Journal of Law and Cyber Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRIME-ARY PERSPECTIVE: MAINE, NEVADA, NORTH DAKOTA, SOUTH CAROLINA, and VIRGINIA

PRIME-ARY PERSPECTIVE: MAINE, NEVADA, NORTH DAKOTA, SOUTH CAROLINA, and VIRGINIA PRIME-ARY Perspectives is a series that will give you an overview of the most noteworthy results from each state's primary election, focusing on congressional districts that are likely to be most competitive in November, as well as those that will have new representation in 2019 because of retirements. As always, please do not hesitate to reach out to us with questions! MAINE Yesterday, Maine became the first state in the country to use a "ranked- choice" voting system. The system allows for voters to rank the candidates from favorite to least favorite. If one candidate gets 50% + 1 vote, everything proceeds as usual; if not, vote counters gradually eliminate candidates with fewer votes. As candidates are eliminated, each vote they received goes to the whomever the individual voter chose as their next favorite candidate. This process goes on until there are two candidates and whichever one has the most votes is declared the winner. This process has earned the voting system the alternate moniker of the "instant-runoff" system. The state's deeply unpopular governor, Paul LePage (R), has threatened to refuse to certify the primary results, calling the new system "the most horrific thing in the world." This year, Maine will hold elections for all of its statewide races, one Senate seat, and its 2 seats in the House of Representatives. GUBERNATORIAL Gov. Paul LePage won reelection in 2014, at least partially because an independent candidate won 8.4% of the vote. This election is one of the reasons that the state transitioned to its ranked-voting (as described above). -

US Election Insight 2014

dentons.com US Election Insight 2014 Election results data contained in this report re lect data available as of 8:00 a.m. Eastern Standard Time on November 5, 2014. The boisterous sea of liberty is never without a wave Thomas Jeerson 2014 Election Results The Republican Senate Drought Ends In a Deluge For the past eight years, Republicans sought to reclaim As October closed, polling momentum favored the their Congressional majority, but their eorts to achieve Republicans, and Democrats faced lower than expected election night victory fell short of the mark. Last night, turnout among their base, including African Americans, riding a wave of enthusiasm among their supporters Democratic women, Hispanics and young voters. The and bolstered by voter frustration with the Obama general discontent of many voters toward Congress in administration, Republican candidates across the country general and President Obama in particular meant that delivered victories in virtually every key race. With at least a traditionally Republican-friendly issues like opposition to seven seat gain in the US Senate and an increase of more the Aordable Care Act, national security, the economy, than 10 seats in the US House of Representatives, the 2014 and even the Ebola epidemic in West Africa held sway with election was an unmitigated success for Republicans, voters, who ignored Democratic claims of an improving aording them an opportunity to set the agenda for the economy and the dangers of a Republican congress. last two years of the Obama presidency and setting the This last appeal was notably ineective with women stage for a wide open presidential election in 2016. -

Trump Administration Allies Have Burrowed Into 24 Critical Civil Service Positions and 187 Last-Minute Appointments

Trump Administration Allies Have Burrowed Into 24 Critical Civil Service Positions And 187 Last-Minute Appointments SUMMARY: Following the outgoing administration’s “quiet push to salt federal agencies with Trump loyalists,” an Accountable.US review has found that, as of February 22, 2021, at least 24 Trump administration political appointees have “burrowed” into long-term civil service jobs in the new Biden administration. This includes at least four figures in the national security apparatus, nine figures with environmental regulators, three figures in the Department of Justice, two figures in the embattled Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and at least six other appointees elsewhere who have refused to step down in the transition. Burrowing of this sort is not treated lightly, as officials who transfer from political appointments to career positions must undergo scrutiny by federal personnel overseers for a full five years—and some of these cases have been found to violate federal laws and have drawn congressional scrutiny. However, there is a much wider slate of concerning Trump administration appointments that are not subject to such strict oversight: During the Trump administration’s waning days following the 2020 election, it announced 187 last-minute appointments to various boards, commissions, and councils that don’t require Senate confirmation. While some of these appointments have already drawn alarm for going to campaign staffers, megadonors, and top administration allies, Accountable.US has unearthed even more troubling names in Trump’s outgoing deluge. Similar to how early Trump administration personnel picks were directly conflicted against the offices they served, many of these late Trump appointments are woefully underqualified or have histories directly at odds with the positions to which they were named—and they are likely to stay in long into the Biden administration. -

Senate Section (D)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2018 No. 158 Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro NOMINATION OF BRETT KAVANAUGH called to order by the Honorable CINDY tempore (Mr. HATCH). Mr. MCCONNELL. Madam President, HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the State The senior assistant legislative clerk in the past week and a half, the Amer- of Mississippi. read the following letter: ican people have seen a confusing and chaotic process play out right here in f U.S. SENATE, PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, the Senate. PRAYER Washington, DC, September 25, 2018. They have seen uncorroborated, dec- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Today’s To the Senate: ades-old allegations of wrongdoing pop opening prayer will be offered by Pas- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, up in the press at the last minute, just tor Sam Steele of Chapel by the Sea of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby as Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s confirma- appoint the Honorable CINDY HYDE-SMITH, a from South Padre Island, TX. tion process was winding down. Senator from the State of Mississippi, to per- They have seen an accuser’s request The guest Chaplain offered the fol- form the duties of the Chair. for privacy disregarded and ordinary lowing prayer: ORRIN G. HATCH, standards of fairness completely dis- Good morning. President pro tempore. carded. Christ Jesus sent people out two by Mrs. -

