Source Water Master Plan Volume 2 – Detailed Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2014-2015 PDF Version

imagesBOULDER COUNTY PARKS AND OPEN SPACE news properties nature history events winter 2014-15 Images Artist-in-Residence at volume 36, number 4 Th e mission of the Boulder County Parks Caribou Ranch and Open Space Department is to conserve natural, cultural and agricultural resources and provide public uses that refl ect sound Caribou Ranch was, at one time, home to an artistic endeavor: the Caribou Ranch resource management and community values. recording studio. Th is studio once hosted hundreds of musicians in the 70s and 80s COVER ART: Walker Ranch Homestead, before a fi re damaged the structure in 1985. Michael Jackson, Carol King, Elton John, photo by Barry Shook U2 and the Beach Boys are just some of the artists who drew inspiration from living PHOTOGRAPHS & ILLUSTRATIONS and recording in the mountains in Boulder County. With a similar concept in mind, the Volunteer . Artist-in-Residence (AiR) Program of Caribou Ranch is now a way for artists of many Elizabeth Etzel and Fletcher Jacobs genres to fi nd inspiration in Boulder County’s natural beauty. South Boulder Creek . Kristen Turner Elk Herd . .Cathy Bryarly Th e AiR Program gives county residents a tangible connection to today’s artists— Level 3 Partners . .Craig Sommers not only musicians, but painters, illustrators, photographers, visual/fi lm artists, sculp- Frosty Spiderweb . Elizabeth Etzel tors, performers, poets, writers, composers Owl . .Janis Whisman and craft s/artisans, too. Junior Rangers . Graham Fowler Th e program also gives artists an NATURE DETECTIVES opportunity to experience open space in a Katherine Young and Deborah Price setting tailored to the artist’s needs. -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

Backstage Auctions, Inc. the Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog

Backstage Auctions, Inc. The Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog Lot # Lot Title Opening $ Artist 1 Artist 2 Type of Collectible 1001 Aerosmith 1989 'Pump' Album Sleeve Proof Signed to Manager Tim Collins $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1002 Aerosmith MTV Video Music Awards Band Signed Framed Color Photo $175.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1003 Aerosmith Brad Whitford Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1004 Aerosmith Joey Kramer Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1005 Aerosmith 1993 'Living' MTV Video Music Award Moonman Award Presented to Tim Collins $4,500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1006 Aerosmith 1993 'Get A Grip' CRIA Diamond Award Issued to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1007 Aerosmith 1990 'Janie's Got A Gun' Framed Grammy Award Confirmation Presented to Collins Management $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1008 Aerosmith 1993 'Livin' On The Edge' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1009 Aerosmith 1994 'Crazy' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1010 Aerosmith -

Pacific Ocean Blue Bambu

Dennis Wilson - Pacific Ocean Blue Produced by Dennis Wilson & Gregg Jakobson Released August 22, 1977 - Caribou PZ 34354 (CBS) Pacific Ocean Blue - Legacy Edition Originial Recordings Produced by Dennis Wilson & Gregg Jakobson Bonus Tracks Produced by Dennis Wilson, John Hanlon & Gregg Jakobson Executive Producer: James William Guercio Released June 17, 2008 - Caribou/Epic/Legacy 88697-07916-2 (Sony/BMG) Disc One Dennis Wilson had always been considered the quintessential "Beach Boy": not in a musical sense (that, of course, was Brian), but in a lifestyle sense. His love of surfing inspired the others to adopt the image that launched the band, and his further adventures in the worlds of fast cars, fast bikes, and fast women continued to fuel the imagination and song catalog of his older brother and cousin. But in the first five or six years of their career, his musical contributions were limited to drumming and singing backup (and sometimes not even that), with an occasional lead vocal opportunity (either covers of other artists or new songs that Brian and Mike would throw his way). However, with Brian Wilson's retreat from full artistic control of the band in 1967, the other members (Dennis included) began to be relied upon more and more for compositional and production efforts. Dennis' first contributions in this respect appear on the 1968 Friends album, and would continue over the next five years; tunes like "Little Bird", "Be With Me", "Celebrate The News", and "Forever" were highlights of the late '60s-early '70s Beach Boys era. In order for Dennis to evolve musically into something more than "just the fun-loving playboy drummer", he needed to master a melodic/chordal instrument well enough to compose on it. -

1 PHILIP LOBEL. Born 1956. TRANSCRIPT of OH 2055V This

PHILIP LOBEL. Born 1956. TRANSCRIPT of OH 2055V This interview was recorded on September 20, 2015, for the Maria Rogers Oral History Program. The interviewer and videographer is Sue Boorman. The interview was transcribed by Susan Becker. ABSTRACT: This interview is part of a series about three football games known as the Hairy Bacon Bowl, which occurred during the early 1970s. Participants included University of Colorado students who identified with hippie culture and/or anti-war sentiment, versus campus and Boulder police officers. The games were seen as a way to address tensions between the two groups. The idea for the games originated with the Program Council office at CU. Phil Lobel became involved with Program Council in 1973 and then led the program from 1976 to 1979. He touches on the concept of the Hairy Bacon Bowl, but by the time he was Program Council director, the days of the Hairy Bacon Bowl competitions were almost over—he describes the change in culture at that time from the tense, seriousness of anti-war protests to a light-hearted one exemplified by the practice of streaking. Much of the interview focuses on the transformation of Program Council into one of the most successful student organizations of its kind in the country (culminating in Program Council winning the 1978 Billboard Magazine College Talent Buyer of the Year Award) and how Mr. Lobel’s work for Program Council paved the way to his long career in entertainment public relations. He provides a fascinating window into the workings of Program Council and into the music scene of the 1970s. -

Caribou Ranch Open Space Management Plan

CARIBOU RANCH OPEN SPACE MANAGEMENT PLAN Boulder County Parks and Open Space Department Approved by the Board of County Commissioners October 15, 2002 Caribou Ranch Management Plan Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... iv SUMMARY OF RESOURCE EVALUATION..............................................................................1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................1 1.1 General Description of Property .................................................................1 1.2 Physical Characteristics and Landscape Setting .........................................1 2.0 VEGETATION RESOURCES ...............................................................................4 2.1 General Description ....................................................................................4 2.2 Significant Resources ..................................................................................5 3.0 WILDLIFE RESOURCES ......................................................................................7 3.1 General Description ....................................................................................7 3.2 Significant Resources ..................................................................................8 -

The Ben Gray Lumpkin Collection of Colorado Folklore

Gene A. Culwell The Ben Gray Lumpkin Collection of Colorado Folklore Professor Ben Gray Lumpkin, who retired from the University of Colorado in June of 1969, spent more than twenty years of his academic career amassing a large collection of folksongs in the state of Colorado. At my request, Profes- sor Lumpkin provided the following information concerning his life and career: Son of John Moorman and Harriet Gray Lumpkin, I was born De- cember 25, 1901, in Marshall County, Mississippi, on a farm about seven miles north of Holly Springs. Grandpa was a Methodist cir- cuit rider, but had to farm to eke out a living because his hill-coun- try churches were too poor to support his family. Because we lived too far from the Hudsonville school for me to walk, I began schooling under my mother until I was old enough to ride a gentle mare and take care of her at school—at the age of 8. When my father bought a farm in Lowndes County, Mississippi, my brother Joe and sister Martha and I went to Penn Station and Crawford elementary schools. Having finished what was called the ninth grade, I went to live with my Aunt Olena Ford, and fin- ished Tupelo High School in 1921, then BA, University of Missis- sippi, 1925. I worked as the secretary and clerk in the Mississippi State Department of Archives and History (September 1925 to March 1929) and in the Mississippi Division office of Southern Bell Telephone Company (March 1929 to August 1930). I taught English and other subjects in Vina, Alabama, High School (August 1930 through January 1932). -

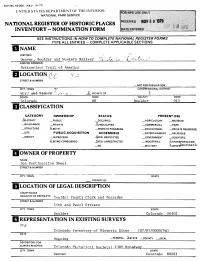

Nomination Form

FormNo. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS _________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_____ I NAME HISTORIC Denver, Boulder and Western Railway /t-'••••*£&••'• ^*. A_,^c:V\,«..^: •_________ AND/OR COMMON Switzerland Trail of America LOCATION CO 7 STREET & NUMBER —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Ward "aftd—&ido •ra""y ^/UA.-C s -&- VICINITY OF 2 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Colorado 08 Boulder 013 HfCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE Jk)ISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING<S) —PRIVATE -AjNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE X.BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC X.BEING CONSIDERED _XYES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL ^.TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY ^.OTHER?-601^ 63 *-^ [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME See Continuation Sheet STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE __ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. County Clerk and Recorder STREET & NUMBER and Pearl Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Boulder Colorado 80302 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Colorado Inventory of Historic Sites (07/03/0000/06) DATE Ongoing -FEDERAL JLSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Colorado Historical Society: 1300 Broadway CITY. TOWN STATE Denver Colorado 80203 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE J^GOOD —RUINS JJALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Located in the western section of Boulder County, Colorado, the Switzerland Trail is a narrow, serpentine historic district that was once the right-of-way of the Denver, Boulder and Western Railway, which served the small mining communities in the region. -

February 1985

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 9, NO. 2 Cover Photo by Rick Mattingly FEATURES MEL LEWIS It was 19 years ago this month that the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra started playing Monday nights at New York's Village Vanguard, and the band—now led solely by Lewis—is still there. Mel has had a lot of time to observe what is going on in jazz and jazz education, and here he shares his thoughts on those subjects, as well as his feelings about the importance of knowing the traditions of the instrument. by Rick Mattingly 8 MARK BRZEZICKI Although this is the age of electronics, Mark Brzezicki, drummer with Big Country, feels that it is important to have a real drummer and a real drum sound in today's music. In this exclusive interview, he reveals the means by which he ensures the prominence of the drum part in Big Country's music, and describes his approach to recording when working with artists such as Pete Townshend, Frida, Photo by Rick Mattingly and Roger Daltrey. 14 by Stanley Hall MICK AVORY When the Kinks emerged in the mid '60s as part of the "British Invasion," few people would have thought that any of those bands would still be around 20 years later. But the Kinks—with most of the original members, including drummer Mick Avory—are still going strong. Avory discusses his drumming style as he looks back at his years with the group. by Robert Santelli 18 INSIDE MEINL by Donald Quade 22 NIGEL OLSSON Heart by Robyn Flans 26 Photo by Ebet Roberts COLUMNS EDUCATION THE JOBBING DRUMMER EQUIPMENT The Show Must Go On 98 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP FROM THE PAST by Simon Goodwin Swing Drummers In The Movies Losing Your Grip THE MUSICAL DRUMMER by James E. -

S Print This Document Martin Used the Console to Produce Albums For

Vintage King Restores Caribou Ranch Neve 8016 Seite 1 vonZ S Print this document Detroit, MI (June 3, 2009)--Vintage King Audio recently completed a full restoration on the Neve 8016 console that was once part of the legendary Caribou Ranch recording studio. After a four- month refirbishment, the console was sold and delivered to Prime Studio in Austria for its control room B, an all-analog suite that officially opened June 1. The console's installation at Prime Studio marks its return to Europe after over three decades in the states, where it was part of music history on albums for Earth Wind & Fire, Chicago, Elton John, Billy Joel, America, Stephen Stills and others. The Neve 8016's legacy began in1972, in London, where it was built. Original owner Sir George Martin used the console to produce albums for America and others before selling it to Caribou Ranch founder, James Guercio. Legendary in both setting and sound, Caribou was a destination for major artists like Chicago, who recorded five studio albums on the Neve 8016; Elton John, for his album Caribou (named after the studio); and Earth Wind & Fire, who recorded two albums at the ranch, including the Grammy-winning That's the Way af the World. After an electrical fire in 1985, the studio's doors were closed and much of the salvaged equipment was put into storage. Guercio ultimately donated the Neve 8016 to the University of Colorado at Denver, its last stop before Vintage King acquired the console earlier this year and began restoration for Prime Studio. -

Distinctive Homes of the Boulder Valley

DISTINCTIVE HOMES OF THE BOULDER VALLEY WHAT YOU GET FOR $4 MILLION Minimalist mountain Storied Caribou Ranch masterpiece on the sale block PAGE 10 PAGE 3 MAY 2014 | BIZWEST | THE BUSINESS JOURNAL OF THE BOULDER VALLEY AND NORTHERN COLORADO 2 VIEW ALL OUR LISTINGS: EveryEvery HomeHome IsIs aa LLandmarKandmarK ...... WWW.COLORADOLANDMARK.COM ICONIC BLUE MOUNTAIN ESTATE ONE OF COLORADO’S MOST IMPORTANT PIECES OF ARCHITECTURE 8775 BLUE MOUNTAIN DR., GOLDEN $6,950,000 165 GREEN ROCK DR., BOULDER $3,950,000 e ultimate in privacy, views, quality & comfort, Joel Ripmaster 303-641-3377 is property could never be replicated, in part due to Emily Gadacz 303-868-1010 towering over the Colorado Front Range from a subtle, its brilliant integration into the surrounding landscape yet convenient location on 25+ private acres. e present owner built this as an everlasting estate (Gyp Rock), its serene location, yet walking distance to Pearl Street Mall. Charles Haertling with the nest materials imaginable. Truly a piece of art: this home inspires you in every way! masterfully designed the home into a massive rock, lending as its backdrop. Truly nothing like 5BD/6BA/10,397 SQFT. this in the Front Range. 4BD/5BA/5,780 SQFT. MAGNIFICENT FLAGSTAFF LOT NEW MAPLETON HILL LISTING! 785 FLAGSTAFF ROAD, BOULDER $3,250,000 511 HIGHLAND AVENUE, BOULDER $1,525,000 Two magnicent acres nestled on sunny hillside of Joel Ripmaster 303-641-3377 Gorgeous Highland Ave! Lush gardens with many areas Michelle Clifford 303-579-1029 Flagsta Mountain. Built in 1951, this property is for outdoor enjoyment. Additions include master suite “Grandfathered”. -

January 2015 —Mountain States Collector South Broadway

J anuary 2015 JANUARY 2010 E STaBliShEd in 1972 +(1)#1)V(%,&olum e,& 43, numb e#. r) 1 ESTABLISHED IN 1972 Volume 38, Number 1 DEVOTED TO ANTIQUES, COLLECTIBLES, FURNITURE, ART AND DESIGN. '(*)$#%'Homestead Antiques +/0!.",#.+((#!0+./405/%+2&)# Celebrates Two Years The Story Behind the Cards Page 11 !)+.0+'*+)++"&.0)#*0++&#&!By Dede Horan +"#&+) &-)'*+)()"'. Anyone who collects vintage postcards has probably come across ones of illustrated highway maps. If these maps were from the M5#.9#;56*'4'9+..$'*70&4'&51($1:'51(2156%#4&5#59'..#5idwest with detailed small illustrations, they may well have #.#4)'#55146/'061(16*'4'2*'/'4#+0%.7&+0)64#&'%#4&5'#4.;2*1been designed by Gene McConnell, an artist and photographer 6f1)4#2*5#&8'46+5+0)%#.'0-/'0755*''6/75+%'6%!*'4'+551/'rom North Platte, Nebraska. 6*+0)(14'8'4;10'#66*'5*19H e receiv ed his art training at the Denver Art Institute which he a1(6*'&'#.'45*#8'#&&'&(4'5*0'9+08'0614;616*'+4561%-ttended on the GI Bill. His first job was as commercial tech - n0#44#;1($#4)#+0$1:'5#0&#((14&#$.'+6'/5#4'+&'#.(146*'$')+0ica l illustrator at Fort W arren. Later when he returned to North 0P+0)%1..'%614'574'61#5-#$1766*'>(4''?2156%#4&5(14%*+.&4'0latte he worked for the lo cal newspaper creating logos and il - #)'5 #0&70&'46?5#)4'#69#;61)'66*'/+06'4'56'&+02156%#4&5lustrations for advert isements. (;17#4'+06190(146*'561%-5*195612$;#0&$4195'6*'9'56'40In the early 195 0s McCon nell be gan pro duci ng humor post - /'/14#$+.+#car ds for the D un lap Comp an y.