Archaeology in Newfoundland and Labrador 1981Opens in New Window

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

Fp802-170156 - Specs Cape Bauld

LIST OF DRAWINGS Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 DRAWING NO TITLE 02M1101A02401C1 Work Plan 02M1101A02401C2 Details LIST OF CONTENTS Section 00 01 11 Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 Section Title Pages 01 10 10 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS 12 01 16 10 MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY CANADA 3 01 33 00 SUBMITTAL PROCEDURES 5 01 35 24 SPECIAL PROCEDURES ON FIRE SAFETY REQUIREMENTS 5 01 35 29 HEALTH AND SAFETY REQUIREMENTS 12 01 35 43 ENVIRONMENTAL PROCEDURES 4 01 50 00 TEMPORARY FACILITIES 1 01 56 00 TEMPORARY BARRIERS AND ENCLOSURES 1 01 74 11 CLEANING 1 01 78 00 CLOSEOUT SUBMITTALS 1 02 41 16 SITEWORK, DEMOLITION AND REMOVAL 3 02 83 12 LEAD PAINT ABATEMENT MAXIMUM PRECAUTIONS 7 09 91 13 PAINTING 12 Appendix A: General Pictures Appendix B: Lead Paint Samples Appendix C: FHBRO Report GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS Section 01 10 10 Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 1.1 SCOPE .1 The work consists of the furnishing of all plant, labour, equipment and material for restoration of the Light Tower in Cape Bauld, NL, in strict accordance with specifications and accompanying drawings and subject to all terms and conditions of the Contract. The Cape Bauld Light tower is located in a rocky, barren landscape on the northern tip of Quirpon Island at the northern entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle. The lightstation is visible from L’Anse-aux-Meadows National Historic Site and World Heritage Site, located on the mainland. -

THE OCCURRENCE of GREENLAND and EUROPEAN BIRDS in NEWFOUNDLAND by L•Slm M

184] J. O.L. Roberts Bird-BandingJuly, 1971 CALL EPSIL (S,T,M,P) 1 E = E +FLOAT(N)*FLOAT(NB)*S**NC*X +FLOAT(N)*S**NB* XA*2. +S**N*P RETURN END C SAMPLE DATA 1 6 1810 5 2 0 0 864511 1 ß435 35 THE OCCURRENCE OF GREENLAND AND EUROPEAN BIRDS IN NEWFOUNDLAND By L•sLm M. TUCK* Newfoundland is a large island of 42,734 square miles situated in the North Atlantic Ocean between 46 ø and 52 ø north latitude. The Avalon Peninsula, its most southeasterly portion, is in the same latitude as the Bay of Biscay, France. Newfoundlandis some1,650 miles from the coast of Ireland, the nearest land in Europe. It is 850 miles from Cape Farewell, the most southerly point in Greenland. The physiographyof Newfoundland is quite similar to that of the adjacent Maritime Provinces. The coast is indented with bays and inlets and the island itself is a plateau which, sloping in a north- westerly direction, reacheselevations up to 1,500 feet in the almost mountainoushighlands along the west coast. A large part of the island's terrain is bleak and the soil is relatively shallow. In general, commercial forests are confined to the river valleys. Becauseit is on the eastern side of the North American continent, Newfoundland is influenced by continental air massesand exper- iences a wide range of summer and winter temperatures. More- over, as the island is virtually encircledby the cold waters of the Labrador Current, the sea moderatessummer and winter tempera- tures. Sea-icefrom the arctic regionsreaches Newfoundland in January (Figure 1) and in a normal year may surround the entire island except the south coast. -

Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution

Report of National Museum, 1889. — Lucas Plate CVI. o _2 Si a o a) -s «i Q z < —-I z LL 0. < I - o ~ I- •— UJ 3 cj 'Si Z o 03 EXPLORATIONS IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR IN 1887, MADE IN CONNECTION WITH THE CRUISE OF THE C. S, FISH COMMISSION' SCHOONER GRAMPUS* By Frederic A. Lucas, Assistant Curator of the Department of Comparative Anatomy. In tbe spring- of 1S87 the writer was detailed by Professor Baird to accompany tbe U. S. Fisb Commission schooner Grampus on a cruise to northeastern Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, primarily to obtain, if possible, bones of the Great Auk; secondarily to collect such other specimens as might be obtainable. Two years earlier Pro- fessor Baird had approved a proposed plan of visiting Funk Islaud, off Cape Freels, Newfoundland, a former breeding place of the Great Auk, in the hope of finding remains of that extinct bird, but the many difficulties in the way precluded carrying this plan into effect until the building of the Grampus and her projected trip made it feasible. From a scientific standpoint it was extremely desirable to secure bones of the Great Auk, since up to 1887 there were but nine skeletons of that species preserved in museums, only one being in the United States, while the U. S. National Museum possessed but a single bone. Even viewed commercially, a collection of Auk bones would be of considerable value, since the small number of existing specimens had caused them to bring a high price whenever brought into the market.! It was eminently fitting that a search for remains of the Great Auk should be undertaken in CDunection with fishery researches, since this bird once formed an important factor in the prosecution of the early * This report is supplementary to the paper by Mr. -

Aardvark Archaeology 2004 Archaeological Investigations at Ilhavo Park (Cjae-53) Duckworth Street and Plymouth Road, St

Provincial Archaeology Office July 8, 2020 Aardvark Archaeology 2004 Archaeological Investigations at Ilhavo Park (CjAe-53) Duckworth Street and Plymouth Road, St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador. 03.51 2004 Stage 1 HRA of the St. John’s Harbour Clean-Up. Part 1: Water Street, from Hutchings Street to Waldegrave Street. 2005 HRIA for the East Coast Hiking Trail Interpretation on the Mount, Renews, Newfoundland. 05.18 2005 Stage 1 HRIA of the Mortier Bay-North Atlantic Marine Service Centre, Powers Cove, NL. 05.53 2005 HRIA of the Murphy’s Cove Development Project. Collier Point, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador. 05.60 2005 HRIA of the South Brook Park Site (DgBj-03). 05.58 (on CD) 2006 Archaeological Monitoring of the 2006 Ferryland Beach Stabilization. 06.01 2006 Stage 1 HROA of 331 Water Street, St. John’s, NL. 2006 Archaeological Assessment of the Mockbeggar Plantation Provincial Historic Site Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 06.50 2006 Beneath the Big Store: Stage 2 Archaeological Assessment of the Mockbeggar Plantation Provincial Historic Site Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 06.50.01 2007 HRIA of Berry Island, Point Leamington Newfoundland and Labrador. 07.21 2008 Archaeological Assessment of the Bridge House Property (DdAg-03) Bonavista, Newfoundland and Labrador. 08.11 Adams, W. P. & J. B. Shaw 1967 Studies of Ice Cover on Knob Lake, New Québec. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 11(22), p. 88-96. Adney, Edwin Tappan & Howard I. Chapelle 1964 The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. AECOM 2012 Stage 2 Historical Impact Assessment 2012 Strange Lake-Quest Rare Minerals Project Field Survey Results Update. -

During the Second World War, Newfoundland Was an Occupied

The Gibraltar of America: The Establishment of American and Canadian Military Bases in Newfoundland during the Second World War and Their Impact on the People and Future of the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador © Paul W Collins, PhD. www.drpaulwcollins.com Prepared for: The Provincial Historic Commemorations Program Department of Business, Tourism, Culture, and Rural Development Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Box 8700, St. John’s, NL A1B 4J6 September 18, 2015 “The time will come when England will regard this island as the Gibraltar of America.”1 -Sir Robert Bond Newfoundland Prime Minister 1890 The Second World War and the subsequent arrival of thousands of American and Canadian military personnel marked a tremendous turning point in Newfoundland’s history. On the day the war began in September 1939, Newfoundland was a dispirited British dominion-in-abeyance off the east coast of Canada. The Colony was ruled by a London-appointed Commission of Government and kept afloat by loans and grants from the British Treasury.2 However, Newfoundland’s standing changed dramatically in the spring of 1940 with Nazi Germany’s victorious Blitzkrieg through Western Europe. Only Britain stood defiant, and on the other side of the Atlantic, Newfoundland was now viewed, not only as Canada’s “first line of defence,” but actually “the key to the western defence system.”3 In a very short time, Newfoundland boasted five military and civilian 1 Bond to the House of Assembly, 30 May 1890, as recorded in Proceedings, the St. John’s Evening Telegram, 13 June 1890. He is, of course, referring to the strategically invaluable British outpost at the Western entrance to the Mediterranean Sea. -

