During the Second World War, Newfoundland Was an Occupied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

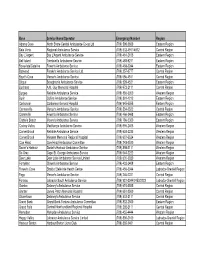

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2009 No. 43 EMBALMERS AND FUNERAL DIRECTORS ACT, 2008 NOTICE The following is a list of names and addresses of Funeral Homes 2009 to whom licences and permits have been issued under the Embalmers and Funeral Directors Act, cE-7.1, SNL2008 as amended. Name Street 1 City Province Postal Code Barrett's Funeral Home Mt. Pearl 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Barrett's Funeral Home St. John's 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Blundon's Funeral Home-Clarenville 8 Harbour Drive Clarenville NL A5A 4H6 Botwood Funeral Home 147 Commonwealth Drive Botwood NL A0H 1E0 Broughton's Funeral Home P. O. Box 14 Brigus NL A0A 1K0 Burin Funeral Home 2 Wilson Avenue Clarenville NL A5A 2B6 Carnell's Funeral Home Ltd. P. O. Box 8567 St. John's NL A1B 3P2 Caul's Funeral Home St. John's P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Caul's Funeral Home Torbay P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Central Funeral Home--B. Falls 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--GF/Windsor 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--Springdale 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Conway's Funeral Home P. O. Box 309 Holyrood NL A0A 2R0 Coomb's Funeral Home P. O. Box 267 Placentia NL A0B 2Y0 Country Haven Funeral Home 167 Country Road Corner Brook NL A2H 4M5 Don Gibbons Ltd. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

A GRAVITY SU VEY A ERN NOTR BAY, N W UNDLAND CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author's Permission) HUGH G. Ml rt B. Sc. (HOI S.) ~- ··- 223870 A GRAVITY SURVEY OF EASTERN NOTRE DAME BAY, NEWFOUNDLAND by @ HUGH G. MILLER, B.Sc. {HCNS.) .. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, Memorial University of Newfoundland. July 20, 1970 11 ABSTRACT A gravity survey was undertaken on the archipelago and adjacent coast of eastern Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. A total of 308 gravity stations were occupied with a mean station spacing of 2,5 km, and 9 gravity sub-bases were established. Elevations for the survey were determined by barometric and direct altimetry. The densities of rock samples collected from 223 sites were detenmined. A Bouguer anomaly map was obtained and a polynomial fitting technique was employed to determine the regional contribution to the total Bouguer anomaly field. Residual and regional maps based on a fifth order polynomial were obtained. Several programs were written for the IBM 360/40 computer used in this and model work. Three-dimensional model studies were carried out and a satisfactory overall fit to the total Bouguer field was obtained. Several shallow features of the anomaly maps were found to correlate well with surface bodies, i.e. granite or diorite bodies. Sedimentary rocks had little effect on the gravity field. The trace of the Luke's Arm fault was delineated. The following new features we r~ discovered: (1) A major structural discontinuity near Change Islands; (2) A layer of relatively high ·density (probably basic to ultrabasic rock) at 5 - 10 km depth. -

Sam Mclean Major Research Paper 095708700 Acknowledgements

Sam McLean Major Research Paper 095708700 Acknowledgements This project is not the paper that I proposed at the beginning of my MA studies. It is, as a result of those studies, much more focused in purpose, conception, and execution. This paper reflects the transition from classic naval historian to cultural historian and is the result of supervision by Professors Roger Sarty, Elizabeth Ewan, George Urbaniak, Geoffrey Hayes and Greta Kroeker. Their combined efforts led me to re-evaluate my historical interests and approach, and helped me to discover the importance of historical complexity as the foundation of understanding. Thanks also to the members of the Canadian Nautical Research Society who responded to my presentation of this paper at the society’s annual conference in June 2010 with helpful comments and recommendations. Finally, thanks again to Professor Roger Sarty for his patience and aid in the final stages of this project. 1 Sam McLean Major Research Paper 095708700 Introduction During the first part of the Second World War, Sir Herbert Richmond, professor at Cambridge University and the leading British naval historian, asserted that old-fashioned historical education of the Royal Navy’s officers had a deleterious effect on the navy’s operational performance. This paper is an examination of the impact of what Richmond called the “Blood and Thunder” school of history on the Royal Navy’s professional culture, and the effects of that culture on tactical decision-making during the period 1939 to 1943. The objective is to gain further insight into the institutional culture of the Royal Navy, greater understanding of how officers made tactical decisions, but most importantly endeavour to test more precisely the linkages between professional culture and decision-making in battle. -

![Confederation and Conspiracy: an Extended Essay on Greg Malone’S Don’T Tell the Newfoundlanders]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6797/confederation-and-conspiracy-an-extended-essay-on-greg-malone-s-don-t-tell-the-newfoundlanders-296797.webp)

Confederation and Conspiracy: an Extended Essay on Greg Malone’S Don’T Tell the Newfoundlanders]

Document generated on 09/30/2021 11:52 p.m. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies Confederation and Conspiracy An Extended Essay on Greg Malone’s Don’t Tell the Newfoundlanders Raymond B. Blake Volume 29, Number 2, Fall 2014 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/nflds29_2re01 See table of contents Publisher(s) Faculty of Arts, Memorial University ISSN 1719-1726 (print) 1715-1430 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Blake, R. B. (2014). Review of [Confederation and Conspiracy: An Extended Essay on Greg Malone’s Don’t Tell the Newfoundlanders]. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, 29(2), 303–317. All rights reserved © Memorial University, 2014 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ REVIEW ESSAY Confederation and Conspiracy: An Extended Essay on Greg Malone’s Don’t Tell the Newfoundlanders RaymOND B. BlakE Greg Malone. Don’t Tell the Newfoundlanders: The True Story of Newfound- land’s Confederation with Canada. Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2012. ISBN 978-0307401335 The contemporary award-winning British folk band Mumford & Sons poses an important question for all those who venture into history searching for an abso- lute truth. They poignantly ask in one of their popular lyrics, “How can you say that your truth is better than ours?” The true story is an elusive commodity in the retelling of the past, and perhaps the best we can hope for is some version of a truth. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

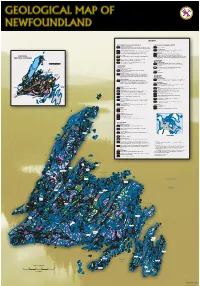

Geology Map of Newfoundland

LEGEND POST-ORDOVICIAN OVERLAP SEQUENCES POST-ORDOVICIAN INTRUSIVE ROCKS Carboniferous (Viséan to Westphalian) Mesozoic Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and minor carbonate rocks; intercalated marine, Gabbro and diabase siliciclastic, carbonate and evaporitic rocks; minor coal beds and mafic volcanic flows Devonian and Carboniferous Devonian and Carboniferous (Tournaisian) Granite and high silica granite (sensu stricto), and other granitoid intrusions Fluviatile and lacustrine sandstone, shale, conglomerate and minor carbonate rocks that are posttectonic relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and carbonate rocks; subaerial, bimodal Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks; may include some Late Silurian rocks Gabbro and diorite intrusions, including minor ultramafic phases Silurian and Devonian Posttectonic gabbro-syenite-granite-peralkaline granite suites and minor PRINCIPAL Shallow marine sandstone, conglomerate, limey shale and thin-bedded limestone unseparated volcanic rocks (northwest of Red Indian Line); granitoid suites, varying from pretectonic to syntectonic, relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies (southeast of TECTONIC DIVISIONS Silurian Red Indian Line) TACONIAN Bimodal to mainly felsic subaerial volcanic rocks; includes unseparated ALLOCHTHON sedimentary rocks of mainly fluviatile and lacustrine facies GANDER ZONE Stratified rocks Shallow marine and non-marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, including Cambrian(?) and Ordovician 0 150 sandstone, shale and conglomerate Quartzite, psammite, -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Fp802-170156 - Specs Cape Bauld

LIST OF DRAWINGS Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 DRAWING NO TITLE 02M1101A02401C1 Work Plan 02M1101A02401C2 Details LIST OF CONTENTS Section 00 01 11 Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 Section Title Pages 01 10 10 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS 12 01 16 10 MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY CANADA 3 01 33 00 SUBMITTAL PROCEDURES 5 01 35 24 SPECIAL PROCEDURES ON FIRE SAFETY REQUIREMENTS 5 01 35 29 HEALTH AND SAFETY REQUIREMENTS 12 01 35 43 ENVIRONMENTAL PROCEDURES 4 01 50 00 TEMPORARY FACILITIES 1 01 56 00 TEMPORARY BARRIERS AND ENCLOSURES 1 01 74 11 CLEANING 1 01 78 00 CLOSEOUT SUBMITTALS 1 02 41 16 SITEWORK, DEMOLITION AND REMOVAL 3 02 83 12 LEAD PAINT ABATEMENT MAXIMUM PRECAUTIONS 7 09 91 13 PAINTING 12 Appendix A: General Pictures Appendix B: Lead Paint Samples Appendix C: FHBRO Report GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS Section 01 10 10 Page 1 Restoration of the Cape Bauld Light Tower, NL F6879-177001 2017-07-26 1.1 SCOPE .1 The work consists of the furnishing of all plant, labour, equipment and material for restoration of the Light Tower in Cape Bauld, NL, in strict accordance with specifications and accompanying drawings and subject to all terms and conditions of the Contract. The Cape Bauld Light tower is located in a rocky, barren landscape on the northern tip of Quirpon Island at the northern entrance to the Strait of Belle Isle. The lightstation is visible from L’Anse-aux-Meadows National Historic Site and World Heritage Site, located on the mainland. -

Exerpt from Joey Smallwood

This painting entitled We Filled ‘Em To The Gunnells by Sheila Hollander shows what life possibly may have been like in XXX circa XXX. Fig. 3.4 499 TOPIC 6.1 Did Newfoundland make the right choice when it joined Canada in 1949? If Newfoundland had remained on its own as a country, what might be different today? 6.1 Smallwood campaigning for Confederation 6.2 Steps in the Confederation process, 1946-1949 THE CONFEDERATION PROCESS Sept. 11, 1946: The April 24, 1947: June 19, 1947: Jan. 28, 1948: March 11, 1948: Overriding National Convention The London The Ottawa The National Convention the National Convention’s opens. delegation departs. delegation departs. decides not to put decision, Britain announces confederation as an option that confederation will be on on the referendum ballot. the ballot after all. 1946 1947 1948 1949 June 3, 1948: July 22, 1948: Dec. 11, 1948: Terms March 31, 1949: April 1, 1949: Joseph R. First referendum Second referendum of Union are signed Newfoundland Smallwood and his cabinet is held. is held. between Canada officially becomes are sworn in as an interim and Newfoundland. the tenth province government until the first of Canada. provincial election can be held. 500 The Referendum Campaigns: The Confederates Despite the decision by the National Convention on The Confederate Association was well-funded, well- January 28, 1948 not to include Confederation on the organized, and had an effective island-wide network. referendum ballot, the British government announced It focused on the material advantages of confederation, on March 11 that it would be placed on the ballot as especially in terms of improved social services – family an option after all. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

Student and Youth Services Agreement.Xlsx

2015-16 Student and Youth Services Agreement Approvals Organization Location Project Approved Amount BOTWOOD BOYS AND GIRLS CLUB Botwood Youth Cordinator$ 40,100 CBDC TRINITY CONCEPTION CORPORATION Carbonear Community Youth Coordinator$ 87,500 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 229,714 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 90,155 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 57,232 (PACEE) COMMUNITY YOUTH NETWORK CORNER BROOK & AREA Corner Brook Impact $ 5,071 CONSERVATION CORPS NEWFOUNDLAND AND St. John's Green Team$ 579,600 LABRADOR FOR THE LOVE OF LEARNING, INC St. John's Watering the Seeds$ 115,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Entreprensurial Skills$ 35,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Outreach Coordinator$ 52,500 HARBOUR GRACE COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Grace Changing Lanes$ 60,301 KANGIDLUASUK STUDENT PROGRAM INC Nain Student Program$ 7,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Youth Opportinities Coop Program$ 100,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Wage Subsidies for MESD$ 11,186 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 522,993 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Graduate Transition to Employment (GTEP)$ 200,000 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 331,680 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 67,732 (PACEE) NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ASSOC OF Mount Pearl Youth Ventures$ 82,000 COMMUNITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATIONS SKILLS CANADA-NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St.