The Name of Sabah and the Sustaining of a New Identity in a New Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil, Gas & Energy Sector

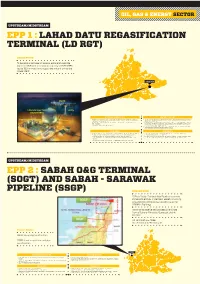

OIL, GAS & ENERGY SECTOR UPSTREAM/MIDSTREAM EPP 1 : LAHAD DATU REGASIFICATION TERMINAL (LD RGT) DESCRIPTION To develop a facilities to receive, store and vaporize imported LNG with a maximum capacity of 0.76 MTPA (up to 100 mmscfd) and supply the natural gas to the Power Plant lahad datu Berth LNG Storage Tank Jetty (0.76 MTPA) Key outcomes of the EPP / KPIs What needs to be done? Vaporization Station • Availability of natural gas supply at east coast of Sabah including Sandakan, Lahad Datu • Construction period of LNG Storage Tank which is the critical path of the project (normally and Tawau (also along the route) will take up to 24 months) • Transfer of technology and knowledge to local manpower and contractors who are involved • Front End phase of a project, where activities are mainly focused towards project planning with this project and contracting/bidding activities for the appointment of Frond End Engineering Design • Spurring the economy along the pipeline Consultant expected in mid-October 2011 • Evaluate and finalize the land lease of the reclaimed land of the proposed site with POIC. • Site Reclamation works is expected to start by Q1 2012 Key Challenges Mitigation Plan • Transporting major equipment and bulk materials from Sandakan to Lahad Datu (~200km) • Improvement of the road condition from Sandakan to Lahad Datu or consider for • Shortage of capable manpower due to simultaneous construction of LD power plant permanent/temporary jetty at Lahad Datu • Available manpower are lack of re-gas terminal construction skills (special) -

Utilising Local Cuisine to Market Malaysia As a Tourist Destination

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 144 ( 2014 ) 102 – 110 5th Asia Euro Conference 2014 Utilising local cuisine to market Malaysia as a tourist destination Mohd Hairi Jalisa,* , Deborah Chea, Kevin Markwellb aSouthern Cross University, Locked Mail Bag 4, Coolangatta QLD 4225, Australia bSouthern Cross University, Military Road (PO Box 157), East Lismore NSW 2480, Australia Abstract Travelling to a tourism destination can be made more exciting by experiencing the local cuisine. The variety of cooking methods and colourful ingredients blend together in a hot wok to create signature dishes of particular cuisines. Nevertheless, a cuisine needs to be clearly defined by definite individual characteristics so it is recognised. The primary objective of this study is to understand how Malaysian cuisine is used in marketing Malaysia as a tourist destination. Content analysis is used on selected Malaysian cuisine promotional materials such as brochures, travel guides, and webpages to extract relevant data. Results show that “close-up meal” had the highest image count from among the eight categories identified. As for text, ten categories were identified. “Creating desire” topped the list, followed by “sensory appeal”. The Malaysian Government is particular in the details selected for images of and narrative on the local cuisine. As a result, the marketing collateral could provide excitement and help tourists to anticipate the type of food experience that they can find when travelling in Malaysia. Additionally, it could help understanding what Malaysian cuisine is and develop the brand image. © 20142014 ElsevierThe Authors. Ltd. ThisPublished is an open by Elsevier access articleLtd. -

Malaysia, September 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Malaysia, September 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALAYSIA September 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Malaysia. Short Form: Malaysia. Term for Citizen(s): Malaysian(s). Capital: Since 1999 Putrajaya (25 kilometers south of Kuala Lumpur) Click to Enlarge Image has been the administrative capital and seat of government. Parliament still meets in Kuala Lumpur, but most ministries are located in Putrajaya. Major Cities: Kuala Lumpur is the only city with a population greater than 1 million persons (1,305,792 according to the most recent census in 2000). Other major cities include Johor Bahru (642,944), Ipoh (536,832), and Klang (626,699). Independence: Peninsular Malaysia attained independence as the Federation of Malaya on August 31, 1957. Later, two states on the island of Borneo—Sabah and Sarawak—joined the federation to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963. Public Holidays: Many public holidays are observed only in particular states, and the dates of Hindu and Islamic holidays vary because they are based on lunar calendars. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date); Chinese New Year (movable set of three days in January and February); Muharram (Islamic New Year, movable date); Mouloud (Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday, movable date); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (movable date in May); Official Birthday of His Majesty the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (June 5); National Day (August 31); Deepavali (Diwali, movable set of five days in October and November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date); and Christmas Day (December 25). Flag: Fourteen alternating red and white horizontal stripes of equal width, representing equal membership in the Federation of Malaysia, which is composed of 13 states and the federal government. -

Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume II: Chile, Greece, Malaysia

4. Malaysia Dagmar Hellmann-Rajanayagam* I. Introduction Malaysia has become one of the major political players in the South-East Asian region with increasing economic weight. Even after the economic crisis of 1997–98, despite defence budgets having been slashed, the country is still deter- mined to continue to modernize and upgrade its armed forces. Malaysia grappled with the communist insurgency between 1948 and 1962. It is a democracy with a strong government, marked by ethnic imbalances and affirmative policies, strict controls on public debate and a nascent civil society. Arms procurement is dominated by the military. Public apathy and indifference towards defence matters have been a noticeable feature of the society. Public opinion has disregarded the fact that arms procurement decision making is an element of public policy making as a whole, not only restricted to decisions relating to military security. An examination of the country’s defence policy- making processes is overdue. This chapter inquires into the role, methods and processes of arms procure- ment decision making as an element of Malaysian security policy and the public policy-making process. It emphasizes the need to focus on questions of public accountability rather than transparency, as transparency is not a neutral value: in many countries it is perceived as making a country more vulnerable.1 It is up 1 Ball, D., ‘Arms and affluence: military acquisitions in the Asia–Pacific region’, eds M. Brown et al., East Asian Security (MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass., 1996), p. 106. * The author gratefully acknowledges the help of a number of people in putting this study together. -

Hornbills of Borneo

The following two species can be easily confused. They can be recognized If you want to support Hornbill Conservation in Sabah, please contact from other hornbill species by the yellow coloration around the head and neck in Marc Ancrenaz at Hutan Kinabatangan Orangutan Conservation Project: the males. The females have black heads and faces and blue throat pouches. [email protected] HORNBILLS OF BORNEO Wrinkled hornbill (Aceros corrugatus): A large, mainly black hornbill whose tail is mostly white with some black at the base. Males have a yellow bill and more prominent reddish casque while females have an all yellow bill and casque. SABAH MALAYSIA The presence of hornbills in the Kinabatangan area is an indication that the surrounding habitat is healthy. Hornbills need forests for nesting and food. Forests need hornbills for dispersal of seeds. And the local people need the forests for wood Wreathed hornbill (Rhyticeros undulatus): A large, primarily black hornbill products, clean water and clean air. They are all connected: whose tail is all white with no black at the base. Both sexes have a pale bill with a small casque and a dark streak/mark on the throat pouch. people, hornbills and forests! Eight different hornbill species occur in Borneo and all are found in Kinabatangan. All are protected from hunting and/or disturbance. By fostering an awareness and concern of their presence in this region, hornbill conservation will be ensured for future generations. Credits: Sabah Forest Department, Sabah Wildlife Department, Hutan Kinabatangan Orangutan Conserva- tion Project (KOCP), Hornbill Research Foundation, Chester Zoo, Woodland Park Zoo. -

Sabah REDD+ Roadmap Is a Guidance to Press Forward the REDD+ Implementation in the State, in Line with the National Development

Study on Economics of River Basin Management for Sustainable Development on Biodiversity and Ecosystems Conservation in Sabah (SDBEC) Final Report Contents P The roject for Develop for roject Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background of the Study .............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................ 1 1.3 Detailed Work Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 ing 1.4 Implementation Schedule ............................................................................................. 3 Inclusive 1.5 Expected Outputs ......................................................................................................... 4 Government for for Government Chapter 2 Rural Development and poverty in Sabah ........................................................... 5 2.1 Poverty in Sabah and Malaysia .................................................................................... 5 2.2 Policy and Institution for Rural Development and Poverty Eradication in Sabah ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.3 Issues in the Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation from Perspective of Bangladesh in Corporation City Biodiversity -

“Fractured Basement” Play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat Formations As Hydrocarbon Reservoirs and Their Risk Factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia, Volume 69, May 2020, pp. 157 - 171 DOI: https://doi.org/10.7186/bgsm69202014 “Fractured basement” play in the Sabah Basin? – the Crocker and Kudat formations as hydrocarbon reservoirs and their risk factors Mazlan Madon1,*, Franz L. Kessler2, John Jong3, Mohd Khairil Azrafy Amin4 1 Advisor, Malaysian Continental Shelf Project, National Security Council, Malaysia 2 Goldbach Geoconsultants O&G and Lithium Exploration, Germany 3 A26-05, One Residences, 6 Jalan Satu, Chan Sow Lin, KL, Malaysia 4 Malaysia Petroleum Management, PETRONAS, Malaysia * Corresponding author email address: [email protected] Abstract: Exploration activities in the Sabah Basin, offshore western Sabah, had increased tremendously since the discovery of oil and gas fields in the deepwater area during the early 2000s. However, the discovery rates in the shelfal area have decreased over the years, indicating that the Inboard Belt of the Sabah Basin may be approaching exploration maturity. Thus, investigation of new play concepts is needed to spur new exploration activity on the Sabah shelf. The sedimentary formations below the Deep Regional Unconformity in the Sabah Basin are generally considered part of the economic basement which is seismically opaque in seismic sections. Stratigraphically, they are assigned to the offshore Sabah “Stages” I, II, and III which are believed to be the lateral equivalents of the pre-Middle Miocene clastic formations outcropping in western Sabah, such as the Crocker and Kudat formations and some surface hydrocarbon seeps have been reported from Klias and Kudat peninsulas. A number of wells in the inboard area have found hydrocarbons, indicating that these rocks are viable drilling targets if the charge and trapping mechanisms are properly understood. -

Table of Contents Daulat Tuanku!

Newsletter of the Consulate General of Malaysia in Frankfurt am Main – Summer 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS • DAULAT TUANKU! • ASIAN LIBRARY AT GOETHE UNIVERSITY • PHOTO EXHIBITION “UNITY IN DIVERSITY“ • FOOTBALL TOURNAMENT • CHINESE NEW YEAR • #NEGARAKU GATHERING • DIPLOMATIC COUNCIL GALA • TN50 • AMBIENTE 2017 • #NEGARAKU MALAYSIAN FAMILY DAY, DUISBURG • DINNER RECEPTION AT US CG RESIDENCE • IMEX 2017 • CONSULAR CORPS SPRING MEETING • TASTE OF THE WORLD • ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING, PERWAKILAN • ASEAN INVESTMENT FORUM • GMRT DÜSSELDORF • SEMINAR FOR GERMAN-MALAYSIAN UNIVERSITY • GMRT FRANKFURT • 'EID MUBARAK 2017' • CEBIT 2017 DAULAT TUANKU! Sultan Muhammad V has been formally installed as the Duli Yang Maha Mulia Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di- Pertuan Agong (King) of Malaysia on 24 April 2017. Tuanku Muhammad Faris Petra, the eldest son of Sultan Ismail Petra Ibni Almarhum Sultan Yahya Petra, was born in Kota Baru on 6 October 1969. He became Sultan of Kelantan in 2010, at the young age of 42, after succeeding his father. His Majesty received early education at Alice Smith International School in Kuala Lumpur. Later, he took up Diplomatic Studies at St. Cross College, Oxford University, and Islamic Studies at the Oxford Centre, Oxford University. He is the Chancellor of Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) and University Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia (UPNM). As Yang di-Pertuan Agong, he also holds full responsibility as Commander-in-Chief of the Malaysian Armed Forces. Pos Malaysia issued 1 stamp, in perforated and imperforate formats, and 1 miniature sheet on 25 April 2017 to commemorate the Sultan Muhammad V is described as a man of a generous and coronation of the new king of Malaysia, Sultan Muhammad V. -

