Fall-Winter 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redemption Found Believers Can Trust God to Be Faithful to Them

Session 3 | Job 19:19-29 Redemption Found Believers can trust God to be faithful to them. New York’s Saratoga National Historical Park contains an unusual statue. It is a stone monument featuring a military commander’s single boot. The monument’s inscription lauds but does not name the “most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army” who received a severe leg wound at the Battle of Saratoga. The unnamed commander’s hard-hitting attack at Saratoga routed the British army and assured an American victory in the battle. That victory helped convince France to enter the Revolutionary War on the side of the American colonies. French support ultimately tipped the scales in the Continental Army’s favor, leading to America’s long-sought independence. The boot monument pays tribute to this unnamed colonial soldier’s leg wound received while leading a final, victorious charge. So why has this man been denied the mark of respect due a military hero? Why was the commander’s name not engraved on the monument that honored his valor? The answer is because the soldier’s name was Benedict Arnold, a name that has become synonymous with treason. By the early summer of 1780, Arnold was a recognized national hero. He held the rank of Major General in the United States Army and had an unrivaled war record. George Washington considered Arnold to be one of his most dependable military leaders and named him the commander of the critical fort at West Point, New York. Regrettably, it was there that a disgruntled Arnold entered into secret negotiations with the British army to surrender the fort. -

According to Wikipedia 2011 with Some Addictions

American MilitMilitaryary Historians AAA-A---FFFF According to Wikipedia 2011 with some addictions Society for Military History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Society for Military History is an United States -based international organization of scholars who research, write and teach military history of all time periods and places. It includes Naval history , air power history and studies of technology, ideas, and homefronts. It publishes the quarterly refereed journal titled The Journal of Military History . An annual meeting is held every year. Recent meetings have been held in Frederick, Maryland, from April 19-22, 2007; Ogden, Utah, from April 17- 19, 2008; Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2-5 April 2009 and Lexington, Virginia 20-23 May 2010. The society was established in 1933 as the American Military History Foundation, renamed in 1939 the American Military Institute, and renamed again in 1990 as the Society for Military History. It has over 2,300 members including many prominent scholars, soldiers, and citizens interested in military history. [citation needed ] Membership is open to anyone and includes a subscription to the journal. Officers Officers (2009-2010) are: • President Dr. Brian M. Linn • Vice President Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar • Executive Director Dr. Robert H. Berlin • Treasurer Dr. Graham A. Cosmas • Journal Editor Dr. Bruce Vandervort • Journal Managing Editors James R. Arnold and Roberta Wiener • Recording Secretary & Photographer Thomas Morgan • Webmaster & Newsletter Editor Dr. Kurt Hackemer • Archivist Paul A. -

RAO Bulletin Update 15 Oct 2007

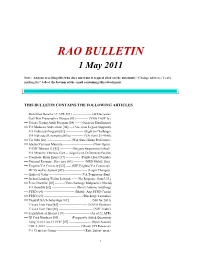

RAO BULLETIN 1 May 2011 Note: Anyone receiving this who does not want it request click on the automatic “Change address / Leave mailing list” tab at the bottom of the email containing this attachment. ================================================================================== THIS BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES == Mobilized Reserve 19 APR 2011 ----------------- (42 Decrease) == Gulf War Presumptive Disease [03] ----------- (VBA FAST ltr) == Tricare Young Adult Program [04] ----- (Open for Enrollment) == VA Medicare Subvention [04] --- (American Legion Supports) == VA Fiduciary Program [01] ---------------- (Right to Challenge) == VA Individual Unemployability ----------- (VA Form 21-4140) == Vet Jobs [26] ---------------------- (WA State Hiring Preference) == Alaska Veterans Museum --------------------------- (Now Open) == VAMC Marion IL [02] ----------- (Surgery Suspension Lifted) == VA Minority Veterans Care -- (Significant Differences Persist) == Traumatic Brain Injury [17] ------------- (Purple Heart Denials) == National Resource Directory [01] ---------- (NRD Mobile Site) == Virginia Vet Cemetery [02] ----- (SW Virginia Vet Cemetery) == DFAS myPay System [09] --------------------- (Login Changes) == Quilts of Valor ----------------------------- (VA Temporary Ban) == Inchon Landing Wolmi Lawsuit ----- (No Response from U.S.) == Feres Doctrine [03] -------- (Vets challenge Malpractice Shield) == VA Benefits [02] ---------------------- (Don‘t Assume Anything) == PTSD [64] ---------------------------- (Mobile App PTSD -

Social Studies 7: Inquiry Based Lesson Compelling Question: Should a Traitor Be Erased from History?

