First & Last 1. Introduction in the Preceding Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrative Officials, Classified by Functions

i-*-.- I. •^1 TH E BO OK OF THE STATES SUPPLEl^ENT II JULY, 1961 ADMINISTRATIVE OfnciAts Classified by Functions m %r^ V. X:\ / • ! it m H^ g»- I' # f K- i 1 < 1 » I'-- THE BOOK ••<* OF THE STATES SUPPLEMENT IJ July, 1961 '.•**••** ' ******* ********* * * *.* ***** .*** ^^ *** / *** ^m *** '. - THE council OF STATE fiOVERNMEIITS ADMINKJTRATIV E O FFICIALS Classified by Fun ctions The Council of State Governments Chicago . ^ V /fJ I ^. sir:. \ i i- m m f. .V COPYRIGHT, 1961, BY - The Council of State Governments 131.3 East Sixtieth Street Chicago 37, Illinois m ¥ m-'^ m.. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 35-11433 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AUERICA «; Price, $2.50 \V FOREWORD This publication is the second of two Supplements to the 196Q-61 edition of The Book of the States, the biennial reference work on the organizationj working methods, financing and services of all the state governments. The present volimie, SupplementJI, based on information received from the states up to May 15, 1961, contains state-by-state rosters of principal administrative officials of the states, whether elected or appointed, and the Chief Justices of the Supreme Cou?&. It concludes with a roster of interstate agencies in many functional fields. Supplement I, issued in February, 1961, listed sill state officials and Supreme Court Justices elected by ^statewid'*., popular vote, and the members and officers of the legislatures. _j The Council of State Governments gratefully acknowledges the invaluable help of the members of the legislative service agencies and the many other state officials who have furnished the information used in this publication. -

Space Odyssey Alumni Fuel 60 Years of Space Exploration

SPRING/SUMMER 2018 THE MAGAZINE OF THE STEVENS ALUMNI ASSOCIAASSOCIATIONTION SPACE ODYSSEY ALUMNI FUEL 60 YEARS OF SPACE EXPLORATION IN THIS ISSUE: A LASTING LEGACY | LIFE AT BUZZFEED | CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF STEP DEPARTMENTS 2 PRESIDENT’S CORNER 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR/SOCIAL MEDIA 4-7 GRIST FROM THE MILL 7 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 42 SPORTS UPDATE 43-72 ALUMNI NEWS 44 SAA PRESIDENT’S LETTER 68 VITALS FEATURES 8-10 A TRIBUTE TO HIS ‘STUTE’ Richard F. Harries’ ’58 reunion-year gift makes Stevens history 11 STEVENS VENTURE CENTER ‘GRADUATES’ FIRST COMPANY FinTech Studios strikes out on its own 12-31 SPACE ODYSSEY Stevens alumni fuel 60 years (and counting) of space exploration 32-33 ENCHANTED EVENING See moments from the 2018 Stevens Awards Gala 34-35 PROFILE: CAROLINE AMABA ’12 36-38 STEP’S 50TH ANNIVERSARY The Stevens Technical Enrichment Program (STEP) will mark its 50th anniversary this fall, as its alumni reflect on its impact. 39 STEVENS RECEIVES ACE/FIDELITY INVESTMENTS AWARD ‘Turnaround’ not too strong a word to describe the university’s transformation 40 QUANTUM LEAP Physics team deploys, verifies pathbreaking three-node network 41 ROBOTIC DEVICE AIDS STROKE PATIENTS Mobility-assistance system will be tested by stroke patients at Kessler Institute Cover Photo: Shutterstock Images/NASA Cover Design: Simone Larson Design Campus Photo: Bob Handelman SPRING/SUMMER 2018 1 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR REMEMBERING PAUL MILLER SPRING/SUMMER 2018 VOL. 139, NO. 2 I had a chance to read the Winter 2018 edition of e Stevens Indicator and read Editor Beth Kissinger the story of former artist-in-residence Paul [email protected] Miller. -

