Bibliothèque Et Archives Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antwerp in 2 Days | the Rubens House

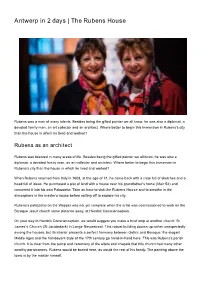

Antwerp in 2 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect Rubens was talented in many areas of life. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. On your way to Hendrik Conscienceplein, we would suggest you make a brief stop at another church: St James’s Church (St Jacobskerk) in Lange Nieuwstraat. This robust building dooms up rather unexpectedly among the houses, but its interior presents a perfect harmony between Gothic and Baroque: the elegant Middle Ages and the flamboyant style of the 17th century go hand-in-hand here. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Valuing Congestion Costs in Museums

Valuing congestion costs in small museums: the case of the Rubenshuis Museum in Antwerp Juliana Salazar Borda Master Cultural Economics & Cultural Entrepreneurship Faculteit der Historische en Kunstwetenschappen Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R. Vermeylen Second Reader: Dr. A. Klamer 2007 Summary Within the methodological framework of Contingent Valuation (CV), the purpose of this research was to find in the Rubenshuis Museum the ‘congestion cost’ or the amount visitors are willing to pay in order to avoid too many people inside. A number of 200 site interviews with museum visitors, either entering or leaving the museum, were made. The analysis of the results showed a strong tendency of visitors to prefer not congested situations. However, their WTP more for the ticket was low (€1.33 in average). It was also found that if visitors were women, were older, were better educated and had a bad experience at the museum, the WTP went up. In addition, those visitors who were in their way out of the museum showed a higher WTP than those ones who were in their way in. Other options to diminish congestion were also asked to visitors. Extra morning and night opening hours were the most popular ones among the sample, which is an alert to the museum to start thinking in improving its services. The Rubenshuis Museum is a remarkable example of how congestion can be handled in order to have a better experience. That was reflected in the answers visitors gave about congestion. In general, even if the museum had a lot of attendance, people were very pleased with the experience and they were amply capable to enjoy the collection. -

Antwerp in 3 Days | the Rubens House

Antwerp in 3 days | The Rubens House Rubens was a man of many talents. Besides being the gifted painter we all know, he was also a diplomat, a devoted family man, an art collector and an architect. Where better to begin this immersion in Rubens’s city than the house in which he lived and worked? Rubens as an architect When Rubens returned from Italy in 1608, at the age of 31, he came back with a case full of sketches and a head full of ideas. He purchased a plot of land with a house near his grandfather’s home (Meir 54) and converted it into his own Palazzetto. Take an hour to visit the Rubens House and to breathe in the atmosphere in the master’s house before setting off to explore his city. Rubens’s palazzetto on the Wapper was not yet complete when the artist was commissioned to work on the Baroque Jesuit church some distance away, at Hendrik Conscienceplein. The St Carolus Borromeus Church at Hendrik Conscienceplein is the epitome of Italian grandeur. With his knowledge of Italian architecture, Rubens undoubtedly contributed ideas for the façade, but his greatest achievements here are to be seen in the interior. Rubens designed the richly decorated chapel and its impressive marble high altar. Sadly, all that remains of the master’s 39 ceiling paintings are the sketches that are preserved in the church. The paintings themselves perished in a huge fire in 1718. The high altar merits particular attention: behind the enormous painting – it measures 4.0 x 5.35 metres – other works are concealed. -

Download PDF Van Tekst

De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 78-79 bron De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 78-79. Vereniging van Antwerpse Bibliofielen, Antwerpen 2000-2001 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_gul005200001_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. i.s.m. 7 [De Gulden Passer 2000-2001] Woord vooraf Ruim een halve eeuw geleden begon de bibliograaf Prosper Arents aan de realisatie van zijn vermetel plan om de bibliotheek van Pieter Pauwel Rubens virtueel te reconstrueren. In 1961 publiceerde hij in Noordgouw een bondig maar nog steeds lezenswaardig verslag over de stand, op dat ogenblik, van zijn werkzaamheden onder de titel De bibliotheek van Pieter Pauwel Rubens. Toen hij in 1984 op hoge leeftijd overleed, had hij vele honderden titels achterhaald, onderzocht en bibliografisch beschreven. Persklaar kon men zijn notities echter allerminst noemen, iets wat hij overigens zelf goed besefte. In 1994 slaagden Alfons Thijs en Ludo Simons erin onderzoeksgelden van de Universiteit Antwerpen / UFSIA ter beschikking te krijgen om Arents' gegevens electronisch te laten verwerken. Lia Baudouin, classica van vorming, die deze moeilijke en omvangrijke taak op zich nam, beperkte zich niet tot het invoeren van de titels, maar heeft ook bijkomende exemplaren opgespoord, Arents' bibliografische verwijzingen nagekeken en aangevuld en de uitgegeven correspondentie van P.P. Rubens opnieuw gescreend inzake lectuurgegevens. Een informele werkgroep, bestaande uit Arnout Balis, Frans Baudouin, Jacques de Bie, Pierre Delsaerdt, Marcus de Schepper, Ludo Simons en Alfons Thijs, begeleidde L. Baudouin bij haar ‘monnikenwerk’. Na het verstrijken van het mandaat van de onderzoekster bleef toch nog heel wat werk te verrichten om het geheel persklaar te maken. -

