George Peele's Senecanism and the Origins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship of the Dramatic Works of John Lyly to Later Elizabethan Comedies

Durham E-Theses The relationship of the dramatic works of John Lyly to later Elizabethan comedies Gilbert, Christopher G. How to cite: Gilbert, Christopher G. (1965) The relationship of the dramatic works of John Lyly to later Elizabethan comedies, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9816/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE RELATIONSHIP OP THE DRAMATIC WORKS OP JOHN LYLY TO LATER ELIZABETHAN COMEDIES A Thesis Submitted in candidature for the degree of Master of Arts of the University of Durham by Christopher G. Gilbert 1965 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. DECLARATION I declare this work is the result of my independent investigation. -

Representations of Spain in Early Modern English Drama

Saugata Bhaduri Polycolonial Angst: Representations of Spain in Early Modern English Drama One of the important questions that this conference1 requires us to explore is how Spain was represented in early modern English theatre, and to examine such representation especially against the backdrop of the emergence of these two nations as arguably the most important players in the unfolding game of global imperialism. This is precisely what this article proposes to do: to take up representative English plays of the period belonging to the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) which do mention Spain, analyse what the nature of their treat- ment of Spain is and hypothesise as to what may have been the reasons behind such a treatment.2 Given that England and Spain were at bitter war during these twenty years, and given furthermore that these two nations were the most prominent rivals in the global carving of the colonial pie that had already begun during this period, the commonsensical expectation from such plays, about the way Spain would be represented in them, should be of unambiguous Hispanophobia. There were several contextual reasons to occasion widespread Hispanophobia in the period. While Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1509) and its subsequent annulment (1533) had already sufficiently complicated Anglo-Hispanic relations, and their daughter Queen Mary I’s marriage to Philip II of Spain (1554) and his subsequent becoming the King of England and Ireland further aggravated the 1 The conference referred to here is the International Conference on Theatre Cultures within Globalizing Empires: Looking at Early Modern England and Spain, organised by the ERC Project “Early Modern European Drama and the Cultural Net (DramaNet),” at the Freie Universität, Ber- lin, November 15–16, 2012, where the preliminary version of this article was presented. -

Shakespeare As Literary Dramatist

SHAKESPEARE AS LITERARY DRAMATIST LUKAS ERNE published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lukas Erne 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdomat the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Adobe Garamond 11/12.5 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 82255 6 hardback Contents List of illustrations page ix Acknowledgments x Introduction 1 part i publication 1 The legitimation of printed playbooks in Shakespeare’s time 31 2 The making of “Shakespeare” 56 3 Shakespeare and the publication of his plays (I): the late sixteenth century 78 4 Shakespeare and the publication of his plays (II): the early seventeenth century 101 5 The players’ alleged opposition to print 115 part ii texts 6 Why size matters: “the two hours’ traffic of our stage” and the length of Shakespeare’s plays 131 7 Editorial policy and the length of Shakespeare’s plays 174 8 “Bad” quartos and their origins: Romeo and Juliet, Henry V , and Hamlet 192 9 Theatricality, literariness and the texts of Romeo and Juliet, Henry V , and Hamlet 220 vii viii Contents Appendix A: The plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries in print, 1584–1623 245 Appendix B: Heminge and Condell’s “Stolne, and surreptitious copies” and the Pavier quartos 255 Appendix C: Shakespeare and the circulation of dramatic manuscripts 259 Select bibliography 262 Index 278 Illustrations 1 Title page: The Passionate Pilgrim, 1612, STC 22343. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

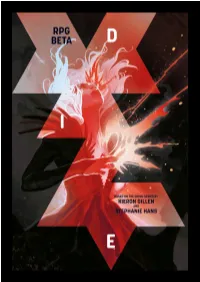

DIE RPG Beta Manual V1.Pdf

DIE: A ROLE-PLAYING GAME KIERON GILLEN ©2019 ART BY STEPHANIE HANS COVER DESIGN BY RIAN HUGHES Copyright © 2019 Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. All rights reserved. DIE, the Die logos, and the likenesses of all characters herein or hereon are trademarks of Kieron Gillen Ltd & Stéphanie Hans. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means (except for short excerpts for journalistic or review purposes) without the express written permission of Kieron Gillen Ltd or Stéphanie Hans. All names, characters, events, and places herein are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events, or places is coincidental. Representation: Law Offices of Harris M. Miller II, P.C. ([email protected]) CONTENTS 1) INTRODUCTION 2) THE WORLD OF DIE 3) PREPARATION 4) THE FIRST SESSION 5) PREPARING THE SECOND SESSION 6) THE SECOND SESSION 7) THE RULES 8) RUNNING THE ARCHETYPES 9) ADVICE FOR GAMESMASTERS 10) OTHER RESOURCES WELCOME I have a habit of being a little extra around my comics. I fear this is the most extra thing I’ve ever done. Alongside creating the comic DIE with Stephanie Hans, I developed the role-playing game you hold in your hands. Er… figure of speech. “PDF on your hard drive” doesn’t quite have the same ring. This RPG creates, in a miniaturized form, your own version of the first arc of DIE. As such, there’s some possible structural spoilers for the comic. I say “possible” because it really is your own version of the comic. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

The Appearance of Blacks on the Early Modern Stage: Love's

Early Theatre 17-2 (2014), 77–94 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.17.2.1206 matthieu a. chapman The Appearance of Blacks on the Early Modern Stage: Love’s Labour’s Lost’s African Connections to Court While scholarship is certain that white actors did appear in blackface on the Eliza- bethan stages, this paper argues for the additional possibility of actual moors and blacks appearing on stage in early modern London. Examining the positive social, political, and economic implications of using in performance these bodies per- ceived as exotic, I argue for the appearance of blacks in Love’s Labour’s Lost as a display of courtly power in its 1597–8 showing for Elizabeth I. Building on this precedent, Queen Anna’s staging of herself as black in the 1605 Masque of Black- ness, I argue, worked to assert the new Jacobean court’s power. In the year 1501, Spanish princess Catherine of Aragon arrived in England to marry Arthur, eldest son of Henry VII. The English greeted Catherine with much fanfare and were impressed with the pageantry of her entrance, which, as Sir Thomas More wrote, ‘thrilled the hearts of everyone’.1 In spite of the fanfare, not everything about Catherine’s entrance was entirely positive. The Spanish princess’s arrival brought not only a wife for the prince of Wales, but also attention to a confusion prevalent in English culture, the simultan- eous visibility and invisibility of blacks. Of the fifty-one members of Cath- erine of Aragon’s household to make the trip to England with her, two were black.2 Describing these individuals -

Group One: Theatrical Space, Time, and Place Adhaar Noor Desai

Group One: Theatrical Space, Time, and Place Adhaar Noor Desai “George Peele’s The Old Wives Tale and the Art of Interruption” My paper argues that George Peele’s The Old Wives Tale (1595) provides modern readers means for better apprehending the compositional logic – and compositional legibility – of early modern theatrical performance. Focusing on the play’s series of staged interruptions, which occur as speech acts, embodied movements, and, at significant moments, as both, I argue that Peele’s multimodal dramaturgy taps into a habits of composition and reception that drive the Elizabethan theater’s transformation from housing “playing,” the recreational activity, to presenting “plays” as crafted aesthetic artworks. To explain how the technical aspects of Elizabethan dramatic craft and their attendant protocols of representation shape the contours of audience response, I turn to writings on early modern Elizabethan architecture, which I find relies upon homologous principles of artificial craft. In my paper, I think through how Elizabethan architects saw their work as a self-conscious melding of humanistic theory and material practice, of “design” and implementation, with the aid of Jacques Derrida’s notion of the “architecture of the event,” which considers built environments as a form of writing via the shared centrality of “spacing.” Alongside this discussion, I consult recent scholarship by Simon Palfrey and Tiffany Stern, Henry S. Turner, and Evelyn Tribble on early modern practices of playing in order to present Peele’s play as a text unfolding over time, and its dialogue as palpably pre-written lines. I read The Old Wives Tale as a reflection on theatrical artifice itself by imagining it as building to be contemplated at once as a total composition and also as a navigable space that thrusts forward its crafted particulars, which it marks via intervening interruptions and self-consciously performative speech acts. -

George Geele

George Peele was born about 1558, and was educated at the grammar school of Christ's Hospital, of which his father James Peele, a maker of pageants, was clerk, and at Oxford, where he proceeded B.A. in 1577 and M.A. in 1579. When he returned to Oxford on business in 1583, two years after his departure for London, he was called upon to manage the performance of two Latin plays by William Gager for the entertainment of Alasco, a Polish prince, and in two sets of Latin elegiacs Gager commended Peele as wit and poet. The rest of his life was apparently spent in literary work in London among such friends as Greene, Lodge, Nashe, and Watson. Like other convivial spirits among the literary men of the time, Peele seems to have been given to excesses. These probably hastened his end, and were no doubt responsible for the ascription to him of a series of escapades and sayings, chiefly fabulous in all likelihood, which furnished material for the Jests of George Peele , published about 1605. He was buried in the Parish of St. James, Clerkenwell, November 9, 1596. Peele's extent work is predominantly dramatic. His first play, The Arraignment of Paris , was prepared for boys and acted before Elizabeth. It's poetic fancy, like the wit and conceit of Lyly 's prose dialogue, made its appeal to courtly taste. Nashe in the preface to Greene's Menaphon (1589) declares that it reveals the "pregnant dexterity of wit and manifold variety of invention" of Peele, whom he calls the great maker of phrases (" primum verborum artifex "). -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Othello and the "Plain Face" of Racism Author(S): Martin Orkin Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol

George Washington University Othello and the "plain face" Of Racism Author(s): Martin Orkin Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Summer, 1987), pp. 166-188 Published by: Folger Shakespeare Library in association with George Washington University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2870559 . Accessed: 16/07/2011 13:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=folger. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Folger Shakespeare Library and George Washington University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Shakespeare Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org Othello and the "plain face" Of Racism MARTIN ORKIN OLOMON T.