Exploring the Equity Dimensions of US Bicycle Sharing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bikesharing and Bicycle Safety Department of Transportation MTI Report 12-02MTI Report

MTI Funded by U.S. Department of Services Transit Census California of Water 2012 Transportation and California Bikesharing and Bicycle Safety Department of Transportation MTI ReportMTI 12-02 MTI Report 12-54 December 2012 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to Founder, Honorable Norman Joseph Boardman (Ex-Officio) Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2016) Michael Townes* (TE 2017) be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Mineta (Ex-Officio) Chief Executive Officer Principal and Chair of Board Senior Vice President Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Lea+Elliot, Inc. Transit Sector, HNTB Transportation Centers Program, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. Vice Chair Anne Canby (TE 2017) Will Kempton (TE 2016) Bud Wright (Ex-Officio) Hill & Knowlton, Inc. Director Executive Director Executive Director OneRail Coalition Transportation California American Association of State The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface Honorary Chair, Honorable Bill Highway and Transportation Officials transportation modes. -

Online Version of the Questions (Updated Regularly): Q: Will Motorcyclists Be Able to Lane Share Anywhere?

Online version of the questions (updated regularly): https://laneshareoregon.com/#faqs Q: Will motorcyclists be able to lane share anywhere? No. Only under the limited conditions proposed in the bill, summarized below. Traffic on the road: must be stopped, or moving at 10 miles per hour or less The rider: may travel no more than 10 miles per hour faster than traffic must not impede the normal and reasonable movement of traffic must safely merge with traffic, if traffic speed exceeds 10 miles per hour Riders cannot lane share: between a traffic lane and the curb and bicycle lane (on either side) between a traffic lane and a row of parked vehicles (on either side) in a school zone Riders should also use common sense when lane sharing, and err on the side of caution: "If you can't fit, don't split". The California Highway Patrol has defined guidelines for safe lane sharing. Q: Is lane sharing dangerous for pedestrians and bicyclists? Not lane sharing under HB2314. HB2314 legalizes lane sharing only on roads with posted speeds of 50 mph or greater: highways and freeways. Most people don’t walk or bicycle on or across these roads, even if they’re allowed to. Also, under HB2314 motorcycles may not lane-share on the right hand side of the right hand lane, next to the curb, shoulder or bicycle lane. HB2314 was written this way to give additional protection to pedestrians and bicyclists. Commenting on the specific constraints in HB2314, Portland’s Bureau of Transportation wrote “our most serious concerns of threats to pedestrian and bike safety are addressed”. -

Bicycle Public Hearing Summary Report

BICYCLE PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY REPORT DALLAS AND FORT WORTH DISTRICTS IN COORDINATION WITH NORTH CENTRAL TEXAS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS OCTOBER 2014 Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 CONTENTS 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS/RECOMMENDATIONS 2. PUBLIC HEARING COMMENT AND RESPONSE REPORT 3. PUBLIC HEARING POLL RESULTS 4. PUBLIC HEARING SURVEY RESULTS APPENDIX A. COPY OF WRITTEN COMMENTS B. COPY OF SURVEY RESULTS C. COPY OF ATTENDANCE SHEETS D. PUBLIC MEETING PHOTOS Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS / RECOMMENDATIONS FOR: Texas Dept. Of Transportation (TxDOT), Dallas and Fort Worth Districts Annual Bicycle Public Hearing PURPOSE: To conduct a public hearing on transportation projects and programs that might affect bicycle use, in accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b). PARTNERS: North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) Public Hearing Format The bicycle public hearing agenda is as follows: (1) Open House 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m (2) Welcome and Introductions 6:00 p.m. to 6:10 p.m. (a) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E., TxDOT Dallas District (3) Presentations 6:10 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. (a) State Bike Plan and Programs (i) Teri Kaplan – Statewide Bicycle Coordinator (b) Bicycle Policies and Projects (i) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E. – TxDOT Dallas District (ii) Phillip Hays, P.E. – TxDOT Fort Worth District (c) Regional Bicycle Programs and Projects (i) Karla Weaver, AICP – NCTCOG (4) Open House 7:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Need and Purpose In accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b) , a notice for the opportunity of a public hearing for transportation projects for bicycle use was published in the local newspapers for TxDOT’s Dallas and Fort Worth districts in April 2014. -

