Reining in the Crown's Authority on Dissolution: the Fixed-Term

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Together Against Pallister's Cuts

FALL 2019 MANITOBA FEDERATION OF LABOUR President Rebeck speaks at Labour Day rally at the Manitoba Legislature United together against Pallister’s cuts Sisters, brothers and friends, the labour movement had a busy summer, and after the snap provincial election we face another term of the Pallister 2019 MFL Health and government and its anti-union agenda. Safety Report Card ( P. 3) However, working families can also count on a stronger NDP opposition in the Manitoba Legislature to stand up for their interests, as the NDP gained six seats. Four more years of As we have done for the previous 3.5 years, Manitoba’s unions will continue Brian Pallister ( P. 4) to be a strong voice on behalf of working families against the Pallister government’s cuts and privatization moves. KEVIN REBECK As Labour Day fell during the provincial election campaign, unions and labour activists joined together for a march from the Winnipeg General Strike streetcar monument to the Manitoba Fight for a Fair Canada this election ( P. 6) Legislature, as well as community events in other communities throughout the province. On the steps of the Legislature, I was proud to join with other speakers like NDP leader Wab Kinew, and NDP candidate for Winnipeg Centre Leah Gazan to stress the need for a united labour movement to stand up and fight back against Conservative governments and their plans to hurt working families. On the municipal front, the Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1505 continues to stand up for its members in contract negotiations with the City of Winnipeg. AT.USW9074/DD.cope342 Cont’d on Page 2 Manitoba Federation of Labour // 303-275 Broadway, Winnipeg, MB R3C 4M6 // MFL.ca United together, cont’d 1 ATU 1505 members have been without a contract since January, and the union continues to focus on key issues for its members in negotiations, including better bus schedules, recovery time for transit drivers and mental health supports. -

Strengthening Canadian Engagement in Eastern Europe and Central Asia

STRENGTHENING CANADIAN ENGAGEMENT IN EASTERN EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA UZBEKISTAN 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Hon. Robert D. Nault Chair NOVEMBER 2017 Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. -

Understanding Stephen Harper

HARPER Edited by Teresa Healy www.policyalternatives.ca Photo: Hanson/THE Tom CANADIAN PRESS Understanding Stephen Harper The long view Steve Patten CANAdIANs Need to understand the political and ideological tem- perament of politicians like Stephen Harper — men and women who aspire to political leadership. While we can gain important insights by reviewing the Harper gov- ernment’s policies and record since the 2006 election, it is also essential that we step back and take a longer view, considering Stephen Harper’s two decades of political involvement prior to winning the country’s highest political office. What does Harper’s long record of engagement in conservative politics tell us about his political character? This chapter is organized around a series of questions about Stephen Harper’s political and ideological character. Is he really, as his support- ers claim, “the smartest guy in the room”? To what extent is he a con- servative ideologue versus being a political pragmatist? What type of conservatism does he embrace? What does the company he keeps tell us about his political character? I will argue that Stephen Harper is an economic conservative whose early political motivations were deeply ideological. While his keen sense of strategic pragmatism has allowed him to make peace with both conservative populism and the tradition- alism of social conservatism, he continues to marginalize red toryism within the Canadian conservative family. He surrounds himself with Governance 25 like-minded conservatives and retains a long-held desire to transform Canada in his conservative image. The smartest guy in the room, or the most strategic? When Stephen Harper first came to the attention of political observers, it was as one of the leading “thinkers” behind the fledgling Reform Party of Canada. -

Municipal Amalgamations)

Bill 33 –The Municipal Modernization Act (Municipal Amalgamations) JESSICA DAVENPORT & G E R R I T THEULE I. INTRODUCTION anitoba’s 197 municipalities were the subject of contention and legislative focus during the Second Session of the M Fortieth Legislature. The New Democratic Party (NDP) government introduced Bill 33-The Municipal Modernization Act (Municipal Amalgamations)1 which began the restructuring of small municipalities. The objective behind Bill 33 was to modernize governance through amalgamations of municipalities with populations below 1,000. The Municipal Modernization Act altered the existing process for amalgamations contained within The Municipal Act2 by requiring all affected municipalities to present amalgamation plans and by-passing the usual investigative and reporting stages. The Bill encountered significant opposition in both the Legislative Assembly and the public discourse. Notably, few voices opposed municipal restructuring. Rather, the criticism was levelled at the lack of consultative processes in the time leading up to the introduction of the Bill and in the implementation of the amalgamations. Neither the B.A. (Hons), J.D. (2015). The authors would like to thank Dr. Bryan Schwartz and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this work. J.D. (2015). 1 Bill 33, The Municipal Modernization Act (Municipal Amalgamations), 2nd Sess, 40th Leg, Manitoba, 2013 (assented to 13 September 2013) [The Bill or Bill 33]. 2 The Municipal Act, CCSM, c M225. 154 MANITOBA LAW JOURNAL | VOLUME 37 NUMBER 2 Progressive Conservatives nor the Association of Manitoba Municipalities (AMM) opposed amalgamations in theory. Increasing the length of time before amalgamation plans were due or adding in mechanisms for greater consideration of public opinion would have removed the wind from the sails of opponents to Bill 33. -

