Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patricia Ainslie Fonds (RBSC-ARC-1691)

University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Finding Aid - Patricia Ainslie fonds (RBSC-ARC-1691) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: March 04, 2020 Language of description: English University of British Columbia Library Rare Books and Special Collections Irving K. Barber Learning Centre 1961 East Mall Vancouver British Columbia V6T 1Z1 Telephone: 604-822-2521 Fax: 604-822-9587 Email: [email protected] http://rbsc.library.ubc.ca/ http://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca//index.php/patricia-ainslie-fonds Patricia Ainslie fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions -

Bryan Riley Ecatalog

The Drawers - Headbones Gallery Contemporary Drawings and Works on Paper Bryan Ryley Drawer’s Selection February 4, - March 11, 2006 Bryan Ryley Inaugural Drawer’s Selection February 4, 2006 - March 11, 2006 Artist Catalog, ‘Bryan Ryley - Headbones Gallery, The Drawers ’ Copyright © 2006, Headbones Gallery Images Copyright © 2006, Bryan Ryley Headbones commentary: Julie Oakes, filtered Copyright © 2006, Headbones Gallery Rich Fog Micro Publishing, printed in Toronto, 2006 Layout and Design, Richard Fogarty All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 copyright act or in writing from Headbones Gallery. Requests for permission to use these images should be addressed in writing to Bryan Ryley, c/o Headbones Gallery, 260 Carlaw Avenue, Unit 202B, Toronto, Ontario M4M 3L1 Canada Telephone/Facsimile: 416-465-7352 Email: [email protected] Director: Richard Fogarty www.headbonesgallery.com Bryan Ryley Drawer’s Selection To leave the mark of individuality, a sense of the intellect and spirit, is to wax poetic. Abstraction reveals what it left behind, a track of energy. Abstraction indicates the state of mind that the artist inhabited while he assumed the creative responsibility. Bryan Ryley leaves indicators and passes over the flame of insight to the viewer with a practiced hand. Ryley has never tied down the field of possibilities with inconsequential dribble. Throughout series past, he has held a strict abstract agenda, giving us paint, pencil, paper, canvas a “medium is the message” type of artist. -

Pierre Coupey Solo Exhibitions 2013 Clusters / Selected Work 1980

Pierre Coupey Solo Exhibitions 2013 Clusters / Selected Work 1980-2010, curators Astrid Heyerdahl / Darrin Morrison, Evergreen Cultural Centre / West Vancouver Museum [Catalogue]* 2012 New Work, Gallery Jones, Vancouver [Catalogue]* 2011 Featured Artist, Gallery Jones, West Vancouver 2010 Projects, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver Between Memory and Perception, Gallery Jones, Vancouver 2008 Counterpoint, Gallery Jones, Vancouver [Catalogue] 2006 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Cecilia Denegri Jette, Richmond Art Gallery (Gateway Theatre) Tangle, curator Darrin Martens, Burnaby Art Gallery [Catalogue] 2004 Paintings / Prints, curator Ingun Kemble, West Vancouver City Hall BlackWhiteGrey, curator Marcus Bowcott, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver Artist in Residence, The Urban Garage, West Vancouver 2002 Notations: Recent Work, Ballard Lederer Gallery, Vancouver 1999 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Patrick Montgomery, Evergreen Art Gallery [Catalogue] 1998 Notations 1994-1998, curator Paula Gustafson, Canadian Embassy Gallery, Tokyo [Catalogue] Work from the Notations Series, Montgomery Fine Art, Vancouver 1997 Work in Process: Drawings, Proofs, Prints, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver 1995 Notations 12-15 (For Eva), curator Carole Badgley, Seymour Art Gallery, North Vancouver From the 80’s: Trellis, Wedge, Montgomery Fine Art, Vancouver From the 70’s: Selected Journal Drawings / New Work on Paper, Atelier Gallery, Vancouver 1994 Notations: Painting the Lion from a Claw, Atelier Gallery, Vancouver -

Penticton Art Gallery 199 Marina Way Penticton, BC V2A 1H5

Arts Letter Vol. XXXIII No. 6 November / December 2013 Letter Vol.Arts XXXIII No. 6 Publication Agreement #40032521 November / December 2013 Joice M. Hall in her studio working on Descending Light. Photo by: Joice M. Hall Joice M. by: Photo Light. on Descending working studio her in Hall M. Joice Penticton Art Gallery 199 Marina Way Penticton, BC V2A 1H5 Arts Letter Vol. XXXIII No. 6 November / December 2013 PENTICTON ART GALLERY Mission Statement 199 Marina Way, Penticton, BC V2A 1H5 Tel: 250-493-2928 Fax: 250-493-3992 The Penticton Art Gallery exists to exhibit, interpret, preserve and E-mail: [email protected] promote the visual artistic heritage of the region, the province and www.pentictonartgallery.com the nation. www.twitter.com/pentartgallery The Arts Letter is the newsletter for members of Values Statement the Penticton Art Gallery. In setting the Mission Statement, the Board of Directors also identifies ISSN 1195-5643 the following values: Publication Agreement # 40032521 Community Responsibility The gallery interacts with the community by designing programs that in- GALLERY HOURS spire, challenge, educate and entertain while recognizing excellence in Tuesday to Friday - 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. the visual arts. Saturday & Sunday - noon to 5 p.m. Professional Responsibility The gallery employs curatorial expertise to implement the setting of exhi- GALLERY ADMISSION bitions, programs and services in accordance with nationally recognized Members Free, Students & Children Free professional standards of operation. Weekends Free Fiscal Responsibility Adult Non-Members $2 The gallery conducts the operations and programs within the scope of the financial and human resources available. -

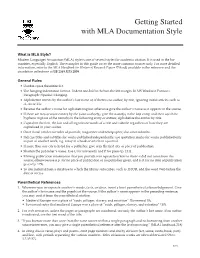

Getting Started with MLA Documentation Style

Getting Started with MLA Documentation Style What is MLA Style? Modern Languages Association (MLA) style is one of several styles for academic citation. It is used in the hu- manities, especially English. The examples in this guide cover the more common sources only. For more detailed information, refer to the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (7th ed) available in the reference and the circulation collections at LB 2369.G53 2009. General Rules • Double-space the entire list. • Use hanging indentation format. Indent one-half inch from the left margin. In MS Word use Format > Paragraph>Special>Hanging. • Alphabetize entries by the author’s last name or, if there is no author, by title, ignoring initial articles such as A, An or The. • Reverse the author’s name for alphabetizing but otherwise give the author’s name as it appears in the source. • If there are two or more entries by the same author(s), give the name(s) in the first entry, and then use three hyphens in place of the name(s) in the following entry or entries; alphabetize the entries by title. • Capitalize the first, the last and all significant words of a title and subtitle regardless of how they are capitalized in your source. • Omit initial articles for titles of journals, magazines and newspapers; also omit subtitles. • Italicize titles and subtitles for works published independently; use quotation marks for works published only as part of another work, e.g. essay in a book or article in a journal. • If more than one city is listed for a publisher, give only the first city as place of publication. -

Kelowna Art Gallery 2011 Annual Report

Kelowna Art Gallery Annual Report 2011 Cover image: Wanda Lock, She laughs every time she thinks about it, 2011, mixed media on paper, 22 x 30 in. (55.8 x 76.2 cm). Gift from the artist, 2008. Left to right: Marla O’Brien, Fern Helfand, Derek Sanders. Birgit Bennett, Leona Baxter, Deborah Owram, Nataley Nagy, Lori Van Rooijen, Stan Somerville, Laura Myles, Joanne Onrait. Absent: Ian Jones, Jim Meiklejohn, Tammy Moore, Mary Smith McCulloch, Sandra Kochan. The Kelowna Art Gallery Photo taken March 2012 gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the City of Kelowna, the Canada Council for the Arts, British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia, Board of Directors 2011 Central Okanagan School District #23, Regional District of Central Okanagan, Central Leona Baxter Birgit Bennett Okanagan Foundation, and President Fern Helfand our members, donors and sponsors. Jim Meiklejohn Tammy Moore Laura Myles Vice President Marla O’Brien (until April 2011) Joanne Onrait To engage, inspire, Derek Sanders and enrich the greater Marla O’Brien Mary Smith McCulloch community through the Vice President Stan Somerville exhibition, collection, (from May 2011) (from October 2011) and interpretation of Lori Van Rooijen visual art. Ian Jones (from October 2011) Treasurer Directors Deborah Owram Sandra Kochan Secretary City Liaison © Kelowna Art Gallery 2012 Design by Kyle L. Poirier Presidents’s Report All of us – the Board of Directors, staff and volunteers of the Kelowna Art Gallery, would like to take this opportunity to sincerely thank you, our members and friends, for your continued support of the Gallery and its mission to strengthen visual arts in the community. -

