Track Layout and the Basics of Wagering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

How a Pointless Race Can Have the Best of Purposes

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2020 INDEPENDENCE HALL STEPS UP IN DAVIS HOW A POINTLESS RACE by Joe Bianca Undefeated and impressive in all three of his career starts thus CAN HAVE THE BEST OF far, Independence Hall (Constitution) has earned respect as one PURPOSES of the top early choices for the GI Kentucky Derby. Saturday, fans will get a much clearer picture of whether that stature is justified, as the Mike Trombetta trainee heads south to take on a quality field in the GIII Sam F. Davis S. at Tampa Bay Downs. Sent off as a 7-5 favorite debuting in a seven-furlong event on the GI Pennsylvania Derby undercard at Parx, the dark bay broke slowly, but recovered quickly and ran away to an easy 4 3/4-length score. Stepped up into stakes company in the GIII Nashua S. Nov. 3 at Aqueduct, the $100,000 Keeneland September grad produced arguably the most impressive performance of any 2-year-old in 2019 when blowing the doors off his competition with a 12 1/4-length romp. Cont. p5 Peter Eurton | Horsephotos IN TDN EUROPE TODAY by Chris McGrath BARBOTTIERE TRIUMPHANT WITH GROUP 1 RECRUITS Peter Eurton knows. He has been training since 1989, after all: Haras de la Barbottiere debuts Group 1 winners Donjuan the year of Sunday Silence and Easy Goer. One, on the West Triumphant and Robin of Navan on its dual purpose roster this Coast, began his sophomore campaign in an allowance race at year. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. -

We Cover the Risk So You Can Focus on the Reward

CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 1 WE COVER THE RISK SO YOU CAN FOCUS ON THE REWARD. You’ve worked hard for your assets. Protect them against misfortune. KUDA COVERS YOUR RACEHORSE: Mortality Cover, Lifesaving Surgery and Critical Care Cover, Medical Care Cover, and Public Liability Cover. KUDA COVERS EVERYTHING ELSE: We cover all your valued assets: Personal and Commercial Insurance, Sport Horse Insurance, and Game and Wildlife Insurance. If you trust us with covering your valued thoroughbred, you can trust us to cover all your assets. CALL US TODAY FOR COVER FROM THE LUXURY LIFESTYLE INSURANCE SPECIALISTS. WÉHANN SMITH +27 82 337 4555 JO CAMPHER +27 82 334 4940 ninety9cents 42088T ninety9cents Kuda Holdings - Authorised Financial Services Provider, FSP number: 38382. All policies are on a Co-Insurance basis between Infiniti Insurance and various syndicates of Lloyds. Kuda Holdings approved Lloyds coverholder PIN 112897CJS. 2 CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 42088T Kuda Turf Directory Print Ad Luxury lifestyle insurance 210 x 148 FA2.indd 1 2018/12/19 2:48 PM CRT - Mixed Sale February 2019 3 VENDOR INDEX Lot Colour Sex Breeding On Account of Cheveley Stud. (As Agent) 43 Chestnut Mare Oxbow Lake by Fort Wood (USA) 45 Chestnut Mare Tippuana by Fort Wood (USA) 51 Chestnut Mare Silent Treatment by Jet Master 56 Chestnut Mare Rachel Leigh by Fort Wood (USA) 70 Bay Mare Miss K by Kahal (GB) 72 Chestnut Mare Giant's Slipper (AUS) by Giant's Causeway (USA) 76 Grey Mare Ado Annie by Trippi (USA) 84 Bay Mare Lavender Bells by Al Mufti (USA) On Account of Harold Crawford Racing. -