Security and Society in the Information Age Vol. 3

SECURITY Katarzyna MANISZEWSKA, Paulina PIASECKA Editors AND SOCIETY IIt is our pleasure to present a third scholarly volume bringing together a unique series of research papers by talented students – participants in the Security and Society in the Information Age program held at Collegium Civitas University in AGE IN THE INFORMATION Warsaw, Poland. In 2020, due to the pandemic, the program was held for first time online and included a component on the security-related implications of Covid-19. The students took part in a fully-fledged online course followed by an online research internship at the Terrorism Research Center. This book presents the results of their SECUR TY work – research papers devoted to contemporary security threats. The contributors not only analyzed the issues but also looked for solutions and these papers include recommendations for policy makers. We hope you will find this book interesting and valuable and we cordially invite you to learn more about the Security and Society in the Information Age program at: www. AND securityandsociety.org Volume 3 SOCIETY IN THE INFORMATION AGE Volume 3 ISBN 978-83-66386-15-0 9 788366 386150 Volume 3 COLLEGIUM CIVITAS „Security and Society in the Information Age. Volume 3” publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License under the following terms – you must keep this information and credit Collegium Civitas as the holder of the copyrights to this publication. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Reviews: Daniel Boćkowski, PhD, University of Bialystok Marek Jeznach, PhD, an independent security researcher Editors: Katarzyna Maniszewska, PhD ( https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8021-8135) and Paulina Piasecka, PhD ( https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3133-8154) Proofreader: Vanessa Tinker, PhD e-ISBN: 978-83-66386-15-0 ISBN-print: 978-83-66386-16-7 DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.13614143 Publisher: Collegium Civitas Press Palace of Culture and Science, XI floor 00-901 Warsaw, 1 Defilad Square tel. -

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S

Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February 2018 Disclaimer: This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, nor any of their employees makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC, and shall not be used for advertising or product endorsement purposes. LLNL-BOOK-746803 Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue: Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies Zachary S. Davis and Michael Nacht, editors Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February -

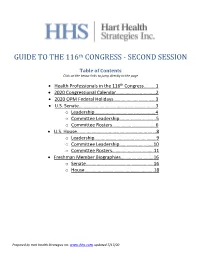

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Petition for Certiorari “When A

No. _______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States INTERNATIONALdREFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT, et al., Petitioners, —v.— DONALD J. TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, et al., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Karen C. Tumlin Omar C. Jadwat Nicholas Espíritu Counsel of Record Melissa S. Keaney Lee Gelernt Esther Sung Hina Shamsi Marielena Hincapié Hugh Handeyside NATIONAL IMMIGRATION Sarah L. Mehta LAW CENTER David Hausman 3450 Wilshire Boulevard, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES #108-62 UNION FOUNDATION Los Angeles, CA 90010 125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 (212) 549-2500 [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioners IRAP, et al. (Counsel continued on inside cover) Justin B. Cox Cecillia D. Wang NATIONAL IMMIGRATION Cody H. Wofsy LAW CENTER Spencer E. Amdur P.O. Box 170208 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES Atlanta, GA 30317 UNION FOUNDATION David Rocah 39 Drumm Street Deborah A. Jeon San Francisco, CA 94111 Sonia Kumar David Cole Nicholas Taichi Steiner Daniel Mach AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES Heather L. Weaver UNION FOUNDATION OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES MARYLAND UNION FOUNDATION 3600 Clipper Mill Road, 915 15th Street NW Suite 350 Washington, DC 20005 Baltimore, MD 21211 Linda Evarts Kathryn Claire Meyer Mariko Hirose INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE ASSISTANCE PROJECT 40 Rector Street, 9th Floor New York, NY 10006 Attorneys for Petitioners IRAP, et al. Johnathan Smith Mark H. Lynch Sirine Shebaya Mark W. Mosier MUSLIM ADVOCATES Herbert L. Fenster P.O. Box 66408 Jose E. Arvelo Washington, D.C. 20035 John W. Sorrenti Katherine E. Cahoy Richard B. -

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law About the Brennan Center for Justice

