Making the Trombone Cool for 54 Years an Interview with James Pankow CONTENTS 23 46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 Conference or Workshop Item How to cite: Smith, David and Blundel, Richard (2016). Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75. In: Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG) Joint Conference, 27-29 May 2016, Humbolt University, Berlin. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2016 The Authors https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://ebha.org/public/C6:pdf Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Joint Conference Association of Business Historians (ABH) and Gesellschaft für Unternehmensgeschichte (GUG), 27-28 May 2016, Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Disruptive Innovation in the Creative Industries: The adoption of the German horn in Britain 1935-75 David Smith* and Richard Blundel** *Nottingham Trent University, UK and **The Open University, UK Abstract This paper examines the interplay between innovation and entrepreneurial processes amongst competing firms in the creative industries. It does so through a case study of the introduction and diffusion into Britain of a brass musical instrument, the wide bore German horn, over a period of some 40 years in the middle of the twentieth century. -

Intermezzo May/June 2021

Virtual Membership Meeting: Virtual Membership Meeting: May/June 2021 Monday, May 10th, 2021 Monday, June 14th, 2021 Vol. 81 No. 3 @ 6:00 pm @ 6:00 pm Musician Profile: Chicago’s Jimmy Pankow and Lee Loughnane Page 6 Looking Back Page 11 The Passing of Dorothy Katz Page 28 Local 10-208 of AFM CHICAGO FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFICERS – DELEGATES 2020-2022 Terryl Jares President Leo Murphy Vice-President B.J. Levy Secretary-Treasurer BOARD OF DIRECTORS FROM THE PRESIDENT Robert Bauchens Nick Moran Rich Daniels Charles Schuchat Jeff Handley Joe Sonnefeldt Janice MacDonald FROM THE VICE-PRESIDENT CONTRACT DEPARTMENT Leo Murphy – Vice-President ASSISTANTS TO THE PRESIDENT - JURISDICTIONS FROM THE SECRETARY-TREASURER Leo Murphy - Vice-President Supervisor - Entire jurisdiction including theaters (Cell Phone: 773-569-8523) Dean Rolando CFM MUSICIANS Recordings, Transcriptions, Documentaries, Etc. (Cell Phone: 708-380-6219) DELEGATES TO CONVENTIONS OF THE RESOLUTION ILLINOIS STATE FEDERATION OF LABOR AND CONGRESS OF INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATIONS Terryl Jares Leo Murphy WHO, WHERE, WHEN B.J. Levy DELEGATES TO CHICAGO FEDERATION OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL UNION COUNCIL Rich Daniels Leo Murphy LOOKING BACK Terryl Jares DELEGATES TO CONVENTIONS OF THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF MUSICIANS Rich Daniels B.J. Levy HEALTH CARE UPDATE Terryl Jares Leo Murphy Alternate: Charles Schuchat PUBLISHER, THE INTERMEZZO FAIR EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES COMMITTEE Terryl Jares CO-EDITORS, THE INTERMEZZO Sharon Jones Leo Murphy PRESIDENTS EMERITI CFM SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS Gary Matts Ed Ward VICE-PRESIDENT EMERITUS Tom Beranek OBITUARIES SECRETARY-TREASURER EMERITUS Spencer Aloisio BOARD OF DIRECTORS EMERITUS ADDRESS AND PHONE CHANGES Bob Lizik Open Daily, except Saturday, Sunday and Holidays Office Hours 9 A.M. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Jazzletter P-Q Ocrober 1986 P 5Jno;..1O

Jazzletter P-Q ocrober 1986 P 5jNo;..1o . u-1'!-an J.R. Davis,.Bill Davis, Rusty Dedrick, Buddy DeFranco, Blair The Readers . Deiermann, Rene de Knight,‘ Ron Della Chiesa (WGBH), As of August 25, I986, the JazzIetrer’s readers were: Louise Dennys, Joe Derise, Vince Dellosa, Roger DeShon, Michael Abene, John Abbott, Mariano F. Accardi, Harlan John Dever, Harvey Diamond, Samuel H. Dibert’, Richard Adamcik, Keith Albano, Howard Alden, Eleanore Aldrich, DiCarlo, Gene DiNovi, Victor DiNovi, Chuck Domanico, Jeff Alexander, Steve Allen, Vernon Alley, Alternate and Arthur Domaschenz, Mr. and Mrs. Steve Donahue, William E. Independent Study Program, Bill Angel, Alfred Appel J r, Ted Donoghue, Bob Dorough, Ed Dougherty, Hermie Dressel, Len Arenson, Bruce R. Armstrong, Jim Armstrong, Tex Arnold, Dresslar, Kenny Drew, Ray Drummond, R.H. Duffield, Lloyd Kenny Ascher, George Avakian, Heman B. Averill, L. Dulbecco, Larry Dunlap, Marilyn Dunlap, Brian Duran, Jean Bach, Bob Bain, Charles Baker (Kent State University Eddie Duran, Mike Dutton (KCBX), ' School of Music), Bill Ballentine, Whitney Balliett, Julius Wendell Echols, Harry (Sweets) Edison,Jim_Eigo, Rachel Banas, Jim Barker, Robert H. Barnes, Charlie Barnet, Shira Elkind-Tourre, Jack Elliott, Herb Ellis, Jim Ellison, Jack r Barnett, Jeff Barr, E.M. Barto Jr, Randolph Bean, Jack Ellsworth (WLIM), Matt Elmore (KCBX FM), Gene Elzy Beckerman, Bruce B. Bee, Lori Bell, Malcolm Bell Jr, Carroll J . (WJR), Ralph Enriquez, Dewey Emey, Ricardo Estaban, Ray Bellis MD, Mr and Mrs Mike Benedict, Myron Bennett, Dick Eubanks (Capital University Conservatory of Music), Gil Bentley, Stephen C. Berens MD, Alan Bergman, James L. Evans, Prof Tom Everett (Harvard University), Berkowitz, Sheldon L. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2431 HON

November 15, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E2431 their staff on many of our most critical edu- Chicago reached the top of the charts with fa- In 1959, he was appointed by U.S. Presi- cational issues. In the past 10 years, she has vorites such as ‘‘If You Leave Me Now,’’ ‘‘Hard dent Dwight D. Eisenhower to serve as special specialized in elementary and secondary edu- to Say I’m Sorry,’’ and ‘‘Look Away.’’ In addi- assistant to U.S. Secretary of State John Fos- cation, including No Child Left Behind. Sandra tion to their incredible commercial success, ter Dulles. A year later, he ran and was elect- was involved in helping to pass NCLB and has Chicago has garnered considerable respect ed to the U.S. House of Representatives from kept the lines of communication open between among critics and has won numerous awards, the 10th Congressional District of Pennsyl- the Executive and Legislative branches of including three Grammy Awards as well as a vania. Government. Favorite Rock Group award at the American In 1962, he was elected governor of the Sandra is a career civil servant who knows Music Awards. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and, during that Federal education policy matters. She has Awards and honors aside, Chicago has a his term, he signed into law sweeping reforms served under administrations of both parties special gift for bringing people together, some- in the State’s educational system including and has consistently received internal recogni- thing I have personally experienced. My wife, creation of the State community college sys- tion for her professionalism and commitment Judy, and I are long-time fans of the band, tem, the State board of education and the to excellence. -

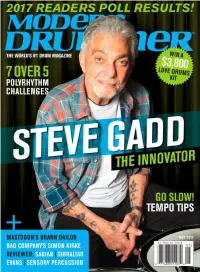

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

Winter 2014-2015 PDF Version

imagesBOULDER COUNTY PARKS AND OPEN SPACE news properties nature history events winter 2014-15 Images Artist-in-Residence at volume 36, number 4 Th e mission of the Boulder County Parks Caribou Ranch and Open Space Department is to conserve natural, cultural and agricultural resources and provide public uses that refl ect sound Caribou Ranch was, at one time, home to an artistic endeavor: the Caribou Ranch resource management and community values. recording studio. Th is studio once hosted hundreds of musicians in the 70s and 80s COVER ART: Walker Ranch Homestead, before a fi re damaged the structure in 1985. Michael Jackson, Carol King, Elton John, photo by Barry Shook U2 and the Beach Boys are just some of the artists who drew inspiration from living PHOTOGRAPHS & ILLUSTRATIONS and recording in the mountains in Boulder County. With a similar concept in mind, the Volunteer . Artist-in-Residence (AiR) Program of Caribou Ranch is now a way for artists of many Elizabeth Etzel and Fletcher Jacobs genres to fi nd inspiration in Boulder County’s natural beauty. South Boulder Creek . Kristen Turner Elk Herd . .Cathy Bryarly Th e AiR Program gives county residents a tangible connection to today’s artists— Level 3 Partners . .Craig Sommers not only musicians, but painters, illustrators, photographers, visual/fi lm artists, sculp- Frosty Spiderweb . Elizabeth Etzel tors, performers, poets, writers, composers Owl . .Janis Whisman and craft s/artisans, too. Junior Rangers . Graham Fowler Th e program also gives artists an NATURE DETECTIVES opportunity to experience open space in a Katherine Young and Deborah Price setting tailored to the artist’s needs. -

Indices for Alley Sing-A-Long Books

INDICES FOR ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOKS Combined Table of Contents Places Index Songs for Multiple Singers People Index Film and Show Index Year Index INDICES FOR THE UNOFFICIAL ALLEY SING-A-LONG BOOKS Acknowledgments: Indices created by: Tony Lewis Explanation of Abbreviations (w) “words by” (P) “Popularized by” (CR) "Cover Record" i.e., a (m) “music by” (R) “Rerecorded by” competing record made of the same (wm) “words and music by” (RR) “Revival Recording” song shortly after the original record (I) “Introduced by” (usually the first has been issued record) NARAS Award Winner –Grammy Award These indices can be downloaded from http://www.exelana.com/Alley/TheAlley-Indices.pdf Best Is Yet to Come, The ............................................. 1-6 4 Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea .................. 2-6 nd Bewitched .................................................................... 1-7 42 Street (see Forty-Second Street) ........................ 2-20 Beyond the Sea ............................................................ 2-7 Bicycle Built for Two (see Daisy Bell) ..................... 2-15 A Big Spender ................................................................. 2-6 Bill ............................................................................... 1-7 A, You’re Adorable (The Alphabet Song) .................. 1-1 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home ............... 1-8 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The ........................................ 1-1 Black Coffee ............................................................... -

Grammy Hall of Fame® Welcomes Recordings by Neil Diamond, Eurythmics, Elton John, Joni Mitchell, Nancy Sinatra and More As 2020 Inductions

GRAMMY HALL OF FAME® WELCOMES RECORDINGS BY NEIL DIAMOND, EURYTHMICS, ELTON JOHN, JONI MITCHELL, NANCY SINATRA AND MORE AS 2020 INDUCTIONS 25 RECORDINGS ADDED TO ICONIC CATALOG RESIDING AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM® SANTA MONICA, CALIF. (JAN. 14, 2020) — The Recording Academy® welcomes the newest inductions to its distinguished GRAMMY Hall Of Fame®, continuing its ongoing commitment to preserving and celebrating timeless recordings. This year’s additions recognize a diverse range of both single and album recordings at least 25 years old that exhibit qualitative or historical significance. Recordings are reviewed each year by a special member committee comprised of eminent and knowledgeable professionals from all branches of the recording arts, with final approval by the Recording Academy's National Board of Trustees. With 25 new titles, the Hall, now in its 47th year, currently totals 1,113 recordings. The 2020 GRAMMY Hall Of Fame inductions are available to stream via a playlist here. “Each year it is our distinct privilege to preserve a piece of cultural and music history with our GRAMMY Hall Of Fame inductions,” said Deborah Dugan, President/CEO of the Recording Academy. “We are so honored to welcome these timeless masterpieces to our growing catalog of iconic recordings that serve as a beacon of music excellence and diverse expression that will forever impact and inspire generations of creators.” The 2020 GRAMMY Hall Of Fame inductees range from Neil Diamond's "Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good)" to Joni Mitchell's Clouds. The list also features Eurhythmics' "Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)," Elton John's "Tiny Dancer," Devo's Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!, Swan Silvertones' "Oh Mary Don't You Weep," and Public Enemy's It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back. -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Recital Report

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1975 Recital Report Robert Steven Call Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Call, Robert Steven, "Recital Report" (1975). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 556. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/556 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECITAL REPORT by Robert Steven Call Report of a recital performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OP MUSIC in ~IUSIC UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1975 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to expr ess appreciation to my private music teachers, Dr. Alvin Wardle, Professor Glen Fifield, and Mr. Earl Swenson, who through the past twelve years have helped me enormously in developing my musicianship. For professional encouragement and inspiration I would like to thank Dr. Max F. Dalby, Dr. Dean Madsen, and John Talcott. For considerable time and effort spent in preparation of this recital, thanks go to Jay Mauchley, my accompanist. To Elizabeth, my wife, I extend my gratitude for musical suggestions, understanding, and support. I wish to express appreciation to Pam Spencer for the preparation of illustrations and to John Talcott for preparation of musical examp l es. iii UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC 1972 - 73 Graduate Recital R. -

CHICAGO TRANSIT AUTHORITY 50 Th ANNIVERSARY REMIX

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] CHICAGO TRANSIT AUTHORITY 50 th ANNIVERSARY REMIX Chicago feiern das 50-jährige Jubiläum ihres bahnbrechenden Debüts mit einer neu abgemischten Version ihres 2-fach Platin-ausgezeichneten Doppelalbums LOS ANGELES – Chicagos Debütalbum Chicago Transit Authority (bei Erscheinen noch selbstbetitelt) war eine bahnbrechende Doppel-LP, die das einfallsreiche Songwriting der Band, ihre meisterliche Musikalität und eine Genre-übergreifende Mixtur aus Rock, Jazz, Funk und Pop unter Beweis stellte. In Anerkennung seines prägenden Einflusses wurde das Album 2014 in die Grammy Hall of Fame aufgenommen. Anlässlich des 50. Jubiläums des Albums haben sich Chicago mit Toningenieur Tim Jessup zusammengetan, um das gesamte Album neu abzumischen. CHICAGO TRANSIT AUTHORITY (50th ANNIVERSARY REMIX) erscheint am 30. August auf CD und Doppel-LP auf 180g-Vinyl. Es wird auch eine nummerierte Limited Edition des 2LP-Sets auf Gold-Vinyl geben, die über rhino.com erhältlich ist. Das neu abgemischte Album wird am 30.August auch als Download und Stream veröffentlicht. Ursprünglich veröffentlicht am 28. April 1969, stieg Chicago Transit Authority in die US-Charts ein, erreichte Doppel- Platin und erhielt eine Grammy-Nominierung als „Best New Artist“. Das Werk erreichte zudem das seltene Alleinstellungsmarkmal, sich ganze drei Jahre (171 Wochen) in den US-Charts zu halten – zur damaligen Zeit ein neuer Rekord. Das zeitlose Doppelalbum enthält einige der unvergesslichsten Hits der Band: „Beginnings”, „Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” und „Questions 67 and 68”. Es enthält außerdem das unverkennbare Gitarrenspiel des 1978 verstorbenen Terry Kath auf „South California Purple”, „Free Form Guitar” und ein gleißendes Cover von „I’m A Man”.