The Radiochemistry of Polonium COMMITTEE on NUCLEAR SCIENCE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/074683 Al 19 May 2016 (19.05.2016) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C12N 15/10 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/DK20 15/050343 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 11 November 2015 ( 11. 1 1.2015) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (25) Filing Language: English PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, (26) Publication Language: English SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: PA 2014 00655 11 November 2014 ( 11. 1 1.2014) DK (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/077,933 11 November 2014 ( 11. 11.2014) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 62/202,3 18 7 August 2015 (07.08.2015) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, (71) Applicant: LUNDORF PEDERSEN MATERIALS APS TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, [DK/DK]; Nordvej 16 B, Himmelev, DK-4000 Roskilde DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, (DK). -

List of Lists

United States Office of Solid Waste EPA 550-B-10-001 Environmental Protection and Emergency Response May 2010 Agency www.epa.gov/emergencies LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right- To-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act • EPCRA Section 302 Extremely Hazardous Substances • CERCLA Hazardous Substances • EPCRA Section 313 Toxic Chemicals • CAA 112(r) Regulated Chemicals For Accidental Release Prevention Office of Emergency Management This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction................................................................................................................................................ i List of Lists – Conslidated List of Chemicals (by CAS #) Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act ................................................. 1 Appendix A: Alphabetical Listing of Consolidated List ..................................................................... A-1 Appendix B: Radionuclides Listed Under CERCLA .......................................................................... B-1 Appendix C: RCRA Waste Streams and Unlisted Hazardous Wastes................................................ C-1 This page intentionally left blank. LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals -

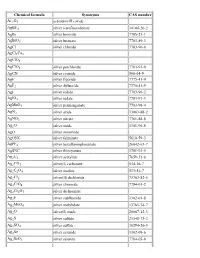

List of Chemical Formulas

Chemical formula Synonyms CAS number Ac2O3 actinium(III) oxide AgBF4 silver tetrafluoroborate 14104-20-2 AgBr silver bromide 7785-23-1 AgBrO3 silver bromate 7783-89-3 AgCl silver chloride 7783-90-6 AgCl3Cu2 AgClO3 AgClO4 silver perchlorate 7783-93-9 AgCN silver cyanide 506-64-9 AgF silver fluoride 7775-41-9 AgF2 silver difluoride 7775-41-9 AgI silver iodide 7783-96-2 AgIO3 silver iodate 7783-97-3 AgMnO4 silver permanganate 7783-98-4 AgN3 silver azide 13863-88-2 AgNO3 silver nitrate 7761-88-8 Ag2O silver oxide 1301-96-8 AgO silver monoxide AgONC silver fulminate 5610-59-3 AgPF6 silver hexafluorophosphate 26042-63-7 AgSNC silver thiocyanate 1701-93-5 Ag2C2 silver acetylide 7659-31-6 Ag2CO3 silver(I) carbonate 534-16-7 Ag2C2O4 silver oxalate 533-51-7 Ag2Cl2 silver(II) dichloride 75763-82-5 Ag2CrO4 silver chromate 7784-01-2 Ag2Cr2O7 silver dichromate Ag2F silver subfluoride 1302-01-8 Ag2MoO4 silver molybdate 13765-74-7 Ag2O silver(I) oxide 20667-12-3 Ag2S silver sulfide 21548-73-2 Ag2SO4 silver sulfate 10294-26-5 Ag2Se silver selenide 1302-09-6 Ag2SeO3 silver selenite 7784-05-6 Ag2SeO4 silver selenate 7784-07-8 Ag2Te silver(I) telluride 12002-99-2 Ag3Br2 silver dibromide 11078-32-3 Ag3Br3 silver tribromide 11078-33-4 Ag3Cl3 silver(III) trichloride 12444-96-1 Ag3I3 silver(III) triiodide 37375-12-5 Ag3PO4 silver phosphate 7784-09-0 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041-48-4 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279-70-7 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359-97-3 AlBr3 aluminium tribromide 7727-15-3 AlCl aluminium monochloride 13595-81-8 AlClF aluminium chloride fluoride -

Environmental Protection Agency § 302.4

Environmental Protection Agency § 302.4 State, municipality, commission, polit- ern Marianas, and any other territory ical subdivision of a State, or any or possession over which the United interstate body; States has jurisdiction; and Release means any spilling, leaking, Vessel means every description of pumping, pouring, emitting, emptying, watercraft or other artificial contriv- discharging, injecting, escaping, leach- ance used, or capable of being used, as ing, dumping, or disposing into the en- a means of transportation on water. vironment (including the abandonment or discarding of barrels, containers, [50 FR 13474, Apr. 4, 1985, as amended at 67 FR 45321, July 9, 2002] and other closed receptacles containing any hazardous substance or pollutant § 302.4 Designation of hazardous sub- or contaminant), but excludes: stances. (1) Any release which results in expo- (a) Listed hazardous substances. The sure to persons solely within a work- place, with respect to a claim which elements and compounds and haz- such persons may assert against the ardous wastes appearing in table 302.4 employer of such persons; are designated as hazardous substances (2) Emissions from the engine ex- under section 102(a) of the Act. haust of a motor vehicle, rolling stock, (b) Unlisted hazardous substances. A aircraft, vessel, or pipeline pumping solid waste, as defined in 40 CFR 261.2, station engine; which is not excluded from regulation (3) Release of source, byproduct, or as a hazardous waste under 40 CFR special nuclear material from a nuclear 261.4(b), is a hazardous substance under incident, as those terms are defined in section 101(14) of the Act if it exhibits the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, if such any of the characteristics identified in release is subject to requirements with 40 CFR 261.20 through 261.24. -

Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 2005)

NOMENCLATURE OF INORGANIC CHEMISTRY IUPAC Recommendations 2005 IUPAC Periodic Table of the Elements 118 1 2 21314151617 H He 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be B C N O F Ne 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 3456 78910 11 12 Na Mg Al Si P S Cl Ar 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe 55 56 * 57− 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 Cs Ba lanthanoids Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au Hg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn 87 88 ‡ 89− 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 Fr Ra actinoids Rf Db Sg Bh Hs Mt Ds Rg Uub Uut Uuq Uup Uuh Uus Uuo * 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 La Ce Pr Nd Pm Sm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb Lu ‡ 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Ac Th Pa U Np Pu Am Cm Bk Cf Es Fm Md No Lr International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC RECOMMENDATIONS 2005 Issued by the Division of Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation in collaboration with the Division of Inorganic Chemistry Prepared for publication by Neil G. -

Potential Military Chemical/Biological Agents and Compounds (FM 3-11.9)

ARMY, MARINE CORPS, NAVY, AIR FORCE POTENTIAL MILITARY CHEMICAL/BIOLOGICAL AGENTS AND COMPOUNDS FM 3-11.9 MCRP 3-37.1B NTRP 3-11.32 AFTTP(I) 3-2.55 JANUARY 2005 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. MULTISERVICE TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, AND PROCEDURES FOREWORD This publication has been prepared under our direction for use by our respective commands and other commands as appropriate. STANLEY H. LILLIE EDWARD HANLON, JR. Brigadier General, USA Lieutenant General, USMC Commandant Deputy Commandant US Army Chemical School for Combat Development JOHN M. KELLY BENTLEY B. RAYBURN Rear Admiral, USN Major General, USAF Commander Commander Navy Warfare Development Command Headquarters Air Force Doctrine Center This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online <www.us.army.mil>. PREFACE 1. Scope This document provides commanders and staffs with general information and technical data concerning chemical/biological (CB) agents and other compounds of military interest such as toxic industrial chemicals (TIC). It explains the use; classification; and physical, chemical, and physiological properties of these agents and compounds. Users of this manual are nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC)/chemical, biological, and radiological (CBR) staff officers, NBC noncommissioned officers (NCOs), staff weather officers (SWOs), NBC medical defense officers, medical readiness officers, medical intelligence officers, field medical treatment officers, and others involved in planning battlefield operations in an NBC environment. 2. Purpose This publication provides a technical reference for CB agents and related compounds. The technical information furnished provides data that can be used to support operational assessments based on intelligence preparation of the battlespace (IPB). 3. Application The audience for this publication is NBC/CBR staff personnel and commanders tasked with planning, preparing for, and conducting military operations. -

Environmental Protection Agency § 302.4

Environmental Protection Agency § 302.4 (4) Applicability date. This definition (4) The normal application of fer- is applicable beginning on February 6, tilizer; 2020. Reportable quantity (‘‘RQ’’) means Offshore facility means any facility of that quantity, as set forth in this part, any kind located in, on, or under, any the release of which requires notifica- of the navigable waters of the United tion pursuant to this part; States, and any facility of any kind United States include the several which is subject to the jurisdiction of States of the United States, the Dis- the United States and is located in, on, trict of Columbia, the Commonwealth or under any other waters, other than of Puerto Rico, Guam, American a vessel or a public vessel; Samoa, the United States Virgin Is- Onshore facility means any facility lands, the Commonwealth of the North- (including, but not limited to, motor ern Marianas, and any other territory vehicles and rolling stock) of any kind or possession over which the United located in, on, or under, any land or States has jurisdiction; and non-navigable waters within the Vessel means every description of United States; watercraft or other artificial contriv- Person means an individual, firm, ance used, or capable of being used, as corporation, association, partnership, a means of transportation on water. consortium, joint venture, commercial [50 FR 13474, Apr. 4, 1985, as amended at 67 entity, United States Government, FR 45321, July 9, 2002; 73 FR 76959, Dec. 18, State, municipality, commission, polit- 2008; 80 FR 37123, June 29, 2015; 83 FR 5209, ical subdivision of a State, or any Feb. -

Guide for the Selection of Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Decontamination Equipment for Emergency First Responders

Guide for the Selection of Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Decontamination Equipment for Emergency First Responders Preparedness Directorate Office of Grants and Training Guide 103–06 March 2007 2nd Edition Homeland Security DRAFT Guide for the Selection of Biological, Chemical, Radiological, and Nuclear Decontamination Equipment for Emergency First Responders Guide 103–06 Supersedes NIJ Guide 103–00, Guide for the Selection of Chemical and Biological Decontamination Equipment for Emergency First Responders, Volume I and Volume II, dated October 2001 Dr. Alim A. Fatah1 Richard D. Arcilesi, Jr.2 Adam K. Judd2 Laurel E. O’Connor2 Charlotte H. Lattin2 Corrie Y. Wells2 Coordination by: Office of Law Enforcement Standards National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899–8102 Prepared for: U.S. Department of Homeland Security Preparedness Directorate Office of Grants and Training Systems Support Division 810 7th Street, NW Washington, DC 20531 March 2007 1 National Institute of Standards and Technology, Office of Law Enforcement Standards. 2 Battelle. This guide was prepared for the Preparedness Directorate’s Office of Grants and Training (G&T) Systems Support Division (SSD) by the Office of Law Enforcement Standards at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) under Interagency Agreement 94–IJ–R–004, Project No. 99–060–CBW. It was also prepared under CBIAC contract No. SP0700–00–D–3180 and Interagency Agreement M92361 between NIST and the Department of Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). The authors wish to thank Ms. Kathleen Higgins of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) for programmatic support and for numerous valuable discussions concerning the contents of this document. -

Consolidated List of Chemicals Subject to EPCRA + Section 112(R)

United States Office of Land EPA 550-B-20-001 Environmental Protection and August 2020 Agency Emergency Management www.epa.gov/epcra LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right- To-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act • EPCRA Section 302 Extremely Hazardous Substances • CERCLA Hazardous Substances • EPCRA Section 313 Toxic Chemicals • CAA 112(r) Regulated Chemicals for Accidental Release Prevention TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 List of Lists: Consolidated List of Chemicals (By CAS Number) ................................................. 1 Appendix A: Consolidated List of Chemicals (By Alphabetical Name) .................................... A-1 Appendix B: Radionuclides Listed Under CERCLA ................................................................. B-1 Appendix C: RCRA Waste Streams and Unlisted Hazardous Wastes ....................................... C-1 Appendix D: EPCRA Section 313, Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Chemical Categories ........ D-1 Appendix E: ................................................................................................................................. E-1 EPCRA Section 313 (TRI) PER- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances CAS Number Listing ................... E-1 EPCRA Section 313 (TRI) PER- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances -

CHAPTER 28 INORGANIC CHEMICALS; ORGANIC OR INORGANIC COMPOUNDS of PRECIOUS METALS, of RARE-EARTH METALS, of RADIOACTIVE ELEMENTS OR of ISOTOPES VI 28-1 Notes 1

)&f1y3X SECTION VI PRODUCTS OF THE CHEMICAL OR ALLIED INDUSTRIES VI-1 Notes 1. (a) Goods (other than radioactive ores) answering to a description in heading 2844 or 2845 are to be classified in those headings and in no other heading of the tariff schedule. (b) Subject to paragraph (a) above, goods answering to a description in heading 2843 or 2846 are to be classified in those headings and in no other heading of this section. 2. Subject to note 1 above, goods classifiable in heading 3004, 3005, 3006, 3212, 3303, 3304, 3305, 3306, 3307, 3506, 3707 or 3808 by reason of being put up in measured doses or for retail sale are to be classified in those headings and in no other heading of the tariff schedule. 3. Goods put up in sets consisting of two or more separate constituents, some or all of which fall in this section and are intended to be mixed together to obtain a product of section VI or VII, are to be classified in the heading appropriate to that product, provided that the constituents are: (a) Having regard to the manner in which they are put up, clearly identifiable as being intended to be used together without first being repacked; (b) Entered together; and (c) Identifiable, whether by their nature or by the relative proportions in which they are present, as being complementary one to another. Additional U.S. Notes 1. In determining the amount of duty applicable to a solution of a single compound in water subject to duty in this section at a specific rate, an allowance in weight or volume, as the case may be, shall be made for the water in excess of any water of crystallization which may be present in the undissolved compound.