Managing Values of the Pastoral Landscapes on the East Coast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Birdlife in Gisborne District: Application of the River Values Assessment System

Native birdlife in Gisborne District: Application of the river values assessment system (RiVAS and RiVAS+) Sandy Bull Andy Bassett Ken F.D. Hughey LEaP Research Paper No. 5 March 2012 Native Birdlife in Gisborne District: Application of the river values assessment system (RiVAS and RiVAS+) Sandy Bull Andy Bassett Ken F.D. Hughey Land Environment and People Research Paper No. 5 March 2012 ISSN 2230-4207 (online) ISBN 978-0-86476-292-4 (online) Lincoln University, Canterbury, New Zealand Native Birdlife in Gisborne District Acknowledgements This work was mostly funded by the Ministry of Science and Information as part of the Envirolink grant 1012-GSDC92: Significance assessment of river uses & values – Gisborne’ – we thank the Ministry and also GDC (in particular Jo Callis) for their support. ©LEaP, Lincoln University, New Zealand 2012 To contact LEaP please use the following electronic addresses Contacts email: [email protected] web: http://www.lincoln.ac.nz/leap This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without restriction, provided LEaP, Lincoln University is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of LEaP, Lincoln University, New Zealand. Series URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10182/3410 i Native Birdlife in Gisborne District Executive Summary The River Values Assessment System (RiVAS and RiVAS+) was applied to the native birdlife value in Gisborne District. The method was applied to differentiate native fish sites of national significance from those of regional significance or local significance. Of 19 rivers or river segments evaluated one was considered of regional significance, namely the Lower Waiapu; the remainder are of local significance. -

G11 Schedule

Gisborne District Council Tairawhiti Resource Management Plan G11 Schedule TERRESTRIAL AREAS OF SIGNIFICANT CONSERVATION VALUE TABLE OF CONTENTS WP12 ........................................................................................................ 32 PR14 .......................................................................................................... 1 WR36 ........................................................................................................ 33 PR36 .......................................................................................................... 2 WR37 ........................................................................................................ 34 PR29 .......................................................................................................... 3 WR38 ........................................................................................................ 35 PR10 .......................................................................................................... 4 WR49 ........................................................................................................ 35 PP0 ............................................................................................................. 5 WR55 ........................................................................................................ 36 PR20 .......................................................................................................... 6 WR56 ....................................................................................................... -

Tairāwhiti 2050 Shaping the Future of Our Region

Te Kaunihera o Te Tairāwhiti Gisborne District Council TAIRĀWHITI 2050 SHAPING THE FUTURE OF OUR REGION TAIRĀWHITI REGIONAL SPATIAL PLAN Adopted by Gisborne District Council 2020 MŌ TĒNEI MĀHERE ABOUT THIS PLAN WHAT IS TAIRĀWHITI 2050 Tairāwhiti 2050 is Gisborne District Council’s vision for the region for the next 30 years. We call this our “spatial plan”, which is a document that: • states our region’s major challenges and how we’ll tackle them. • outlines our shared aspirations for our region’s future wellbeing and what we expect to achieve by 2050. • aligns the strategies and plans of Council, government agencies and other organisations to enable collaboration. • sets direction for regional planning and development, decision-making and investments. • maps out where critical infrastructure, transport connections and development will occur and where there are constraints. WHY WE NEED A SPATIAL PLAN The challenges and opportunities facing those who call Tairāwhiti home are complex and interconnected. How we as a community, plan and respond over the next 30 years will make a significant difference to future generations. Tairāwhiti does not have a stand-alone document that provides a clear and shared vision about what we want our region to look like in the future. Tairāwhiti 2050 therefore considers the current economic, social, environmental, physical and cultural trends so that integrated solutions are found to address the various challenges and opportunities for growth and change. No single organisation can respond alone, so region-wide collaboration is required. Together with communities and agencies we’ve created this plan to provide strategic direction in a way that considers social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing. -

MONDAY, JULY 12, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PM PRESSURE on COVID SWEEPING THROUGH FIJI WEARABLE PRODUCERS PAGE 14 ART WONDER PAGE 2 PAGE 6 Waikohu, Again

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI MONDAY, JULY 12, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PM PRESSURE ON COVID SWEEPING THROUGH FIJI WEARABLE PRODUCERS PAGE 14 ART WONDER PAGE 2 PAGE 6 Waikohu, again AFTER-MATCH JUBILATION: Waikohu won the Lee Bros Shield in a tense final at Rugby Park on Saturday, cementing the club’s dominance as the top team in the region. It is the club’s third win of the district’s premier rugby trophy in four years. They defeated OBM 19-5. More pictures page 5, match report back page. Picture by Paul Rickard ‘Empty seat’ since 2019 Urgency around need to appoint Indigenous Rights Commissioner by Alice Angeloni is a bad idea. What they’re saying is they One Race Relations Commissioner The Human Rights Act legislates for a don’t have the money. responsible for all ethnic minority chief commissioner and up to four others. AOTEAROA’S first and last Indigenous “It’s extremely communities and tangata whenua was The Act specifies three “priority areas” Rights Commissioner wants the role disappointing.” “out of date”, he said. that must be led by a commissioner reinstated. Hunt said the “It reflects our understanding of New — disability rights, equal employment Former commissioner Karen Johansen appointment of an Zealand in the 1960s and ’70s.” opportunities and race relations. (Rongowhakaata) advocated for the Indigenous Rights Hunt said it was not a criticism of Race Hunt understood the Act was human rights of tangata whenua between Commissioner was Relations Commissioner, former Gisborne changed in 2017 to replace part-time 2008 and 2017. -

Gisborne Wastewater Network - Overflow Discharges

Gisborne Wastewater Network - Overflow Discharges Resource Consent Application and Assessment of Effects on the Environment For Gisborne District Council Community Lifelines June 2019 REPORT INFORMATION AND QUALITY CONTROL Prepared for: Wolfgang Kanz 4 Waters Strategy Advisor, Lifelines Gisborne District Council Author: Megan Dever Senior Planning and Policy Consultant Author: Ian Mayhew Principal Planning and Policy Consultant Reviewer: Megan Dever Senior Planning and Policy Consultant Approved for Ian Mayhew Release: Principal Planning and Policy Consultant Document Name: AA2372_GDC Wastewater Overflows_Application and AEE_Final Version History: Final 17 June 2020 CONTENTS Page GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS AND ACRONYMS ......................................................................................... VI 1 APPLICATION – INTRODUCTION AND SCOPE ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Wet Weather Overflows..............................................................................................................1 1.3 Dry Weather Overflows ...............................................................................................................2 1.4 Overflow Reduction and Mitigation ............................................................................................2 1.5 Scope of Application ....................................................................................................................4 -

The Role of Mass-Movement in Shore Platform Development Along the Gisborne Coastline, New Zealand

EARTH SCIENCE JOURNAL Vol. 2, No. 1, 1968 THE ROLE OF MASS-MOVEMENT IN SHORE PLATFORM DEVELOPMENT ALONG THE GISBORNE COASTLINE, NEW ZEALAND R. F. McLEAN University of Canterbury Christchurch C. F. DAVIDSON Karamu High School Hastings Abstract Tidal shore platforms form a conspicuous part of the coastal scenery north of Gisborne, New Zealand. Some of these platfoI1l1s are being extended landward under present-day conditions. Present widening results primarily from cliff-retreat by mass-movement. The coincidence in distribution of areas of wave convergence, mass-movement and shore platforms suggests a genetic connection between these marine and subaerial process and response elements. Various types of mass-movement are involved in cliff-retreat, notably slumps, flows, debris slides and soil and rock falls. While the products of such mass-movement forms are removed by wave action, extensive boulder fields on some shore platforms indicate that removal is not always complete. Not all of the shore platforms on this coast are being widened at present. Widening has ceased where active mass-movement is not occurring. INTRODUCTION Shore platforms are distinctive features of many erosional coastlines. They have been reported from many parts of the world and the English literature alone includes many papers about their description, formation and geomorphic interpreta- ation. Significant contributions to this literature have ~n made by workers around the Pacific region including California (Eniery~ " 1946; Shepard and Grant. 1947), Hawaii (Stearns, 1935), Japan (Mii. 1962), Australia (Jutson, 1939, 1940, 1950, 1954; Bird and Dent, 1966), and New Zealand (Bartrum, 1916, 1926, 1935. 1938; Gill, 1950; Wright, 1967). -

The Turanganui River

The Turanganui River A Brief History OCTOBER 2006 Michael Spedding The Turanganui River A Brief History by Michael Spedding OCTOBER 2006 © Copyright 2006, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN:0-478-14120-3 Published by Department of Conservation PO Box 668 Gisborne, New Zealand in association with NZ Historic Places Trust, Tairawhiti Museum and Eastland Port Co. Ltd CONTENTS Foreword 5 Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 A Contested Site 7 A Heritage Landscape 8 National Identity 9 The River 10 Original Physical Features 10 Physical Modifications 11 Heritage Description 13 Introduction 13 Tangata Whenua 13 First Arrivals 13 Early Inhabitants 15 Arrival of James Cook 17 Maori Settlement on The River 21 From River to Port 23 Turanga to Gisborne 26 Growth of The Port 28 The Cook Landing Site 29 Research Findings 30 Recent Archaeological Findings 30 Weddel Kaiti Freezing Works Site 30 Heinz-Wattie Site 30 Moa Bone and Footprints 31 Location of Te Toka A Taiau 31 Heritage Significance 32 Historical 32 Cultural - A Customary Perspective 33 Summary 37 Conclusion 39 Further Reading 40 2 “The foreshore of the Turanganui River is one of the world’s great voyaging sites. It is the landing place of the Horouta canoe, celebrating the achievements of the Polynesian star navigators. It is the place where Captain James Cook and his companions first came ashore in New Zealand, heralding the traditions of European exploration and discovery. It is the site where Tupaea, the Ra’iatean high priest navigator who sailed with Cook, first met Maori, marking the links between local people and their ancestral homelands. -

Tuesday, July 6, 2021

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, JULY 6, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 3 PAGE 18 BABIES FIGHTING MAKING UK COMING DO AFTER OUT OF FOR BREATH POOLS LOCKDOWN CLOSURE PAGE 15 SHIP BACKLOG QUEUEING UP: Several log ships wait to load up at Eastland Port yesterday. About a dozen ships were visible this morning. The number either in port or at anchor is actually 14, whch has been described as the biggest build-up of ships at anchor off Gisborne since World War 1. It has been reported that idle ships cost owners $35,000 a day. Picture by Liam Clayton A fleet of ships are waiting in and Biggest build-up since WW1 beyond Turanganui- a-Kiwa/Poverty Bay. by Murray Robertson Log exports were resumed at and we will continue to Computer software the weekend when heavy seas collaborate on more initiatives (right) which tracks a THE build-up of log ships subsided. and efficiencies to ease the ship’s location from anchored off Gisborne continues The logger Taikoo Brilliance pressure on the forestry its positional radio as Eastland Port catches up was loaded over the weekend industry. signals shows one is on a backlog of exports caused and sailed early yesterday “This situation also highlights in port, two are in the by heavy swells and restricted afternoon. Within an hour, the importance of the Twin inner bay and the rest access during wharf repairs. another ship, the AC Kathryn, Berth Project, which will help are further out. In port About a dozen log ships were was brought in and docked to future-proof the port. -

210901GH.Pdf

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 INVESTIGATING LOG ‘WE’RE NOT BIDEN SHIP INCIDENT PAGE 3 UNDER OUT OF THE FIRE OVER WOODS YET’ US EXIT PAGE 6 PAGE 13 THAT’S GOOD COFFEE: Brother and sister Chris and Sheryl Parkinson enjoy their morning coffee fix outside Raglan Roast. Right, the steadily growing queue of cars at McDonald’s. Pictures by Liam Clayton (above) and Ben Cowper GISBORNE was noticeably busier this morning as the country south of Auckland dropped from Alert Level 4 to 3 as of midnight. And the most popular places were, of course, takeaway and coffee outlets trading under the Level 3 contactless guidelines. The queue of cars at McDonald’s this morning steadily grew, with at least one blissfully happy KA KITE 4, customer spotted cramming a handful of fries into his gob as he was driven away. Coffee lovers were out in force for their morning fix, including brother and sister Chris and Sheryl Parkinson, who were clearly in caffeine heaven after their Raglan Roast hits. Surfers hanging out for a wave got the green light and about 10 were out in the water at The Pipe break this morning. Nearby Poverty Bay Golf Club reopened its KIA ORA 3 fairways, as did fellow city club Electrinet Park, with both following NZ Golf guidelines under Level 3. People are reminded that the new alert level still comes with many regulations of Level 4. Riding the wave into new alert level SEE PAGES 3 AND 7 BACK ON BOARD: About 10 surfers hit the waves at the city’s Pipe break this morning after the region moved into Covid-19 Alert Level 3. -