Mammals of Borneo – Small Size on a Large Island

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2008) 35, 1087–1094 ORIGINAL Mammals of Borneo – small size on a ARTICLE large island Shai Meiri1,*, Erik Meijaard2,3, Serge A. Wich4, Colin P. Groves3 and Kristofer M. Helgen5 1NERC Centre for Population Biology, ABSTRACT Imperial College London, Silwood Park Aim Island mammals have featured prominently in models of the evolution of Campus, Ascot, UK, 2Tropical Forest Initiative, The Nature Conservancy, Balikpapan, body size. Most of these models examine size evolution across a wide range of Indonesia, 3School of Archaeology and islands in order to test which island characteristics influence evolutionary Anthropology, Australian National University, pathways. Here, we examine the mammalian fauna of a single island, Borneo, Canberra, Australia, 4Great Ape Trust of Iowa, where previous work has detected that some mammal species have evolved a Des Moines, IA, USA, 5Division of Mammals, relatively small size. We test whether Borneo is characterized by smaller mammals National Museum of Natural History, than adjacent areas, and examine possible causes for the different trajectories of Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, size evolution between different Bornean species. USA Location Sundaland: Borneo, Sumatra, Java and the Malay/Thai Peninsula. Methods We compared the mammalian body size frequency distributions in the four areas to examine whether the large mammal fauna of Borneo is more depauperate than elsewhere. We measured specimens belonging to 54 mammal species that are shared between Borneo and any of the other areas in order to determine whether there is an intraspecific tendency for Bornean mammals to evolve small body size. Using data on diet, body size and geographical ranges we examine factors that are thought to influence body size. -

Tourism and the Refashioning of the Headhunting Narrative in Sabah

“I Lost My Head in Borneo” “I Lost My Head in Borneo”: their understanding of the joke and thus Tourism and the guard their indigenousness and their status as human beings. I also argue that their use Refashioning of the of their headhunting heritage is a means of Headhunting Narrative in responding to the threats to their identities Sabah, Malaysia posed by the Malaysian state, which, in the process of globalization and nation building, has interpolated them into a Malaysian iden- Flory Ann Mansor Gingging tity, an identity that they seem to resist in Indiana University, Bloomington favor of their regional ones. This paper looks USA at what tourism’s refashioning of the headhunting narrative might suggest about Abstract how Sabah’s indigenous groups respond to their former colonization by the West and Although headhunting is generally believed how they imagine and negotiate their identi- to be no longer practiced in Sabah, Malay- ties within the constraints of membership sia, it is a phenomenon of the past that still within the state of Malaysia.1 exists in the collective consciousness of in- digenous groups, living through the telling and retelling of stories, not just by individu- spent a large part of my growing-up als, but also by the tourism industry. The years in Tamparuli, a small town near headhunting image and theme are ubiqui- the west coast of Sabah, a Malaysian I 2 tous in the tourist literature and campaigns. state in northern Borneo. A river divides They are featured on postcards, brochures, the town proper and the compound on and T-shirts (a particular favorite shows an which my family and I lived, so sojourns orangutan head with the caption “I lost my to the other side—to tamu (weekly mar- head in Borneo”). -

Curriculum Vite

BIODATA Ejria Binti Saleh Senior Lecturer, Borneo Marine Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia BIO SUMMARY - LIM AI YIM - MALAYSIA CURRICULUM VITE PERSONAL INFORMATION Name Name of Current Employer: Borneo Marine Research Institute Ejria Binti Saleh Universiti Malaysia Sabah Corresponding Address: E-mail: Borneo Marine Research Institute, [email protected]/[email protected] Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88999 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah Malaysia Tel: 6088-320000 ext: 2594 Fax: 6088-320261 NRIC: 710201-12-5042 Nationality: Malaysian Date of Birth: 01 January 1971 Sex: Female ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION Diploma/Degree Name of University Year Major Doctor of Philosophy Universiti Malaysia 2007 Physical Oceanography Sabah, Malaysia. Master Science University of Liverpool, 1997 Recent Environmental United Kingdom. Change Bachelor of Fisheries Universiti Putra 1996 Marine science Sc. (Marine Sciences) Malaysia, Malaysia. 1 Diploma in Fisheries Universiti Putra 1993 Fisheries Malaysia, Malaysia. RESEARCH PROJECTS Project Project Title Role Year Funder Status No. B-08-0- Tidal effects on salinity Co- 2002-2003 FRGS Completed 12ER intrusion and suspended Researcher sediment discharged in Manggatal River Estuary, Sabah SCF0019- Study of the factors regulating Co- 2006 -2009 Science Completed AGR-2006 the bloom mechanisms of Researcher Fund harmful algal species in Sabah SCF0015- Coastal processes and Co- 2006 -2009 Science Completed ENV-2006 geomorphologic Researcher Fund characteristics of major coastal towns in East Sabah for assessment -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula.