POSTERING in AUSTIN, TEXAS by Nels “Jagmo” Jacobson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Race Over the Years

P1 THE DAILY TEXAN LITTLE Serving the University of Texas at Austin community since 1900 DITTY Musician moves from ON THE WEB California to pursue a BAREFOOT MARCH passion for jingles Austinites and students walk shoeless to A video explores the meaning of ‘traditional the Capitol to benefit poor children values’ with regard to current legislation LIFE&ARTS PAGE 10 NEWS PAGE 5 @dailytexanonline.com >> Breaking news, blogs and more: dailytexanonline.com @thedailytexan facebook.com/dailytexan Wednesday, April 6, 2011 TEXAS RELAYS TODAY Calendar Monster’s Ball Lady Gaga will be performing at the Frank Erwin Center at 8 p.m. Tickets range from $51.50-$177. Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays Track and field teams will compete in the first day of the 84th Annual Clyde Littlefield Texas Relays at the Mike A. Myers Stadium. Texas Men’s Tennis Longhorns play Baylor at the Penick-Allison Tennis Center at 6 p.m. ‘Pauline and Felder | Daily Texan Staff file photo Paulette’ Texas’ Charlie Parker stretches for the tape to finish first in the 100-yard dash to remain undefeated on the season during the 1947 Texas Relays. Today marks the beginning of the The Belgian comedy-drama invitational’s 84th year in Austin. Collegiate and high school athletes will compete in the events, as well as several professional athletes. directed by Lieven Debrauwer will be shown in the Mezes Basement Bo.306 at 6:30 p.m. ‘Take Back the A race over the years Night’ By Julie Thompson Voices Against Violence will hold a rally to speak out against he Texas Relays started as a small, annually to the local economy. -

Central Texas Annual Festivals Festive Art, Music, Food and Cultural Events Where You Can Count on a Good Time Year After Year Celtic Cultural Center Presents: St

Central Texas Annual festivals Festive Art, Music, Food and Cultural Events where You Can Count on a good time Year After Year Celtic Cultural Center Presents: St. Patrick’s Day Austin Fiesta Gardens A fierce Irish tradition and fun for the whole family. Live traditional music, Irish dancing and presentations, games and other cultural activities. http://www.stpatricksdayaustin.com/ APRIL Urban Music Festival Auditorium Shores Urban Music Festival is a family-centric festival for R&B, jazz, funk and reggae music lovers, where national and local entertainment take center stage. http://urbanmusicfest.com/ Louisiana Swamp Thing & Crawfish Festival The Austin American Statesman parking lot It’s a Cajun festival in Texas! Loads of crawfish are consumed at this annual event, which features zydeco, brass band, funk, blues and rock music. http://www.roadwayevents.com/event/ Art City Austin Palmer Events Center FEBRUARY Nearly 200 national artists, top local restaurants, multiple music stages Carnaval Brasileiro and hands-on art activities make this one of the city’s favorite festivals. Palmer Events Center https://www.artallianceaustin.org/ Flamboyant costumes, Brazilian samba music and the uninhibited, spirited atmosphere make Austin’s Carnaval one of the biggest and Old Settler’s Music Festival best festivals of it’s kind outside of Brazil. http://sambaparty.com/ Salt Lick Pavilion and Camp Ben McCulloch Americana, roots rock, blues and bluegrass are performed at this Chinese New Year Celebration signature Central Texas music festival. Arts & crafts, camping, food and Chinatown Center local libations complete this down-home event. Chinese New Year starts on January 28, marking the Lunar New Year. -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

1 Is Austin Still Austin?

1 IS AUSTIN STILL AUSTIN? A CULTURAL ANALYSIS THROUGH SOUND John Stevens (TC 660H or TC 359T) Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 13, 2020 __________________________________________ Thomas Palaima Department of Classics Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Richard Brennes Athletics Second Reader 2 Abstract Author: John Stevens Title: Is Austin Still Austin? A Cultural Analysis Through Sound Supervisors: Thomas Palaima, Ph. D and Richard Brennes For the second half of the 20th century, Austin, Texas was defined by its culture and unique personality. The traits that defined the city ushered in a progressive community that was seldom found in the South. In the 1960s, much of the new and young demographic chose music as the medium to share ideas and find community. The following decades saw Austin become a mecca for live music. Austin’s changing culture became defined by the music heard in the plethora of music venues that graced the city streets. As the city recruited technology companies and developed its downtown, live music suffered. People from all over the world have moved to Austin, in part because of the unique culture and live music. The mass-migration these individuals took part in led to the downfall of the music industry in Austin. This thesis will explore the rise of music in Austin, its direct ties with culture, and the eventual loss of culture. I aim for the reader to finish this thesis and think about what direction we want the city to go in. 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisor Professor Thomas Palaima and second-reader Richard Brennes for the support and valuable contributions to my research. -

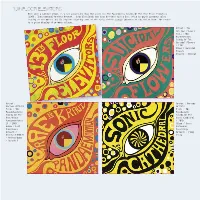

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

The Art of Reading: American Publishing Posters of the 1890S

6. Artist unknown 15. Joseph J. Gould Jr. 19. Joseph Christian Leyendecker 35. Edward Penfield 39. Edward Penfield CHECKLIST The Delineator October, 1897 (American, ca. 1876–after 1932) (American, 1875–1951) (American, 1866–1925) (American, 1866–1925) All dimensions listed are for the sheet size; Color lithograph Lippincott’s November, 1896 Inland Printer January, 1897 Harper’s July, 1897 Harper’s March, 1899 9 9 height precedes width. Titles reflect the text 11 /16 × 16 /16 inches Color lithograph Color lithograph Color lithograph Color lithograph 9 1 1 1 3 3 as it appears on each poster. The majority Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and 16 /16 × 13 /8 inches 22 /4 × 16 /4 inches 14 × 19 inches 15 /8 × 10 /4 inches of posters were printed using lithography, Donald Hastler Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and Museum Purchase: Funds Provided by Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and but many new printing processes debuted Donald Hastler Donald Hastler the Graphic Arts Council Donald Hastler 7. William H. Bradley during this decade. Because it is difficult or 2019.48.2 (American, 1868–1962) 16. Walter Conant Greenough 20. A. W. B. Lincoln 40. Edward Henry Potthast THE ART OF READING impossible to determine the precise method Harper’s Bazar Thanksgiving Number (American, active 1890s) (American, active 1890s) 36. Edward Penfield (American, 1857–1927) of production in the absence of contemporary 1895, 1895 A Knight of the Nets, 1896 Dead Man’s Court, 1895 (American, 1866–1925) The Century, July, 1896 documentation, -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

Jacaber-Kastor 2019.Pdf

Jacaeber Kastor: Psychedelic Sun By Carlo McCormick In turns perplexing, disorienting, wondrous and utterly beguiling, Jacaeber Kastor’s drawings make you look, look again and then still more, trying to find your way in their miasmic magic until at last, well, you discover the special pleasure of being truly lost. And when you think you’re done, when you’ve decoded the esoteric and abstract, conjured all the forms and meanings from these oceans of latency, answered the call of otherness as if it were the sphinx’s riddle- turn the work or flip your head, around and around, because there is no single perspective to read Kastor’s psychedelic topography: it is an entwined and constantly unfolding omniverse that has no right side up or upside down. If, in the course of your wanderings through Kastor’s meandering poetics of line and space, you come across the unexpected, the oddly familiar or the impossibly alien- for indeed you surely will, quite possible all at once with overwhelming simultaneity- and you ask yourself how did you even come to get here, you might also ask how indeed did this artist arrive at just such a place him- self. Make no mistake about it, Jacaeber Kastor is an intrepid voyager of body and mind, an adventurer without destination or designation, a man without return for even when he has somehow been there before he understands it as different, everything nuanced with the subtle shifts of impercep tible change, actuality always just beyond the tiny grasp of appearance, reason or replication. His art, like the convolutions of a restless mind guiding the inspired hand of uncertainty, is the tracings of a mind- traveler, a map to the nowhere that is everywhere, something so personally idiosyncratic that it marks a shared commons where likeness meets in a zone of compatible dissimilarity. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 Alan Schaefer The opening of the Vulcan Gas Company in 1967 marked a significant turning point in the history of music, art, and underground culture in Austin, Texas. Modeled after the psychedelic ballrooms of San Francisco, the Vulcan Gas Company presented the best of local and national psychedelic rock and roll as well as the kings and queens of the blues. The primary 46 medium for advertising performances at the 47 venue was the poster, though these posters were not simple examples of commercial art with stock publicity photos and redundant designs. The Vulcan Gas Company posters — a radical body of work drawing from psychedelia, surrealism, art nouveau, old west motifs, and portraiture — established a blueprint for the modern concert poster and helped articulate the visual language of Austin’s emerging underground scenes. The Vulcan Gas Company closed its doors in the spring of 1970, but a new decade witnessed the rapid development of Austin’s music scene and the posters that promoted it. Austin’s music poster artists offered a visual narrative of the music and culture of the city, and a substantial collection of these posters has found a home at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. The Wittliff Collections presented Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 in its gallery in the Alkek Library in 2015. The exhibition was curated by Katie Salzmann, lead archivist at the Wittliff Collections, and Alan Schaefer, a lecturer in the Department of English Jim Franklin. New Atlantis, Lavender Hill Express, Texas Pacific, Eternal Life Corp., and Georgetown Medical Band. -

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas BY Joshua Long 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Geography __________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson __________________________________ Dr. Jane Gibson __________________________________ Dr. Brent Metz __________________________________ Dr. J. Christopher Brown __________________________________ Dr. Shannon O’Lear Date Defended: June 5, 2008. The Dissertation Committee for Joshua Long certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas ___________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson Date Approved: June 10, 2008 ii Acknowledgments This page does not begin to represent the number of people who helped with this dissertation, but there are a few who must be recognized for their contributions. Red, this dissertation might have never materialized if you hadn’t answered a random email from a KU graduate student. Thank you for all your help and continuing advice. Eddie, you revealed pieces of Austin that I had only read about in books. Thank you. Betty, thank you for providing such a fair-minded perspective on city planning in Austin. It is easy to see why so many Austinites respect you. Richard, thank you for answering all my emails. Seriously, when do you sleep? Ricky, thanks for providing a great place to crash and for being a great guide. Mycha, thanks for all the insider info and for introducing me to RARE and Mean-Eyed Chris. -

TEEN AGE -A Construção Da Narrativa Gráfica a Partir Da Autobiografia

TEEN AGE A Construção da Narrativa Gráfica a Partir da Autobiografia Ana Raquel Cunha Diogo Relatório de Projeto para Obtenção de grau de Mestre em Artes Plásticas, Especialização em Desenho Orientador Professor Doutor Mário Moura Porto, 2019 Agradecimentos | i Quero agradecer ao meu orientador, Professor Mário Moura, pela sua disponibilidade em orientar-me, e acompanhar-me ao longo deste processo de trabalho. Agradeço principalmente aos meus pais pelo apoio e esforço que sempre fizeram ao longo destes anos de estudo. A Bárbara e Maria, que sempre me acompanharam durante este caminho e sempre me incentivaram para continuar, às suas recomendações e conhecimentos partilhados. Ao Pedro, pela paciência e motivação, e por me ajudar a nunca desistir. Aos meus colegas e amigos de mestrado, pelos bons e maus momentos, entreajuda, partilha de ideias e opiniões. Resumo | ii O presente relatório de projeto tem como principal objetivo abordar a banda desenhada autobiográfica como um modo expressivo de contar histórias aos quadradinhos em que os autores se assumem nas suas histórias como personagens, da mesma forma que se expressam perante a sociedade. O nosso caso de estudo é a banda desenhada do movimento artístico norte-americano criado na década de 60 e chamado Comix-Underground. A autobiografia é uma forma inevitável de exprimir o pessoal de cada um, visível ao leitor. Falamos assim de um projeto autorrepresentativo e do papel da mulher na sociedade nomeadamente na prática de skate na qual é assumida com a dominação masculina e se torna visível a desigualdade entre estes experienciando assim pequenos episódios de discriminação, preconceitos e estereótipos presentes na modalidade.