Early Modern Romance and Poetic Futility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Apish Art': Taste in Early Modern England

‘THE APISH ART’: TASTE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND ELIZABETH LOUISE SWANN PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF YORK ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JULY 2013 Abstract The recent burgeoning of sensory history has produced much valuable work. The sense of taste, however, remains neglected. Focusing on the early modern period, my thesis remedies this deficit. I propose that the eighteenth-century association of ‘taste’ with aesthetics constitutes a restriction, not an expansion, of its scope. Previously, taste’s epistemological jurisdiction was much wider: the word was frequently used to designate trial and testing, experiential knowledge, and mental judgement. Addressing sources ranging across manuscript commonplace books, drama, anatomical textbooks, devotional poetry, and ecclesiastical polemic, I interrogate the relation between taste as a mode of knowing, and contemporary experiences of the physical sense, arguing that the two are inextricable in this period. I focus in particular on four main areas of enquiry: early uses of ‘taste’ as a term for literary discernment; taste’s utility in the production of natural philosophical data and its rhetorical efficacy in the valorisation of experimental methodologies; taste’s role in the experience and articulation of religious faith; and a pervasive contemporary association between sweetness and erotic experience. Poised between acclaim and infamy, the sacred and the profane, taste in the seventeenth century is, as a contemporary iconographical print representing ‘Gustus’ expresses it, an ‘Apish Art’. My thesis illuminates the pivotal role which this ambivalent sense played in the articulation and negotiation of early modern obsessions including the nature and value of empirical knowledge, the attainment of grace, and the moral status of erotic pleasure, attesting in the process to a very real contiguity between different ways of knowing – experimental, empirical, textual, and rational – in the period. -

Joan Copjec-Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists

Read My Desire Lacan against the Historicists Joan Copjec An OCTOBER Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 1994 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Bembo by DEKR Corporation and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copjec, Joan. Read my desire: Lacan against the historicists I Joan Copjec. p. cm. "Many of the chapters in this book appeared in earlier versions as essays in various journals and books"-T.p. verso. "An October book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-03219-8 1. Psychoanalysis and culture. 2. Desire. 3. Historicism. 4. Lacan, Jacques, 1901- 5. Foucault, Michel. I. Title. BFI75. 4. C84C66 1994 150. 19'5-dc20 94-383 CIP Many of the chapters in this book appeared in earlier versions as essays in various journals and books. Chapters 2, 4, and 5 were published in October 49 (Summer 1989); October 50 (Fall 1989); and October 56, a special issue on "Rendering the Real," edited by Parveen Adams (Spring 1991), respectively. Chapter 3 was published in Between Feminism and Psy choanalysis, edited by Teresa Brennan (London and New York: Routledge, 1989). Chapter 6 appeared in a special issue of New Formations (Summer 1991), "On Democracy," edited by Erica Carter and Renata Salecl. Chapter 7 was an essay in Shades of Noir: A Reader (London and New York: Verso, 1993), which I edited. -

THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY: THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE E. REID (Under the Direction of Sujata Iyengar) ABSTRACT This dissertation approaches the print book as an epistemologically troubled new media in early modern English culture. I look at the visual interface of emblem books, almanacs, book maps, rhetorical tracts, and commonplace books as a lens for both phenomenological and political crises in the era. At the same historical moment that print expanded as a technology, competing concepts of sight took on a new cultural prominence. Vision became both a political tool and a religious controversy. The relationship between sight and perception in prominent classical sources had already been troubled: a projective model of vision, derived from Plato and Democritus, privileged interior, subjective vision, whereas the receptive model of Aristotle characterized sight as a sensory perception of external objects. The empirical model that assumes a less troubled relationship between sight and perception slowly advanced, while popular literature of the era portrayed vision as potentially deceptive, even diabolical. I argue that early print books actively respond to these visual controversies in their layout and design. Further, the act of interpreting different images, texts, and paratexts lends itself to an oscillation of the reading eye between the book’s different, partial components and its more holistic message. This tension between part and whole appears throughout these books’ technical apparatus and ideological concerns; this tension also echoes the conflict between unity and fragmentation in early modern English national politics. Sight, politics, and the reading process interact to construct the early English print book’s formal aspects and to pull these formal components apart in a process of biblioclasm. -

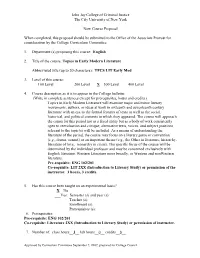

LIT 372 Topics in Early Modern Literature

John Jay College of Criminal Justice The City University of New York New Course Proposal When completed, this proposal should be submitted to the Office of the Associate Provost for consideration by the College Curriculum Committee. 1. Department (s) proposing this course: English 2. Title of the course: Topics in Early Modern Literature Abbreviated title (up to 20 characters): TPCS LIT Early Mod 3. Level of this course: ___100 Level ____200 Level ___X__300 Level ____400 Level 4. Course description as it is to appear in the College bulletin: (Write in complete sentences except for prerequisites, hours and credits.) Topics in Early Modern Literature will examine major and minor literary movements, authors, or ideas at work in sixteenth and seventeenth century literature with an eye to the formal features of texts as well as the social, historical, and political contexts in which they appeared. The course will approach the canon for this period not as a fixed entity but as a body of work consistently open to reevaluation and critique; alternative texts, voices, and subject positions relevant to the topic(s) will be included. As a means of understanding the literature of the period, the course may focus on a literary genre or convention (e.g., drama, sonnet) or an important theme (e.g., the Other in literature, hierarchy, literature of love, monarchy in crisis). The specific focus of the course will be determined by the individual professor and may be concerned exclusively with English literature, Western Literature more broadly, or Western and nonWestern literature. Pre-requisite: ENG 102/201 Co-requisite: LIT 2XX (Introduction to Literary Study) or permission of the instructor. -

Fredric-Jameson-Late-Marxism-Adorno-Or-The-Persistence-Of-The-Dialectic-1990.Pdf

Late Marxism ADORNO, OR, THE PERSISTENCE OF THE DIALECTIC Fredric Jameson LATE MARXISM LATE MARXISM FredricJameson THINKHI\IJICJ\L E I� �S VERSO London • New York First published by Verso 1990 © FredricJameson 1990 This eclition published by Verso 2007 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 57 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014-4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-575-3 ISBN-10: 1-84467-575-0 BritishLibrary Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Printed in the UK by Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey For PerryAnderson Contents A Note on Editions and Translations lX INTRODUCTION Adorno in the Stream of Time PART I BalefulEnchantments of the Concept I Identity and Anti-Identity I5 2 Dialectics and the Extrinsic 25 3 Sociologyand the Philosophical Concept 35 4 The Uses and Misuses of Culture Critique 43 5 Benjamin and Constellations 49 6 Models 59 7 Sentences and Mimesis 63 8 Kant and Negative Dialectics 73 9 The Freedom Model 77 IO The History Model 88 II Natural History 94 I2 The Metaphysics Medel III viii CONTENTS PART II Parable of the Oarsmen I Biastowards the Objective I23 2 The Guilt of Art I27 3 Vicissitudes of Culture on the Left I39 4 MassCulture asBig Business 145 5 The Culture Industry asNarrative 151 PART III Productivities of the Monad I Nominalism 157 2 The Crisis of Schein 165 3 Reification 177 4 The Monad as an Open Closure 182 5 Forces of Production 189 6 Relations of Production 197 7 The Subject, Language 202 8 Nature 212 9 Truth-Content and Political Art 220 CONCLUSIONS Adorno in the Postmodern 227 Notes 25J Index 262 A Note on Editions and Translations I have here often retranslated quotes from Adorno's works afresh (without specific indication). -

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’Ichi)

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) On the Study of Early Modern“ Elegant” Literature Suzuki Ken’ichi On 21 November 2014, I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to talk about my past research at the Research Center for Science Systems affiliated to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. There follows a summary of my talk. (1)Elucidating the distinctive qualities of early-Edo 江戸 literature, with a special focus on “elegant” or “refined”(ga 雅)literature, such as the poetry circles of the emperor Go-Mizunoo 後水尾 and the literary activities of Hayashi Razan 林羅山 . The importance of the study of “elegant” literature ・Up until around the 1970s interest in the field of early modern, or Edo-period, literature concentrated on figures such as Bashō 芭蕉,Saikaku 西鶴,and Chikamatsu 近松 of the Genroku 元禄 era(1688─1704)and Sanba 三馬,Ikku 一 九,and Bakin 馬 琴 of the Kasei 化 政 era(1804─30), and the literature of this period tended to be considered to possess a high degree of “common” or “popular”(zoku 俗)appeal. This was linked to a tendency, influenced by postwar views of history and literature, to hold in high regard that aspect of early modern literature in which “commoners resisted the oppression of the feudal 39 On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) system.” But when considered in light of the actual situation at the time, there can be no doubt that ga literature in the form of poetry written in both Japanese (waka 和歌)and Chinese(kanshi 漢詩), with its strong traditions, was a major presence in terms of both its authority and the formation of literary currents of thought. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Marie Weixel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. John Watkins, Adviser April 2009 © Elizabeth Marie Weixel, 2009 i Acknowledgements In such a wood of words … …there be more ways to the wood than one. —John Milton, A Brief History of Moscovia (1674) —English proverb Many people have made this project possible and fruitful. My greatest thanks go to my adviser, John Watkins, whose expansive expertise, professional generosity, and evident faith that I would figure things out have made my graduate studies rewarding. I count myself fortunate to have studied under his tutelage. I also wish to thank the members of my committee: Rebecca Krug for straightforward and honest critique that made my thinking and writing stronger, Shirley Nelson Garner for her keen attention to detail, and Lianna Farber for her kind encouragement through a long process. I would also like to thank the University of Minnesota English Department for travel and research grants that directly contributed to this project and the Graduate School for the generous support of a 2007-08 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. Fellow graduate students and members of the Medieval and Early Modern Research Group provided valuable support, advice, and collegiality. I would especially like to thank Elizabeth Ketner for her generous help and friendship, Ariane Balizet for sharing what she learned as she blazed the way through the dissertation and job search, Marcela Kostihová for encouraging my early modern interests, and Lindsay Craig for his humor and interest in my work. -

Death Not Life, Or, the Destruction of the Wicked

3T . &3fi 355 185$ lift ' : //':;„ || f • ^ moil mm: LIBRARY OF THE LATE os. 1>. f(ev. Tl. ^•l 1 ,tieniore. D. Gift of Mrs. Whittemore, DEATH NOT LIFE: oa TUB DESTRUCTION OF THE WICKED (commonly called annihilation,) ESTABLISHED, AND ENDLESS MISERY DISPROVED, BY A. COLLECTION AND EXPLANATION OF ALL PASSAGES ON FUTURE PUNISHMENT, TO 'WHICH IS ADDED A REVIEW OF DR. E. BEE CHER'S CONFLICT OF AGES, AND JOHN FOSTER'S LETTER. By JACOB SLAIN", BAPTIST MINISTER OF BUFFALO, N. Y. "For all the wicked will God destroy."—Ps. 145: 20. "For yet a little while, and the wicked shall not be."—Ps. 37 : 10. "They shall be as though they had not been."— Obadiah 16. Jor they 44 shall be punished with everlasting destruction'* 2d Thess. 1 : 9. EIGHTH EDITION. BOSTON: PUBLISHED BY JOHN P. JEWETT & CO. No. 20 Washington- Street. 1 8 58. —— — 3T JB-fJ* INDEX. 0 / TS ? Introductiox, page 3— 8. Importance of the subject, p. 4. Brief history of the doctrine of destruction, 6. Objections to investigate removed, 7. Chap. I. —The doctrine of destruction proved, 9. ' Immortal soul* not iu the Bible, 10. Twenty terras, as "die, perish, destroy, burn up," <fec, used 200 times to prove destruction, 10. Their Bible • meaning, 20. Ten texts for restoration, as proving destruction, 21. Life and death not figurative, 21. What was lost by the fall, 26. wholesale perversion, 23. All the Bible proof of immortality, 23 Error in our translation, 30. Meaning of soul and spirit, 30. Chap. II. —Metaphysical proof of immortality exploded, 33. -