B R E N N A N CENTER FOR JUSTICE VOTING LAW CHANGES IN 2012 Wendy R. Weiser and Lawrence Norden Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law about the brennan center for justice The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on the fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to campaign finance reform, from racial justice in criminal law to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. About the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program The Brennan Center’s Democracy Program works to repair the broken systems of American democracy. We encourage broad citizen participation by promoting voting and campaign reform. We work to secure fair courts and to advance a First Amendment jurisprudence that puts the right of citizens—not special interests—at the center of our democracy. We collaborate with grassroots groups, advocacy organizations, and government officials to eliminate the obstacles to an effective democracy. acknowledgements The Brennan Center gratefully acknowledges the Bauman Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Democracy Alliance Partners, Ford Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, The Irving B. Harris Foundation, Mitchell Kapor Foundation, Michael Kieschnick, Nancy Meyer and Marc Weiss, Open Society Foundations, Rockefeller Family Fund, Tides Advocacy Fund, and Wallace Global Fund for their generous support of our voting work. -

Chapter I—Members of the Nevada Legislature

LegisLative ManuaL CHAPTER I MEMBERS OF THE NEVADA LEGISLATURE LegisLative ManuaL BIOGRAPHIES OF MEMBERS OF THE NEVADA SENATE LEGISLATIVE BIOGRAPHY — 2011 SESSION LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR AND PRESIDENT OF THE SENATE BRIAN K. KROLICKI Republican Born: 1960 – Warwick, Rhode Island Educated: Stanford University, B.A., Political Science Married: Kelly Krolicki Children: Katherine, Caroline, Elizabeth LEGISLATIVE SERVICE: First elected Lieutenant Governor, November 2006, reelected November 2010; President of the Senate, 2007-2011—four special and three regular sessions. AFFILIATIONS: Chair, Reno-Tahoe Winter Games Coalition, 2007-present; Aspen-Rodel Public Leadership Fellowship, 2007-present; Board, United States Intergovernmental Policy Advisory Committee on Trade, 2003-present; Nevada Renewable Energy Transmission Access Advisory Committee (Phase II), 2008-2009; State Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation Task Force, 2007-2009; Board, Desert Research Institute, 1999-2005; Board, Lake Tahoe Community College Foundation, 1998-2005; Governing Board, Davidson Academy. PERSONAL AND PROFESSIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS: Parkway Alumni Association Hall of Fame, Member of Charter Class; Board/Treasurer/Secretary, American Cancer Society, Southwestern United States Division; Board, American Cancer Society, Nevada Division, 1994-1997; Vice Chair, Planning Commission, Douglas County, 1991-1998; Gritz Award for Excellence in Public Finance, 2004; Unruh Award as the Nation’s Most Outstanding State Treasurer, 2004; President, National Association of State Treasurers -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP, 45th President of the United States; born in Queens, NY, June 14, 1946; graduated from New York Military Academy in Cornwall, NY, in 1964; received a bachelor of science degree in economics in 1968 from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA; joined Trump Management Company in 1968; became president of the Trump Organization in 1971 until 2016, when elected President of the United States; family: married to Melania; five children: Donald Jr., Ivanka, Eric, Tiffany, and Barron; nine grandchildren; elected as President of the United States on November 8, 2016, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2017. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Donald J. Trump. Deputy Assistant to the President and Director of Oval Office Operations.—Jordan Karem. Executive Assistant to the President.—Madeleine Westerhout. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Mike Pence. Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Nick Ayers. Assistant to the President and National Security Advisor to the Vice President.—Keith Kellogg. Deputy Assistants to the President and Deputy Chiefs of Staff to the Vice President: Jarrod Agen, John Horne. Deputy Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff to Mrs. Karen Pence.—Jana Toner. Deputy Assistant to the President and Domestic Policy Director to the Vice President.— Steve Pinkos. -

The International Code Council Strongly Supports the Nomination of Building Safety Advocate Peter Feldman to the Consumer Product Safety Commission

June 14, 2018 The International Code Council strongly supports the nomination of building safety advocate Peter Feldman to the Consumer Product Safety Commission Earlier this month, the President nominated Peter A. Feldman to be a commissioner of the Consumer Product Safety Commission for the remainder of a seven-year term expiring October 16, 2019. Feldman is a long-time advocate of building safety and has dedicated his career to protecting the health and safety of the public. In 2007, Feldman worked at the International Code Council, where he supported the Code Council’s mission to provide up-to-date, modern building, fire, safety codes and standards for the protection of people and the built environment. He drafted and advocated for passage of the Building Code Administration Act of 2007, a bill supporting local building code enforcement departments to increase staffing, provide staff training, support professional individual certification or departmental accreditation. Since his time at the Code Council, Feldman has continued to support public safety with a focus on consumer protection and product safety. As indicated in his nomination announcement from the White House: Mr. Feldman is senior counsel to the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, advising on consumer protection, product safety, data, and privacy issues under the leadership of Chairman John Thune of South Dakota. Mr. Feldman has played a key role in the development and enactment of major consumer protection legislation, committee investigations, and congressional oversight of federal agencies, including the Consumer Product Safety Commission. He previously served on the legislative staff of Senator Mike DeWine of Ohio, where he worked directly on the Virginia Graeme Baker Pool and Spa Safety Act, a landmark safety bill that remains in effect today.