The Gene Wars: Science, Politics, and the Human Genome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008

Copyright by Paul Harold Rubinson 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Paul Harold Rubinson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War Committee: —————————————————— Mark A. Lawrence, Supervisor —————————————————— Francis J. Gavin —————————————————— Bruce J. Hunt —————————————————— David M. Oshinsky —————————————————— Michael B. Stoff Containing Science: The U.S. National Security State and Scientists’ Challenge to Nuclear Weapons during the Cold War by Paul Harold Rubinson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Acknowledgements Thanks first and foremost to Mark Lawrence for his guidance, support, and enthusiasm throughout this project. It would be impossible to overstate how essential his insight and mentoring have been to this dissertation and my career in general. Just as important has been his camaraderie, which made the researching and writing of this dissertation infinitely more rewarding. Thanks as well to Bruce Hunt for his support. Especially helpful was his incisive feedback, which both encouraged me to think through my ideas more thoroughly, and reined me in when my writing overshot my argument. I offer my sincerest gratitude to the Smith Richardson Foundation and Yale University International Security Studies for the Predoctoral Fellowship that allowed me to do the bulk of the writing of this dissertation. Thanks also to the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, and John Gaddis and the incomparable Ann Carter-Drier at ISS. -

Medical Advisory Board September 1, 2006–August 31, 2007

hoWard hughes medical iNstitute 2007 annual report What’s Next h o W ard hughes medical i 4000 oNes Bridge road chevy chase, marylaNd 20815-6789 www.hhmi.org N stitute 2007 a nn ual report What’s Next Letter from the president 2 The primary purpose and objective of the conversation: wiLLiam r. Lummis 6 Howard Hughes Medical Institute shall be the promotion of human knowledge within the CREDITS thiNkiNg field of the basic sciences (principally the field of like medical research and education) and the a scieNtist 8 effective application thereof for the benefit of mankind. Page 1 Page 25 Page 43 Page 50 seeiNg Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Südhof: Paul Fetters; Fuchs: Janelia Farm lab: © Photography Neurotoxin (Brunger & Chapman): Page 3 Matthew Septimus; SCNT images: by Brad Feinknopf; First level of Rongsheng Jin and Axel Brunger; iN Bruce Weller Blake Porch and Chris Vargas/HHMI lab building: © Photography by Shadlen: Paul Fetters; Mouse Page 6 Page 26 Brad Feinknopf (Tsai): Li-Huei Tsai; Zoghbi: Agapito NeW Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Arabidopsis: Laboratory of Joanne Page 44 Sanchez/Baylor College 14 Page 8 Chory; Chory: Courtesy of Salk Janelia Farm guest housing: © Jeff Page 51 Ways Illustration by Riccardo Vecchio Institute Goldberg/Esto; Dudman: Matthew Szostak: Mark Wilson; Evans: Fred Page 10 Page 27 Septimus; Lee: Oliver Wien; Greaves/PR Newswire, © HHMI; Mello: Erika Larsen; Hannon: Zack Rosenthal: Paul Fetters; Students: Leonardo: Paul Fetters; Riddiford: Steitz: Harold Shapiro; Lefkowitz: capacity Seckler/AP, © HHMI; Lowe: Zack Paul Fetters; Map: Reprinted by Paul Fetters; Truman: Paul Fetters Stewart Waller/PR Newswire, Seckler/AP, © HHMI permission from Macmillan Page 46 © HHMI for Page 12 Publishers, Ltd.: Nature vol. -

2004 Albert Lasker Nomination Form

albert and mary lasker foundation 110 East 42nd Street Suite 1300 New York, ny 10017 November 3, 2003 tel 212 286-0222 fax 212 286-0924 Greetings: www.laskerfoundation.org james w. fordyce On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination Chairman neen hunt, ed.d. for the 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. President mrs. anne b. fordyce The Awards will be offered in three categories: Basic Medical Research, Clinical Medical Vice President Research, and Special Achievement in Medical Science. This is the 59th year of these christopher w. brody Treasurer awards. Since the program was first established in 1944, 68 Lasker Laureates have later w. michael brown Secretary won Nobel Prizes. Additional information on previous Lasker Laureates can be found jordan u. gutterman, m.d. online at our web site http://www.laskerfoundation.org. Representative Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards Program Nominations that have been made in previous years may be updated and resubmitted in purnell w. choppin, m.d. accordance with the instructions on page 2 of this nomination booklet. daniel e. koshland, jr., ph.d. mrs. william mccormick blair, jr. the honorable mark o. hatfied Nominations should be received by the Foundation no later than February 2, 2004. Directors Emeritus A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored. The 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards will be presented at a luncheon ceremony given by the Foundation in New York City on Friday, October 1, 2004. Sincerely, Joseph L. Goldstein, M.D. Chairman, Awards Jury Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards ALBERT LASKER MEDICAL2004 RESEARCH AWARDS PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE AWARDS The major purpose of these Awards is to recognize and honor individuals who have made signifi- cant contributions in basic or clinical research in diseases that are the main cause of death and disability. -

Anne Buckingham Young

BK-SFN-NEUROSCIENCE-131211-13_Young.indd 554 17/04/14 2:26 PM Anne Buckingham Young BORN: Evanston, Illinois December 30, 1947 EDUCATION: Vassar College, Summa Cum Laude, AB (1969) Johns Hopkins University Medical School, MD (1973) Johns Hopkins University Medical School, PhD (1974) APPOINTMENTS: Assistant, Full Professor of Neurology, University of Michigan (1978–1991) Julieanne Dorn Professor of Neurology, Harvard Medical School (1991–2012) Chief, Neurology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital (1991–2012) Distinguished Julieanne Dorn Professor of Neurology, Harvard Medical School (2012–present) HONORS AND AWARDS (SELECTED): Member, Institute of Medicine (1994) Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1995) Dean’s Award for Support and Advancement of Women Faculty, Harvard Medical School (1999) Marion Spence Faye Award for Women in Medicine (2001) President, American Neurological Association (2001–2003) President, Society for Neuroscience (2003–2004) Fellow, Royal College of Physicians, England (2005) Milton Wexler Award, Hereditary Disease Foundation (2006) Johns Hopkins Medical School Distinguished Alumni Award (2007) Vassar College Distinguished Alumni Award (2010) As a graduate student, Young provided the first biochemical evidence of glutamate as a neurotransmitter of the cerebellar granule cells. She developed biochemical techniques to measure inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitter receptors in the mammalian brain and spinal cord. As a faculty member at the University of Michigan, Young and her late husband (John B. Penney, Jr.) established the first biochemical data that glutamate was the neurotransmitter of the corticostriatal, corticobulbar, and corticospinal pathways. They developed film-based techniques for quantitative receptor autoradiography. They also provided evidence for their most widely cited model of basal ganglia function. -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast?

Mapping Our Genes—Genome Projects: How Big? How Fast? April 1988 NTIS order #PB88-212402 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Mapping Our Genes-The Genmne Projects.’ How Big, How Fast? OTA-BA-373 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1988). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 87-619898 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9325 (order form can be found in the back of this report) Foreword For the past 2 years, scientific and technical journals in biology and medicine have extensively covered a debate about whether and how to determine the function and order of human genes on human chromosomes and when to determine the sequence of molecular building blocks that comprise DNA in those chromosomes. In 1987, these issues rose to become part of the public agenda. The debate involves science, technol- ogy, and politics. Congress is responsible for ‘(writing the rules” of what various Federal agencies do and for funding their work. This report surveys the points made so far in the debate, focusing on those that most directly influence the policy options facing the U.S. Congress, The House Committee on Energy and Commerce requested that OTA undertake the project. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, the Senate Com- mittee on Labor and Human Resources, and the Senate Committee on Energy and Natu- ral Resources also asked OTA to address specific points of concern to them. Congres- sional interest focused on several issues: ● how to assess the rationales for conducting human genome projects, ● how to fund human genome projects (at what level and through which mech- anisms), ● how to coordinate the scientific and technical programs of the several Federal agencies and private interests already supporting various genome projects, and ● how to strike a balance regarding the impact of genome projects on international scientific cooperation and international economic competition in biotechnology. -

TPWKY This Is Exactly Right

TPWKY This is Exactly Right. Jay My name is Jay and I am 34 years old and I was recently diagnosed with Huntington's disease. My grandfather was diagnosed with Huntington's in his 80s but I don't think he and my grandmother really understood the severity of the illness and its implications for their children and grandchildren. So they never really told us until my father started seeing some symptoms in his 50s. So that's when I found out, I guess I was 28, I'd just been married, you know there's so much optimism and then I find out from my parents that there's this terrible shadow, you know, that's going to be potentially hanging over my life. And it was definitely really, really hard, I'm not gonna lie. Your priorities sort of shift, just trying to maximize the years that you might have with a good quality of life, you know. So I didn't get tested right away, I really wasn't ready. But over the years I started to I guess come to a point of acceptance and I also started to see symptoms starting to appear. Things like coordination issues, balance issues also, difficulty swallowing and drinking. So that's how it's starting to affect me and it got to a point where I was ready to be tested. And so I did that I guess a few months ago actually and now I have the official results that I am positive for Huntington's disease. At that point I guess it wasn't as bad as I thought actually to get those words. -

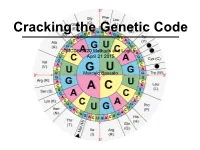

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

A Review of J. Craig Venter's a Life Decoded

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 17(1) – March 2008 A review of J. Craig Venter’s A Life Decoded Randy Mayes, Duke University Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 17 Issue 1 – March 2008 - pgs 71-72 http://jetpress.org/v17/mayes.htm In the early 1980s, a number of researchers suggested sequencing and mapping the human genome to help the science community better understand diseases and evolution. Following the announcement that the human genome had been sequenced, scientists wrote in peer-reviewed journals that we are not as hardwired as was once believed, and that the sequencing of the genome was just the beginning. Today, researchers have a new set of goals. In popular journalism, however, the science was lost in the shuffle. The media focused more on the dynamics of the conflicting philosophies of the private and public projects. This emphasis is also clear in the titles of several books chronicling the Human Genome Project, all appearing prior to the recent release of Craig Venter’s autobiography, A Life Decoded: My Genome: My Life (2007). Readers will find that Robert Cook-Deegan’s The Gene Wars (1995) and The Common Thread by Sir John Sulston and Georgina Ferry (2002), both written by insiders, are biased towards the philosophy of the public project, a commons approach. Sulston is a socialist who grows runner beans and drives a second hand car. By contrast, Venter travels in Lear jets and conducts business from his yacht. Three other books are more objective. -

Genetically Engineered Plants: a Potential Solution to Climate Change

Genetically Engineered Plants: A Potential Solution to Climate Change Dr Charles DeLisi GENETICALLY ENGINEERED PLANTS: A POTENTIAL SOLUTION TO CLIMATE CHANGE Climate change is already having devastating effects felt across the globe. Without adequate measures to counteract the human drivers behind climate change, these negative consequences are guaranteed to increase in severity in the coming decades. Esteemed biomedical scientist, Dr Charles DeLisi of Boston University, urges that a multi-disciplinary approach to mitigating climate change is vital. Using predictive modelling, he has demonstrated the potential power of genetically engineering plants to remove excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thereby mitigating climate change. ‘During the post-industrial period, the planetary temperature has increased rapidly,’ explains Dr Charles DeLisi of Boston University. ‘Ice sheet melting has accelerated, ocean levels have risen with concomitant increases in coastal flooding, and extreme weather events have increased in frequency.’ Emissions Reductions: Not the Whole Solution Thus far, measures to tackle climate change have focused on reducing our emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Over the last three The Climate Emergency These changes are driven by increasing decades, over 100 nations across the levels of atmospheric ‘greenhouse globe have signed multiple agreements Climate change is, arguably, the most gases’, such as carbon dioxide. Released to voluntarily limit their emissions, significant global threat that society as a by-product of fossil fuel combustion but these measures alone are proving faces. Even small perturbations and other human activities, the level ineffective at slowing climatic in the planet’s climatic system of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere disruption. -

The Gene Wars: Science, Politics, and the Human Genome

8 Early Skirmishes | N A COMMENTARY introducing the March 7, 1986, issue of Science, I. Renato Dulbecco, a Nobel laureate and president of the Salk Institute, made the startling assertion that progress in the War on Cancer would be speedier if geneticists were to sequence the human genome.1 For most biologists, Dulbecco's Science article was their first encounter with the idea of sequencing the human genome, and it provoked discussions in the laboratories of universities and research centers throughout the world. Dul- becco was not known as a crusader or self-promoter—quite the opposite— and so his proposal attained credence it would have lacked coming from a less esteemed source. Like Sinsheimer, Dulbecco came to the idea from a penchant for thinking big. His first public airing of the idea came at a gala Kennedy Center event, a meeting organized by the Italian embassy in Washington, D.C., on Columbus Day, 1985.2 The meeting included a section on U.S.-Italian cooperation in science, and Dulbecco was invited to give a presentation as one of the most eminent Italian biologists, familiar with science in both the United States and Italy. He was preparing a review paper on the genetic approach to cancer, and he decided that the occasion called for grand ideas. In thinking through the recent past and future directions of cancer research, he decided it could be greatly enriched by a single bold stroke—sequencing the human genome. This Washington meeting marked the beginning of the Italian genome program.3 Dulbecco later made the sequencing