLON ST GRETNA LA 70053 $1.94 75302 ADAMS VICTOR 1042 FM 770 RAYWOOD TX 77582 $3.58 485718 ADAMS JEREMY PAUL 160 KNIGHT ST DETROIT MI 49048 $0.08 430645 ADAMS CLAYTON Not available. -

Jaws Achompin' at Shrimp Boil

www.thepostnewspaper.net Galveston County Sheriff’s Sale BETTER RATES LOWER FEES IS HERE IN GREAT SERVICE THE POST WWW.JSCFCU.ORG TODAY! Just look inside! Vol. 11, No. 81 Wednesday, August 27, 2014 USPS 9400 75 cents INSIDE: High-school football previews – Dickinson Gators, Galveston Ball High Tors and this weeks schedule of games pg 9 Jaws achompin’ at shrimp boil Report and photos by Aaron Day, special guest writer Saturday brought yet another evening of family fun and shrimp eating as the Texas City- La Marque Chamber of Commerce held its annual shrimp boil and dance at Texas City’s Nessler Center. For more than 30 years, the shrimp boil has been a cherished occasion for a consistent crowd of roughly 1,000 people each year, with buckets upon buckets of shrimp, dancing, music and its renowned shrimp-eating contest. Along with the entertainment and food, this year’s event was particularly special as the chamber honored Dexter Guillory of Louisiana-based Riceland Crawfish to mark the fact that, after 22 years boiling shrimp for the event, he was retiring when the evening was done. Then it was time for the famous shrimp-eating contest. Wes Brown won first place for being Above left, county tax collector Cheryl Johnson whoops for joy as the first to finish his tray – a feat he performed before the MC could introduce all the contestants. “Team Johnson" member Wes Brown retains his shrimp-eating-contest Lasting quite a bit longer were local favorite Pee Wee Bowen and his band, who played the title; above right, chamber president Jimmy Hayley, left, and Talbert evening out with some good old classics that soon had the audience rockin ’n’ rollin’. -

Notice of Names of Persons Appearing to Be Owners of Abandoned Property

NOTICE OF NAMES OF PERSONS APPEARING TO BE OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY Pursuant to Chapter 523A, Hawaii Revised Statutes, and based upon reports filed with the Director of Finance, State of Hawaii, the names of persons appearing to be the owners of abandoned property are listed in this notice. The term, abandoned property, refers to personal property such as: dormant savings and checking accounts, shares of stock, uncashed payroll checks, uncashed dividend checks, deposits held by utilities, insurance and medical refunds, and safe deposit box contents that, in most cases, have remained inactive for a period of at least 5 years. Abandoned property, as used in this context, has no reference to real estate. Reported owner names are separated by county: Honolulu; Kauai; Maui; Hawaii. Reported owner names appear in alphabetical order together with their last known address. A reported owner can be listed: last name, first name, middle initial or first name, middle initial, last name or by business name. Owners whose names include a suffix, such as Jr., Sr., III, should search for the suffix following their last name, first name or middle initial. Searches for names should include all possible variations. OWNERS OF PROPERTY PRESUMED ABANDONED SHOULD CONTACT THE UNCLAIMED PROPERTY PROGRAM TO CLAIM THEIR PROPERTY Information regarding claiming unclaimed property may be obtained by visiting: http://budget.hawaii.gov/finance/unclaimedproperty/owner-information/. Information concerning the description of the listed property may be obtained by calling the Unclaimed Property Program, Monday – Friday, 7:45 am - 4:30 pm, except State holidays at: (808) 586-1589. If you are calling from the islands of Kauai, Maui or Hawaii, the toll-free numbers are: Kauai 274-3141 Maui 984-2400 Hawaii 974-4000 After calling the local number, enter the extension number: 61589.