Near the Center of the Labyrinth: Krzysztof Penderecki in the New Millenium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jùáb «^Å„Šma

557149 bk Penderecki 30/09/2003 11:39 am Page 16 Quando corpus morietur, While my body here decays, DDD fac, ut animae donetur make my soul thy goodness praise, Paradisi gloria. safe in paradise with thee. PENDERECKI 8.557149 From the sequence ‘Stabat Mater’ for the Feast of the Seven Dolours of Our Lady St Luke Passion ∞ Evangelist, Christ and Chorus Evangelist, Christ and Chorus Kłosiƒska • Kruszewski • Tesarowicz • Kolberger • Malanowicz • Warsaw Boys Choir Erat autem fere hora sexta, et tenebrae factae sunt And it was about the sixth hour, and there was a in universam terram usque in horam nonam. darkness over all the earth until the ninth hour. Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra Et obscuratus est sol, et velum templi scissum est And the sun was darkened, and the veil of the temple was medium. Et clamans voce magna Iesus, ait: rent in the midst. And Jesus crying with a loud voice, said: Antoni Wit “Pater, in manus Tuas commendo spiritum meum.” “Father, into Thy hands I commend My spirit.” Consummatum est. “It is finished.” St Luke 23, 44-46 and St John 19, 30 ¶ Chorus and Soloists Chorus and Soloists In pulverem mortis dedixisti me. Thou hast brought me down into the dust of death… Crux fidelis… Faithful cross... Miserere, Deus meus… Have mercy, my God… In Te, Domine, speravi, In thee, O Lord, have I put my trust: non confundar in aeternum: let me never be put to confusion, in iustitia Tua libera me. deliver me in thy righteousness. Inclina ad me aurem Tuam, Bow down thine ear to me: accelera ut eruas me. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 665. - 2 - January 2021 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Adam, Claus: Vcl Con/ Barber: Die Natali - Kates vcl, cond.Mester 1975 S LOUISVILLE LS 745 A 12 2 Adams, John: Shaker Loops, Phrygian Gates - McCray pno, Ridge SQ, etc 1979 S 1750 ARCH S 1784 A 10 3 Baaren, Kees van: Musica per orchestra; Musica per organo/Brons, Carel: Prisms DONEMUS 72732 A 8 (organ) - Wolff organ, cond.Haitink , (score enclosed) S 4 Badings: Con for Orch/H.Andriessen: Kuhnau Var/Brahms: Sym 4 - Regionaal 2 x REGIONAAL JBTG A 15 Jeugd Orkest, cond.Sevenhuijsen live, 1982, 1984 S 7118401 5 Bax: Sym 3, The Happy Forest - London SO, cond.Downes (UK) (p.1969) S RCA SB 6806 A 8 6 Bernstein, Elmer: Summer and Smoke (sound track) - cond.comp S ENTRACTE ERS 6519 A 8 7 Bernstein, Elmer: The Magnificent Seven - cond.comp S LIBERTY EG 260581 A 8 8 Bernstein, Elmer: To Kill a Mockingbird (film music) - Royal PO, cond.E.Bernstein FILMMUSIC FMC 7 A 25 1976 S 9 Bernstein, Elmer: Walk on the Wild Side (soundtrack) - cond.comp S CHOREO AS 4 A 8 10 Bernstein, Ermler: Paris Swings (soundtrack) S CAPITOL ST 1288 A 8 11 Bolling: The Awakening (soundtrack) S ENTRACTE ERS 6520 A 8 12 Bretan, Nicolae: Ady Lieder - comp.pno & vocal (one song only), L.Konya bar, MHS 3779 A 8 F.Weiss, M.Berkofsky pno S 13 Castelnuovo-Tedesco: The Well-Tempered Guitars - Batendo Guitar Duo (gatefold) 2 x ETCETERA ETC 2009 A 15 (p.1986) S 14 Casterede, Jacques: Suite a danser - Hewitt Orch (light music) 10" DISCOPHILE SD 5 B+ 10 15 Dandara, Liviu: Timpul Suspendat, Affectus, Quadriforium III -

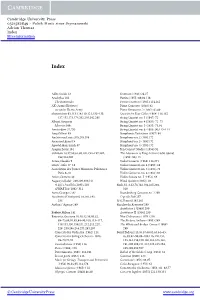

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Les Diables De Loudun De Krzysztof Penderecki 1969 : Histoire, Fiction, Ruptures Et Renouveau De L’Opéra

Les Diables de Loudun de Krzysztof Penderecki 1969 : histoire, fiction, ruptures et renouveau de l’opéra Martin Laliberté, Université Paris-Est, LISAA (EA 4120), UPEMLV, F-77454, Marne-la-Vallée, France A paraître dans Z. Przychodniak et G. Séginger (ed), Fiction et Histoire. Presses Universitaires de Strasbourg, coll. « Formes et Savoirs » Introduction Le compositeur contemporain Krzysztof Penderecki, compositeur emblématique de toute une génération en rupture avec la tradition musicale occidentale, a abordé le "grand genre" opératique en 1969 sous l'impulsion de Rolf Liebermann à l'Opéra de Hambourg. Les Diables de Loudun, d'après les fameux événements historiques de prétendues possessions diaboliques, de prêtre corrompu et autres orgies supposées, tels que revus par le « scandaleux » Aldous Huxley, a constitué un événement particulier pour l'opéra contemporain pour ses contre-pieds, ses ruptures stylistiques et techniques, dans un genre notoirement résistant aux innovations. L'oeuvre fit scandale par ses audaces scéniques et musicales et son instrumentation électrique. Le sous-texte politique offrait aussi une matière à débats importante. Le temps a passé depuis la création. Les idéologies musicales, artistiques et politiques ont muté et le mur de Berlin s’est effondré. Une version de cet opéra tournée pour la télévision est désormais disponible en DVD1 et rend possible un nouveau regard sur cette oeuvre2. Il est aujourd'hui possible de mettre en valeur ses différents aspects, en reliant notamment les questions d'histoire, de fiction et de ruptures. Cet article procède en trois parties. Un rappel de la biographie de Krzysztof Penderecki et du contexte musical global de cette époque, une présentation des faits historiques de Loudun et des nombreuses et intéressantes réécritures auxquelles ils ont donné lieu rendent possible une 1 Krzysztof Penderecki Die Teufel von Loudun (1969), dirigé pour la télé par Joachim Hess, DVD réédité par ArtHaus Musik, /Studio Hamburg, 2007. -

Penderecki Has Enjoyed an International Reputation for Music That Blends Direct, Emotional Appeal with Contemporary Compositional Techniques

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Since 1966, with the composition of the St Luke Passion (Naxos 8.557149), Penderecki has enjoyed an international reputation for music that blends direct, emotional appeal with contemporary compositional techniques. The neo-Romantic choral work, Te Deum, was inspired by the anointing of Karol Wojtyla as the first Polish Pope in 1978. Although Penderecki’s recent choral works have tended to be similarly monumental in scale, he has written several of a more compact DDD PENDERECKI: nature, such as Hymne an den heiligen Daniel, whose opening ranks as one of the composer’s most PENDERECKI: affecting. This disc closes with two works for strings: the experimental Polymorphia from 1961, 8.557980 and the expressive Chaconne, written in 2005 as a tribute to the late Pope John Paul II. Krzysztof Playing Time PENDERECKI 67:06 (b. 1933) Te Deum Te Deum Te Te Deum (1979-80)* 36:46 Deum Te 1 Part One 13:02 2 Part Two 7:53 3 Part Three 15:51 4 Hymne an den heiligen Daniel (1997)† 12:14 www.naxos.com Made in the EU Kommentar auf Deutsch Booklet notes in English ൿ 5 Polymorphia (1961) 10:48 & 6 Polish Requiem: Chaconne (2005) 7:18 Ꭿ 2007 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Izabela Kłosi´nska, Soprano* • Agnieszka Rehlis, Mezzo-soprano* Adam Zdunikowski, Tenor* • Piotr Nowacki, Bass* Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir*† (Henryk Wojnarowski, choirmaster) Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Sung texts are available at www.naxos.com/libretti/557980.htm 8.557980 Recorded from 5th to 7th September, 2005 (tracks 1-3), and on 29th September, 2005 (track 4), 8.557980 at Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Poland Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Lupa and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 1 and 4), and Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 2 and 3) • Publisher: Schott Musik Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse • Cover image: Grey Black Cross by Sybille Yates (dreamstime.com). -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Krzysztof Penderecki. Wandlungen Und Knotenpunkte Des Sch¨Opferischen Weges

Mieczys law Tomaszewski (Krak´ow) Krzysztof Penderecki. Wandlungen und Knotenpunkte des sch¨opferischen Weges Gleich am Anfang m¨ochte ich meine Hauptthese vorstellen. In sei- ner ganzen sch¨opferischen T¨atigkeit v e r ¨a n d e r t e s i c h Pendere- cki von Phase zu Phase und b l i e b doch d e r s e l b e. Auf der einen Seite Heinrich Schenker, auf der anderen Noam Chomsky haben uns darauf aufmerksam gemacht, dass jede mensch- liche Wirklichkeit aus mindestens z w e i S c h i c h t e n besteht: aus der O b e r f l ¨a c h e n s c h i c h t, die offen zu Tage tritt, und der t i e f e n { verborgenen, unsichtbaren {, jedoch generativen Schicht. Wenn wir uns diese Idee aneignen { hier naturlic¨ h nur als eine Me- tapher {, k¨onnen wir feststellen: Penderecki ver¨anderte sich an der Oberfl¨ache. In der Tiefenschicht blieb er unver¨andert. Oder: wenn er sich auch dort ver¨anderte, dann war es adagio\ und nicht allegro\. " " 1 Die T i e f e n s c h i c h t der Pers¨onlichkeit Krzysztof Pendereckis wurde in seinen jungen Jahren geformt, und sogar noch fruher:¨ zu einem bestimmten Zeitpunkt und an einem bestimmten Ort. Es war keine gute Zeit. Und es war auch kein besonders guter Ort.1 Zu oft marschierten hier Soldatentruppen von Westen nach Osten und von Osten nach Westen. Lediglich ein paar Kinderjahre in dem kleinen St¨adtchen irgendwo in Sudp¨ olen waren ruhig und idyllisch. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC -

![Penderecki’S Most Colorful and Extroverted [Pieces]’, the Credo Is a Sweeping, Lavishly Scored and Highly Romantic Setting of the Catholic Profession of Faith](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3813/penderecki-s-most-colorful-and-extroverted-pieces-the-credo-is-a-sweeping-lavishly-scored-and-highly-romantic-setting-of-the-catholic-profession-of-faith-973813.webp)

Penderecki’S Most Colorful and Extroverted [Pieces]’, the Credo Is a Sweeping, Lavishly Scored and Highly Romantic Setting of the Catholic Profession of Faith

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Described by USA Today as ‘one of Penderecki’s most colorful and extroverted [pieces]’, the Credo is a sweeping, lavishly scored and highly Romantic setting of the Catholic profession of faith. Its use of traditional tonality alongside passages of choral speech, ringing brass and exotic percussive effects marks it as a potent Neo-romantic masterpiece. Composed more than 30 years earlier, the short avant garde Cantata recalls the sound world of Ligeti and celebrates DDD PENDERECKI: the survival, over 600 years, of the Jagellonian University near Kraków. ‘Antoni Wit and his PENDERECKI: Polish forces are incomparable in this repertoire’ (Penderecki’s Utrenja, Naxos 8.572031 / David 8.572032 Hurwitz, ClassicsToday.com). Playing Time Krzysztof 56:27 PENDERECKI (b. 1933) 1 9 Credo - Credo (1998) 49:56 Credo 0 Cantata in honorem Almae Matris Universitatis Iagellonicae sescentos abhinc annos fundatae (1964) 6:31 Iwona Hossa, Soprano 1 • Aga Mikołaj, Soprano 2 www.naxos.com Disc made in Canada. Printed and assembled USA. Booklet notes in English ൿ & Ewa Wolak, Alto • Rafał Bartmin´ ski, Tenor Ꭿ Remigiusz Łukomski, Bass 2010 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Warsaw Boys’ Choir (Chorus-master: Krzysztof Kusiel-Moroz) Warsaw Philharmonic Choir (Chorus-master: Henryk Wojnarowski) Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit The sung texts and translations can be found inside the booklet, and can also be accessed at www.naxos.com/libretti/572032.htm • A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet Recorded at Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Warsaw, Poland, from 29th September to 1st October, 2008 8.572032 8.572032 (tracks 1-9), and on 9th September, 2008 (track 10) Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (CD Accord) Publisher: Schott Music International • Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse Cover image by Ken Toh (dreamstime.com). -

Erica Amelia Reiter

Krzysztof Penderecki's Cadenza for Viola Solo as a derivative of the Concerto for Viola and Orchestra: A numerical analysis and a performer's guide Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Reiter, Erica Amelia, 1968- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 13:40:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289622 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproductioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the origmal, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book.