Preliminary Documentary Report on Benedict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redemption Found Believers Can Trust God to Be Faithful to Them

Session 3 | Job 19:19-29 Redemption Found Believers can trust God to be faithful to them. New York’s Saratoga National Historical Park contains an unusual statue. It is a stone monument featuring a military commander’s single boot. The monument’s inscription lauds but does not name the “most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army” who received a severe leg wound at the Battle of Saratoga. The unnamed commander’s hard-hitting attack at Saratoga routed the British army and assured an American victory in the battle. That victory helped convince France to enter the Revolutionary War on the side of the American colonies. French support ultimately tipped the scales in the Continental Army’s favor, leading to America’s long-sought independence. The boot monument pays tribute to this unnamed colonial soldier’s leg wound received while leading a final, victorious charge. So why has this man been denied the mark of respect due a military hero? Why was the commander’s name not engraved on the monument that honored his valor? The answer is because the soldier’s name was Benedict Arnold, a name that has become synonymous with treason. By the early summer of 1780, Arnold was a recognized national hero. He held the rank of Major General in the United States Army and had an unrivaled war record. George Washington considered Arnold to be one of his most dependable military leaders and named him the commander of the critical fort at West Point, New York. Regrettably, it was there that a disgruntled Arnold entered into secret negotiations with the British army to surrender the fort. -

According to Wikipedia 2011 with Some Addictions

American MilitMilitaryary Historians AAA-A---FFFF According to Wikipedia 2011 with some addictions Society for Military History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Society for Military History is an United States -based international organization of scholars who research, write and teach military history of all time periods and places. It includes Naval history , air power history and studies of technology, ideas, and homefronts. It publishes the quarterly refereed journal titled The Journal of Military History . An annual meeting is held every year. Recent meetings have been held in Frederick, Maryland, from April 19-22, 2007; Ogden, Utah, from April 17- 19, 2008; Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2-5 April 2009 and Lexington, Virginia 20-23 May 2010. The society was established in 1933 as the American Military History Foundation, renamed in 1939 the American Military Institute, and renamed again in 1990 as the Society for Military History. It has over 2,300 members including many prominent scholars, soldiers, and citizens interested in military history. [citation needed ] Membership is open to anyone and includes a subscription to the journal. Officers Officers (2009-2010) are: • President Dr. Brian M. Linn • Vice President Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar • Executive Director Dr. Robert H. Berlin • Treasurer Dr. Graham A. Cosmas • Journal Editor Dr. Bruce Vandervort • Journal Managing Editors James R. Arnold and Roberta Wiener • Recording Secretary & Photographer Thomas Morgan • Webmaster & Newsletter Editor Dr. Kurt Hackemer • Archivist Paul A. -

Notes on Contributors 7 6 7

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 7 6 7 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS ALLEN, Walter. Novelist and Literary Critic. Author of six novels (the most recent being All in a Lifetime, 1959); several critical works, including Arnold Bennett, 1948; Reading a Novel, 1949 (revised, 1956); Joyce Cary, 1953 (revised, 1971); The English Novel, 1954; Six Great Novelists, 1955; The Novel Today, 1955 (revised, 1966); George Eliot, 1964; and The Modern Novel in Britain and the United States, 1964; and of travel books, social history, and books for children. Editor of Writers on Writing, 1948, and of The Roaring Queen by Wyndham Lewis, 1973. Has taught at several universities in Britain, the United States, and Canada, and been an editor of the New Statesman. Essays: Richard Hughes; Ring Lardner; Dorothy Richardson; H. G. Wells. ANDERSON, David D. Professor of American Thought and Language, Michigan State University, East Lansing; Editor of University College Quarterly and Midamerica. Author of Louis Bromfield, 1964; Critical Studies in American Literature, 1964; Sherwood Anderson, 1967; Anderson's "Winesburg, Ohio," 1967; Brand Whitlock, 1968; Abraham Lincoln, 1970; Robert Ingersoll, 1972; Woodrow Wilson, 1975. Editor or Co-Editor of The Black Experience, 1969; The Literary Works of Lincoln, 1970; The Dark and Tangled Path, 1971 ; Sunshine and Smoke, 1971. Essay: Louis Bromfield. ANGLE, James. Assistant Professor of English, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti. Author of verse and fiction in periodicals, and of an article on Edward Lewis Wallant in Kansas Quarterly, Fall 1975. Essay: Edward Lewis Wallant. ASHLEY, Leonard R.N. Professor of English, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. Author of Colley Cibber, 1965; 19th-Century British Drama, 1967; Authorship and Evidence: A Study of Attribution and the Renaissance Drama, 1968; History of the Short Story, 1968; George Peele: The Man and His Work, 1970. -

RAO Bulletin Update 15 Oct 2007

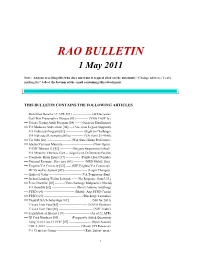

RAO BULLETIN 1 May 2011 Note: Anyone receiving this who does not want it request click on the automatic “Change address / Leave mailing list” tab at the bottom of the email containing this attachment. ================================================================================== THIS BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES == Mobilized Reserve 19 APR 2011 ----------------- (42 Decrease) == Gulf War Presumptive Disease [03] ----------- (VBA FAST ltr) == Tricare Young Adult Program [04] ----- (Open for Enrollment) == VA Medicare Subvention [04] --- (American Legion Supports) == VA Fiduciary Program [01] ---------------- (Right to Challenge) == VA Individual Unemployability ----------- (VA Form 21-4140) == Vet Jobs [26] ---------------------- (WA State Hiring Preference) == Alaska Veterans Museum --------------------------- (Now Open) == VAMC Marion IL [02] ----------- (Surgery Suspension Lifted) == VA Minority Veterans Care -- (Significant Differences Persist) == Traumatic Brain Injury [17] ------------- (Purple Heart Denials) == National Resource Directory [01] ---------- (NRD Mobile Site) == Virginia Vet Cemetery [02] ----- (SW Virginia Vet Cemetery) == DFAS myPay System [09] --------------------- (Login Changes) == Quilts of Valor ----------------------------- (VA Temporary Ban) == Inchon Landing Wolmi Lawsuit ----- (No Response from U.S.) == Feres Doctrine [03] -------- (Vets challenge Malpractice Shield) == VA Benefits [02] ---------------------- (Don‘t Assume Anything) == PTSD [64] ---------------------------- (Mobile App PTSD -

Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland During the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775

Maine History Volume 47 Number 1 The Maine Borderlands Article 4 1-1-2013 “News of Provisions Ahead”: Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland during the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775 Daniel S. Soucier Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Geography Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S.. "“News of Provisions Ahead”: Accommodation in a Wilderness Borderland during the American Invasion of Quebec, 1775." Maine History 47, 1 (2013): 42-67. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Benedict Arnold led an invasion of Quebec during the first year of the Revolu - tionary War. Arnold was an ardent Patriot in the early years of the war, but later became the most famous American turncoat of the era. Maine Historical Soci - ety Collections. “NEWS OF PROVISIONS AHEAD”: ACCOMMODATION IN A WILDERNESS BORDERLAND DURING THE AMERICAN INVASION OF QUEBEC, 1775 1 BY DANIEL S. S OUCIER Soon after the American Revolutionary War began, Colonel Benedict Arnold led an American invasion force from Maine into Quebec in an ef - fort to capture the British province. The trek through the wilderness of western Maine did not go smoothly. This territory was a unique border - land area that was not inhabited by colonists as a frontier society, but in - stead remained a largely unsettled region still under the control of the Wabanakis. -

Wine List Intro.Docx

Supplement to Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues This book list, together with my Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues (1996-2002) represents, to the best of my reconstructive ability, the complete collection built over a roughly twenty-year period ending in 1982. The Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues had been drawn from books that suffered fire and water torture in 1979. The present list also includes books acquired before and after that event, while we were living in Italy, and before I reluctantly rejected the idea of rebuilding the collection. A few of these later acquisitions were offered for sale in the catalogues, but most of them remain in my possession. They are identified here with the note “[**++].” The following additional identifiers are used in this list: [**ici] – “incomplete cataloguing information” available – “short title” detail at best. All of these books were lost or discarded. [**sold] – books sold prior to the Wine & Gastronomy series, including from my Catalogue 1, issued March 1990. [**kept] – includes bibliographies, reference books, and books on coffee, tea and chocolate, and a few others which escaped inclusion in the catalogues. All items not otherwise identified were lost or discarded. The list includes a number of wine maps, but there were a few others for which there wasn’t enough information available to justify inclusion. To the list of wine bibliographies consulted for the Wine & Gastronomy catalogues, I would like to add the extensive German bibliography by Renate Schoene, first published in 1978 as Bibliographie zur Geschichte des Weines (Mannheim, 1976), followed by three supplements (1978, 1982, 1984), and the second edition (München, 1988). -

The Work of Kenneth Roberts

Colby Quarterly Volume 6 Issue 3 September Article 4 September 1962 The Work of Kenneth Roberts Herbert Faulkner West Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, series 6, no.3, September 1962, p.89-99 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. West: The Work of Kenneth Roberts Colby Library Quarterly 89 launched the 'Peon Corporation' among the Abercrombies and the Fitches in New York; or the triumphant afternoon in Nas sau when we persuaded a colored boy to teach you and me the trick of sculling a boat; and, most particularly of course, the adventures without number in Rocky Pasture itself, whose door has always been open ... and still is ... and through which, obviously, you constantly come walking in again ... One is very much aware of you, Ken. Yours ever, Arthur THE WORK O'F KENNETH ROBERTS By HERBERT FAULKNER WEST I T is difficult to assess an author's real worth until several years after his death, and even then it is not an easy task. Quite frequently (and often wrongly) an author's reputation drops considerably after his death, as was the case, for instance, with Arnold Bennett, H. G. Wells, and even as good a writer as John Galsworthy. Time, however, ultimately seems to win now the wheat from the chaff. Kenneth Roberts, born in 1885, died about five years ago, in 1957. -

Social Studies 7: Inquiry Based Lesson Compelling Question: Should a Traitor Be Erased from History?

Social Studies 7: Inquiry Based Lesson Compelling Question: Should a traitor be erased from history? Using primary and secondary sources students will participate in a day long activity where they will culminate in making the decision of whether or not Benedict Arnold has earned his place on the Saratoga Monument and if he should be named on the boot monument. Anticipatory Set (5 minutes) Begin the class by displaying the two attached websites and reading through them with the class Visit the attached website to read the background on the famous monument to Arnold’s leg: http://www.pbs.org/ktca/liberty/popup_arnoldsleg.html Visit the attached website to read the background on the Saratoga Monument: http://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/photosmultimedia/saratoga-monument-virtual-tour-part-3.htm Print out enough of the images for each student to have one. Pass out the images of the two different monuments. Stations Activity (35 minutes) Set up your classroom with five different stations. One will need to have access to electronic equipment able to play a youtube video clip. Print out enough copies of each of the stations activity information sheets for each student to have one to look at when they are at the station. (Class of 20, 5 stations, 4 copies needed) Label the stations with numbers and put the copies in the middle of the table. Print out enough of the questions packets for each student to have one. Set up a timer where students will have roughly 7 minutes at each station. If they aren’t quite finished, have them move along anyway. -

Boot Monument - Wikipedia

Boot Monument - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_Monument Coordinates: 43.008535°N 73.639598°W The Boot Monument is an American Revolutionary War memorial located in Saratoga National Historical Park, New York. It commemorates Major General Benedict Arnold's service at the Battles of Saratoga in the Continental Army, but does not name him. Background Arnold's perceived offenses References Sources External links John Watts de Peyster, a former Major General for the New York State Militia during the American Civil War and writer of several military histories about the Battle of Saratoga, erected the monument to commemorate Arnold's contribution to the Continental Army's victory over the British. Arnold was wounded in the foot during the Battle of Monument to Benedict Arnold's injured foot at Quebec, and suffered further injury in the Battle of Ridgefield Saratoga National Historical Park when his horse was shot out from under him. His last battle injury was at Saratoga, and it occurred near where this monument is located at Tour Stop #7 – Breymann Redoubt. The leg wound effectively ended his career as a fighting soldier. It reads: Erected 1887 By JOHN WATTS de PEYSTER Brev: Maj: Gen: S.N.Y. 2nd V. Pres't Saratoga Mon't Ass't'n: In memory of the "most brilliant soldier" of the Continental Army who was desperately wounded on this spot the sally port of BURGOYNES GREAT WESTERN REDOUBT 1 of 3 9/24/2019, 4:11 PM Boot Monument - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_Monument 7th October, 1777 winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution and for himself the rank of Major General. -

Why American History Is Not What They Say

WHY AMERICAN HISTORY IS NOT WHAT THEY SAY: AN INTRODUCTION TO REVISIONISM also by jeff riggenbach In Praise of Decadence WHY AMERICAN HISTORY IS NOT WHAT THEY SAY: AN INTRODUCTION TO REVISIONISM Jeff Riggenbach Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832; mises.org. Copyright 2009 © by Jeff Riggenbach Published under Creative Commons attribution license 3.0 ISBN: 978-1-933550-49-7 History, n. An account mostly false, of events mostly unimportant, which are brought about by rulers mostly knaves, and soldiers mostly fools. —ambrose bierce The Devil’s Dictionary (1906) This book is for Suzanne, who made it possible. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Portions of Chapter Three and Chapter Five appeared earlier, in somewhat different form, in Liberty magazine, on RationalReview. com, and on Antiwar.com. David J. Theroux of the Independent Institute, Andrea Millen Rich of the Center for Independent Thought, and Alexia Gilmore of the Randolph Bourne Institute were generous with their assistance during the researching and writing stages of this project. Ellen Stuttle was her usual indispensable self. And, of course, responsibility for any errors of fact, usage, or judgment in these pages is entirely my own. CONTENTS preface 15 one The Art of History 19 i. Objectivity in History 19 ii. History and Fiction 25 iii. Th e Historical Fiction of Kenneth Roberts 36 iv. Th e Historical Fiction of John Dos Passos 41 two The Historical Fiction of Gore Vidal: The “American Chronicle” Novels 49 i. Burr and Lincoln 49 ii. 1876, Empire, and Hollywood 59 iii. Hollywood and Th e Golden Age 65 three The Story of American Revisionism 71 i. -

History

~~~~~~~!tt~~~~~ . ~ NEW SERIES : Pm, , doll", : VOL. xX'" No. 1 ~ IVERMONT i ~ History ~ ~ Formerly the Vmnont Quarterly ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ July 1956 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ht <PRoceeDINGS oftht @ ~ VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIEIT ~ ~~~~~~~~~@ THE WHITE CHIEF OF THE ST. FRANCIS ABNAKIS-SOME ASPECTS OF BORDER WARFARE: 1690-1790 By JOHN C. HUDEN University of vermont This study is the fourth in a series by Dr. Ruden, beginning with the January, 1955, quarterly. The general theme has to do with the neglected lnditm phase of Vermont history and indirectly with the early relationships between Canada and Vermont. The studies should be, at this point, regarded as exploratory in character. The generous w-opercrtion of Canadian sclwlars and officials has made these studies possible. Acknowledgements in full will he made later. Editor. LTHOUGH our story is mainly concerned with Joseph-Louis Gill, A the White Chief of St. Francis, it really begins in June 1697 at Salisbury, Massachusetts, where a ten-year old boy named Samuel Gill was captured by Abnakis and brought back with them to their Canadian fort, Odanak, [see map] near the mouth of the St. Francis River. Some time later a little girl known to us only as "Miss James" was taken prisoner at Kennebunk, Maine; she, too, was carried away to Odanak. Both children were adopted by Indians, baptized in the Roman Catholic faith, brought up in the Indian manner, and remained with the tribe for the rest of their lives. They were married [probably around 1715] by the venerable missionary, Father Aubery. According to one of their descendants, Judge Charles GilJ,! Samuel was probably not living in 1754 as Mrs. -

Proceedings® of the International Symposium Heritage for Planet Earth 2018

PROCEEDINGS® OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HERITAGE FOR PLANET EARTH 2018 TH 1998 20 2018 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS & SYMPOSIUM HERITAGE FOR PLANET EARTH® 2018 PATRONAGES INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS UNIVERSITIES & ACADEMIES OTHER INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS WFUCA FICLU United Nations Federazione Italiana Educational, Scientific and dei Club e Centri Cultural Organization per l’UNESCO Centro per l’UNESCO di Firenze con il patrocinio di CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI FIRENZE INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS OTHER INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS • Commissione Nazionale Italiana per UNESCO (Italy) • Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage (ARC-WH) under the auspices of UNESCO • APAB Istituto di Formazione (Italy) • ETOA - European Tourism Association • Associazione d’Agricoltura Biodinamica (Italy) • ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites • Archiva (Italy) • ICCROM - Centro internazionale di studi per la conservazione • Associazione Siti Italiani UNESCO (Italy) ed il restauro dei beni culturali • Bandierai degli Uffizi (Italy) • UCLG United Cities and Local Governments of Africa • Centro UNESCO Firenze (Italy) UNIVERSITIES & ACADEMIES • Centro UNESCO Torino (Italy) • Academy of Fine Arts in Lodz (Poland) • Città di Figline e Incisa Valdarno (Italy) • Azerbaijan Univerisity of Architecture and Construction • Città Metropolitana Firenze (Italy) (Azerbaijan) • Confcommercio Firenze (Italy) • Balikesir University (Turkey) • Comune di Firenze (Italy) • Bydgoszcz Music Academy (Poland) • Comune di Regello (Italy) • CIRT - Centro