The Land Question and Ethnicity in the Darjeeling Hills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KALIMPONG, PIN - 734301 E-Mail: [email protected] TEL : 03552-256353, 255009

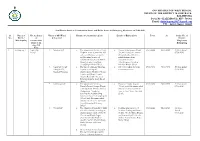

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT MAGISTRATE, KALIMPONG PO & PS - KALIMPONG, PIN - 734301 E-mail: [email protected] TEL : 03552-256353, 255009 At a Glance details of Containment Zones and Buffer Zones in Kalimpong District as on 19.06.2020 Sl. Name of No. & details Name of GP/Ward Details of Containment Zone Details of Buffer Zone From To Order No. of No. Block / of & Location District Municipality containment Magistrate Zone as on Kalimpong date, GP Wise 1. Kalimpong-I Eight (08) 1. Samthar G.P a. The Quarantine Centre of Lalit a. House of Gangaram Bhujel 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated Zones Pradhan at the community hall (North) House of Laxman 07.06.2020 of Lower Dong covering the Bhujel (South) 100 metre neighbouring houses of radial distance from Krishna Bhujel (North) Bimal containment zone Bhujel (South), Landslide (East)House of Krishna (East)Sukpal Bhujel (West) Bahadur Bhujel (West) 2. Yangmakum GP a. The House of Dong Tshering a. 100 metre radius from the 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated (Dinglali GP, Lepcha covering the containment zone 07.06.2020 Kambal Fyangtar) neighbouring Houses of Josing Lepcha and Birmit Lepcha (South) Road (North), Som Tshering Lepcha (East) Road (West) 3. Nimbong G.P a. The Quarantine centre of a. House of Timbu Lepcha 07.06.2020 20.06.2020 57/Con dated Kamala Rai and Anupa Bhujel (North) and 100 metres radial 07.06.2020 at Dalapchand Primary School, distance from containment Dalapchand, Nimbong, zone in East, West, North & covering the neighbouring South. -

The Land in Gorkhaland on the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India

The Land in Gorkhaland On the Edges of Belonging in Darjeeling, India SARAH BESKY Department of Anthropology and Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, USA Abstract Darjeeling, a district in the Himalayan foothills of the Indian state of West Bengal, is a former colonial “hill station.” It is world famous both as a destination for mountain tour- ists and as the source of some of the world’s most expensive and sought-after tea. For deca- des, Darjeeling’s majority population of Indian-Nepalis, or Gorkhas, have struggled for sub- national autonomy over the district and for the establishment of a separate Indian state of “Gorkhaland” there. In this article, I draw on ethnographic fieldwork conducted amid the Gorkhaland agitation in Darjeeling’s tea plantations and bustling tourist town. In many ways, Darjeeling is what Val Plumwood calls a “shadow place.” Shadow places are sites of extraction, invisible to centers of political and economic power yet essential to the global cir- culation of capital. The existence of shadow places troubles the notion that belonging can be “singularized” to a particular location or landscape. Building on this idea, I examine the encounters of Gorkha tea plantation workers, students, and city dwellers with landslides, a crumbling colonial infrastructure, and urban wildlife. While many analyses of subnational movements in India characterize them as struggles for land, I argue that in sites of colonial and capitalist extraction like hill stations, these struggles with land are equally important. In Darjeeling, senses of place and belonging are “edge effects”:theunstable,emergentresults of encounters between materials, species, and economies. -

Urban History of Darjeeling Through Phases : a Study of Society, Economy and Polity "The Queen of the Himalayas"