Musique Et Camps De Concentration

Colloque « MusiqueColloque et « campsMusique de concentration »et camps de Conseilconcentration de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre » 2013 dans le cadre du programme « Transmission de la mémoire de l’Holocauste et prévention des crimes contre l’humanité » Conseil de l’Europe - 7 et 8 novembre 2013 Éditions du Forum Voix Etouffées en partenariat avec le Conseil de l’Europe 1 Musique et camps de concentration Éditeur : Amaury du Closel Co-éditeur : Conseil de l’Europe Contributeurs : Amaury du Closel Francesco Lotoro Dr. Milijana Pavlovic Dr. Katarzyna Naliwajek-Mazurek Ronald Leopoldi Dr. Suzanne Snizek Dr. Inna Klause Daniel Elphick Dr. David Fligg Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier Lloica Czackis Dr. Edward Hafer Jory Debenham Dr. Katia Chornik Les vues exprimées dans cet ouvrage sont de la responsabilité des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement la ligne officielle du Conseil de l’Europe. 2 Sommaire Amaury du Closel : Introduction 4 Francesco Lotoro : Searching for Lost Music 6 Dr Milijana Pavlovic : Alma Rosé and the Lagerkapelle Auschwitz 22 Dr Katarzyna Naliwajek–Mazurek : Music within the Nazi Genocide System in Occupied Poland: Facts and Testimonies 38 Ronald Leopoldi : Hermann Leopoldi et l’Hymne de Buchenwald 49 Dr Suzanne Snizek : Interned musicians 53 Dr Inna Klause : Musicocultural Behaviour of Gulag prisoners from the 1920s to 1950s 74 Daniel Elphick : Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Lines that have escaped destruction 97 Dr David Fligg : Positioning Gideon Klein 114 Dr. h.c. Philippe Olivier : La vie musicale dans le Ghetto de Vilne : un essai -

The Center for Food Studies: Connects School, Community, and Society in This Issue

Simon’s Rock MAGAZINE FALL 2014 InsIde thIs Issue: the Center for Food studies: Connects school, Community, and society IN THIS ISSUE 2 The Center for Food Studies Connects School, Community, and Society 4 New Programs Offer More Degrees, More Classes— and a Little Volcanic Ash 5 New Staff, New Faculty 6 Commencement 2014 7 Bard Academy at Simon’s Rock: The Education Innovation Continues 8 Faculty Spotlight: Dr. Chris Coggins 9 Letter from the Alumni Leadership Council Simon’s Rock Bookshelf 10 Donor Report 14 Alumni Spotlight: Eli Pariser ’96 15 Class Notes 17 Student Spotlight: Nate Shoobs ’12 Bard College at Simon’s Rock 84 Alford Road Great Barrington, MA 01230-1978 simons-rock.edu The magazine is a publication of the Office of Institutional Advancement and the Office of Communications. Design by Kelly Cade, Cade & Company Graphic Design. We welcome your feedback! Please send your suggestions, corrections, and responses to [email protected]. Cover: Community Garden. Photo: Dan Karp Pages 2, 3, 5, 7, 17. Photo: Dan Karp Pages 10, 13. Photo: Cathy Ingram FROM THE PROVOST Dear Simon’s Rock family and friends, It is startling to realize as I write this letter that the first semester of the academic year is nearly half over. Only a few weeks ago we were anticipating the arrival of the class of 2014. Now, just less than two months later, the new students we greeted on Opening Days have taken their place as full members of the Simon’s Rock community and are virtually indistinguishable from those who have been here for years. -

The Foreign Service Journal, November 2020

PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER 2020 GEORGE SHULTZ “ON TRUST” IN THEIR OWN WRITE BLACK WOMEN DIPLOMATS SPEAK OUT FOREIGN SERVICE November 2020 Volume 97, No. 9 Cover Story Focus on Foreign Service Authors 30 In Their Own Write We are pleased to present this year’s collection of books 26 by members of the Foreign Service community. On Trust A distinguished statesman shares 43 his thoughts on the path ahead, starting with the importance of Of Related Interest Here are recent books of interest to the foreign affairs community rebuilding trust. that were not written by members of the Foreign Service. By George P. Shultz FS Heritage Feature 66 72 America’s Slaughter South of the Overlooked Diplomats Sahara: No Scope for and Consuls Who Died “Business as Usual” in the Line of Duty Comprehensive strategies—and A discovery in a cemetery in Hong contingency plans if they fail—are Kong spurred a quest to find the names needed urgently to deal with the of U.S. diplomats whose ultimate complex and rapidly deteriorating sacrifice remained unacknowledged. situation in the Sahel. By Jason Vorderstrasse By Mark Wentling THE FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL | NOVEMBER 2020 5 FOREIGN SERVICE Perspectives Departments 7 101 10 Letters President’s Views Reflections A Message from George Shultz The Fastest Car in All Bolivia 12 Letters-Plus to the Foreign Service By George S. Herrmann By Eric Rubin 16 Talking Points 9 86 In Memory Letter from the Editor 93 Books Tending the Garden By Shawn Dorman 21 Speaking Out Marketplace Female, (Won’t) Curtail & Yale: Waiting to Exhale 96 Real Estate By Samantha Jackson, 102 98 Index to Advertisers Ayanda Francis-Gao, Local Lens Lisa-Felicia Akorli, Aja Kennedy, Nuuk, Greenland Annah Mwendar-Chaba 99 Classifieds By James P. -

Islamic Manner

Infidel by Ayaan Hirsi Ali Introduction One November morning in 2004, Theo van Gogh got up to go to work at his film production company in Amsterdam. He took out his old black bicycle and headed down a main road. Waiting in a doorway was a Moroccan man with a handgun and two butcher knives. As Theo cycled down the Linnaeusstraat, Muhammad Bouyeri approached. He pulled out his gun and shot Theo several times. Theo fell off his bike and lurched across the road, then collapsed. Bouyeri followed. Theo begged, "Can't we talk about this?" but Bouyeri shot him four more times. Then he took out one of his butcher knives and sawed into Theo's throat. With the other knife, he stabbed a five-page letter onto Theo's chest. The letter was addressed to me. Two months before, Theo and I had made a short film together. We called it Submission, Part 1. I intended one day to make Part 2. (Theo warned me that he would work on Part 2 only if I accepted some humor in it!) Part 1 was about defiance—about Muslim women who shift from total submission to God to a dialogue with their deity. They pray, but instead of casting down their eyes, these women look up, at Allah, with the words of the Quran tattooed on their skin. They tell Him honestly that if submission to Him brings them so much misery, and He remains silent, they may stop submitting. There is the woman who is flogged for committing adultery; another who is given in marriage to a man she loathes; another who is beaten by her husband on a regular basis; and another who is shunned by her father when he leams that his brother raped her. -

Dec 2019: Prof

Art by Dipak Kumbhar Art by Sohel Reja The Elixir Kitchen Maitre Chef Sai G Ramesh Les Chefs Debashis Tripathy, Dipak Kumbhar, Rekha P. T., Gopika Krishnan, Mrinal Arandhara, Kamla Devi Netam, Garima Tiwari, Subharaj Hossain, Saibalendu Sarkar, Md Kausar Raza. PASSING THE TORCH 1 Binny Cherayil demonstrates that he’s well–versed in verse. J N TATA PLANNED THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & SWAMI 2 VIVEKANANDA DID NOT INFLUENCE IT! E. Arunan busts a myth THRILLER: A HORRENDOUS AFFAIR 4 Saibalendu Sarkar is trying to become the next Dan Brown A TÊTÊ-À-TÊTÊ WITH DR. DEBASIS DAS 7 Make way for the new DD in town! Elixir reporters Rekha and Kausar have an adda with this new IPCian. BOOK REVIEWS 9 Gopika Krishnan and Sharon Gnanasekar give 5-star ratings to a couple of books. POEM: ANTIBIOTIC 11 Kritika Khulbe urges this li’l’ medicine to up its ante SARASWATI’S DAUGHTERS 12 The Elixir pays tribute to some excellent women scientists via a quiz put together by Kamla, Rekha, and Gopika. ORIGIN OF SANDAL SOAP 13 Every (south) Indian family has someone who swears by this soap. N. Munichandraiah tells us its history. 16 IN CONVERSATION WITH DR. SOUMYA SINGHA ROY Our new "lion king" tells Elixir correspondent Garima, "hakuna matata." 18 BLISSFUL RAHMANIA Sai Ramesh tells us that he's a Rahmanut. Poor fellow! 21 WELCOME FRESHERS!! 23 A PASSAGE TO INDIA Our South African visitor, Unathi Sidwaba tells us about her stay in Jungle Book land, otherwise called IISc, and how much she enjoys the com- pany of the Bandar-Log. -