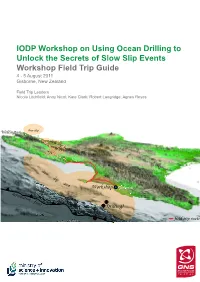

Overview of Hikurangi Margin Slow Slip Event, Gisborne (2-Days Field Trip)

IODP Workshop on Using Ocean Drilling to Unlock the Secrets of Slow Slip Events Workshop Field Trip Guide 4 - 5 August 2011 Gisborne, New Zealand Field Trip Leaders Nicola Litchfield; Andy Nicol; Kate Clark; Robert Langridge; Agnes Reyes Wellington slow slip slow slip Napier slow slip area Workshop Gisborne deformation front Drilling? field trip route BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Litchfield, N.; Nicol, A.; Clark, K.; Langridge, R.; Reyes, A.; Wallace, L.M.; Mountjoy, J.J. 2011. IODP Workshop on Using Ocean Drilling to Unlock the Secrets of Slow Slip Events: Workshop Fieldtrip Guide. GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 40. 73p. Nicola Litchfield, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Andy Nicol, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Kate Clark, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Robert Langridge, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Agnes Reyes, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Laura Wallace, GNS Science, PO Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Joshu Mountjoy, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Wellington © Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited, 2011 ISSN 1177-2441 ISBN 978-0-478-19848-5 CONTENTS HEALTH AND SAFETY ISSUES .......................................................................................... V DAY 1 FIELD TRIP SCHEDULE ......................................................................................... VII DAY 2 FIELD TRIP SCHEDULE ........................................................................................ VIII INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL -

50992 Open Space 69.Indd

$5.00 ™ $&-"5*/( MAGAZINE OF THE QUEEN ELIZABETH II NATIONAL TRUST No.69, April 2007 :&"34 30th anniversary celebration • Focus on East Coast/Gisborne Helping you protect the special nature of your land QEII helps landowners protect significant natural and cultural Regional Representatives features on their land. Far North Features protected include: Greg Blunden Tel: 09 407 5243 • Landscapes • Forests and/or bush remnants Kaipara Nick Matich Tel: 09 439 8932 • Wetlands • Tussock grasslands Whangarei • Cultural sites • Streams Nan Pullman Tel/Fax: 09 434 3457 • Coastlines • Geological features Northwest Auckland Rodney Straka Tel: 09 420 4082 • Archaeological sites • Wildlife habitats Auckland Landowners throughout the country have voluntarily protected some Lynda Fleming Tel: 09 238 5739 Coromandel 81,300 hectares of their land through QEII covenants (or protection Hamish Kendal Tel: 07 866 0770 agreements). The Trust also helps by contributing funds for covenant North Waikato projects and advising landowners on managing their covenants. For Johlene Kelly Tel: 07 858 2271 more information see page 27. Waikato Hamish Dean Tel: 021 741 222 QEII also owns 27 properties which collectively protect over 1,800 Waitomo/Otorohanga hectares of significant habitat. These have mostly been gifted to the Malcolm Mackenzie Tel: 07 873 7728 Trust. Effective stewardship of these properties is greatly assisted by Bay of Plenty local communities and management committees. Stephen Hall Tel: 07 544 1227 Gisborne Malcolm Piper Tel/Fax: 06 867 0255 Hawke’s -

Fault Mechanism & Earthquakes Affecting Gisborne

http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Chapter One – Introduction CHAPTER ONE - Introduction 1.0 Introduction The Gisborne Region covers a land area of 8,265 km2 on the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand. This is approximately 4.9% of New Zealand's total land area. Neighboring regions are Hawkes Bay to the south and the Bay of Plenty to the north west (Figure 1). Provisional data from the 2006 census indicate that the population of the main city of Gisborne is ~44,400. The other major population centers are Ruatoria (~720), Tokomaru Bay (~450), Tolaga Bay (~860), and Te Karaka (~530) (Statistics New Zealand 2005). Figure 1 Image of the East Cape on the North Island, showing Gisborne, Tolaga Bay, Tokomaru Bay 1 Chapter One – Introduction The local authorities (Civil Defense) in Gisborne are aware of the risk and threat that tsunami pose to the region (Friday the 11th of May 2007 was the 130-year anniversary of a major tsunami that struck the area following an 8.3 magnitude earthquake off the coast of South America, also the recent earthquake in December 2007 was a reminder about Gisborne vulnerability.