CONNECTING the RARITAN HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT Rutgers University Bloustein School of Policy and Planning | Fall 2016 Graduate Studio

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY BIKE SHARE CONNECTING THE RARITAN HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT Rutgers University Bloustein School of Policy and Planning | Fall 2016 Graduate Studio ABOUT THE STUDIO This studio project is an analysis of the health impacts of the We met with Bloustein professors, with planning professionals, potential new Bike Share program planned for the Rutgers-New and with the organizers and staff of bike shares across the coun- Brunswick community. It builds upon our client’s – the Rutgers try in order to ask questions and gain invaluable advice on how University Department of Institutional Planning and Opera- to proceed with our analysis. We used this collected knowledge tion (IPO) – Internal Bicycle Share Proposal. The IPO report to build impact projections and develop a list of actionable rec- highlighted existing bicycle infrastructure, robust public trans- ommendations targeted at maximizing positive health outcomes portation infrastructure, and the high concentration of bicycle while mitigating health concerns. commuters in the study area as support for their proposal. This studio expanded on that analysis by examining the physical, This studio course is intended to advance the goals of Healthier mental, social, and economic health of the users and residents New Brunswick, a network of partners in the City of New Bruns- of Rutgers campus and the surrounding areas. Our targeted wick that are working together to ensure that all residents have audience for this analysis was people who currently do not bike; equal access to the services and conditions that allow for good we paid close attention to equity issues and vulnerable popula- health and well-being. -

Lane Splitting Tips

Sven Miller, Commander Contact: Fran Clader Office of Community Outreach & Media Relations Director of Communications 601 North 7th Street, Sacramento, CA 95811 (916) 843-3310 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 27, 2018 18-27 CHP ANNOUNCES LANE SPLITTING TIPS SACRAMENTO, Calif. – Lane splitting is a privilege enjoyed by California motorcyclists. With this freedom comes a greater responsibility for motorcyclists and drivers to share the road and create a safer highway environment. In 2016, Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr. signed California Assembly Bill 51, which defined motorcycle lane splitting and authorized the California Highway Patrol (CHP) to develop educational safety tips. Through a deliberative process and in consultation with the California Department of Motor Vehicles, the California Department of Transportation, the Office of Traffic Safety, and several motorcycle safety organizations, the CHP has finalized lane splitting tips. “Although lane splitting is legal in California, motorcyclists are encouraged to exercise extreme caution when traveling between lanes of stopped or slow-moving traffic,” said CHP Commissioner Warren Stanley. “Every rider has the ultimate responsibility for their own decision making and safety.” These general safety tips are provided to assist you when riding; however, they are not guaranteed to keep you safe: • Consider the total environment when you are lane splitting (this includes the width of lanes, the size of surrounding vehicles, as well as current roadway, weather, and lighting conditions). • Danger increases at greater speed differentials. • Danger increases as overall speed increases. • It is typically safer to split between the far left lanes than between the other lanes of traffic. • Try to avoid lane splitting next to large vehicles (big rigs, buses, motorhomes, etc.). -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

