Building Yesterday's Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![2015 CLASS REUNIONS 1970S[ 2 ] - Massey University Aerial View CELEBRATING MASSEY UNIVERSITY CLASS REUNIONS 2015](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5191/2015-class-reunions-1970s-2-massey-university-aerial-view-celebrating-massey-university-class-reunions-2015-65191.webp)

2015 CLASS REUNIONS 1970S[ 2 ] - Massey University Aerial View CELEBRATING MASSEY UNIVERSITY CLASS REUNIONS 2015

2015 CLASS REUNIONS 1970s[ 2 ] - Massey University aerial view CELEBRATING MASSEY UNIVERSITY CLASS REUNIONS 2015 2015 saw a series of class reunions held on the Manawatü campus. This booklet contains contributions from the alumni and staff who attended, or wanted to attend and couldn’t. Massey University Alumni Relations thanks all those who came to the reunions or contributed to this booklet... and takes no responsibility for the content provided! 1970 - 1974 Wednesday 18 March 2015 1975 - 1979 Thursday 19 March 2015 Engineering and Technology Friday 20 March 2015 CELEBRATING MASSEY CLASS REUNIONS 2015 1970 1976 Engineering and Dick Hubbard Wendy Dalley Craig Irving Gary Daly Technology Chris Kelly Roy Hewson John Luxton Phyll Pattie Roger MacBean Jeff Plowman 1966 Lockwood Smith Peter Hubscher Gerry Townsend 1977 Buncha Ooraikul Rex Perreau Jan Henderson 1971 Nik Husain William Atkinson Mas Hashim 1969 Donald Bishop Dianne Kidd Jane (Henderson) Markotsis Greg Buzza Neville McNaughton Dalsukh Patel Wayne McIlwraith Jackie Sayers Robert (Bob) Stewart Sylvia Irwin Wakem Janis Swan (née Trout) 1970s 1978 See front of book 1972 Bruce Argyle Rod Calver Paul Moughan 1983 Peggy Koopman-Boyden Iris Palmer Fred McCausland Sue Suckling Donald McLeod Clive Palmer 1979 1986 1973 Brett Hewlett Ashley Burrowes Neville Chandler Eric Nelson Choon Ngee Gwee Jim Edwards Kathie Irwin Penny Haworth Barry O'Neil Rae Julian 1998 Carl Sanders-Edwards 1974 1980 Ashraf Choudhary Craig Hickson 1999 Ann Gluckman Janet Hunt David Hardie Joanna Giorgi Graham Henry 1975 Bruce Penny 2003 Robert Anderson Josh Hartwell Sharron Cole 1982 Rupinder Kauser Gregor Reid Steve Maharey 2007 Gerald Rys Logan Wait Margaret Tennant *PLEASE NOTE: Some contributions have been shortened due to available space. -

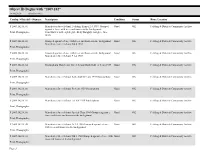

Fendalton/Waimairi Community Board Community Services Committee

FENDALTON/WAIMAIRI COMMUNITY BOARD 2006/07 PROJECT FUNDING - ANTICIPATED OUTCOMES PROGRESS REPORT - FEBRUARY 2007 Name of Group & Anticipated Outcomes Progress On Outcomes - Feb 2007 Amount Funded 1. a) To maintain a successful link with Breens Intermediate and Crossfire Trust has continued to deliver its range of services for further develop the ‘Life Skills’ programme; youth in the community over the past 6 months under the guidance Crossfire Trust of senior youth worker Caroline Forshey. b) To continue to run and maintain a Bishopdale Friday night drop- $10,000 in programme for young people; The programmes that have been delivered are: c) To organise and run at least 2 events to meet the needs of local - Weekly Peer Support Group at Breens Intermediate School youth e.g. camps, dances etc; - Ignite, a weekly small group mentoring programme - Flame, the Friday night programme for Years 7-8 d) To encourage volunteerism through maintaining a team of volunteer leaders who will receive ongoing support and training Caroline has also attended the weekly assemblies at Breens opportunities; Intermediate and on request from school staff, attended the school at lunchtimes to meet with students and build relationships with e) To promote networking and partnerships with other community them. agencies which provide support and opportunities for young people. The Friday night programme, Flame, continues to be very popular with young people from mainly Breens but also surrounding schools attending. Caroline has decided to pursue her University studies and finished with the Trust at Christmas time. The programmes will continue to be delivered through the leadership of the volunteers at St Margaret’s until Caroline’s position is filled. -

School Name Abbreviations Used in Sports Draws.Xlsx

SCHOOL NAME ABBREVIATIONS USED IN SPORTS DRAWS School Name School Abbreviation Aidanfield Christian School ADCS Akaroa Area School AKAS Allenvale School ALNV Amuri Area School AMUR Aranui High School ARAN Ashburton College ASHB Avonside Girls High School AVSG Burnside High School BURN Cashmere High School CASH Catholic Cathedral College CATH Cheviot Area School CHEV Christchurch Adventist School CHAD Christchurch Boys High School CBS Christchurch Girls High School CGHS Christchurch Rudolf Steiner School RSCH Christ's College CHCO Darfield High School DARF Ellesmere College ELLE Ferndale School FERN Hagley Community College HAGL Halswell Residential School HALS Hillmorton High School HLMT Hillview Christian School HLCS Hornby High School HORN Hurunui College HURU Kaiapoi High School KAIA Kaikoura High School KKOR Lincoln High School LINC Linwood College LINW Mairehau High School MAIR Marian College MARN Middleton Grange School MDGR Mt Hutt College MTHT Oxford Area School OXAS Papanui High School PPNU Rangi Ruru Girls School RRGS Rangiora High School RAHS Rangiora New Life School RNLS Riccarton High School RICC Shirley Boys High School SHIR St Andrew's College STAC St Bede's College STBD St Margaret's College STMG St Thomas of Canterbury College STCC Te Kura Kaupapa Maori o Te Whanau Tahi TAHI Te Kura Whakapumau I Te Reo Tuuturu Ki Waitaha TKKW Te Pa o Rakaihautu TPOR Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery UNLM Van Asch Deaf Education Centre VASH Villa Maria College VILL Waitaha Learning Centre WAIT . -

Unsettling Recovery: Natural Disaster Response and the Politics of Contemporary Settler Colonialism

UNSETTLING RECOVERY: NATURAL DISASTER RESPONSE AND THE POLITICS OF CONTEMPORARY SETTLER COLONIALISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY STEVEN ANDREW KENSINGER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DR. DAVID LIPSET, ADVISER JULY 2019 Steven Andrew Kensinger, 2019 © Acknowledgements The fieldwork on which this dissertation is based was funded by a Doctoral Dissertation Fieldwork Grant No. 8955 awarded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. I also want to thank Dr. Robert Berdahl and the Berdahl family for endowing the Daphne Berdahl Memorial Fellowship which provided funds for two preliminary fieldtrips to New Zealand in preparation for the longer fieldwork period. I also received funding while in the field from the University of Minnesota Graduate School through a Thesis Research Travel Grant. I want to thank my advisor, Dr. David Lipset, and the members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Hoon Song, Dr. David Valentine, and Dr. Margaret Werry for their help and guidance in preparing the dissertation. In the Department of Anthropology at the University of Minnesota, Dr. William Beeman, Dr. Karen Ho, and Dr. Karen-Sue Taussig offered personal and professional support. I am grateful to Dr. Kieran McNulty for offering me a much-needed funding opportunity in the final stages of dissertation writing. A special thanks to my colleagues Dr. Meryl Puetz-Lauer and Dr. Timothy Gitzen for their support and encouragement. Dr. Carol Lauer graciously offered to read and comment on several of the chapters. My fellow graduate students and writing-accountability partners Dr. -

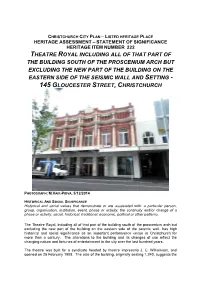

Theatre Royal Including All of That Part of the Building

CHRISTCHURCH CITY PLAN – LISTED HERITAGE PLACE HERITAGE ASSESSMENT – STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HERITAGE ITEM NUMBER 222 THEATRE ROYAL INCLUDING ALL OF THAT PART OF THE BUILDING SOUTH OF THE PROSCENIUM ARCH BUT EXCLUDING THE NEW PART OF THE BUILDING ON THE EASTERN SIDE OF THE SEISMIC WALL AND SETTING - 145 GLOUCESTER STREET, CHRISTCHURCH PHOTOGRAPH: M.VAIR-PIOVA, 5/12/2014 HISTORICAL AND SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE Historical and social values that demonstrate or are associated with: a particular person, group, organisation, institution, event, phase or activity; the continuity and/or change of a phase or activity; social, historical, traditional, economic, political or other patterns. The Theatre Royal, including all of that part of the building south of the proscenium arch but excluding the new part of the building on the eastern side of the seismic wall, has high historical and social significance as an important performance venue in Christchurch for more than a century. The alterations to the building and its changes of use reflect the changing nature and fortunes of entertainment in the city over the last hundred years. The theatre was built for a syndicate headed by theatre impresario J. C. Williamson, and opened on 25 February 1908. The size of the building, originally seating 1,240, suggests the popularity of theatre at the time. The building is the third in Gloucester Street to carry the name. Williamson was an American who settled in Australia, founding his company in 1879; many of the better productions which toured Australasia from the late nineteenth until the mid-twentieth centuries travelled were through Williamson. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Agenda of Waimāero/Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood Community Board