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Thomas Gaubatz All rights reserved ABSTRACT Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz This dissertation examines the ways in which the narrative fiction of early modern (1600- 1868) Japan constructed urban identity and explored its possibilities. I orient my study around the social category of chōnin (“townsman” or “urban commoner”)—one of the central categories of the early modern system of administration by status group (mibun)—but my concerns are equally with the diversity that this term often tends to obscure: tensions and stratifications within the category of chōnin itself, career trajectories that straddle its boundaries, performative forms of urban culture that circulate between commoner and warrior society, and the possibility (and occasional necessity) of movement between chōnin society and the urban poor. Examining a range of genres from the late 17th to early 19th century, I argue that popular fiction responded to ambiguities, contradictions, and tensions within urban society, acting as a discursive space where the boundaries of chōnin identity could be playfully probed, challenged, and reconfigured, and new or alternative social roles could be articulated. The emergence of the chōnin is one of the central themes in the sociocultural history of early modern Japan, and modern scholars have frequently characterized the literature this period as “the literature of the chōnin.” But such approaches, which are largely determined by Western models of sociocultural history, fail to apprehend the local specificity and complexity of status group as a form of social organization: the chōnin, standing in for the Western bourgeoisie, become a unified and monolithic social body defined primarily in terms of politicized opposition to the ruling warrior class. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42451-6 — Affect and Literature Edited by Alex Houen Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42451-6 — Affect and Literature Edited by Alex Houen Index More Information Index Adorno, Theodor happening and haphazardness in relation affect in his writing, 104 to, 20 culture industry, on, 104, 106 knowledge distinguished, 159 disgust, on, 108, 113 persistence of, 309 emotion and art in relation, 268 postcolonial. See postcolonial affect English translation of his writing, 104, 107, 109 reader’s affective stance, 18, 20, 22 false pleasure, on, 108 scope of current study, 23 ‘fun,’ use of word, 107 secondary affect. See secondary affect Georg Lukács, and, 113 sensation of, 176 happiness, on, 109 social aspect of, 19 Karl Marx, on, 111 space and time in relation to, 2, 3, 14 manufacture of fun, on, 106 subaltern. See subaltern affect need, on, 104 theories of, 2 universal history, on, 105 theory. See affect theory vision of emancipated humanity, 111, 113 universalism of, 33 aesthetics universalization by ‘psy’ disciplines, 175 affect and, 9, 17, 19 affect theory affect theory and, 49–51 applications. See CGI effects; crisis fiction; crying as aesthetic response, 62–63 Descartes, René; digital media; definition of, 51–52 environmental affect; War on Terror knowledge and, 50, 52 branches of, 250 laughter and, 232 critical affect studies, 85 sympathy and, 62 developments in. See antihumanism; Davis, affect Bette; early modern writing; Irish novels; affective life. See affective life laughter; postcolonial affect; subaltern basic trio of affects (desire, joy, and affect sadness), 67 early modern writing, and. See early modern becoming and being in relation to, 18 writing body and mind in relation to, 2, 3, 5, 16, Enlightenment aesthetics, and, 49, 52 160 Leys’s ‘new paradigm’ of, 159, 173 Cartesian. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen.