Water Sources & Riparian Enhancement Programmatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

The Historical Range of Beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a Review of the Evidence

Spring 2012 65 California Fish and Game 98(2):65-80; 2012 The historical range of beaver in the Sierra Nevada: a review of the evidence RICHARD B. LANMAN*, HEIDI PERRYMAN, BROCK DOLMAN, AND CHARLES D. JAMES Institute for Historical Ecology, 556 Van Buren Street, Los Altos, CA 94022, USA (RBL) Worth a Dam, 3704 Mt. Diablo Road, Lafayette, CA 94549, USA (HP) OAEC WATER Institute, 15290 Coleman Valley Road, Occidental, CA 95465, USA (BD) Bureau of Indian Affairs, Northwest Region, Branch of Environmental and Cultural Resources Management, Portland, OR 97232, USA (CDJ) *Correspondent: [email protected] The North American beaver (Castor canadensis) has not been considered native to the mid- or high-elevations of the western Sierra Nevada or along its eastern slope, although this mountain range is adjacent to the mammal’s historical range in the Pit, Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and their tributaries. Current California and Nevada beaver management policies appear to rest on assertions that date from the first half of the twentieth century. This review challenges those long-held assumptions. Novel physical evidence of ancient beaver dams in the north central Sierra (James and Lanman 2012) is here supported by a contemporary and expanded re-evaluation of historical records of occurrence by additional reliable observers, as well as new sources of indirect evidence including newspaper accounts, geographical place names, Native American ethnographic information, and assessments of habitat suitability. Understanding that beaver are native to the Sierra Nevada is important to contemporary management of rapidly expanding beaver populations. These populations were established by translocation, and have been shown to have beneficial effects on fish abundance and diversity in the Sierra Nevada, to stabilize stream incision in montane meadows, and to reduce discharge of nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment loads into fragile water bodies such as Lake Tahoe. -

Geologyofeaglelake.Pdf

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES No. 34, 29 pages, 4 figures, 1 plate August 31, k/)j THE GEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF EAGLE LAKE LASSEN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA G. C. GESTER Research Associate (Deceased) Department of Geology California Academy of Sciences Introduction, Previous Work and Acknowledgments The principal objective of this paper is to attempt to portray the geo- logical history of Eagle Lake. My first interest in the geology of Eagle Lake stemmed from an exam- ination of the obsidian deposits in California. The Sixth Annual Report of the State Mineralogist(Hanks, 1886, part I, page 125) states that in Lassen Coun- ty "obsidian is found in great abundance on the east side of Eagle Lake, a mile more or less from Clark's Ranch." No obsidian was found, in place, there. Evidently, however, considerable obsidian was carried there by the Indians and used for making arrowheads, a great many of which have been gathered from the shores of the lake. Another statement that attracted my attention was to the effect that Eagle Lake was classed as a "landslide lake," (Davis, 1933, p. 201; Hinds, 1952, p. 86). "The barrier forming it appears to be a landslide on the south- east side." The examination of the shores of the lake clearly suggested that the lake was barred on its southeastern side by the ancient rocks and flows of basaltic lavas rather than by a landslide. A further search of the literature revealed that there are very few pub- lished data regarding the geology of the lake and the surrounding landscape. -

Management Area 12 - HARVEY

Management Area 12 - HARVEY A. DESCRIPTION Location The Harvey Management Area bor- Management Most of the larger-sized trees in ders the northern edge of the Eagle Lake Dis- the area have been harvested Cattle graze the trict The southern boundary isjust northeast of Harvey Valley, Grays Valley, Upper Pine Creek, and a sliver of the Dixie Valley Range Allot- State Highway 44 The most prominent feature is Harvey Mountain, topped by a Forest Servlce ments Hunting is the primary recreation activ- fire lookout ity The Harvey Valley Demonstration Range contains 127 research plots which are monitored intermittently. The eastern boundary of the Physical Environment Slopes on the 7,354 foot Harvey Mountain are moderate to gentle, Blacks Mountain Expenmental Forest adjoins this area Harvey Valley (5,550 feet) and Grays Valley (5,600 feet) in the southwest are almost flat Precipitation averages 33 inches a year Soils Facilities The Lassen and Nobles Emigrant are moderately deep, and surface rock is common Trails cross the area A cinder pit lies on the on the timbered slopes Grays Valley and Harvey western edge Geothermal lease applications Valley have deep alluvial soils, and Harvey Val- have been filed for lands in the area The area is ley soils are clayey Ephemeral streams drain linked to Highway 44 by a well-developed Forest the mountain slopes into Pine Creek in Harvey road system, and the Union Pacific Railroad Valley parallels Highway 44 Biological Environment Eastside pine and B. STANDARDSAND mixed conifer forests, most of them havlng com- GUIDELINES mercial value, and brushfields cover the slopes Grass-sagebrush and wet meadow communities Recreation occupy the flats Fuel loads in the north half of the area are heavy, due pnmanly to timber 1 Manage the undeveloped camping area at harvest. -

Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway All-American Road

Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway All-American Road Corridor Management Plan Update For Oregon and California December 2018 Cover Photo: View of Lassen Peak and Manzanita Lake in Lassen Volcanic National Park Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park, California Come experience America’s Volcanic Legacy Explore the wonder and beauty of a dramatic volcanic landscape, from Crater Lake in Oregon to Lassen Peak in California. You’ll encounter the ancient natural forces that shaped exquisite mountain lakes and snow-capped peaks all throughout this “volcano to volcano” driving adventure. Along with spectacular scenery, you’ll enjoy legendary history, charming towns, and extraordinary recreational and cultural opportunities. A once-in-a- lifetime experience awaits you along the 500-mile Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway. Ahjumawi Lava Springs i ii Table of Contents Acronym List ......................................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of the Corridor Management Plan (CMP) Update ............................................................... 1 How the Byway Came to Be…A Brief History .......................................................................................... 2 Bringing the Byway Together and Moving Ahead ............................................................................... -

Susan River Watermaster Service Area

SUSAN RIVER WATERMASTER SERVICE AREA ANNUAL USE REPORT - 2017/18 Susan River Watermaster Service Area Annual Use Report – 2017/18 Lassen County, California Decree No.’s 4573, 8174 and 8175 Submitted by December 31, 2018 to The Presiding Judge, Lassen County Superior Court Prepared By: Honey Lake Valley Resource Conservation District 170 Russell Ave. Susanville, CA 96130 This page intentionally left blank Susan River Watermaster Service Area – Annual Use Report 2017/18 Contents General Description: ....................................................................................... 5 Water Supply: ............................................................................................... 6 Methods of Distribution: ................................................................................... 6 Watermaster Activities and Fiscal Information: ....................................................... 7 2017/18 Water Allocation and Distribution: ............................................................ 7 Miscellaneous notable events: ............................................................................ 8 Appendices A-F ............................................................................................ 9 Appendix A: Susan River at Susanville ............................................................... 10 Appendix B: Susan River at the Confluence of Willow Creek..................................... 11 Appendix C: Willow Creek at the Confluence of the Susan River ................................ 12 Appendix D: McCoy -

Draft Northeastern California Plateaus Bioregion Science Synthesis

Public Review Draft 15 Dec 2018. “This information is distributed solely for the purpose of garnering public feedback under applicable information quality guidelines. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy.” Northeastern California Plateaus Bioregion Science Synthesis to Support Forest Plan Development by the Lassen National Forest and the Modoc National Forest Washington, DC: USDA Forest Service. General Technical Report WO-XXX. 1 1 Public Review Draft 15 Dec 2018. “This information is distributed solely for the purpose of garnering public feedback under applicable information quality guidelines. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy.” 2 Authors 3 R. Kasten Dumroese is a research plant physiologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 4 Rocky Mountain Research Station and director, Western Center for Native Plant Conservation and 5 Restoration Science, Moscow, Idaho; David Flores is a research social scientist, Forest Service, Rocky 6 Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, Colorado; Emily R. Haire is a PhD candidate, Department of 7 Sociology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado; Bryce B. Hanberry is a research ecologist, 8 Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Rapid City, South Dakota; W. Keith Moser is a 9 research forester, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Flagstaff, Arizona; Pamela E. 10 Padgett is a research plant physiologist, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Riverside, 11 California; Gregory Russell is a PhD candidate, Department of Journalism and Media Communications, 12 Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado; Leah Stone is a researcher, Department of Journalism 13 and Media Communications, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado; Steven D. -

DIXIE FIRE INCIDENT UPDATE Date: 08/26/2021 Time: 7:00 A.M

DocuSign Envelope ID: 6012FEF5-06A7-4780-9223-2FA34B221696 DIXIE FIRE INCIDENT UPDATE Date: 08/26/2021 Time: 7:00 a.m. @USFSPlumas @USFSPlumas West Zone Information Line: (530) 255-4023 @LassenNF @LassenNF East Zone Information Line: (530) 289-6735 @LassenNPS @LassenNPS Media Line: (530) 588 -0845 ddd @BLMNational @BLMNational Incident Website: www.fire.ca.gov @cal_fire @calfire Email Sign-Up: tinyurl.com/dixiefiresignup INCIDENT FACTS Incident Start Date: 7/13/2021 Incident Start Time: 5:15 p.m. Incident Type: Vegetation Cause: Under Investigation Incident Location: Feather River Canyon near Cresta Powerhouse CAL FIRE Unit: Butte, Lassen-Modoc, Tehama Unified Command Agencies: CAL FIRE, United States Forest Service, National Park Service Size: 747,091 acres Containment: 45% Expected Full Containment: TBD First Responder Fatalities: 0 First Responder Injuries: 3 Civilian Fatalities: 0 Civilian Injuries: 0 Structures Single Residences Destroyed: 682 Single Residences Damaged: 52 Threatened: Multiple Residences Destroyed: 8 Multiple Residences Damaged: 4 11,813 Non-residential Commercial Non-residential Commercial Damaged: Total Destroyed: 139 10 Destroyed: 1,273 Other Minor Structures Other Minor Structures Destroyed: 436 Damaged: 26 Total Mixed Commercial/Residential Mixed Commercial/Residential Damaged: 92 Destroyed: 8 Damaged: 0 CURRENT SITUATION Current Situation Dixie Fire West Zone: Winds calmed after sunset but the fire remained active well into the night. Spotting and torching was limited to areas in and around Lassen Park with fire burning in a number of remote areas with limited access and steep and rugged terrain. Temperatures today are expected to increase with decreasing winds from the north and northwest. Certain evacuation orders have been reduced to warnings and certain warnings have been lifted allowing some residents to return to their homes and businesses. -

Lassen Volcanic National Park California

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE STEPHEN T. MATHER. DIRECTOR RULES AND REGULATIONS LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARK CALIFORNIA LASSEN PEAK IN ERUPTION, MAY 22, 1915 SEASON—JUNE I TO SEPTEMBER 15 U. S. GOVERNMENT PFilNTING OFFICE : 1027 THE NATIONAL PARKS AT A GLANCE [Number, 19; total area, li.SM square miles] Area in National parks in Location square Distinctive characteristics order of creation miles Middle Arkansas IX 46 hot springs possessing curative properties- 1832 Many hotels and boarding houses—19 bath houses under Government supervision. Yellowstone. Northwestern Wyo 3, 318 More geysers than in all rest of world together- 1S72 ming. Boiling springs—Mud volcanoes—Petrified for ests—Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, re markable for gorgeous coloring—Large lakes- Many large streams and waterfalls—Vast wil derness, greatest wild bird and animal preserve in world—Exceptional trout fishing. Sequoia . Middle eastern Cali 604 The Big Tree National Park—Scores of sequoias 1890 fornia. 20 to 30 feet in diameter, thousands over 10 feet in diameter—Towering mountain ranges includ ing Mount Whitney, highest mountain in con tinental United States—Startling precipices— Deep canyons. General Grant.. Middle eastern Cali 4 Created to preserve the celebrated General Grant 1890 fornia. Tree, 35 feet in diameter—31 miles by trail from Sequoia National Park; 85 miles by automobile. Yosemite Middle eastern Cali 1,125 Valley of world-famed beauty—Lofty cliffs—Ro 1890 fornia. mantic vistas—Many waterfalls of extraor dinary height—3 groves of big trees—High Sierra—Waterwheel falls—Good trout fishing. Mount Rainier West central Wash 325 Largest accessible single peak glacier system—28 1899 ington. -

Lassen Volcanic National Par */

LASSEN VOLCANIC NATIONAL PAR */ /, 5*3? Lassen Volcanic Fishing 18 Camping 19 NATIONA L PARK CALIFORNIA Educational Activities 21 Administration 21 Opening and Closing Dates Depend Upon Weather Conditions Park Season 21 How To Reach the Park 21 Contents By Automobile 21 Geologic History 6 By Rail 22 Lassen Peak and Vicinity 6 Bus Transportation 22 Other Dome Volcanoes Near Lassen Peak . 11 Accommodations in the Park 23 Chaos Crags and Chaos Jumbles . 11 Additional Accommodations in and Near Volcanoes of the Central Plateau ... 12 the Park 25 Cinder Cone and the Eastern Range . 14 Interesting Places Near the Park .... 26 Glaciation 14 Points of Interest—Lassen Peak Highway . 27 Other Interesting Features 15 Distances to Principal Places 29 Wildlife 18 References 30 Events OF HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE l820 Arguello exploring party first to tecord and name Lassen Peak 1916 Lassen Volcanic National Park created by act of Congress. (St. Joseph's Mountain). ast 1921 Lassen Peak ceased to erupt and subsided into a state of quiescence. j 8 CO—CI L lava flow from the Cinder Cone. Witnessed by travelers along the Noble Trail. Portions of this trail lie within the park boundaries. I925 Active development of park began. Lassen Peak Highway started. 1864 Helen Brodt, first white woman to climb Lassen Peak; made the ascent 1931 Lassen Peak Highway completed. Three-day dedication celebration with Major Reading. Lake Helen named after Helen Brodt. held in park. 1906 Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone National Monuments set aside May 6 by President Theodore Roosevelt. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE 1914 May 30. -

TRADE and TRAILS in ABORIGINAL CALIFORNIA by L

Reports of the U9NIVERSITY OF&ALIFORNIA LLARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 8 L.fr TRADE AND TRAILS IN ABORIGINAL CALIFORNIA By L. L. Sample Issued September 15, 1950 The University of California ArchaeologIcal Survey Department of Anthropology University of California Berkeley 4. California TORADE AND T2AILS IN ADORIGE7TAL CALIFOP111IA CO;TqNTTS Page Introduction . ...*s ,* ... IsI., . e . 1 Trading customs ..... ... * ., 3 Articles traded a . , .. 7 Bibliographic references to trails shovin on map .....X * . 24 Bibliography . e * e e * * * * * 2 ILLIJST'AT IONS Indian trails and trade routes in California . after page 23 x. if *0 R it. *ti M' DITLRO,0DUCTION This preliminary report does not cover fully the data on Indian trade in California, It may show, however, that the study of native trade is an important approach to the study of aboriginal culture contact in Californi.a. The trails are lines of direct diffusion and culture may spread rapidly along these routes. Charting of material traded betworeen particular tribes as obtained from etihnograohic and historical sources may help the archaeologist analyze sources of artifact materials found in sites. Trade as described in this paper represents the situation as it existed at the time of Caucasian discovery and during the early period of contact. This means a different time period for northern, central-, southern, and sierral California, each explored at different times. Some of -,;he trade mentioned is undoubtedly very old. It is possible, also, that some was stimulated by the presence of white traders and highly valued white mants goods. Wherever the circmastances point to its being a late development, these facts are pointed out. -

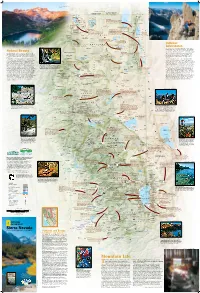

Sierra Nevada’S Endless Landforms Are Playgrounds for to Admire the Clear Fragile Shards

SIERRA BUTTES AND LOWER SARDINE LAKE RICH REID Longitude West 121° of Greenwich FREMONT-WINEMA OREGON NATIONAL FOREST S JOSH MILLER PHOTOGRAPHY E E Renner Lake 42° Hatfield 42° Kalina 139 Mt. Bidwell N K WWII VALOR Los 8290 ft IN THE PACIFIC ETulelake K t 2527 m Carr Butte 5482 ft . N.M. N. r B E E 1671 m F i Dalton C d Tuber k Goose Obsidian Mines w . w Cow Head o I CLIMBING THE NORTHEAST RIDGE OF BEAR CREEK SPIRE E Will Visit any of four obsidian mines—Pink Lady, Lassen e Tule Homestead E l Lake Stronghold l Creek Rainbow, Obsidian Needles, and Middle Fork Lake Lake TULE LAKE C ENewell Clear Lake Davis Creek—and take in the startling colors and r shapes of this dense, glass-like lava rock. With the . NATIONAL WILDLIFE ECopic Reservoir L proper permit you can even excavate some yourself. a A EM CLEAR LAKE s EFort Bidwell REFUGE E IG s Liskey R NATIONAL WILDLIFE e A n N Y T REFUGE C A E T r W MODOC R K . Y A B Kandra I Blue Mt. 5750 ft L B T Y S 1753 m Emigrant Trails Scenic Byway R NATIONAL o S T C l LAVA E Lava ows, canyons, farmland, and N E e Y Cornell U N s A vestiges of routes trod by early O FOREST BEDS I W C C C Y S B settlers and gold miners. 5582 ft r B K WILDERNESS Y . C C W 1701 m Surprise Valley Hot Springs I Double Head Mt.