By the Numbers

By the Numbers Quantifying Some of Our Environmental & Social Work 6.2 MILLION 100 Dollars we donated this fiscal year Percentage of Patagonia products we take to fund environmental work back for recycling 70 MILLION 164,062 Cash and in-kind services we’ve donated since Pounds of Patagonia products recycled our tithing program began in 1985 or upcycled since 2004 741 84 Environmental groups that received Percentage of water saved through our new a Patagonia grant this year denim dyeing technology as compared to environmental + social initiatives conventional synthetic indigo denim dyeing 116,905 Dollars given to nonprofits this year through 100 our Employee Charity Match program Percentage of Traceable Down (traceable to birds that were never live-plucked, 20 MILLION & CHANGE never force-fed) we use in our down products 2 Dollars we’ve allocated to invest in environmentally and socially responsible companies through our 1996 venture capital fund Year we switched to the exclusive use of organically grown cotton 0 8 New investments we made this year through 10,424 $20 Million & Change Hours our employees volunteered this year 1 on the company dime 5 Mega-dams that will not be built on Chile’s Baker 30,000 and Pascua rivers thanks to a worldwide effort Approximate number of Patagonia products 5 in which we participated repaired this year at our Reno Service Center 380 15 MILLION Public screenings this year for DamNation Acres of degraded grassland we hope to restore in the Patagonia region of South America by buying and supporting the purchase of responsibly sourced 75,000 merino wool Signatures collected this year petitioning the Obama administration to remove four dams initiatives social + environmental on the lower Snake River 774,671 Single-driver car-trip miles avoided this year 192 through our Drive-Less program Fair Trade Certified™ styles in the Patagonia line as of fall 2015 100 MILLION Dollars 1% for the Planet® has donated to nonprofit environmental groups cover: Donnie Hedden © 2015 Patagonia, Inc. -

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region The Pennsylvania State University University of Maryland University of Virginia Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University West Virginia University The Pennsylvania State University The Thomas D. Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute Transportation Research Building University Park, PA 16802-4710 Phone: 814-863-1909 Fax: 814-865-3930 1. Report No. VT-2009-05 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6. Performing Organization Code Virginia Tech 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ralph Buehler with Andrea Hamre, Dan Sonenklar, and Paul Goger 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Virginia Tech, Urban Affairs and Planning, , Alexandria Center, 1021 Prince Street, Alexandria, VA 22314 11. Contract or Grant No. DTRT07-G-0003 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered US DOT Final Report, 08/2010-11/2011 Research & Innovative Technology Admin UTC Program, RDT-30 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This report analyzes cycling trends, policies, and commuting in the Washington, DC area. The analysis is divided into two parts. Part 1 focuses on cycling trends and policies in Washington (DC), Alexandria (VA), Arlington County (VA), Fairfax County (VA), Montgomery County (MD), and Prince George’s County (MD) during the last two decades. The goal is to gain a better understanding of variability and determinants of cycling within one metropolitan area. Data on bicycling trends and policies originate from official published documents, unpublished reports, site visits, and in-person, email, or phone interviews with transport planners and experts from municipal governments, regional planning agencies, and bicycling advocacy organizations. -

Bicycle Master Plan: 2012

BICYCLE MASTER PLAN: 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREPARED FOR V VISION STATEMENT VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IX CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION 1 BICYCLING IN MESA 1 THE BENEFITS OF BICYCLING 3 BICYCLE TRIP AND RIDER CHARACTERISTICS 6 BICYCLE USE IN MESA 8 PAST BICYCLE PLANNING EFFORTS 12 REGIONAL PLANNING & COORDINATION EFFORTS 15 WHY MESA NEEDS AN UPDATED BICYCLE PLAN 20 PLAN UPDATE PROCESS AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM 23 CHAPTER 2 - GOALS & OBJECTIVES 25 PURPOSE OF GOALS AND OBJECTIVES 25 GOAL ONE 27 GOAL TWO 28 GOAL THREE 29 GOAL FOUR 30 GOAL FIVE 31 i CHAPTER 3 - EDUCATION, ENCOURAGEMENT, AND ENFORCEMENT 33 INTRODUCTION 33 MESARIDES! 34 EDUCATION 35 ENCOURAGEMENT 38 ENFORCEMENT 42 CHAPTER 4 - BICYCLE FACILITIES AND DESIGN OPTIONS 47 INTRODUCTION 47 BASIC ELEMENTS 48 WAYFINDING 52 BICYCLE PARKING DESIGN STANDARDS 53 BICYCLE ACCESSIBILITY 58 CHAPTER 5 - MESA’S BICYCLE NETWORK 61 INTRODUCTION 61 MESA’S NETWORK OF THE FUTURE 65 DEVELOPING A RECOMMENDED FUTURE NETWORK 68 METHODOLOGY TO IDENTIFY NEEDS 72 ii CHAPTER 6 - IMPLEMENTATION, EVALUATION, AND FUNDING 101 INTRODUCTION 101 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 103 IMPLEMENTATION CRITERIA 104 PROJECT PRIORITY RANKING 105 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROGRAM EXPANSION 122 ADDITIONAL STAFF REQUIREMENTS 124 PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT 125 SUMMARY 130 APPENDIX A - THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN PROCESS 131 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN 131 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM AND COMMUNITY INPUT PROCESS 132 BENEFITS OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) 132 DEVELOPMENT OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) PLAN 133 MESA BICYCLE -

