The Long Road to Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boletín Oficial Del Estado

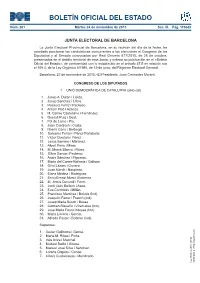

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL ESTADO Núm. 281 Martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 Sec. III. Pág. 110643 JUNTA ELECTORAL DE BARCELONA La Junta Electoral Provincial de Barcelona, en su reunión del día de la fecha, ha acordado proclamar las candidaturas concurrentes a las elecciones al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado convocadas por Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, presentadas en el ámbito territorial de esta Junta, y ordena su publicación en el «Boletín Oficial del Estado», de conformidad con lo establecido en el artículo 47.5 en relación con el 169.4, de la Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General. Barcelona, 23 de noviembre de 2015.–El Presidente, Joan Cremades Morant. CONGRESO DE LOS DIPUTADOS 1. UNIÓ DEMOCRÀTICA DE CATALUNYA (unio.cat) 1. Josep A. Duran i Lleida. 2. Josep Sanchez i Llibre. 3. Rosaura Ferriz i Pacheco. 4. Antoni Picó i Azanza. 5. M. Carme Castellano i Fernández. 6. Queralt Puig i Gual. 7. Pol de Lamo i Pla. 8. Joan Contijoch i Costa. 9. Noemi Cano i Berbegal. 10. Salvador Ferran i Pérez-Portabella. 11. Víctor Gonzalo i Pérez. 12. Jesús Serrano i Martínez. 13. Albert Peris i Miras. 14. M. Mercè Blanco i Ribas. 15. Sílvia Garcia i Pacheco. 16. Anaïs Sánchez i Figueras. 17. Maria del Carme Ballesta i Galiana. 18. Oriol Lázaro i Llovera. 19. Joan March i Naspleda. 20. Elena Medina i Rodríguez. 21. Enric-Ernest Munt i Gutierrez. 22. M. Jesús Cucurull i Farré. 23. Jordi Lluís Bailach i Aspa. 24. Eva Cordobés i Millán. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Disproportional Complex States: Scotland and England in the United Kingdom and Slovenia and Serbia Within Yugoslavia

IJournals: International Journal of Social Relevance & Concern ISSN-2347-9698 Volume 6 Issue 5 May 2018 Disproportional Complex States: Scotland and England in the United Kingdom and Slovenia and Serbia within Yugoslavia Author: Neven Andjelic Affiliation: Regent's University London E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides comparative study in the field of nationalism, political representation and identity politics. It provides comparative analysis of two cases; one in the This paper is reflecting academic curiosity and research United Kingdom during early 21st century and the other in into the field of nationalism, comparative politics, divided Yugoslavia during late 1980s and early 1990s. The paper societies and European integrations in contemporary looks into issues of Scottish nationalism and the Scottish Europe. Referendums in Scotland in 2014 and in National Party in relation to an English Tory government Catalonia in 2017 show that the idea of nation state is in London and the Tory concept of "One Nation". The very strong in Europe despite the unprecedented processes other case study is concerned with the situation in the of integration that undermined traditional understandings former Yugoslavia where Slovenian separatism and their of nation-state, sovereignty and independence. These reformed communists took stand against tendencies examples provide case-studies for study of nation, coming from Serbia to dominate other members of the nationalism and liberal democracy. Exercise of popular federation. The role of state is studied in relation to political will in Scotland invited no violent reactions and federal system and devolved unitary state. There is also proved the case for liberal democracies to solve its issues insight into communist political system and liberal without violence. -

Scottish Nationalism in the Weekly Magazine

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 16 | Issue 1 Article 3 1981 Scottish Nationalism in The eekW ly Magazine Ian C. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Ian C. (1981) "Scottish Nationalism in The eW ekly Magazine," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 16: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol16/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ian C. Walker Scottish Nationalism in The Weekly Magazine The standpoint on nationalistic problems adopted by writers in the Edinburgh Weekly Magazine! provides an excellent illus tration of the peculiarly contradictory sentiments about their country common among Scotsmen of the eighteenth century. On the one hand they were ashamed of their dialect speech; on the other they flew to the defence of their national identity when it was attacked by people like Johnson2 and Wilkes. This phe nomenon has already been commented on by others,3 and it falls within the present article merely to continue the description of the subject so far as it figures in the pages of the Weekly Magc'.zine. The problem of language may be considered first. Under this general term three separate factors must be distinguished, al though they might often occur in conjunction: mispronuncia tion of English words, misuse of English words, and the use of purely dialect expressions. -

Europa L’Entrevista Ja Som a L’Estiu I Moltes De De La Nostra Voluntat

La Veu Butlletí de Reagrupament Independentista Europa L’entrevista Ja som a l’estiu i moltes de de la nostra voluntat. Europa les esperances de la primavera ens espera com un estat més i Dr. Moisès Broggi: ja no les tenim... només depèn de nosaltres de Una esperança: que el voler-ne ser protagonistes. “Cada vegada hi ha Parlament Europeu fos El company Jordi Gomis ho menys arguments competent per regular el tenia molt clar, i com ell va dret de ciutadania de la UE; deixar escrit: «És una obvietat per continuar sent una altra: que la situació que si Catalunya fos un Estat, part d’un estat que econòmica no ens endinsés no tindríem espoli fiscal, i en un pou de la mà de la per tant, els recursos dels que ens ofega” incompetència espanyola. disposem es multiplicarien PÀGINA 4 La Comissió Europea ens automàticament. Més enllà de ha dit que el Parlament no desempallegar-nos d’un Estat és competent per regular que xucla els nostres recursos Recordem Jordi Gomis sobre la ciutadania europea, i ens ofega econòmicament, Un altre Franco però ens ha indicat dos fets les dades també demostren molt importants: admet la que els estats petits de la UE Dèficits i balances possibilitat de secessió d’una han crescut molt per sobre fiscals part d’un Estat membre i que els grans, prenent les considera la solució en la dades que van des del 1979 /&(- negociació dins l’ordenament fins els nostres dies... En jurídic internacional. definitiva, tenim dues opcions: D’aquesta forma la Comissió esperar que després de 23 Resultats de 30 anys Europea desmenteix les anys -

Cal Seguir Endavant

Sumari La Veu Internacional Butlletí de Reagrupament Independentista Afers exteriors: el Diplocat per Josep Sort Cal seguir endavant PÀGINA 2 Municipalisme Segons l’acord de legislatura polítics de Catalunya ens pot Homilies contra entre CIU i ERC, el dia 30 de abocar a una gran decepció Lapao juny d’enguany caldria haver ciutadana. El President demanat l’autorització al Mas va entrar a la ratera el per Carles Bonaventura govern espanyol per a dur a 25N i, cada dia que passa, PÀGINA 3 terme la “consulta”. Qualsevol està més atrapat en la seva persona amb un sentit mínim solitud. El cap de l’oposició/ Cultura de la lògica interpreta que soci de govern està encantat això vol dir haver aprovat veient com es dessagna el Qui decideix? una pregunta clara i una govern, amb la pretensió per Montserrat Tudela data. És una obvietat que a única i exclusiva de fer el mig mes de juny no hi ha sorpasso i, es suposa, liderar PÀGINA 4 aprovada ni una pregunta una comunitat autònoma ni una data. Sembla que el arruïnada i exhausta. Cal Territorials President de la Generalitat una feina conjunta dels dóna per fet el tràmit de partits que volen la llibertat Encara cal picar petició al govern espanyol del poble de Catalunya molta pedra d’autorització de la realització i deixar per a d’altres per Xavier Todó del procés de consultar al temps els seus interessos poble de Catalunya quina és partidistes. Cal unitat d’acció PÀGINA 5 la seva voluntat de futur. És, i generositat. Vull recordar, amb perdó, President, una un cop més, que cap govern La ploma convidada broma de molt mal gust. -

'S Elsass, Unser Land!*

Élections départementales Canton de Saverne Collectivité européenne d’Alsace – 2021 ’s Elsass, * Lena unser Land! DECKER Pour notre pays, notre terre et nos libertés ! 26 ans, agent administratif à Saverne. *L’Alsace, notre terre ! Engagée dans plusieurs associations, la défense de notre patrimoine culturel, linguistique et naturel lui tient à cœur. Dialectophone, elle souhaite que notre langue ne Stop Grand Est, en avant l’Alsace ! devienne pas un objet de musée, mais au contraire que les générations suivantes continueront de parler alsacien. En 2015, François Hollande a décidé de supprimer la région Alsace. Alors qu’une grande partie de la classe politique locale a finalement accepté cette réforme à la fois incohérente et Remplaçante : anti-démocratique, des dizaines de milliers de citoyens se sont mobilisés aux côtés d’Unser MARIE-FRANÇOISE SCHNEIDER Land afin que l’Alsace ne disparaisse pas. En janvier dernier, les départements du Haut-Rhin 74 ans. et du Bas-Rhin ont été réunis dans une nouvelle entité dénommée « Collectivité européenne Alsacienne d’adoption, elle a vécu dans différentes villes d’Alsace » (CEA). C’est une première victoire, mais ne soyons pas dupes : la CEA n’est rien en France, en Suisse et en Afrique, d’autre qu’un simple département aux compétences limitées. D’autre part, l’Alsace est tou- avant de s’établir à Saverne. Elle a travaillé sur les sujets de jours noyée dans le Grand Est. Tout reste à faire ! migration et d’intégration. Alors que les Français sont favorables au maintien des cultures minoritaires Prenons notre destin en main dans d’autres parties du monde, nos gouvernants font Justice sociale, politique de santé, maintien de l’emploi, sécurité, démocratie participative, tout pour en finir avec les cultures minoritaires de préservation de l’environnement, maîtrise de la mondialisation : il faut agir… mais encore France, notamment en Alsace : c’est ce qui a motivé Marie-Françoise à s’engager pour Unser Land. -

Manifest Sobre El Reagrupament Familiar

MANIFEST Davant les reiterades notícies i declaracions respecte a possibles modificacions de la Llei sobre drets i llibertats dels estrangers a Espanya i la seva integració social i el Reglament que la desenvolupa, pel que fa a les condicions pel Reagrupament Familiar, la Comissió Permanent del Consell Municipal d’Immigració de Barcelona, vol manifestar: 1. El dret al reagrupament familiar està recollit en l’ordenament jurídic de la Unió Europea Aquest dret està emparat en la directiva 2003/86/CE del Consell del Unió Europea de 22 de setembre de 2003 sobre el dret al reagrupament familiar. Així mateix el dret a la família esta reconegut en el nostre ordenament jurídic, pels articles 18 i 32 de la Constitució Espanyola, per l’article 16 de la Llei sobre drets i llibertats dels estrangers a Espanya i la seva integració social; També és un dret reconegut per la Carta dels Drets Humans i per la Convenció de Roma. 2. La possibilitat de restringir el reagrupament dels ascendents de les persones immigrades és una mesura que no afavorirà l’arrelament i la cohesió social i que, per altra banda, tindrà poca incidència real en el conjunt de la població. El reagrupament familiar d’ascendents ve a fer una funció necessària per la cohesió social, ajuda a l’arrelament i permet consolidar els nuclis familiars. Actualment el reagrupament d’ascendents ja és molt minoritari – al voltant del 9% del total de sol·licituds – a més a la ciutat de Barcelona afecta especialment a persones de nacionalitat espanyola. Els actuals requisits ja limiten el reagrupament d’ascendents a persones, en general, de més de 65 anys sempre i quan es demostri que l’ascendent reagrupat té una dependència econòmica absoluta respecte al reagrupant. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

2016 Country Review

Spain 2016 Country Review http://www.countrywatch.com Table of Contents Chapter 1 1 Country Overview 1 Country Overview 2 Key Data 4 Spain 5 Europe 6 Chapter 2 8 Political Overview 8 History 9 Political Conditions 12 Political Risk Index 63 Political Stability 77 Freedom Rankings 92 Human Rights 104 Government Functions 107 Government Structure 110 Principal Government Officials 121 Leader Biography 128 Leader Biography 128 Foreign Relations 130 National Security 144 Defense Forces 146 Appendix: The Basques 147 Appendix: Spanish Territories and Jurisdiction 161 Chapter 3 163 Economic Overview 163 Economic Overview 164 Nominal GDP and Components 190 Population and GDP Per Capita 192 Real GDP and Inflation 193 Government Spending and Taxation 194 Money Supply, Interest Rates and Unemployment 195 Foreign Trade and the Exchange Rate 196 Data in US Dollars 197 Energy Consumption and Production Standard Units 198 Energy Consumption and Production QUADS 200 World Energy Price Summary 201 CO2 Emissions 202 Agriculture Consumption and Production 203 World Agriculture Pricing Summary 206 Metals Consumption and Production 207 World Metals Pricing Summary 210 Economic Performance Index 211 Chapter 4 223 Investment Overview 223 Foreign Investment Climate 224 Foreign Investment Index 226 Corruption Perceptions Index 239 Competitiveness Ranking 251 Taxation 259 Stock Market 261 Partner Links 261 Chapter 5 263 Social Overview 263 People 264 Human Development Index 267 Life Satisfaction Index 270 Happy Planet Index 281 Status of Women 291 Global Gender -

Inside Spain Nr 124 16 December 2015 - 20 January 2016

Inside Spain Nr 124 16 December 2015 - 20 January 2016 William Chislett Summary Fresh election on the cards as parties fail to bury differences and form new government. Catalan acting Prime Minister Artur Mas quits to avert new elections. King Felipe’s sister the Infanta Cristina on trial for tax fraud. Registered jobless drops to lowest level since 2010. Santander acquires Portugal’s Banco Banif. Domestic Scene Fresh election on the cards as parties fail to bury differences and form new government… One month after an inconclusive election, parties struggled to form a new government, raising the prospect of a fresh election. The anti-austerity Podemos and the centrist Ciudadanos broke the hegemony of the conservative Popular Party (PP) and the centre-left Socialists (PSOE), the two parties that have alternated in power since 1982, but the results of the election on 20 December created a very fragmented parliament with few coherent options to form a government. The PP of Mariano Rajoy won 123 of the 350 seats in parliament on close to 30% of the vote, way down on the absolute majority of 186 it obtained in the 2011 election and its lowest number (107) since 1989 (see Figure 1). The Socialists captured 90 seats, their worst performance since 1988 (118). Podemos captured 69 seats (27 of them won by its affiliated offshoots in Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia which went under different names) and Ciudadanos 40. 1 Inside Spain Nr 124 16 December 2015 - 16 January 2016 Figure 1. Results of general elections, 2015 and 2011 (seats, millions of -

Isla De Man 1

Isla de Man 1. PERFIL FISICO Características físicas de la localidad El terreno de la isla es variado. Hay áreas montañosas en el norte y en el sur, dividas por un valle central, que corre entre las ciudades de Douglas y Peel. El extremo norte es excepcionalmente plano, consistiendo principalmente en depósitos aumentados por la deposición de avances glaciales. Hay playas de grava, depositadas más recientemente, en la Punta de Ayre. El punto más alto de la isla es el monte Snaefell, que alcanza 621 msnm de altura en su punto más alto. Mapa de la localidad La isla de Man es una isla en el noroeste del continente Europeo, situada en el mar de Irlanda, entre las islas de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda. Extensión territorial La isla mide aproximadamente 22 km de ancho y 52 km de largo, con un área total de 572 km².17 Sus coordenadas geográficas corresponden a 54°15′N 4°30′O. La isla de Man posee un total de 160 km de costa, sin tener ningún cuerpo de agua de tamaño significativo dentro de la misma. La isla reclama 12 M de mar patrimonial, pero solo tiene derechos exclusivos de pesca en las primeras 3 M. En torno a ella se ubican algunas islas pequeñas como Calf of Man, St Patrick y St Michael. 2. GOBERNANZA LOCAL Población Según el censo intermedio de 2011 la isla de Man tiene 84.497 habitantes, de los cuales 27.935 residen en la capital de la isla, Douglas. La mayoría de la población es originaria de las Islas Británicas, con el 47,6% de la población nacida en la isla de Man, el 37.2% en Inglaterra, 3,4% en Escocia, 2,1% en Irlanda del Norte, 2,1% en la República de Irlanda, 1,2% en Gales y 0,3% en las Islas del Canal.