February 28Th, 2021 the Honourable Brian Pallister Premier of Manitoba

February 28th, 2021 The Honourable Brian Pallister Premier of Manitoba Room 204 Legislative Building 450 Broadway, Winnipeg, MB R3C 0V8 Dear Premier Pallister, In January, 2021, I wrote to you encouraging the Province of Manitoba to ensure the full participation of the Manitoba Metis Federation in Manitoba’s vaccine planning and distribution. I was hopeful, after conversations with Ministers Stefanson and Clarke, that progress was being made. While I understand that some meetings have taken place, it is unfortunate that significant issues appear to remain with regards to the vaccine distribution process in Manitoba – notably the issue of equal access for all Indigenous populations. I read with great concern the CBC Manitoba article of February 24th, 2021 that outlined that Métis and Inuit citizens will not be prioritized to receive COVID-19 vaccines. The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) states that “adults living in Indigenous communities, which include First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, where infection can have disproportionate consequences such as those living in remote or isolated areas where access to health care may be limited, should be prioritized to receive initial doses of COVID-19 vaccines.” It is well established that Indigenous peoples disproportionately face poorer health outcomes, which includes Métis and Inuit, making them more vulnerable to COVID-19, which is why NACI made this recommendation. The rapid rise in cases in First Nations communities has already shown the need to prioritize vaccinations and we can see that working as the number of new cases continue to decline. This underscores the importance of tracking and sharing data for all Indigenous populations. -

The Saskatchewan Gazette, February 14, 2014 293 (Regulations)/Ce Numéro Ne Contient Pas De Partie Iii (Règlements)

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART III THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 14, 2014 293 (REGULATIONS)/CE NUMÉRO NE CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’ImPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 110 REGINA, FRIDAY, february 14, 2014/REGINA, VENDREDI, 14 FÉVRIER 2014 No. 7/nº 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAYS/JOURS SPÉCIAUX ................................................................................................................................................ 294 PROGRESS OF BILLS/RAPPORT SUR L’éTAT DES PROJETS DE LOI (Third Session, Twenty-Seventh Legislative Assembly/Troisième session, 27e Assemblée législative) ........................................... 294 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ..................................................................................... 295 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION (Third Session, Twenty-Seventh Legislative Assembly/Troisième session, 27e Assemblée législative) ........................................... 299 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES..... 299 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2013) ........................................................................................................................ 300 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2014) ....................................................................................................................... -

204-588-3236 October 13 - November 2, 2017 • V16N4 Senior Scope • 204-467-9000 • Kelly [email protected] Page 7

www.mobile.legal Donna Alden-Bugden, RN(NP), MN, DNP, Nurse Practitioner, Doctor of Nursing Practice ---------------------------------------- $80/visit + $40 for each additional patient FREE Join Senior Scope on: Cell/Text 204-770-2977 COPY Available in Winnipeg and suburbs Medical Care in the comforts of your Home http://NPCANADA.CA/DRUPAL8/HOUSECALLS Vol. 16 No. 4 Available in Winnipeg and rural Manitoba - over 700 locations Oct 13 - Nov 2/17 Get your copy at your local public library or read online at: www.seniorscope.com For info or advertising: 204-467-9000 | [email protected] 204 -691-7771 1320 Portage Avenue Leaf it to these folks Winnipeg MB Fall/Winter Collection ♦ Adaptive Pants ♦ Open-back Sweaters and Blouses to find fun with fall ♦ Undershirts & Nightwear ♦ Wheelchair Capes & Shawls ♦ Front-opening ♦ Slippers, Diabetic Friendly Socks FALL BACK... Promotion on Outfits: Top & Pants for $89 Daylight Saving Time in More offers available in store! Manitoba ends Nov. 5, 2017. Turn your clocks backward 1 hour Sunday, at 2:00 am to 1:00 am - to the local standard time. LAMB’S Window Cleaning Residential Eaves Cleaning Vinyl Siding Washing It was all good until the snow arrived... Diane (nee) Newman (centre), formerly of Stonewall, MB enjoying some fall fun with some friends in Calgary... before the snow hit early October! Diane: “They (Calgarians) say the weather changes every 15 minutes unlike Winnipeg. One day you can be all bundled up with winter gear and the next day you can be walking around with just a sweater on.” Photo courtesy of Mohdock Photography. -

Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties

Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties by Anju Gill B.A., University of the Fraser Valley, 2012 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Anju Gill 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2017 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Anju Gill Degree: Master of Arts Title: Discerning Claim Making: Political Representation of Indo-Canadians by Canadian Political Parties Examining Committee: Chair: Tsuyoshi Kawasaki Associate Professor Eline de Rooij Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Mark Pickup Supervisor Associate Professor Genevieve Fuji Johnson Internal/External Examiner Professor Date Defended/Approved: September 21, 2017 ii Abstract The targeting of people of colour by political parties during election campaigns is often described in the media as “wooing” or “courting.” How parties engage or “woo” non- whites is not fully understood. Theories on representation provide a framework for the systematic analysis of the types of representation claims made by political actors. I expand on the political proximity approach—which suggests that public office seekers make more substantive than symbolic claims to their partisans than to non-aligned voters—by arguing that Canadian political parties view mainstream voters as their typical constituents and visible minorities, such as Indo-Canadians, as peripheral constituents. Consequently, campaign messages targeted at mainstream voters include more substantive claims than messages targeted at non-white voters. -

BACKBENCHERS So in Election Here’S to You, Mr

Twitter matters American political satirist Stephen Colbert, host of his and even more SPEAKER smash show The Colbert Report, BACKBENCHERS so in Election Here’s to you, Mr. Milliken. poked fun at Canadian House Speaker Peter politics last week. p. 2 Former NDP MP Wendy Lill Campaign 2011. p. 2 Milliken left the House of is the writer behind CBC Commons with a little Radio’s Backbenchers. more dignity. p. 8 COLBERT Heard on the Hill p. 2 TWITTER TWENTY-SECOND YEAR, NO. 1082 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, APRIL 4, 2011 $4.00 Tories running ELECTION CAMPAIGN 2011 Lobbyists ‘pissed’ leaner war room, Prime Minister Stephen Harper on the hustings they can’t work on focused on election campaign, winning majority This campaign’s say it’s against their This election campaign’s war room Charter rights has 75 to 90 staffers, with the vast majority handling logistics of about one man Lobbying Commissioner Karen the Prime Minister’s tour. Shepherd tells lobbyists that working on a political By KRISTEN SHANE and how he’s run campaign advances private The Conservatives are running interests of public office holder. a leaner war room and a national campaign made up mostly of cam- the government By BEA VONGDOUANGCHANH paign veterans, some in new roles, whose goal is to persuade Canadi- Lobbyists are “frustrated” they ans to re-elect a “solid, stable Con- can’t work on the federal elec- servative government” to continue It’s a Harperendum, a tion campaign but vow to speak Canada’s economic recovery or risk out against a regulation that they a coalition government headed by national verdict on this think could be an unconstitutional Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff. -

Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act: a Proud Moment for Manitoba

The Enactment of Bill 5, The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act: A Proud Moment for Manitoba CONSTANCIA SMART - CARVALHO * I. INTRODUCTION 2018 CanLIIDocs 289 anada is a bilingual country in which English and French are constitutionally recognized as official languages.1 Language is an area in which both the federal and provincial governments can C 2 legislate and language regimes therefore vary from one province or territory to another.3 To date, every province except British Columbia has implemented some form of legislation, policy or regulatory framework with respect to French-language services.4 This article is focused on Bill 5, The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act,5 Manitoba’s recent legislative action concerning French-language rights. This legislation will be referred to as the “FCESA”, the “Bill”, and “Bill 5”. The FCESA is a significant achievement for Manitoba because it marks an important shift away from * B.A., J.D. The author of this article is articling at Thompson Dorfman Sweatman LLP in Winnipeg, Manitoba. 1 The Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, s 16. 2 Canada, Library of Parliament, “Language Regimes in the Provinces and Territories” by Marie-Eve Hudon, in Legal and Social Affairs Division, Publication No 2011-66-E (Ottawa: 6 January 2016) at 1 [Library of Parliament]. 3 Ibid. 4 Ibid. 5 The Francophone Community Enhancement and Support Act, SM 2016, c 9, s 1(2) [FCESA]. 480 MANITOBA LAW JOURNAL | VOLUME 41 ISSUE 1 a long history of political tensions surrounding language rights in the province. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

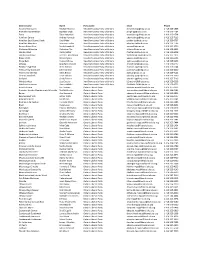

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson