Zillion-To-One Shot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support for the Implementation of the National Sustainable Tourism Master Plan (NSTMP) BL-T1054

Destination Development Plan & Small Scale Investment Project Plan Specific Focus on the Toledo District, Belize 2016 - 2020 Prepared for: Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Table of Tables.............................................................................................................................................. 5 Table of Annexes .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Glossary: ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary: ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Background: ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Community Engagement: .................................................................................................................. -

Sapodilla Cayes Management Plan 2011-2016

Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve Management Plan 2011 – 2016 A component of Belize’s World Heritage Site SEA Belize National Office Placencia Village Stann Creek District Belize, Central America Phone: 501-523-3377 Fax: 501-523-3395 [email protected] Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve We would like to thank the Board members, programme managers and staff of the Southern Environmental Association, and more specifically of the Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve, for their participation and input into this management plan. Special thanks also go Isaias Majil (Fisheries Department), and to all stakeholders who participated in the workshops and meetings of the management planning process – particularly the tour guides and fishermen of Punta Gorda, who provided important input into the planning. A number of other people also provided technical input outside of the planning meetings and forums – particular thanks go to Melanie McField, Rachel Graham, Burton Shank, Adele Catzim and Guiseppe di Carlo, Lee Jones, Bert Frenz, John Tschirky, Russel, Vincente, Mrs. Garbutt, Armando, ReefCI, Adele Catzim and Guiseppe di Carlo. We would also like to thank Jocelyn Rae Finch and Timothy Smith for all their assistance in the preparation of the management plan, to Adam Lloyd (GIS Officer, Wildtracks) for the mapping input, and to Hilary Lohmann (Wildtracks) for editing assistance. We also appreciate the input into the previous draft management plan by Jack Nightingale in 2004, which provided much of the historical perspective for this plan. Financial support towards this management planning process was provided by NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Prepared By: Wildtracks, Belize [email protected] Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve – Management Plan 2011-2016 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

Caddy IASCP Paper 1 Adaptation, Conflict and Compromise In

Adaptation, Conflict and Compromise in Indigenous Protected Areas Management Common property theory has increasingly broadened its scope from an initial focus on community-level systems, to recognition and examination of how these continuously interact and evolve in response to external dynamics, constraints and multi-level partnerships. The common property systems of indigenous peoples are clearly not static and brittle institutions, but have survived to the present day precisely because of their propensity towards adaptation. As indigenous peoples confront new challenges in a globalizing world, the co- management model for protected areas governance - parks which often encompass significant tracts of their traditional lands - has presented itself as an opportunity for safeguarding common property interests. In practice, indigenous peoples have enjoyed varying degrees of success in meeting these goals through protected area partnerships with the conservation sector, as will be illustrated through case studies drawn from southern Belize. The Government of Belize (GoB) has shown itself unusually willing to assign protected area status to an extremely large percentage of its national territory. However, expectations that the national protected areas system would be instrumental in fuelling development in Belize were tempered by subsequent reality. The GoB has in practice failed to secure sufficient funds to effectively manage its protected areas, let alone generate income and profit from their existence. In light of this situation, various -

Coral Reef Management in Belize: an Approach Through Integrated Coastal Zone Management

Ocean & Coastal Management 39 (1998) 229Ð244 Coral reef management in Belize: an approach through Integrated Coastal Zone Management J. Gibson!,*, M. McField", S. Wells# ! GEF/UNDP Coastal Zone Management Project, P.O. Box 1884, Belize City, Belize " Department of Marine Science, University of South Florida, 140 Seventh Ave. South, St Petersburg, FL 33701, USA # WWF International, Ave du Mont Blanc, 1196 Gland, Switzerland Abstract Belize has one of the most extensive reef ecosystems in the Western Hemisphere, comprising one of the largest barrier reefs in the world, three atolls and a complex network of inshore reefs. Until recently, the main impacts were probably from natural events such as hurricanes. However, anthropogenic threats such as sedimentation, agrochemical run-o¤, coastal develop- ment, tourism and overfishing are now of concern. To limit these impacts, Belize is taking the approach of integrated coastal zone management. The programme is building on the existing legislative framework and involves the development of an appropriate institutional structure to co-ordinate management activities in the coastal zone. A Coastal Zone Management Plan is being prepared, which will include many measures that will directly benefit the reefs: a zoning scheme for the coastal zone, incorporating protected areas; legislation and policy guidelines; research and monitoring programmes; education and public awareness campaigns; measures for community participation; and a financial sustainability mechanism. ( 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction The Belize Barrier Reef is renowned as the largest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. Nearly 260 km long, it runs from the northern border of the country, where it is only about 1 km o¤shore, south to the Sapodilla Cayes which lie some 40 km o¤shore. -

310 INDE X See Also Separate Greendex P316. A

© Lonely Planet Publications 310 INDEX Index See also separate GreenDex p316. Arvigo, Rosita 63, 207, 209 Benque Viejo del Carmen 208-11 ABBREVIATIONS ATMs 287 Benque Viejo del Carmen Fiesta 209 A ACT Australian Capital Ayala, Carlos 146 Benque Viejo House of Culture 208 Territory accommodations 279-80, 281, see Be Pukte Cultural Center 202 NSW New South Wales also individual locations B bicycling 48, 129, 147-8, 278, 294 NT Northern Territory activities 69-82, see also individual Bacalar Chico National Park & Marine Big Drop Falls 229 Qld Queensland activities Reserve 126 Big Rock Falls 212 SA South Australia Actun Tunichil Muknal 191-2 Baldy Beacon 212 Bio-Itzá 278 Tas Tasmania Aguacaliente Wildlife Sanctuary 252 Balick, Dr Michael 209 Bio-Itzá Reserve 278 Vic Victoria air travel Banquitas House of Culture 164 Biotopo Cerro Cahuí 269 WA Western Australia air fares 292, 294 Baron Bliss Day 98, 99 Bird Caye 117 airlines 291 Baron Bliss Tomb 95 birds 61-2, see also bird-watching airports 291 Baron Bliss Trust 98 bird-watching 60, 61-2, 81, 148-9 carbon offset schemes 295 barracudas 61, 76, 74, 132, 227, see Belize District 110, 114, 116, 117 to/from Belize 291-2 also fishing Cayo District 179, 186, 187, 192, within Belize 294 Barranco 254-5 193, 194, 200, 204, 208, 210 Altun Ha 106-7, 107, 14-15 Barton Creek Cave 193 Guatemala 278 Ambergris Caye 123-41, 124, 127 basketball 48 northern cayes 147-8, 158 accommodations 132-6 Baymen 32-4 Orange Walk District 169, 171 activities 126-9 beer 85 Stann Creek District 228, 234, attractions 126 Belize -

State of the Belize Coastal Zone Report 2003–2013

Cite as: Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute (CZMAI). 2014. State of the Belize Coastal Zone Report 2003–2013. Cover Photo: Copyright Tony Rath / www.tonyrath.com All Rights Reserved Watermark Photos: Nicole Auil Gomez The reproduction of the publication for educational and sourcing purposes is authorized, with the recognition of intellectual property rights of the authors. Reproduction for commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. State of the Belize Coastal Zone 2003–2013 2 Coastal Zone Management Authority & Institute, 2014 Table of Contents Foreword by Honourable Lisel Alamilla, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development ........................................................................................................................................................... 5 Foreword by Mr. Vincent Gillett, CEO, CZMAI ............................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................................. 7 Contributors ............................................................................................................................................................ 8 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Belize to Tikal Reefs, Rivers & Ruins of the Maya World

BELIZE TO TIKAL REEFS, RIVERS & RUINS OF THE MAYA WORLD MARCH 10-18, 2018 | ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC QUEST DEAR DUKE ALUMNI AND FRIENDS, The breadth of biodiversity found in the waters and jungles of Belize and Guatemala is nothing less than astounding. From the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, the largest reef in the Northern Hemisphere and the third largest in the world, to the lush jungles of the Maya Biosphere Reserve, an impressive array of wildlife calls these ecosystems home. And over the course of this nine-day expedition, you’ll have the opportunity to observe and photograph many of them up close. Traveling aboard the only expedition ship exploring the Mesoamerican Reef gives you access to places few ever get to see. And the ship’s tools let you experience these diverse habitats with all your senses. Snorkel or dive in warm tropical waters over this extensive reef that is home to hundreds of species of fish and more than 90 species of coral. Seek solitude, or a little exercise, as you kayak and stand-up paddleboard on turquoise lagoons. Then head ashore on Zodiacs to white sand beaches for naturalist-led hikes in search of nesting red- footed boobies. The region also holds a fascinating human history—adding another compelling facet to this compact yet comprehensive expedition. In the sublime Maya ruins of Tikal, you’ll spend a full day and a half exploring the stone temples, palaces, and public spaces. Plus, venture to lesser-visited sites like Topoxté and Quiriguá, providing you with rich insight into this once great civilization. -

Chapter Five: TIDE and the Maya Mountain Marine Transect

Chapter Five: TIDE and the Maya Mountain Marine Transect What’s unique about the [transect] is the interchange between the reef, the estuaries and the rivers; it’s a water-based ecological system. So the ecology leads to social organization. – Peter Esselman (2002) Marketing is everything. We are looking for something sexy. You need a sexy name that will sell quickly. I like the Maya Mountain Marine Corridor. It’s marine, it’s the Maya Mountains and it’s in a corridor. It sells the ridges to reef concept. – Wil Maheia (2002) Introduction The Maya Mountain Marine Area Transect (MMMAT)19 concept was first developed by a Belizean environmental research non-governmental organization (NGO), with funding and technical support from The Nature Conservancy (TNC). The MMMAT represents an effort to confront the challenges posed by expanding development in Southern Belize. This case study will look at the three coastal and marine protected areas within the MMMAT, and analyze the potential value of the MMMAT concept as a forum for promoting multi- stakeholder discussions and coordination in light of the events that have taken place over the past decade. Background The MMMAT as an ecological system The MMMAT was defined as a conceptual land management unit by the Belize Center for Environmental Studies (BCES)20 and TNC in the mid-1990s that would protect biodiversity and natural ecosystem functions in the Toledo District through a corridor of public and private protected areas (TIDE 1998:6) (see Map 5, p.39). The conceptual million-acre corridor area is comprised of six large watersheds that empty into Port Honduras: Monkey Chapter Five 91 TIDE and the MMMAT River, Payne’s Creek, Deep River, Golden Stream, Middle River, and Rio Grande watersheds (TIDE 2000:6-7) (see Map 4, p.38). -

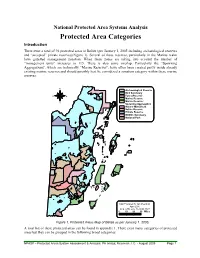

Protected Areas Analysis

National Protected Area Systems Analysis Protected Area Categories Introduction There exist a total of 94 protected areas in Belize (per January 1, 2005 including archaeological reserves and “accepted” private reserves)(Figure 1). Several of these reserves, particularly in the Marine realm have gazetted management zonation. When these zones are taking into account the number of “management units” increases to 115. There is also some overlap. Particularly the “Spawning Aggregations”, which are technically “Marine Reserves”, have often been created partly inside already existing marine reserves and should possibly best be considered a zonation category within these marine reserves. N Archaeological Reserve Bird Sanctuary W E Forest Reserve Marine Reserve Marine Reserve: S Spawning Aggregation Natural Monument Nature Reserve Private Reserve Wildlife Sanctuary National Park MapPreparedbyJanMeerman April 2005 Grid: UTM zone 16, NAD 1927 0102030Miles Figure 1. Protected Areas Map of Belize as per January 1, 2005. A total list of these protected areas can be found in appendix 1. There exist many categories of protected areas but they can be grouped in the following broad categories: NPASP – Protected Areas System Assessment & Analysis: PA analys; Meerman J. C. - August 2005 Page 1 Bird Sanctuaries N Doubloon Bank W E S Los Salones Little Guana Caye Bird Caye Un-Named Man of War Caye Monkey Caye Map prepared by Jan Meerman January 2005 Grid: UTM zone 16 Datum: NAD 1927 Central America 010203040Miles Figure2. Bird Sanctuaries The 7 Bird Sanctuaries are some of the oldest protected areas (Crown Reserves) that have biodiversity conservation in mind. They were gazetted in 1977 for the protection of waterfowl nesting and roosting colonies. -

The Voice of the Fishermen of Southern Belize

he Voice oftheFishermenSouthernBelize he Voice The Voice of the Fishermen of Southern Belize A Publication by TIDE & TRIGOH Edited by Will Heyman y Rachel Graham TIDE &TRIGOH The Voice of the Fishermen of Southern Belize A publication of the Toledo Institute for Development and Environment and The Trinational Alliance for the Conservation of the Gulf of Honduras Edited by Will Heyman and Rachel Graham PROGRAMA AMBIENTAL REGIONAL PARA CENTRO AMERICA The Voice of the Fishermen of Southern Belize 3 Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE) The Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE) is a non-government orga- nization (NGO) committed to promoting integrated conservation and development in South- ern Belize. TIDE recognizes that local communities are dependent on natural resources so that conservation and wise utilization of natural resources will sustain both cultures and the environment. TIDE is also one of nine members of the Tri-National Alliance of NGOs for the Conservation of the Gulf of Honduras (TRIGOH), and shares a goal of regional fisheries management. TIDE Wil Maheia Director, TIDE PO Box 150 Punta Gorda, Belize, Central America Tel : +501 7 22274 Fax : +501 7 22274 Email : [email protected] Web: http://www.belizeecotours.org Document date : September 2000 4 The Voice of the Fishermen of Southern Belize Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................iv Executive Summary ..........................................................................................v -

Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System- Model to Cope with Climate Change

BELIZE BARRIER REEF RESERVE SYSTEM- MODEL TO COPE WITH CLIMATE CHANGE Beverly Wade Ministry of Blue Economy and Civil Aviation- BELIZE Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System Cluster Site: Bacalar Chico National Park and Marine Reserve- 11,399 ha Glover’s Reef Marine Reserve- 35,067 ha South Water Caye Marine Reserve- 47,700 ha Sapodilla Cayes Marine Reserve- 15,619 ha Laughing Bird Caye National Park- 4,095 ha Blue Hole Natural Monument- 414 ha Halfmoon Caye National Monument- 3,954 ha Key Accomplishments: Fisheries Resources Act; National Fisheries Policy, Strategy and Action Plan Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan and Regional guidelines; currently being updated. Parrotfish ban since 2009; improved coral health over last decade (currently highest reef health score in the region) National Rollout of Manage Access Adaptive Management Plans- Lobster and Conch Expansion of marine reserve network (increase areas under protective status; proposed expansion of replenishment zones up to 10% of territorial waters Update of the Mangrove regulations and the Environmental Impact Assessment regulations Moratorium- Offshore Oil Exploration Promoting value added products, improving efficiency within the supply and value chains and seeking higher value markets for the fisheries sector Coral Restoration Addressing invasive species Desired State of Conservation -2016 Assistance from: • UNESCO World Heritage Programme • IUCN • Key National Stakeholders BBRRS removed from WH “in Danger” List in 2018; mangrove reserves pending Desired State of Conservation -2016 The Resilient Reefs Initiative is committed to Resilient working with each site to develop a Reefs resilience strategy that directly responds to Initiative the site’s core challenges, and integrates resilience into the site’s management processes.