Sweet Melania Headlines Friday's Lake George Stakes

ftboa.com • Thursday • August 27, 2020 FEC/FTBOA PUBLICATION DEADLINE: The Florida-bred registration deadline is Aug 31 postmarked deadline. CLICK HERE FOR LINK. SELECT FORM IN THE RIGHT COLUMN In This Issue: Rainbow 6 Jackpot Pool at $450,000 Victory Kingdom Makes Debut Long Weekend to Stick with Familiar Distance Delgado Trying for Trainer Title Born to Rein Film Headed to Ocala Lies to Call Final Week at Del Mar TOBA to Host National Awards Virtually National Museum of Racing to Reopen Healthy McCarthy Back in the Irons Preakness to Join Breeders’ Cup Series Sweet Melania/JOE LABOZZETTA PHOTO Track Results & Entries Sweet Melania Headlines Florida Stallion Progeny List Florida Breeders’ List Friday’s Lake George Stakes Wire to Wire Business Place Florida-breds Sugar Fix, American Giant, Miss Pepina Also Set Featured Advertisers BY RYAN MARTIN, layoff while registering a career-best 87 NYRA PRESS OFFICE______________ Beyer Speed Figure. Florida Department of Agriculture The American Pharoah chestnut began SARATOGA SPRINGS, NY—Robert and her career on the main track but made her FTBOA Lawana Low's Sweet Melania will attempt third career start a winning one when Ocala Breeders’ Feed & Supply to keep her consistent record intact when debuting on grass over the Spa's inner turf she headlines Friday's 25th running of the last July. Sweet Melania followed up with Seminole Feed $100,000 Lake George Stakes (Grade 3) a runner-up effort in the P.G. Johnson for 3-year-old fillies going one mile over Stakes at Saratoga before a victory in the the inner turf while three Florida-breds Grade 2 Jessamine at Keeneland. -

2011/B/54 Annual Returns Received Between 11-Nov-2011 and 17-Nov-2011 Index of Submission Types

ISSUE ID: 2011/B/54 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 INDEX OF SUBMISSION TYPES B1B - REPLACEMENT ANNUAL RETURN B1C - ANNUAL RETURN - GENERAL B1AU - B1 WITH AUDITORS REPORT B1 - ANNUAL RETURN - NO ACCOUNTS CRO GAZETTE, FRIDAY, 18th November 2011 3 ANNUAL RETURNS RECEIVED BETWEEN 11-NOV-2011 AND 17-NOV-2011 Company Company Documen Date Of Company Company Documen Date Of Number Name t Receipt Number Name t Receipt 1246 THE LEOPARDSTOWN CLUB LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 17811 VITA CORTEX (DUBLIN) LIMITED B1 27/10/2011 1858 MACDLAND LIMITED B1C 12/10/2011 17952 MARS NOMINEES LIMITED B1C 21/10/2011 1995 THOMAS CROSBIE HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18005 THE ST. JOHN OF GOD DEVELOPMENT B1C 28/10/2011 3166 JOHNSON & PERROTT, LIMITED B1C 26/10/2011 COMPANY LIMITED 3446 WATERFORD NEWS & STAR LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 18099 GERALD STANLEY & SON LIMITED B1C 06/11/2011 3567 DPN NO. 3 B1AU 17/10/2011 18422 MANGAN BROS. HOLDINGS B1AU 20/10/2011 3602 BAILEY GIBSON LIMITED B1C 24/10/2011 18444 DEHYMEATS LIMITED B1C 17/10/2011 3623 ST. LUKE'S HOME, CORK B1C 27/10/2011 18483 COEN STEEL (TULLAMORE) LIMITED B1C 27/10/2011 (INCORPORATED) 18543 BOART LONGYEAR LIMITED B1C 25/10/2011 4091 THE TIPPERARY RACE COMPANY B1C 14/10/2011 18585 LYONS IRISH HOLDINGS LIMITED B1C 11/10/2011 PUBLIC LIMITED COMPANY 18686 BOS (IRELAND) FUNDING LIMITED B1C 20/10/2011 4956 MCMULLAN BROS., LIMITED B1C 18/10/2011 18692 THE KILNACROTT ABBEY TRUST B1C 27/10/2011 6010 VERITAS COMMUNICATIONS B1C 24/10/2011 19441 D. -

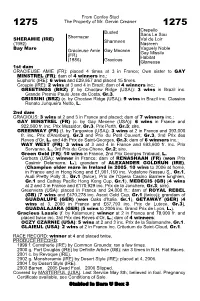

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

From Aga Khan Studs Shirley Heights Mill Reef Hardiemma

From Aga Khan Studs 1363 1363 Mill Reef Shirley Heights Hardiemma Darshaan Abdos ALASANA (IRE) Delsy (1991) Kelty Nasrullah Bay Mare Red God Aleema Spring Run (1978) Relko Alannya Nucciolina 1st dam ALEEMA: 2 wins at 3 in France and placed twice; dam of 9 winners inc.: ALTAYAN (c. by Posse (USA)): 3 wins at 3 in France and £140,720 inc. Prix du Conseil de Paris, Gr.2 and Prix Maurice de Nieuil, Gr.2, placed 3 times viz. 2nd Prix du Jockey Club Lancia, Gr.1, Prix de Suresnes, L. and 4th Grand Prix de Saint-Cloud, Gr.1; sire. ALTASHAR (c. by Vayrann): 2 wins in France inc. Grand Prix de Vichy, Gr.3. 2nd dam ALANNYA (FR): 2 wins at 2 and 3 in France inc. Prix La Camargo, L., placed viz. 3rd Prix de la Grotte, Gr.3 and Prix Penelope, Gr.3; dam of 9 winners inc.: ALIYA (IRE) (f. by Darshaan): 2 wins at 3 and £21,375 inc. Ardilaun House Hotel Oyster S., L., placed inc. 2nd Challenge S., L.; dam of 2 winners. ALIYSA (f. by Darshaan): Champion 3yr old filly in England in 1989, 2 wins at 2 and 3 and £31,925 inc. Marley Roof Tile Oaks Trial S., L., placed viz. 2nd Kildangan Stud Irish Oaks, Gr.1; dam of 4 winners inc.: DESERT STORY (IRE): 3 wins at 2 and 3 and £110,846 inc. City Index Craven S., Gr.3 and Vodafone Horris Hill S., Gr.3; sire. Alaiyda (USA): winner at 3; dam of ALAMSHAR (IRE), (Champion 3yr old in England & Ireland in 2003, 5 wins at 2 and 3 and £1,211,169 inc. -

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams

EUROPEAN PEDIGREE for TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) - Three Dams Anabaa (USA) Danzig (USA) Sire: (Bay 1992) Balbonella (FR) STYLE VENDOME (FR) (Grey 2010) Place Vendome (FR) Dr Fong (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (Grey 2004) Mediaeval (FR) (Bay filly 2015) Green Desert (USA) Danzig (USA) Dam: (Bay 1983) Foreign Courier (USA) ALABASTRINE (GB) (Grey 2000) Alruccaba Crystal Palace (FR) (Brown/Grey 1983) Allara 3Sx3D Danzig (USA) TORNEQUETA MAY (GB) (2015 filly by STYLE VENDOME (FR)), unraced in GB/IRE. 1st dam. ALABASTRINE (GB) (2000 mare by GREEN DESERT (USA)); in GB/IRE, placed once, £1,145 at 3 years, exported to France; dam of 11 known foals; 6 known runners; 4 known winners. HAIL CAESAR (IRE) (2006 gelding by MONTJEU (IRE)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £8,638 at 2 years, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £19,638 at 3 years; in Belgium, won 1 race, £1,293 at 5 years, won 2 races and placed twice, £4,084 at 6 years; in France, unplaced at 2 years, unplaced at 3 years, unplaced at 6 years, unplaced at 10 years; in GB/IRE over hurdles, won 1 race and placed 4 times, £11,137 at 4 years, placed once, £143 at 5 years; in GB/IRE over fences, placed once, £430 at 5 years, exported to Belgium. ALBASPINA (IRE) (2009 mare by SELKIRK (USA)); in GB/IRE, won 1 race, £2,264 at 2 years, placed twice, £1,819 at 3 years; dam of- Hiss Beau (QTR) (2014 filly by ROYAL APPLAUSE (GB)); in Qatar, unplaced at 3 years. -

Equine Laminitis Managing Pasture to Reduce the Risk

Equine Laminitis Managing pasture to reduce the risk RIRDCnew ideas for rural Australia © 2010 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978 1 74254 036 8 ISSN 1440-6845 Equine Laminitis - Managing pasture to reduce the risk Publication No. 10/063 Project No.PRJ-000526 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. However, wide dissemination is encouraged. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the RIRDC Publications Manager on phone 02 6271 4165. -

Hedging Your Bets: Is Fantasy Sports Betting Insurance Really ‘Insurance’?