First 1. Introduction in the Preceding Chapter, We

Chapter 10 FOCUS: First 1. Introduction In the preceding chapter, we examined two languages from the perspective of FOCUS and its alliance with the Patient function and the morphosyntax of sentence-initial position. The unifying link was a reliance on Behagel’s First Law. One of the conclusions to that discussion was that word order typologies which rely on syntactic (meaningless) tokens do not reveal the relations among languages that our descriptions suggest to be present. Witness the actual connections between the FOCUS initial languages Warao & Urarina, Bella Coola & Yogad, and Haida where their word orders (OVS/OSV, VSO, and no basic order, respectively) show no similarity. A semantic typology (Chapter 13) should be more illuminating. This chapter exists only because some languages have ended by invoking word order in the expression of FOCUS, and they are not random in that usage. Since not all languages turn to word order in signalling FOCUS, not all languages will find a place in this discussion. In that sense, this is not a true typology of FOCUS. But because FOCUS has impinged to shape the syntactic contour of clauses in at least some languages, the phenomenon touches upon the matter of word order typology more generally. Before proceeding to further discussion of FOCUS in relation to biases in its morphosyntactic expression, we will look a bit more at the notion of typing languages with syntactic word order. Recognizing failures in attempts to type languages using orders of the three tokens S, O, and V, Dryer (1997) proposes an alternative based on the couplets OV, VO, SV, and VS. -

Indiana Public Defender Membership Directory

Indiana Public Defender Membership Directory Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Adams County ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Allen County .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Bartholomew County .................................................................................................................................. 11 Benton County ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Blackford County ......................................................................................................................................... 14 Boone Count ............................................................................................................................................... 15 Brown County ............................................................................................................................................. 18 Carroll County ............................................................................................................................................. 19 Cass County ................................................................................................................................................ -

The First West Coast Punk Band!

BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 199: COUNTER CULTURE 1 [Film Poster or Lobby Card]: Marihuana: Weed with Roots in Hell! [No place: no publisher 1936] Original poster. Approximately 14" x 22½". Printed in black, red, and yellow. Modest age-toning in the white portions, else just about fine. Crudely designed poster or lobby card for the 1936 exploitation filmMarihuana advertising itself as a “Daring Drug Expose” and promising “Weird Orgies, Wild Parties, Unleashed Passions” and illustrated with a comely lass being shot up by a marihuana pusher. An iconic image, reproduced many times for everything from giclée prints to coffee mugs, this is an original and authentic 1936 poster. [BTC#390506] BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 199: COUNTER CULTURE Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. Dimensions of items, including artwork, are given 112 Nicholson Rd. width first. All items are returnable within 10 days if returned in the same condition as Gloucester City, NJ 08030 sent. Orders may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. phone: (856) 456-8008 Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger fax: (856) 456-1260 purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, Visa, [email protected] Mastercard, American Express, Discover, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. betweenthecovers.com Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis for orders of $200 or more via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. -

REGEN-COV in Patients Admitted to Hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Platform Trial SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX

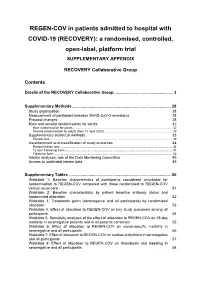

REGEN-COV in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX RECOVERY Collaborative Group Contents Details of the RECOVERY Collaborative Group .................................................... 3 Supplementary Methods ........................................................................................ 28 Study organization 28 Measurement of participant baseline SARS-CoV-2 serostatus 28 Protocol changes 28 Main and second randomisation for adults 32 Main randomisation for adults ...................................................................................................................... 32 Second randomisation for adults (from 14 April 2020) ................................................................................. 33 Supplementary statistical methods 33 Sample size ................................................................................................................................................. 33 Ascertainment and classification of study outcomes 34 Randomisation form .................................................................................................................................... 34 72 hour Follow-up Form............................................................................................................................... 37 Follow-up form ............................................................................................................................................. 42 Interim -

Active Licensed Pharmacists

2021 Active Licensed Pharmacists JANUARY No. Name Category facility 1. Aalaa Yaqoob Althawadi Pharmacist 2. Aayat Ebrahim Saeed Ali Pharmacy Technician Primary Health Care 3. Abbas Abdulnabi Husain Alasfoor Pharmacy Technician Inpatient Pharmacy -SMC 4. Abdalah Jalal Abdallah Medical Delegate WAEL PHARMACY CO. W.L.L 5. Abdalla A.Fattah Abdalla A.Fattah Pharmacist ALFATH PHARMACY.S.P.C 6. Abdelrahman Alaa A.Halim Medical Delegate YOUSUF MAHMOOD HUSSAIN COMPANY PHARMACY W.L.L 7. Abdu Rrahman Chootham Pharmacist NASSER PHARMACY 8. Abdul Azeez Aboobucker Pharmacist JAFFAR PHARMACY 9. Abdul Jalal Akbar Pharmacist FAMILY PHARMACY 10. ABDUL JAMEEL SHIHABUDEEN Pharmacist Al Hilal Hospital Company - BSC (Closed) 11. Abdul Javad Pasha Pharmacy Technician Maskati Pharmacy 12. Abdul Mannan Pharmacist DAR ALRAZI PHARMACY 13. Abdul Mubarak Jaffer Sathik Medical Delegate YOUSUF MAHMOOD HUSSAIN COMPANY PHARMACY W.L.L 14. Abdul Rahim Mohamed Pharmacist Salmaniya Medical Complex 15. Abdul Samadu Abdul Gafoor Khan Pharmacist BAHRAIN PHARMACY & GENERAL STORE 16. Abdul Wahab Khan Pharmacist MANAMA PHARMACY 17. Abdulasees Vatakke Illath Pharmacist Hamad Town Pharmacy 18. Abdulaziz A.husain Ahmed Pharmacist ALRAZI PHARMACY 19. Abdulaziz Khaled Ali Pharmacy Technician Ministry of Interior 20. Abdulhaleem Ghazi Metwaly Pharmacist ALDEERAH PHARMACY 2 W.L.L 21. Abduljalil Hasan Ahmed Pharmacy Technician Salmaniya Medical Complex 22. Abdullah Hamad Al-soliman Pharmacist Salmaniya Medical Complex 23. Abdulmuneim Ahmed Rafat Pharmacist Al Andalos Pharmacy 24. Abdulrahman Abdelmonem Abdulrahman Pharmacist Tabarak Pharmcy co W.L.L 25. Abdulrahman Ali Ahmed Alawadhi Pharmacist 26. Abdulrahman Nabeel Yusuf Pharmacist Salmaniya Medical Complex 27. Abdulsamad Naseeru Ddeen Pharmacy Technician MANAMA PHARMACY 28. Abdunnasir Irumbuzhi Pharmacist DAR AL-SHIFA MEDICAL CENTRE 29.