Social Studies 7: Inquiry Based Lesson Compelling Question: Should a traitor be erased from history? Using primary and secondary sources students will participate in a day long activity where they will culminate in making the decision of whether or not Benedict Arnold has earned his place on the Saratoga Monument and if he should be named on the boot monument. Anticipatory Set (5 minutes) Begin the class by displaying the two attached websites and reading through them with the class Visit the attached website to read the background on the famous monument to Arnold’s leg: http://www.pbs.org/ktca/liberty/popup_arnoldsleg.html Visit the attached website to read the background on the Saratoga Monument: http://www.nps.gov/sara/learn/photosmultimedia/saratoga-monument-virtual-tour-part-3.htm Print out enough of the images for each student to have one. Pass out the images of the two different monuments. Stations Activity (35 minutes) Set up your classroom with five different stations. One will need to have access to electronic equipment able to play a youtube video clip. Print out enough copies of each of the stations activity information sheets for each student to have one to look at when they are at the station. (Class of 20, 5 stations, 4 copies needed) Label the stations with numbers and put the copies in the middle of the table. Print out enough of the questions packets for each student to have one. Set up a timer where students will have roughly 7 minutes at each station. If they aren’t quite finished, have them move along anyway. -

Boot Monument - Wikipedia

Boot Monument - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_Monument Coordinates: 43.008535°N 73.639598°W The Boot Monument is an American Revolutionary War memorial located in Saratoga National Historical Park, New York. It commemorates Major General Benedict Arnold's service at the Battles of Saratoga in the Continental Army, but does not name him. Background Arnold's perceived offenses References Sources External links John Watts de Peyster, a former Major General for the New York State Militia during the American Civil War and writer of several military histories about the Battle of Saratoga, erected the monument to commemorate Arnold's contribution to the Continental Army's victory over the British. Arnold was wounded in the foot during the Battle of Monument to Benedict Arnold's injured foot at Quebec, and suffered further injury in the Battle of Ridgefield Saratoga National Historical Park when his horse was shot out from under him. His last battle injury was at Saratoga, and it occurred near where this monument is located at Tour Stop #7 – Breymann Redoubt. The leg wound effectively ended his career as a fighting soldier. It reads: Erected 1887 By JOHN WATTS de PEYSTER Brev: Maj: Gen: S.N.Y. 2nd V. Pres't Saratoga Mon't Ass't'n: In memory of the "most brilliant soldier" of the Continental Army who was desperately wounded on this spot the sally port of BURGOYNES GREAT WESTERN REDOUBT 1 of 3 9/24/2019, 4:11 PM Boot Monument - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_Monument 7th October, 1777 winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution and for himself the rank of Major General. -

Proceedings® of the International Symposium Heritage for Planet Earth 2018

PROCEEDINGS® OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM HERITAGE FOR PLANET EARTH 2018 TH 1998 20 2018 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS & SYMPOSIUM HERITAGE FOR PLANET EARTH® 2018 PATRONAGES INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS UNIVERSITIES & ACADEMIES OTHER INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS WFUCA FICLU United Nations Federazione Italiana Educational, Scientific and dei Club e Centri Cultural Organization per l’UNESCO Centro per l’UNESCO di Firenze con il patrocinio di CITTÀ METROPOLITANA DI FIRENZE INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS OTHER INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS • Commissione Nazionale Italiana per UNESCO (Italy) • Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage (ARC-WH) under the auspices of UNESCO • APAB Istituto di Formazione (Italy) • ETOA - European Tourism Association • Associazione d’Agricoltura Biodinamica (Italy) • ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and Sites • Archiva (Italy) • ICCROM - Centro internazionale di studi per la conservazione • Associazione Siti Italiani UNESCO (Italy) ed il restauro dei beni culturali • Bandierai degli Uffizi (Italy) • UCLG United Cities and Local Governments of Africa • Centro UNESCO Firenze (Italy) UNIVERSITIES & ACADEMIES • Centro UNESCO Torino (Italy) • Academy of Fine Arts in Lodz (Poland) • Città di Figline e Incisa Valdarno (Italy) • Azerbaijan Univerisity of Architecture and Construction • Città Metropolitana Firenze (Italy) (Azerbaijan) • Confcommercio Firenze (Italy) • Balikesir University (Turkey) • Comune di Firenze (Italy) • Bydgoszcz Music Academy (Poland) • Comune di Regello (Italy) • CIRT - Centro -

Saratoga 1777: the Crucible

special section: Upstate n.Y. Battlefields “British 10th Foot Light Infantry Charging no. 1” Saratoga 1777: (ref. 18014). The Crucible James H. Hillestad draws inspiration from the turning point of the American Revolution to deploy W. Britain figures in a diorama Text and Photos: James H. Hillestad n invitation to a good friend’s Princeton in New Jersey. defeat the Northern Department of the wedding last fall at Lake George, Responding to these major setbacks, American Army. He would then go on to AN.Y., expanded into a side trip to British Gen. John Burgoyne, Carleton’s invade New England and reoccupy Boston, the Saratoga National Historical Park, second in command, proposed an the hotbed of revolutionary sentiment. which in turn inspired an American ambitious plan to King George III and Revolutionary War battlefield diorama. Lord Germain, the secretary of state for THE PLAN UNFOLDS !e focus was the pivotal clash at America. Burgoyne wanted to attack the All went well, at first. Freeman’s Farm during the Battles of Americans in a way that would isolate American-held Fort Ticonderoga Saratoga. New England from the other colonies. commanded the Lake Champlain/Lake I used 1:32-scale, matt-finished He promoted his plan without either the George waterway corridor extending figures and scenic accessories from W. knowledge or the concurrence of Howe. from the St. Lawrence River to the north Britain to re-create the clash in miniature. to the Hudson River to the south. After !e toy soldiers recruited for the scene CAMPAIGN PLAN Burgoyne’s soldiers took command of included British 10th Foot Light Infantry “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne’s campaign high ground with artillery and nearly pitted against Colonial militiamen and plan called for a three-pronged invasion surrounded the Americans’ defenses, Continental Line Infantry of New York/ of New York by British armies operating fort commander Gen. -

Benedict Arnold - Wikipedia

Benedict Arnold - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_Arnold Benedict Arnold (January 14, 1741 [O.S. January Benedict Arnold 3, 1740][1][2] – June 14, 1801) was an American military officer who served as a general during the American Revolutionary War, fighting for the American Continental Army before defecting to the British in 1780. George Washington had given him his fullest trust and placed him in command of the fortifications at West Point, New York. Arnold planned to surrender the fort to British forces, but the plot was discovered in September 1780 and he fled to the British. His name quickly became a byword in the United States for treason and betrayal because he led the British army in battle against the very men whom he had once commanded.[3] Arnold was born in the Connecticut Colony and was Arnold in American uniform, engraved by H. B. Hall, after a merchant operating ships on the Atlantic Ocean John Trumbull when the war began in 1775. He joined the growing Born January 14, 1741 army outside Boston and distinguished himself Norwich, Connecticut Colony through acts of intelligence and bravery. His actions Died June 14, 1801 (aged 60) included the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga in 1775, London, United Kingdom defensive and delaying tactics at the Battle of Buried St Mary's Church, Battersea, London Valcour Island on Lake Champlain in 1776 which allowed American forces time to prepare New York's Allegiance United States (1775–1780) defenses, the Battle of Ridgefield, Connecticut (after Kingdom of Great Britain / British which he was promoted to major general), Empire (1780–1781) operations in relief of the Siege of Fort Stanwix, and Service/ Colonial militia key actions during the pivotal Battles of Saratoga in branch Continental Army 1777, in which he suffered leg injuries that halted his combat career for several years. -

Battles of Saratoga - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Battles of Saratoga - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Saratoga Coordinates: 42°59′56″N 73°38′15″W Battles of Saratoga From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne led a large invasion army up the Champlain Valley Battles of Saratoga from Canada, hoping to meet a similar force marching northward from New York City; the southern force never arrived, and Burgoyne was Part of the American Revolutionary War surrounded by American forces in upstate New York. Burgoyne fought two small battles to break out. They took place eighteen days apart on the same ground, 9 miles (14 km) south of Saratoga, New York. They both failed. Trapped by superior American forces, with no relief in sight, Burgoyne surrendered his entire army on October 17. His surrender, says historian Edmund Morgan, "was a great turning point of the war, because it won for Americans the foreign assistance which was the last element needed for victory.[8] Burgoyne's strategy to divide New England from the southern colonies had started well, but slowed due to logistical problems. He won a small tactical victory over General Horatio Gates and the Continental Army in the September 19 Battle of Freeman's Farm at the cost of significant casualties. His gains were erased when he again attacked the Americans in the October 7 Battle of Bemis Heights and the Americans captured a portion of the British defenses. -

Interpretive Prospectus SARATOGA

interpretive prospectus 3'7V/>3 3/5"3- SARATOGA NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK • NEW YORK INTERPRETIVE PROSPECTUS Saratoga National Historical Park august 1970 S/ \ recommended irector ■ IVE Region "Nor can any military event be said to have exercised more important influence upon the fortunes of mankind than the complete defeat of Burgoyne's expedition in 1777; a defeat which rescued the revolted colonists from certain subjection; and which, by inducing the Courts of France and Spain to attack England in their behalf, insured the independence of the United Stated'.’ Sir Edward Creasy TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.................. .............................. 1 The Significance of Saratoga................................. 3 The Visitor Experience . ................................ 6 Interpretive Objectives .................................... 8 Interpretive Considerations........ ' ........................ 10 Summary of Existing Facilities .............................. 11 Proposed Interpretive Development .......................... 14 The Visitor Center...................................... 16 The Tour R o a d ...........................................27 The Champlain C a n a l .................................... 42 Bemis T a v e r n .......................................... 44 The Schuyler Property.................................. 45 Publications ................................................ 50 Personnel and Staffing . ................................. 52 Other Considerations........................................ 55 Museum Collection.......................................55 -

Battles of Saratoga - Wikipedia

Battles of Saratoga - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Saratoga Battles of Saratoga Coordinates: 42°59′56″N 73°38′15″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) marked the climax of the Saratoga campaign giving a decisive victory to the Americans over the British in the American Revolutionary War. British General John Burgoyne Battles of Saratoga led a large invasion army southward in the Champlain Valley from Canada, hoping to meet a similar force marching Part of the American Revolutionary War northward from New York City, and another force marching eastward from Lake Ontario; the southern and western Saratoga campaign forces never arrived, and Burgoyne was surrounded by American forces in upstate New York. Burgoyne fought two small battles to break out. They took place eighteen days apart on the same ground, 9 miles (14 km) south of Saratoga, New York. They both failed. Trapped by superior American forces, and with no relief in sight, Burgoyne retreated to Saratoga (now Schuylerville) and surrendered his entire army there on October 17. His surrender, says historian Edmund Morgan, "was a great turning point of the war because it won for Americans the foreign assistance which was the last element needed for victory.[8] Burgoyne's strategy to divide New England from the southern colonies had started well but slowed due to logistical problems. He won a small tactical victory over General Horatio Gates and the Continental Army in the September 19 Battle of Freeman's Farm at the cost of significant casualties. -

Saratoga National Historical Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Saratoga National Historical Park Draft General Management Plan Draft Environmental Impact Statement 2003 Saratoga National Historical Park STILLWATER AND SARATOGA, NEW YORK Draft General Management Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement Prepared by: Northeast Region, Boston Office Saratoga National Historical Park 2003 “At Saratoga, the British campaign that was supposed to crush America’s rebellion ended instead in a surrender that changed the history of the world.” Richard Ketchum Author of Saratoga A MESSAGE FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT I am pleased to announce that the draft general management plan/draft environmental impact state ment for Saratoga National Historical Park is now available for your review and comment. The docu ment describes the resource conditions and visitor experience that should exist at Saratoga National Historical Park over the long term. It presents a range of alternatives and assesses the potential envi ronmental and socioeconomic effects of the alternatives on park resources, visitor experience, and surrounding area. As Superintendent, I can assure you that the challenges facing park managers become more complex and varied each year. It is easy to get caught up in these pressing day-to-day issues. That is why the National Park Service seeks to have each park update its plan every 15 or 20 years. It forces us to step back and re-think fundamental questions such as the park's mission and significance, and analyze how to respond to changes facing us. This is not to say we must discard everything that has been done or make changes for change’s sake.