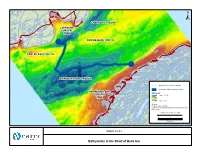

Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L'Anse Amour ! -80 -60 ! Forteau -50 ! ± LABRADOR TROUGH LABRADOR COASTAL -100 ZONE -80 -80 -1 00 L'Anse-au-Clair ! CENTRE BANK NORTH -90 ! -50 CENTRE BANK SOUTH -40 -60 0 -100 Green Island Cove 5 -60 ! - -80 -90 ! Pines Cove ! -100 Shoal Cove ! Sandy Cove ! NEWFOUNDLAND TROUGH -10 -20 Savage Cove ! -9 0 -30 Bathymetry Lines (10 m interval) 00 -1 Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor - ! 1 0 0 0 NEWFOUNDLAND -1 0 Bathymetry * COASTAL High : 127.09 -2 Flower's Cove ZONE0 ! -70 Low : -0.16 Sources: * Fugro Jacques (2007) Location of troughs and banks from Woodworth-Lynas et al. (1992). -60 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_406a ! 0 3 6 0 Kilometres -5 -80 ! ! FIGURE 10.5.2-2 ! Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Fhbro Heritage Character Statement Cape Bauld Lighttower Quirpon Island, Newfoundland and Labrador ______

FHBRO HERITAGE CHARACTER STATEMENT CAPE BAULD LIGHTTOWER QUIRPON ISLAND, NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ______________________________________________________________________________ FHBRO Number: 06-023 DFRP Number: 01729 Resource Name: Cape Bauld Lighttower Address: Quirpon Island, Newfoundland and Labrador FHBRO Status: “Recognized” Federal Heritage Building Construction: 1960-61 Designer: Department of Transport Original Function: lighthouse Current Function: lighthouse Modifications: no known modifications Custodian: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Description of Historic Place The Cape Bauld Lighttower is a tapered, concrete octagonal lighttower, topped by an octagonal, aluminum lantern. The gently tapered walls of the tower are painted white and rise to a flared cornice, above which a railed observation platform surrounds the red lantern. A vertical row of three windows with simple, concrete lintels runs up one side of the lighttower. The Cape Bauld Lighttower is located in a rocky, barren landscape on the northern tip of Quirpon Island at the northern entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle. The lightstation is visible from L’Anse-aux-Meadows National Historic Site and World Heritage Site, located on the mainland. The designation is confined to the footprint of the building. Heritage Value The Cape Bauld Lighttower is a “Recognized” Federal Heritage Building because of its historical associations, and its architectural and environmental values. Historical value: The Cape Bauld Lighttower is a very good example of the theme of aids to navigation in Canadian waters. As a landfall light with a range of 17 nautical miles located on the northern tip of Quirpon Island, it guides international and coastal shipping at the northern entry to the Strait of Belle Isle. The importance of a lighttower at this location is emphasized by the fact that the Dominion government built the first tower here soon after Confederation in what were then non-Canadian waters. -

Harp Seals, Man and Ice W

Harp Seals, Man and Ice w. • dab —4 _Ire ...Ob.._ 4r 'fflIOMMILF7 Frontispiece: Moulting patch of harp seals at the "Front" ice, Newfoundland, April 25, 1976. Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 114 Harp Seals, Man and Ice D.E. Sergeant Department of Renewable Resources, McGill University, Macdonald Campus, 21, 111 Lakesh ore, Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada H9X 1C0 Scientific Excellence Resource Protection & Conservation Benefits for Canadians DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS OTTAWA 1991 ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1991 Available in Canada through Associated Bookstores and other booksellers or by mail from Canada Communication Group - Publishing Supply and Services Canada Ottawa, Canada KlA 059 Catalogue No. Fs 41-31/114E ISBN: 0-660-14052-7 ISSN: 0706-6481 DF0/4419 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic , mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K lA 0S9. Printed on recycled paper Think Recycling! Pensez à recycler ! Published by Publié par Fisheries Pêches Mel and Oceans et Océans Communications Direction générale Directorate des communications Ottawa KlA 0E6 Communications Directorate Director, Scientific Publications: John Camp Editorial and Publishing Services: Gerald J. Neville Correct citation for this publication: SERGEANT, D. E. 1991. Harp seals, man and ice. Can. Spec. Publ. Fish. Aquat. Sci.114: 153 p. iv Contents Abstract/Résumé VIII Introduction and Acknowledgements IX Chapter I. Origins and Names 1 Summary 1 Classification and Evolution 1 Past Distribution 3 Vernacular Names and Other Terminology 7 Chapter II. -

Newfoundland Royal Commission 1933 Report (London: His Majesty's Stationary Office, 1934) 45

Amulree Report Amulree Report Project Title Page The Royal Warrant Introduction Table of Contents Chapter I In June 2002, Robert Hong, BA (Hons., MUN), MA (History, MUN), approached the Chapter II Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site with an offer to provide us with a digitized Chapter III version of the Amulree Commission Report. Earlier in the year he had entered the entire Chapter IV document into a word processor with the intention of making it available to the public in an Chapter V electronic format. Once we were satisfied with the accuracy of the electronic version, we were delighted and thankful to accept Robert Hong's offer. Chapter VI Chapter VII In most cases, what appears in the following pages is the text and layout as we received it. Chapter VIII There is one notable exception. A series of 65 black and white photographs are incorporated Chapter IX into the web site version. These photographs were part of the final report, but were presented Chapter X in their own album. Chapter XI Chapter XII Appendices Maps Photo Album Cover. Album cover of photographs furnished to the Newfoundland Royal Commission, August 1933. Courtesy of the Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives (Coll-207), Memorial University of Newfoundland Library, St. John's, Newfoundland. (35 kb) They have been embedded into appropriate locations on the web site to provide a visual representation, whenever possible, of places mentioned in the 1933 report. The images mainly depict the architecture and landscape of Newfoundland outport communities, several of which have since been resettled. There are a number of images of northern Labrador showing the rugged terrain along the coast. -

Inventory of Canada's Marine Renewable Energy Resources

INVENTORY OF CANADA’S MARINE RENEWABLE ENERGY RESOURCES A. Cornett CHC-TR-041 April 2006 INVENTORY OF CANADA’S MARINE RENEWABLE ENERGY RESOURCES Technical Report CHC-TR-041 April 2006 A. Cornett, Ph.D., P.Eng. Canadian Hydraulics Centre National Research Council Canada Ottawa, K1A 0R6, Canada CHC-TR-041 i Abstract This report presents results of studies conducted to quantify and map Canada’s renewable marine energy resources due to waves and tidal currents. These studies constitute the initial phase of a multi-year project that aims to create a digital atlas of Canadian renewable marine energy resources. The waters off Canada’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts are endowed with rich wave energy resources. The results presented herein define the scale of these resources, as well as their significant spatial and seasonal variations. The annual mean wave power along the 1,000 m isobath off Canada’s Pacific coast totals roughly 37,000 MW, equivalent to over 55% of Canadian electricity consumption, while the annual mean wave power along the 1,000 m isobath off Canada’s Atlantic coast sums to roughly 146,500 MW or more than double current electricity demand. The wave energy available in winter is generally four to seven times greater than in summer. It is important to recognize that due to various factors including environmental considerations, losses associated with power conversion, and socio-economic factors, only a fraction of the available wave energy resource can be extracted and converted into useful power. Even so, the Canadian resources are considered sufficient to justify further research into their development as an important source of renewable green energy for the future. -

The Newfoundland Royal Commission, 1933: Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage

Amulree Report Amulree Report Project Title Page The Royal Warrant Introduction Table of Contents Chapter I In June 2002, Robert Hong, BA (Hons., MUN), MA (History, MUN), approached the Chapter II Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage Web Site with an offer to provide us with a digitized Chapter III version of the Amulree Commission Report. Earlier in the year he had entered the entire Chapter IV document into a word processor with the intention of making it available to the public in an Chapter V electronic format. Once we were satisfied with the accuracy of the electronic version, we were delighted and thankful to accept Robert Hong's offer. Chapter VI Chapter VII In most cases, what appears in the following pages is the text and layout as we received it. Chapter VIII There is one notable exception. A series of 65 black and white photographs are incorporated Chapter IX into the web site version. These photographs were part of the final report, but were presented Chapter X in their own album. Chapter XI Chapter XII Appendices Maps Photo Album Cover. Album cover of photographs furnished to the Newfoundland Royal Commission, August 1933. Courtesy of the Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives (Coll-207), Memorial University of Newfoundland Library, St. John's, Newfoundland. (35 kb) They have been embedded into appropriate locations on the web site to provide a visual representation, whenever possible, of places mentioned in the 1933 report. The images mainly depict the architecture and landscape of Newfoundland outport communities, several of which have since been resettled. There are a number of images of northern Labrador showing the rugged terrain along the coast.