KKKR – Közbringa

KKKR – közbringa Közbringa versus kerékpárkölcsönzés – áttekintés Közbringa Kerékpárkölcsönzés általában speciális kerékpárok szériakerékpárok a városi közlekedés egyik alágazata elsősorban turisztikai céllal felvevő- és leadópont különbözik felvevő- és leadópont azonos ingyenesség vagy kedvező, majd progresszív régiónként eltérő, de mindenképpen magasabb, díjszabás degresszív díjszabás szabályosan felszerelt kerékpárok gyakran hiányosan felszerelt kerékpárok városi/önkormányzati szolgáltatás magánvállalkozás A közbringa rövid története Az első KKKR rendszer Amsterdamban épült ki az 1960-as évek közepén, mely teljességgel bizalmi alapon állt, azaz regisztrációs és díjfizetési kötelezettség nélkül. Ugyanakkor a vonzó feltételek okozták a rendszer bukását is: a számos kerékpárlopás miatt a rendszert néhány hónappal beindítása után fel kellett számolni. Az első sikeres közbringa-rendszert a franciák üzemeltették az 1970-es években, La Rochelle városában. A La Rochelle-i példát a világon számos város vette át az 1990-es években – ekkor volt az első nagy „közbringa-boom” –, igaz, ezek közül sok dőlt be a sorozatos lopások és értelmetlen vandalizmus, vagy éppen a politikai támogatás hiánya miatt. Néhány azonban – így például a Koppenhágában működő ByCyklen (1995) – napjainkig létezik. A második közbringa-hullám a 2000-es évekre tehető: számos európai nagyváros állított fel saját közbringa- hálózatot: az amszterdami központú (és szinte az egész országot lefedő) 2002-es „OV-fiets”; a 2003-ban indult bécsi „Citybike”; a 2003-as berlini „Call a Bike”; a 2007-ben indult párizsi „Vélib’”; vagy éppen a 2010-es londoni „Barcalays Cycle Hire” (avagy közkeletű nevén – Boris Johnson, London polgármestere után elnevezve – a „Boris Bikes”) mind-mind azóta is működő és sikeres hálózatok. Sőt, ami a legfontosabb, a politikai akarat is segíti működésüket. Közbringa-generációk Első generáció: a szabadon vihető Az első generációs közbringa-rendszerek mindenféle megkötés nélkül vehetők igénybe. -