Pierre Coupey Solo Exhibitions 2015 New Work, Gallery Jones, Vancouver * 2014 New Work, Odon Wagner Contemporary, Toronto [C

Pierre Coupey Solo Exhibitions 2015 New Work, Gallery Jones, Vancouver * 2014 New Work, Odon Wagner Contemporary, Toronto [Catalogue]* 2013 Cutting Out the Tongue: Selected Work 1976-2012, curators Astrid Heyerdahl / Darrin Morrison, Art Gallery at Evergreen / West Vancouver Museum [Catalogue] Field Work, Gallery Jones, Vancouver 2011 Featured Artist, Gallery Jones, West Vancouver 2010 Between Memory and Perception, Gallery Jones, Vancouver Projects, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver 2008 Counterpoint, Gallery Jones, Vancouver [Catalogue] 2006 Tangle, curator Darrin Martens, Burnaby Art Gallery [Catalogue] Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Cecilia Denegri Jette, Richmond Art Gallery (Gateway Theatre) 2004 Paintings / Prints, curator Ingun Kemble, West Vancouver City Hall BlackWhiteGrey, curator Marcus Bowcott, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver Artist in Residence, The Urban Garage, West Vancouver 2002 Notations: Recent Work, Ballard Lederer Gallery, Vancouver 1999 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Patrick Montgomery, Art Gallery at Evergreen, Coquitlam [Catalogue] 1998 Notations 1994-1998, curator Paula Gustafson, Canadian Embassy Gallery, Tokyo [Catalogue] Work from the Notations Series, Montgomery Fine Art, Vancouver 1997 Work in Process: Drawings, Proofs, Prints, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver 1995 Notations 12-15 (For Eva), curator Carole Badgley, Seymour Art Gallery, North Vancouver From the 80’s: Trellis, Wedge, Montgomery Fine Art, Vancouver From the 70’s: Selected Journal Drawings / New -

Pierre Coupey

Pierre Coupey Solo Exhibitions 2020 TBA * 2019 New Work, Odon Wagner Contemporary, Toronto [Catalogue] * 2019 Manifest/Trace curator Vanessa Black, Seymour Art Gallery, North Vancouver * 2018 Rock Pool, Gallery Jones, Vancouver * 2017 Across / Between / Within, Odon Wagner Contemporary, Toronto [Catalogue] 2016 RaptureRupture, Gallery Jones, Vancouver 2016 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Darrin Morrison, West Vancouver Museum at West Vancouver Library 2014 Measures, Odon Wagner Contemporary, Toronto [Catalogue] 2013 Cutting Out the Tongue: Selected Work 1976-2012, curators Astrid Heyerdahl / Darrin Morrison, Art Gallery at Evergreen / West Vancouver Museum [Catalogue] 2013 Field Work, Gallery Jones, Vancouver 2011 Featured Artist, Gallery Jones, West Vancouver 2010 Between Memory and Perception, Gallery Jones, Vancouver 2010 Projects, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver 2008 Counterpoint, Gallery Jones, Vancouver [Catalogue] 2006 Tangle, curator Darrin Martens, Burnaby Art Gallery [Catalogue] 2006 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Cecilia Denegri Jette, Richmond Art Gallery (Gateway Theatre) 2004 Paintings / Prints, curator Ingun Kemble, West Vancouver City Hall 2004 BlackWhiteGrey, curator Marcus Bowcott, Capilano University Art Gallery, North Vancouver 2004 Artist in Residence, The Urban Garage, West Vancouver 2002 Notations: Recent Work, Ballard Lederer Gallery, Vancouver 1999 Requiem Notations I-IX, curator Patrick Montgomery, Art Gallery at Evergreen, Coquitlam [Catalogue] 1998 Notations 1994-1998, curator Paula Gustafson, -

Preview of the Visual Arts | November 2006

CALENDAR OF OPENINGS - PG 79 GALLERY INDEX - PG 75 THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA ■ BRITISH COLUMBIA ■ OREGON ■ WASHINGTON November/December/January 2006/07 www.preview-art.com Ben Van Netten Degrees of Transition Nov 9-26, 2006 Opening Reception: Thursday Nov 9, 6:30-8:30 pm Port Renfrew, 54 x 36 Inches oil on canvas on concave support Bruce Woycik Segue Nov 30-Dec 17, 2006 Opening Reception: Thursday Nov 30, 6:30-8:30 pm Lost in the 50's, 30 x 30 Inches oil on canvas the dark Dystopia Jan 11-28, 2007 Opening Reception: Thursday Jan 11, 6:30-8:30 pm Umbilical and the Drain, 23 x 26 Inches acrylic on panel FORT ST. JOHN BRITISH ALBERTA COLUMBIA PRINCE GEORGE EDMONTON QUEEN CHARLOTTE MCBRIDE ISLANDS WEST NORTH DEEP COVE WELLS VANCOUVER VANCOUVER BURNABY PORT MOODY NEW WESTMINSTER COQUITLAM VANCOUVER MISSION RICHMOND SURREY MAPLE RIDGE CHILLIWACK DELTA FORT LANGLEY ABBOTSFORD TSAWWASSEN WHITE ROCK WILLIAMS LAKE 100 MILE HOUSE CALGARY SALMON ARM BANFF SILVER STAR MOUNTAIN KAMLOOPS VERNON CAMPBELL RIVER KASLO WHISTLER KELOWNA COURTENAY COMOX MEDICINE HAT UNION BAY SUMMERLAND NELSON LETHBRIDGE SUNSHINE COAST VANCOUVER, BC PENTICTON CASTLEGAR PARKSVILLE OSOYOOS OLIVER TOFINO NANAIMO CHILLIWACK GRAND FORKS GULF ISLANDS DUNCAN BELLINGHAM SHAWNIGAN LAKE EASTSOUND SAANICH/SIDNEY ORCAS ISLAND LAKE COWICHAN SOOKE LA CONNER VICTORIA FRIDAY HARBOR, SAN JUAN ISLAND PORT LANGLEY ANGELES KIRKLAND SPOKANE SEATTLE BELLEVUE TACOMA OLYMPIA WASHINGTON ASTORIA SEASIDE LONGVIEW CANNON BEACH GOLDENDALE PORTLAND MCMINVILLE SHERIDAN SALEM PACIFIC CITY OREGON EUGENE ASHLAND 6 PREVIEW COVER: Alessandro Papetti, Madrid (2006), detail, oil on linen [Buschlen Mowatt Gallery, Vancouver BC, Nov 1-30] ALBERTA Vol. -

Kelowna Art Gallery 2013 Annual Report

Annual Report 2013 1 2 Kelowna Art Gallery Annual Report 2013 Cover image: Gordon Smith (Canadian, b. 1919), SB 26, 1974, watercolour, 15 x 18 in. (38.1 x 45.7 cm). Gift of the Estate of Paul and Edwina Heller in 2013. Mission: To engage, inspire, and enrich the greater community through the exhibition, collection, and interpretation of visual art. Left to right: Amy Zurrer, Stan Somerville, Marla O’Brien, Paul Mitchell Q.C., Mary Smith McCulloch, Nataley Nagy, Laura Myles, Derek Sanders, Clayton Gall. Photo taken March 2014 Board of Directors 2013 Marla O’Brien Clayton Gall Sandra Kochan President Fern Helfand City Liaison Mary Smith McCulloch Derek Sanders Joanne McKechnie Treasurer Paul Mitchell Q.C. Laura Myles The Kelowna Art Gallery Stan Somerville gratefully acknowledges the Amy Zurrer financial assistance of the City of Kelowna, The Canada Directors Council for the Arts, British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia, Central Okanagan School District #23, Regional District of Central Okanagan, Central Okanagan Foundation, and our members, donors and sponsors. © Kelowna Art Gallery 2014 Design by Kyle L. Poirier 1 President’s Report The year 2013 has been an incredibly successful one of ground-breaking creativity and inspiring community engagement for the Kelowna Art Gallery. As Board Chair, it has been my honour to work with a dedicated and talented staff team, fellow Board members, and volunteers to bring the KAG’s vision to life. This year, we were inspired to look at art through a new lens with the Just Imagine exhibition, which showcased works by people with visual impairments. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Rethinking Colonial Pasts while other contributions address through Archaeology topics pertaining to Canada, Africa (Mozambique, Uganda), the Caribbean Neal Ferris, Rodney Harrison, (Jamaica, Dominica), Australia, and and Michael V. Wilcox, editors Ireland. Its objective is to present a synthesis of current theoretical trends and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014 528 100 00 contemporary research on the archaeology . pp. £ . cloth. of the colonized, and to highlight Douglas E. Ross the value of revisionist approaches in Simon Fraser University decolonizing our understanding of the past. As such, contributors seek to highlight the relevance of their research to descendant communities and the wider ethinking Colonial Pasts through field of archaeology. RArchaeology is an important and The book is divided into four sections: well crafted synthesis by leading (1) contemporary issues in the archaeology scholars, marking a coming of age for of Indigenous-European interactions; the archaeology of Indigenous peoples (2) case studies on colonial landscapes, in colonial settler societies. To some communities, households, and identities; extent, the title misrepresents the (3) examples of marginalized groups volume’s explicit focus on colonized facing challenges similar to those of peoples, but this is a conscious choice Indigenous peoples; and (4) studies by the editors. They find “archaeology seeking to reframe the conceptual basis of the colonized” a problematic concept of the field and situate archaeology and feel the book’s broad themes within contemporary political contexts warrant the more inclusive title. and global discourses. Central themes This edited volume has twenty unifying the chapters include a colonized- substantive chapters, bookended by an centric view of the colonial process, introduction plus two brief commentaries comparative studies of everyday life across and an afterword. -

Regular Agenda

REGIONAL DISTRICT OF NORTH OKANAGAN BOARD of DIRECTORS MEETING Wednesday, January 6, 2016 4:00 p.m. REGULAR AGENDA A. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 1. Board of Directors – January 6, 2016 (Opportunity for Introduction of Late Items) (Opportunity for Introduction of Late Items – In Camera Agenda) RECOMMENDATION 1 (Unweighted Corporate Vote – Simple Majority) That the Agenda of the January 6, 2016 regular meeting of the Board of Directors be approved as presented. B. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 1. Board of Directors – December 9, 2015 RECOMMENDATION 2 Page 1 (Unweighted Corporate Vote – Simple Majority) That the minutes of the December 9, 2015 meeting of the Board of Directors be adopted as circulated. 2. Committee of the Whole – December 9, 2015 RECOMMENDATION 3 Page 12 (Unweighted Corporate Vote – Simple Majority) That the minutes of the December 9, 2015 meeting of the Committee of the Whole be adopted as circulated. C. DELEGATIONS 1. Agricultural Land Commission Application RUECHEL, C. c/o TASSIE, P. [File No. 15-0431-E-ALR] 690 Highway 6, Electoral Area “E” [See Item E.1] Board of Directors Agenda – Regular - 2 - January 6, 2016 D. UNFINISHED BUSINESS E. NEW BUSINESS 1. Agricultural Land Commission Application RUECHEL, C. c/o TASSIE, P. [File No. 15-0431-E-ALR] 690 Highway 6, Electoral Area “E” − Staff report dated November 13, 2015 RECOMMENDATION 4 Page 14 (Unweighted Corporate Vote – Simple Majority) That as recommended by the Electoral Area Advisory Committee, the application of Charlotte Ruechel c/o Peter Tassie under Section 21(2) of the Agricultural Land Commission Act to subdivide the property legally described as NW ¼, Sec 14, Twp 57, ODYD and located at 690 Highway 6, Electoral Area “E” be authorized for submission to the Agricultural Land Commission.