Print Through the Flemish Engraver and Art Dealer Jan Van Der Bruggen (1649–Ca

Young Man and Woman Studying a ca. 1688–92 Statue of Venus, by Lamplight oil on canvas 43.8 x 34.9 cm Godefridus Schalcken signed faintly lower right on the base of the (Made 1643 – 1706 The Hague) statue: “G. Schalcken” GS-103 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Young Man and Woman Studying a Statue of Venus, by Lamplight Page 2 of 11 How to cite Jansen, Guido. “Young Man and Woman Studying a Statue of Venus, by Lamplight” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/a-young-man-and-woman-studying-a-statue-of-venus-by-lamplight/ (accessed September 28, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Young Man and Woman Studying a Statue of Venus, by Lamplight Page 3 of 11 In this engaging and atmospheric picture, a young man is shown wearing a Comparative Figures painter’s beret and holding a drawing in his left hand that displays the contours of the plaster or marble statue of a kneeling nude woman in front of him. He points to this statue with his right hand while looking up at the young woman standing next to him, to whom he apparently explains the drawing and the statue. A copper oil lamp illuminates the scene, which is closed off on the right by a green curtain. -

April 2007 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 24, No. 1 www.hnanews.org April 2007 Have a Drink at the Airport! Jan Pieter van Baurscheit (1669–1728), Fellow Drinkers, c. 1700. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibited Schiphol Airport, March 1–June 5, 2007 HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Officers President - Wayne Franits Professor of Fine Arts Syracuse University Syracuse NY 13244-1200 Vice President - Stephanie Dickey Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Treasurer - Leopoldine Prosperetti Johns Hopkins University North Charles Street Baltimore MD 21218 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Marc-Chagall-Str. 68 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Ann Jensen Adams Krista De Jonge HNA News .............................................................................. 1 Christine Göttler Personalia ................................................................................ 2 Julie Hochstrasser Exhibitions ............................................................................... 2 Alison Kettering Ron Spronk Museum News ......................................................................... 5 Marjorie E. Wieseman Scholarly Activities Conferences: To Attend .......................................................... -

Canada Du Canada Acquisitions and Direction Des Acquisitions El Bibliographie Services Branch Des Services Bibliographiques 395 Wellirl['Lon Street 395

National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 01 Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions el Bibliographie services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellirl['lon Street 395. rue Weninglon Ottawa. Ontario Ottawa (Onlario) K1AON4 K1AON4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualité de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the dépend grandement de la qualité quality of the original thesis de la thèse soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualité ensure the highest quality of supérieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec l'université degree. qui a conféré le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualité d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser à . pages were typed with a poor désirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont été university sent us an inferior dactylographiées à l'aide d'un photocopy. ruban usé ou si l'université nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualité inférieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, même partielle, this microform is governed by de cette m!croforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, à la Loi canadienne sur le droit R.S.C. 1970, c. C·30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. C·30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subséquents~ Canada • Peter Paul Rubens and Colour Theory: an assessment of the evidence by Rüdiger Meyer AThesis submitled to the Faculty ofGraduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment • of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History McGill University Montreal, Canada March,1995 • © Rüdiger Meyer, 1995 National Ubrary Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et BiblIOgraphie Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

HNA November 2017 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 34, No. 2 November 2017 Peter Paul Rubens, Centaur Tormented by Peter Paul Rubens, Ecce Homo, c. 1612. Cupid. Drawing after Antique Sculpture, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg 1600/1608. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, © The State Hermitage Museum, Cologne © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln St. Petersburg 2017 Exhibited in Peter Paul Rubens: The Power of Transformation. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, October 17, 2017 – January 21, 2018 Städel Museum, Frankfurt, February 8 – May 21, 2018. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art www.hnanews.org E-Mail: [email protected] Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Paul Crenshaw (2017-2021) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Vice-President – Louisa Wood Ruby (2017-2021) The Frick Collection and Art Reference Library 10 East 71 Street New York NY 10021 Treasurer – David Levine Southern Connecticut State University 501 Crescent Street New Haven CT 06515 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents President's Message .............................................................. 1 In Memoriam ......................................................................... 2 Board Members Personalia ............................................................................... 4 Arthur -

Illustrated Biographies Of

—Ed ' l w s m z Revie . A eservi S r e base u on r ce t G rma l cat ons. znb d ng e i , d p e n e n pub i i g — e a or Most thoroughly and tastefully edited Sp ct t . ILLU STRATED BIOG RAPHIES OF THE G REAT ARTISTS. Each volumis l strat t fro 1 2 to 20 f a E rav n s r nte in the e i lu ed wi h m ull e ng i g , p i d est a er and o orna e ta c oth cov r s . 6d b m nn , b und in m n e , 3 . Froma R eview in TH E S P CTATO l E R u 1 8 . , y y 5, 79 It is high time that some thorough and general acquaintance with the works of these t ai t rs s o s r a a roa and it is a so c r o s to t k how o t r a s migh y p n e h uld be p e d b d , l u i u hin l ng hei n me ’ hav occ i sacr ic s in the or s art Wit o t the rese c of c o ar k o e up ed ed n he w ld he , h u p n e mu h p ul n w he co t v k of t r s If he f Io a hies a o t t c i or i iv . -

Peter Paul Rubens

T h e Gre at Masters in P ainting and S c ulpture Will iam n Editedby G . C . so P E T E R PA U L R U BEN S TH E GREAT MASTERS IN PAINTING AND L T R E SCU P U . Tbc ollowin Volumes Izam been issued rice s net at /I f g , p 5 . e . ’ ‘ B T I I E LLI S . O C . By A . TREETER R UN ELLE H I . L B SC By EADER SCOTT . M A E I . I COR R GG O S . By ELWYN BR NTON , M N R US HFO R’P H I LLI . I M . A CR E G . V By C E L , M BI the S B UR LA MA CC II I . DELLA RO B A . By ARCHE A RE DE RTO . SS . AND A L SA By H . GUINNE D N TE LLO . H R EA O A By OPE . W M P h . GER R D DOU . D . A By ARTIN , UDE N! I FER R R I . E T II E L H S GA O A By AL EY . FR N I . G O C. I I S Litt D . C . A A By E RGE W LL AM ON , M A GIOR GION E . H B C . By ER ERT OOK, M S. F. S GIOTTO . By A ON PERKIN M A . FR NS H LS . G S . D V S . A A By ERALD A IE , LUIN I . G C. I S Litt . D . By EORGE WILL AM ON , M R T T wE LL C U . -

Literaturergänzungen Zu Ulrich Heinen: Rubens Mit Verschränkten Armen (William Sanderson, Graphice, 1658). Zur Be- Gründung E

Literaturergänzungen zu Ulrich Heinen: Rubens mit verschränkten Armen (William Sanderson, Graphice, 1658). Zur Be- gründung einer Kunstpädagogik der Phantasie im Barock, in: Poiesis. Praktiken der Kreativität in den Künsten der Frühen Neuzeit, hrsg. von Valeska von Rosen, David Nelting und Jörn Stei- gerwald, Zürich und Berlin 2013, S. 327–375. Die Literaturergänzungen führen 1. die Anhänge sowie 2. Hinweise und erweiterte bibliographische Angaben zu einzelnen Fußnoten des Beitrags auf. Die Fußnotenverweise beziehen sich auf die Fußnoten des gedruckt erschienenen Artikel. 1. Anhänge Anhang I William Sanderson, Graphice. The Use of Pen and Pencil, or the most Excellent Art of Painting, Lon- don 1658. Preface [s.p.] […] It [sc. painting] is an Art I never professed: These Readings are gathered at my Study, accompa- nied with observations which I met with beyond Seas, and other Notions, pickt up from excellent Arti- zans abroad, and here at home; not without some experience by my own private practise, and alto- gether suiting my Genius. Which gave me occasion to say somewhat to our Painters, with their appro- bation, and desire, to reduce that discourse into a Method, legible to all, and so to render it profitable to the Publick; it being as well delightfull to be read, as usefull for practice, (I speak to Lovers of this Art, not to Masters): Yet, not altogether uncocerning the ordinary Artizan,138 whose former Instructions (hitherto) not reaching unto knowledge, rather hinders his progression from ever being excilent; him- self (perhaps) unacquainted with his own spirit, cannot so readily rise to estimation, though he labour much to make it his profession: For, the invention or election of the means, may be more effectual, than any inforcement or accumulation of endeavours.