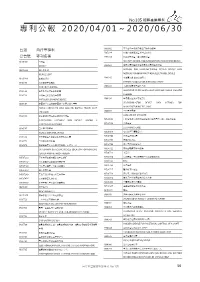

專利公報2020/04/01~2020/06/30

No.105 相關產業專利 專利公報 2020/04 /01 ~ 2020/ 06/ 3 0 台灣 自行車專利 I695802 可供自行車收納之組合式攜帶箱結構 I695924 圓筒鎖之保護裝置及其組裝方法 公告號 專利名稱 I695954 防止犯罪裝置、資訊處理裝置 D205332 自行車 SECURITY DEVICE AND INFORMATION PROCESSING DEVICE BICYCLE I696023 顯示裝置的製造方法及電子裝置的製造方法 D205335 自行車座墊 METHOD FOR MANUFACTURING DISPLAY DEVICE AND BICYCLE SEAT METHOD FOR MANUFACTURING ELECTRONIC DEVICE I696205 可提高安全性的電池模組 D205426 車燈之部分 BATTERY MODULE FOR IMPRVING SAFETY I696558 用於腳踏車的輪轂 HUB FOR A BICYCLE I696223 半導體裝置及其製造方法 I696559 無內胎之自行車輪胎結構 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICE AND MANUFACTURING METHOD THEREOF I696563 自行車之防鎖死煞車機構 I696293 半導體裝置及其製造方法 ANTI-LOCK BRAKING DEVICE SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICE AND METHOD FOR I696564 鎖固結構及具有該鎖固結構的電動自行車架 MANUFACTURING THE SAME FIXING STRUCTURE AND ELECTRIC BICYCLE FRAME WITH I696333 一種直流電機 THE SAME A DC MOTOR-DYNAMO I696566 懸吊總成及具有懸吊總成之自行車 M596556 用於控制顯示裝置之無線控制模組及具方向指示功能之背包 SUSPENSION ASSEMBLY AND BICYCLE HAVING A SUSPENSION ASSEMBLY M596568 升降裝置 ELEVATING DEVICE I696567 自行車控制裝置 BICYCLE CONTROL DEVICE M596644 多功能輕型運動器材 M596706 自行車輻條結構 I696569 用於腳踏車前鏈輪上鏈條的移位裝置 M596707 無聲花轂結構 I696772 自行車用碟煞碟盤 I696978 偵測腳踏車位置以通知伺服器之系統及方法 M596708 自行車花轂離合結構 SYSTEM FOR DETECTING BICYCLE LOCATION FOR NOTICING M596721 前輪自動歸正煞車結構 SERVER AND METHOD THEREOF M596722 水壺架 M597189 用於自行車輪圈組裝之中空鉚釘 M596724 行動裝置之車用安裝配件組及其輔助結構 M597192 自行車輻條切斷與搓牙機結構 M596725 鈴鐺 M597241 自行車或機車之外驅電動機構 M596726 自行車鈴 M597247 自行車前貨架 M596727 整合線式固定座 M597249 具施力控制變速功能之自行車 M596728 自行車之踏踩間距調整結構 M597456 公共腳踏車租借系統 M596872 儲能元件的使用壽命的估算系統 M597488 兩輪車輛停車位自動搜尋裝置 M596883 全電壓萬用型充電器 D205137 攜車架(七) M596950 車輛速度提醒及照相裝置 BIKE CARRIER (7) D204972 輪胎 D205150 -

Determinants of Bicycle Commuting in the Washington, DC Region: the Role of Bicycle Parking, Cyclist Showers, and Free Car Parking at Work

Transportation Research Part D 17 (2012) 525–531 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part D journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trd Determinants of bicycle commuting in the Washington, DC region: The role of bicycle parking, cyclist showers, and free car parking at work Ralph Buehler Urban Affairs and Planning, Virginia Tech, Alexandria Center, 1021 Prince Street, Room 228, Alexandria, VA 22314, USA article info abstract Keywords: This article examines the role of bicycle parking, cyclist showers, free car parking and tran- Bicycling to work sit benefits as determinants of cycling to work. The analysis is based on commute data of Bicycle parking workers in the Washington, DC area. Results of rare events logistic regressions indicate that Car parking bicycle parking and cyclist showers are related to higher levels of bicycle commuting—even Cyclist showers when controlling for other explanatory variables. The odds for cycling to work are greater Trip-end facilities for employees with access to both cyclist showers and bike parking at work compared to those with just bike parking, but no showers at work. Free car parking at work is associated with 70% smaller odds for bike commuting. Employer provided transit commuter benefits appear to be unrelated to bike commuting. Regression coefficients for control variables have expected signs, but not all are statistically significant. Ó 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Over the last decades US cities have increasingly promoted bicycle commuting to reduce local and global air pollution, combat peak hour traffic congestion, and achieve health benefits from physical activity (Alliance for Biking and Walking, 2012).