URBAN HISTORY OF DARJEELING THROUGH PHASES : A STUDY OF SOCIETY, ECONOMY AND POLITY OF "THE QUEEN OF THE HIMALAYAS" THESIS SUBMITTED BY SMT. NUPUR DAS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (ARTS) OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL 2007 RESEARCH SUPERVISOR Dr. Dilip Kumar Sarkar Controller of Examinations University of North Bengal CO-SUPERVISOR Professor Pradip Kumar Sengupta Department of Political Science University of North Bengal J<*eP 35^. \A 7)213 UL l.^i87(J7 0 \ OCT 2001 CONTENTS Page No. Preface (i)- (ii) PROLOGUE 01 - 25 Chapter- I : PRE-COLONIAL DARJEELING ... 26 - 48 Chapter- II : COLONIAL URBAN DARJEELING ... 49-106 Chapter-III : POST COLONIAL URBAN SOCIAL DARJEELING ... 107-138 Chapter - IV : POST-COLONIAL URBAN ECONOMIC DARJEELING ... 139-170 Chapter - V : POST-COLONIAL URBAN POLITICAL DARJEELING ... 171-199 Chapter - VI : EPILOGUE 200-218 BIBLIOGRAPHY ,. 219-250 APPENDICES : 251-301 (APPENDIX I to XII) PHOTOGRAPHS PREFACE My interest in the study of political history of Urban Darjeeling developed about two decades ago when I used to accompany my father during his official visits to the different corners of the hills of Darjeeling. Indeed, I have learnt from him my first lesson of history, society, economy, politics and administration of the hill town Darjeeling. My rearing in Darjeeling hills (from Kindergarten to College days) helped me to understand the issues with a difference. My parents provided the every possible congenial space to learn and understand the history of Darjeeling and history of the people of Darjeeling. Soon after my post- graduation from this University, located in the foot-hills of the Darjeeling Himalayas, I was encouraged to take up a study on Darjeeling by my teachers. -

Rethinking Gorkha Identity: Outside the Imperium of Discourse, Hegemony, and History

Peace and Democracy in South Asia, Volume 2, Numbers 1 & 2, 2006. RETHINKING GORKHA IDENTITY: OUTSIDE THE IMPERIUM OF DISCOURSE, HEGEMONY, AND HISTORY BIDHAN GOLAY ABSTRACT The primary focus of the paper is the study of the colonial construction of the Gorkha identity and its later day crisis. Taking the colonial encounter as the historic moment of its evolution, the paper makes an attempt to map the formation of the Gorkha identity over the last two hundred years or so by locating the process of formation within the colonial public sphere that emerged in Darjeeling in the early part of the twentieth century. The paper tries to cast new light on the nature of contestation and conflation between the colonial identity or the martial identity inscribed on the body of the Gorkha by the colonial discourse of “martial race” and the cultural identity that was emerging in course of time. It also tries to establish the fact that the colonial forms of representation of the “Gurkhas” as the “martial race” is still the dominant form of representation foreclosing all other forms of representation that had become possible as a new self-identity emerged with the cultural renaissance in Darjeeling and elsewhere. It also looks into the problem of double consciousness of the deterritorialised Gorkha subjectivity that is torn between two seemingly conflictual impulses of a primordially constructed notion of the Gorkha jati (community) and the demands of a modern nation-state. The paper also argues that the Gorkha identity has somewhat failed in securing a political space for its cultural identity leading to deep fissures in its multi layered identity. -

Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement by Dr

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: D History Archaeology & Anthropology Volume 14 Issue 1 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement By Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar ABN Seal College, India Introduction- The present Darjeeling District was formed in 1866 where Kalimpong was transformed to the Darjeeling District. It is to be noted that during Bhutanese regime Kalimpong was within the Western Duars. After the Anglo-Bhutanese war 1866 Kalimpong was transferred to Darjeeling District and the western Duars was transferred to Jalpaiguri District of the undivided Bengal. Hence the Darjeeling District was formed with the ceded territories of Sikkim and Bhutan. From the very beginning both Darjeeling and Western Duars were treated excluded area. The population of the Darjeeling was Composed of Lepchas, Nepalis, and Bhotias etc. Mech- Rajvamsis are found in the Terai plain. Presently, Nepalese are the majority group of population. With the introduction of the plantation economy and developed agricultural system, the British administration encouraged Nepalese to Settle in Darjeeling District. It appears from the census Report of 1901 that 61% population of Darjeeling belonged to Nepali community. GJHSS-D Classification : FOR Code : 120103 Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

St Joseph's Student Drowned in Kohima

WWW.EASTERNMIRRORNAGALAND.COM EASTERN MIRROR No one has the right to judge 0D=NEBłHAONAREASLAPEPEKJ IUłHIFKQNJAUġ'=?MQAHEJA 3APPAHPKOP=U=P#ANN=NE# ?D=HHAJCEJC-=J=I=C=PARAN@E?PW- Fernandez | P10 PEHHġPA=IW- WORLD ENTERTAINMENT SPORTS VOL. XVI NO. 234 | PAGES 12 ` 4/- RNI NO. NAGENG/2002/07906 DIMAPUR, SUNDAY, AUGUST 27, 2017 )ORRGKLW6HQDSDWLUHVLGHQWVÁHHWRKLJKHUJURXQG Our Correspondent of sugar and salt besides St Joseph’s student Imphal, August 26 other essential relief ma- (EMN): An orphanage terials as an immediate was washed away while measure to the orphanage more than 10 houses were affected by the flood. drowned in Kohima badly damaged due to “We’re also planning fresh flash flood and mud- to distribute relief materi- Our Correspondent of SJC and residents of Zhodi colony slide caused by heavy rain- als to the affected villagers Kohima, August 26 (EMN): A stu- along with the youth of Jakhama vil- fall in Manipur’s Senapati besides taking up other dent of St Joseph’s College, Jakhama lage and some volunteers of Southern district bordering Naga- necessary steps,” he said. was reportedly drowned on Saturday Angami Youth Organisation started the land in the wee hours of According to a vil- at the river that runs between Jakhama search for the drowned student. Saturday. However there lage elder, M Thowo, a and Viswema village. The incident took SAYO president Neisizo informed was no report of any hu- resident of Church road place at around 11 am when the girl, that the body of the girl was found in the man casualty. colony in Senapati, the along with eight other friends including afternoon, about hundred feet below the Many villagers have flood the people of Sena- four boys, was returning from Dzükou spot where she was swept away. -

List of Bridges in Sikkim Under Roads & Bridges Department

LIST OF BRIDGES IN SIKKIM UNDER ROADS & BRIDGES DEPARTMENT Sl. Total Length of District Division Road Name Bridge Type No. Bridge (m) 1 East Singtam Approach road to Goshkan Dara 120.00 Cable Suspension 2 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 65.00 Cable Suspension 3 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 92.50 Major 4 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 33.00 Medium Span RC 5 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 19.00 Medium Span RC 6 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 26.00 Medium Span RC 7 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 17.00 Medium Span RC 8 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 17.00 Medium Span RC 9 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 16.00 Medium Span RC 10 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 39.00 Medium Span RC 11 East Pakyong Ranipool-Lallurning-Pakyong 38.00 Medium Span STL 12 East Pakyong Assam Pakyong 32.00 Medium Span STL 13 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 24.00 Medium Span STL 14 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 32.00 Medium Span STL 15 East Pakyong Pakyong-Machung Rolep 31.50 Medium Span STL 16 East Pakyong Pakyong-Mamring-Tareythan 40.00 Medium Span STL 17 East Pakyong Rongli-Delepchand 9.00 Medium Span STL 18 East Singtam Duga-Pacheykhani 40.00 Medium Span STL 19 East Singtam Sangkhola-Sumin 42.00 Medium Span STL 20 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Bhusuk-Assam lingz 29.00 Medium Span STL 21 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 12.00 Medium Span STL 22 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 18.00 Medium Span STL 23 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 19.00 Medium Span STL 24 East Sub - Div -IV Penlong-tintek 25.00 Medium Span STL 25 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 12.00 Medium Span STL 26 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 19.00 Medium Span STL 27 East Sub - Div -IV Tintek-Dikchu 28.00 Medium Span STL 28 East Sub - Div -IV Gangtok-Rumtek Sang 25.00 Medium Span STL 29 East Sub - Div -IV Rumtek-Rey-Ranka 53.00 Medium Span STL Sl. -

Nepali’ Women of Darjeeling

INDIA’S NATIONALIST MOVEMENT AND THE PARTICIPATION OF ‘NEPALI’ WOMEN OF DARJEELING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE By KALYANI PAKHRIN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. RANJITA CHAKRABORTY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL DARJEELING, INDIA-734013 MARCH, 2017 Dedicated to my parents D E C L A R A T I O N I declare that the thesis entitled “India’s Nationalist Movement and the participation of ‘Nepali’ women of Darjeeling” has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. Ranjita Chakraborty, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of North Bengal. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. KALYANI PAKHRIN Department of Political Science University of North Bengal Darjeeling: 734013, West Bengal, India. Date:07/03/2017 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur Dr. Ranjita Chakraborty P.O. North Bengal University Department of Political Science ENLIGHTENMENT TO PERFECTION Dist. Darjeeling, 734013 West Bengal (India) Ref. No……………………………. Date: …………………….……… C E R T I F I C A T E I certify that Miss Kalyani Pakhrin has prepared the thesis entitled “India’s Nationalist Movement and the participation of ‘Nepali’ women of Darjeeling” for the award of Ph.D. degree of the University of North Bengal, under my guidance. I also certify that she has incorporated in her thesis the recommendations made by the Departmental Committee during her pre-submission seminar. She has carried out the work at the Department of Political Science, University of North Bengal. -

Cumulative Report of Number of Returnees Screened at Rangpo and Melli

5/8/2020 News Detail Navigation KNOW SIKKIM (/portalcontent/know-sikkim) MY GOVERNMENT (/portalcontent/my-government) SERVICES (http://www.sikkimservice.in/) DEPARTMENTS (/portalcontent/departments) (/home/index) Sign In (/account/login) News & Announcement CUMULATIVE REPORT OF NUMBER OF RETURNEES SCREENED AT RANGPO AND MELLI Date: 07-May-2020 Total Nation-Wide Registrations as on 07.05.2020 = 6084 Total Registrations from Siliguri, Darjeeling, Kalimpong & Surrounding Areas as on 07.05.2020 = 1601 Total Arrival/Screening at Rangpo Check post on 07.05.2020 = 79 (73 from East District and 6 from North District) Total Arrival / Screening at Melli Checkpost on 07.05.2020 = 93 (28 from South District & 65 from West District) Therefore, total returnees screened and quarantined from both check-posts today = 172. All the 172 returnees were quarantined in institutional quarantine Centres in the respective districts Terms of Use (/legal-link/terms-of-use) Disclaimer (/legal-link/disclaimer) Accessibility Statement (/legal-link/accessibility-statement) Link To Us (/legal-link/link-to-us) Copyright (/legal-link/copyright) FeedBack (/FeedBack) SiteMap (/SiteMap) OTHER LINKS Press Releases (/media/pressrelease) News & Announcement (/media/news-announcement) Awards & Achievements (/awards-achievement) Web Directory (/web-directory) Employment News (/media/employment-news) https://sikkim.gov.in/media/news-announcement/news-info?name=CUMULATIVE+REPORT+OF+NUMBER+OF+RETURNEES+SCREENED+AT… 1/2 5/8/2020 News Detail Notification & Circular (/media/notification-circular) Tender Notice (/tender) IT Vendors (https://sikkim.gov.in/departments/information-technology-department/list-of-it-empaneled- vendors) ABOUT US FAQ (/aboutus/faq) Site Map (/sitemap) Contact Us (/aboutus/contact-us) DOWNLOADS Useful Forms (/forms-report/useful-forms) Annual Reports (/forms-report/annual-reports) MEDIA Photo Gallery (/photogallery/albumlist) Video Gallery (/videogallery/albumlist) (https://www.nic.in/) (http://www.digitalindia.gov.in/) (http://goidirectory.nic.in/index.php) (https://eci.gov. -

Brochure Sikkim CS6.Indd

(2014-2021*) 1 THE RESURGENCE OF NORTHEAST THROUGH RAILWAYS An unprecedented increase in ϐinancial allocation for North Eastern India FUND ALLOCATION FOR RAIL CONNECTIVITY IN NORTH EASTERN STATES INCREASED BY 244% IN LAST SEVEN YEARS 7,000 6,000 5,000 244% 5,842 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 2,542 0 2009-14 2014-21 Average fund allocation per year in Rs. crore Projects Commissioned 402 km new line added 1119 km gauge conversion done 150 km double line added Survey of 1,178 km new line completed Rs. 41,599 crore Capital Expenditure in last 7 year Projects Under Progress 23 new lines project under construction (1,913 km) 12 double line project under construction (630 km) Anticipated expenditure Rs. 1,18,812 crore 9 new lines national projects 5,158 km new broad gauge line to be added All state Capitals of the Northeast to be connected with broad gauge lines 2 Highlights Large number of jobs created for gainful employment of locals 100% elimination of un-manned Level Crossing gates Mechanized cleaning of all station started from 2nd October, 2018 Divyang toilets provided in 257 stations Provided free high-speed WiFi at all nominated stations Provided 23 Lifts at 9 stations and 30 more to be provided at 21 stations Provided 18 Escalators at 8 stations and 12 more to be provided at 4 stations Key Beneϐits • All state capitals of the Northeast to be connected with broad gauge lines • Transforming Socio-economic landscape Sevoke Railway Station Tunneling works under progress 3 DEVELOPMENTAL WORKS IN SIKKIM ȍ2014ǧ2021Ȏ PROJECTS IN PROGRESS Sivok – Rangpo new line (44.96 km) at a cost of Rs. -

District Disaster Management Plan-2019,Kalimpong

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2019,KALIMPONG 1 FOREWORD It is a well-known fact that we all are living in a world where occurrence of disasters whether anthropological or natural are increasing year by year in terms of both magnitude and frequency. Many of the disasters can be attributed to man. We, human beings, strive to make our world comfortable and convenient for ourselves which we give a name ‘development’. However, in the process of development we take more from what Nature can offer and in turn we get more than what we had bargained for. Climate change, as the experts have said, is going to be one major harbinger of tumult to our world. Yet the reason for global warming which is the main cause of climate change is due to anthropological actions. Climate change will lead to major change in weather pattern around us and that mostly will not be good for all of us. And Kalimpong as a hilly district, as nestled in the lap of the hills as it may be, has its shares of disasters almost every year. Monsoon brings landslide and misery to many people. Landslides kill or maim people, kill cattle, destroy houses, destroy crops, sweep away road benches cutting of connectivity and in the interiors rivulets swell making it difficult for people particularly the students to come to school. Hailstorm sometimes destroys standing crops like cardamom resulting in huge loss of revenue. Almost every year lightning kills people. And in terms of earthquake the whole district falls in seismic zone IV. Therefore, Kalimpong district is a multi-hazard prone district and the District Disaster Management Plan is prepared accordingly. -

Issn –2395-1885 Issn

IJMDRR Research Paper E- ISSN –2395-1885 Impact Factor : 3.567 Peer Reviewed Journal ISSN -2395-1877 PLANTATION AND THE PEOPLE OF DARJEELING – DISPARITY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE REGION Sushma Rai Assistant Professor, Salesian College, Sonada, Darjeeling. Abstract The study of regional History has been expanding its horizon greatly in the recent years. In this respect exploration of man and environment relationship is a promising field for any social science researcher today. Over the last 160 years of the introduction of the plantation industry in Darjeeling region, many changes have taken place in the lifestyle of the migrant and the local labourers. The main purpose of the study is to explore their life and culture and also to learn how they adjusted themselves with the given environment with the changing scenario of the area. The study seeks to examine historically the socio-economic and political factors that reinforced the plantation labour in the Darjeeling hills. Key Words: Plantation, Darjeeling, Labourers. Introduction The history of the development of the plantation industry in the Darjeeling district dates back to the early fifties of the 19th century when the English entrepreneurs took lease of extensive land area on the mountain slopes of the Darjeeling Himalaya and started tea and cinchona plantation for commercial purpose. During the formative years of the introduction of the plantation industry the region was sparsely populated so labourers from various parts of India and her neighbouring countries were encouraged to settle in the fringe areas of the tea and cinchona gardens. As plantation was a labour intensive industry and the region was sparsely populated the Britishers started recruiting labourers from various parts of India like: Jharkhand, Bihar, Orissa, Santhal Parganas etc., and the neighbouring countries like Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim (as Sikkim was not a part of the Union of India at that time).