Waimāero Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood Community Board AGENDA Notice of Meeting: An ordinary meeting of the Waimāero/Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood Community Board will be held on: Date: Monday 26 August 2019 Time: 4.30pm Venue: Boardroom, Fendalton Service Centre, Corner Jeffreys and Clyde Roads, Fendalton Membership Chairperson Sam MacDonald Deputy Chairperson David Cartwright Members Aaron Campbell Linda Chen James Gough Aaron Keown Raf Manji Shirish Paranjape Bridget Williams 20 August 2019 Maryanne Lomax Manager Community Governance, Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood 941 6730 [email protected] www.ccc.govt.nz Note: The reports contained within this agenda are for consideration and should not be construed as Council policy unless and until adopted. If you require further information relating to any reports, please contact the person named on the report. To view copies of Agendas and Minutes, visit: https://www.ccc.govt.nz/the-council/meetings-agendas-and-minutes/ Waimāero/Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood Community Board 26 August 2019 Page 2 Waimāero/Fendalton-Waimairi-Harewood Community Board 26 August 2019 Part A Matters Requiring a Council Decision Part B Reports for Information Part C Decisions Under Delegation TABLE OF CONTENTS C 1. Apologies ..................................................................................................... 4 B 2. Declarations of Interest ................................................................................ 4 C 3. Confirmation of Previous Minutes ................................................................. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Canterbury Conservation Management Strategy

Canterbury Conservation Management Strategy Volume 1 Published by Department of Conservation/Te Papa Atawhai Private Bag 4715 Christchurch New Zealand First published 2000 Canterbury Conservation Management Planning Series No. 10 ISSN: 1171-5391-10 ISBN: 0-478-01991-2 Foreword Canterbury is rich in its variety of indigenous plants and animals, its historic heritage and relics, and its landscapes. Its physical features are dramatic, ranging from the majestic Southern Alps to the Canterbury Plains, from forested foothills to rocky coastlines and sandy beaches. These features also provide a wealth of recreational opportunities. The Department of Conservation’s Canterbury Conservancy is responsible for some 1293 units of land, and for the protection of important natural resources generally. To help manage these resources and activities the Conservancy, in consultation with the then North Canterbury and Aoraki Conservation Boards, has prepared a Conservation Management Strategy (CMS). The CMS sets out the management directions the Conservancy will take for the next ten years, the objectives it wants to achieve and the means by which it will achieve these. The draft CMS was released for public comment on 18 November 1995. Submissions closed on 1 April 1996, and 174 were received. Public oral submissions were heard in May and June of 1996. Consultation with Ngäi Tahu Papatipu Rünanga occurred from July to December 1996, and with Te Rünanga o Ngäi Tahu from July 1996 to May 1997. A summary of submissions and a decision schedule indicating the extent of acceptance of all submissions was prepared and given full consideration in revising the draft CMS. The revised draft CMS and summary of submissions was presented to the Conservation Boards for their consideration. -

Feilding Public Library Collection

Object ID Begins with "2009.102" 14/06/2020 Matches 4033 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location P 2009.102.01.01 Manchester Street School, Feilding. Primer 2-3 1939. Grouped Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive against a fence with trees and houses in the background. Print, Photographic Front Row L to R: eighth girl - Betty Doughty, last girl - June Wells. P 2009.102.01.02 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School Std 4 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.03 Grouped against a fence with trees and houses in the background Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Manchester Street School F 1-2 1939 Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.04 Studio photo Manchester Street School Basketball A Team 1939 Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.05 Manchester Street School Basketball B Team 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.06 Manchester Street School Prefects 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.07 Manchester Street School 1st XV 1939 Studio photo Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.08 Manchester Street School Special Class 1940 Grouped against a Good OK Feilding & Districts Community Archive fence with trees and houses in the background Print, Photographic P 2009.102.01.09 Manchester Street School -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

7707 Ashburton Glassworks

7707 Ashburton Glassworks (Former) 8 Glassworks Road and Bremners Road ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 270 Longbeach Station Homestead Longbeach Road ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 284 Church of the Holy Name (Catholic) Sealey Street ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 7593 Pipe Shed South Belt METHVEN Ashburton District Council 7753 Symonds Street Cemetery 72 Karangahape Road AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 94 Auckland War Memorial Museum 28 Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 122 Cenotaph Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 124 Domain Wintergardens Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4478 John Logan Campbell Monument 6 Campbell Cresent Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 2623 Clifton 11 Castle Drive Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 18 Highwic 40 Gillies Avenue Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 7276 Rocklands Hall 187 Gillies Avenue Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4471 Auckland Grammar School (Main Block) 87 Mountain Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4472 War Memorial, Auckland Grammar School 87 Mountain Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 116 St Andrew's Church (Anglican) 100 St Andrew's Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 7664 Auckland Municipal Destructor and Depot (Former) 210‐218 Victoria Street West and Union and Drake Streets Freemans Bay AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 98 Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Hall 71 Khyber Pass Road and Burleigh Street Grafton AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 5440 Cotswalds House 37 Wairakei