HEDGING YOUR BETS: IS FANTASY SPORTS BETTING INSURANCE REALLY ‘INSURANCE’? Haley A. Hinton* I. INTRODUCTION Sports betting is an animal of both the past and the future: it goes through the ebbs and flows of federal and state regulations and provides both positive and negative repercussions to society. While opponents note the adverse effects of sports betting on the integrity of professional and collegiate sporting events and gambling habits, proponents point to massive public interest, the benefits to state economies, and the embracement among many professional sports leagues. Fantasy sports gaming has engaged people from all walks of life and created its own culture and industry by allowing participants to manage their own fictional professional teams from home. Sports betting insurance—particularly fantasy sports insurance which protects participants in the event of a fantasy athlete’s injury—has prompted a new question in insurance law: is fantasy sports insurance really “insurance?” This question is especially prevalent in Connecticut—a state that has contemplated legalizing sports betting and recognizes the carve out for legalized fantasy sports games. Because fantasy sports insurance—such as the coverage underwritten by Fantasy Player Protect and Rotosurance—satisfy the elements of insurance, fantasy sports insurance must be regulated accordingly. In addition, the Connecticut legislature must take an active role in considering what it means for fantasy participants to “hedge their bets:” carefully balancing public policy with potential economic benefits. * B.A. Political Science and Law, Science, and Technology in the Accelerated Program in Law, University of Connecticut (CT) (2019). J.D. Candidate, May 2021, University of Connecticut School of Law; Editor-in-Chief, Volume 27, Connecticut Insurance Law Journal. -

Wager Guide Pimlico Race Course Oct03 Preakness

1/ST BET WAGER GUIDE PREAKNESS STAKES OCT03 PIMLICO RACE COURSE THOUSAND WORDS (6/1) 5 Owner: Albaugh Family Stable & Spendthrift Farm PRIMARY Trainer: Bob Baffert Jockey: Florent Geroux STAKES NUMBER POSITIVE JESUS’ TEAM (30/1) 6 Owner: Grupo Seven C Stable Trainer: Jose D’Angelo Jockey: Jevian Toledo 145 NY TRAFFIC (15/1) Owner: John Fanelli, Cash is King, 7 LC Racing, Paul Braverman & Team Hanley Trainer: Saffie Joseph Jr. Jockey: Horacio Karamanos EXCESSION (30/1) MAX PLAYER (15/1) 1 Owner: Calumet Farm 8 Owner: George Hall & SportBLX Trainer: Steve Asmussen Thoroughbreds Jockey: Sheldon Russell Trainer: Steve Asmussen Jockey: Paco Lopez MR. BIG NEWS (12/1) AUTHENTIC (9/5) Owner: Spendthrift Farm, Owner: Allied Racing Stable, LLC 2 9 MyRaceHorse Stable, Madaket Trainer: Bret Calhoun Stables & Starlight Racing Jockey: Gabriel Saez Trainer: Bob Baffert Jockey: John Velazquez ART COLLECTOR (5/2) PNEUMATIC (20/1) 3 Owner: Bruce Lunsford 10 Owner: Winchell Thoroughbreds Trainer: Tom Drury Jr. Trainer: Steve Asmussen Jockey: Brian Hernandez Jr. Jockey: Joe Bravo SWISS SKYDIVER (6/1) LIVEYOURBEASTLIFE 4 Owner: Peter J. Callahan 11 (30/1) Trainer: Ken McPeek Owner: William H. Lawrence Jockey: Robby Albarado Trainer: Jorge Abreu Jockey: Trevor McCarthy 1ST.COM/BET 2 MEET THE PREAKNESS CONTENDERS By Johnny D., @XBJohnnyD AUTHENTIC: He’s the wire-to-wire upset winner of the Kentucky Derby at over 8-1 odds for 6-time roses-wearing trainer Bob Baffert. The trainer’s record with Derby winners returning in Preakness is unblemished—5-for-5. Baffert won additional Preakness scrums with Derby disappointments Point Given and Lookin At Lucky for a record 7 wins in the traditional second leg of the Triple Crown. -

PUBLIC CONSULTATION on PROPOSED AMENDMENTS to LAWS GOVERNING GAMBLING ACTIVITIES 1. the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) Is Seekin

PUBLIC CONSULTATION ON PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO LAWS GOVERNING GAMBLING ACTIVITIES 1. The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) is seeking feedback on proposed amendments to laws governing gambling. Background 2. Singapore adopts a strict but practical approach in its regulation of gambling. It is not practical, nor desirable in fact, to disallow all forms of gambling, as this will drive it underground, and cause more law and order issues. Instead, we license or exempt some gambling activities, with strict safeguards put in place. Our laws governing gambling seek to maintain law and order, and minimise social harm caused by problem gambling. 3. Our approach has delivered good outcomes. First, gambling-related crimes remain low. Casino crimes have contributed to less than 1% of overall crime since the Integrated Resorts started operations in 2010. The number of people arrested for illegal gambling activities has remained stable from 2011 to 2020. Second, problem gambling remains under control. Based on the National Council on Problem Gambling's Gambling Participation Surveys that are conducted every three years, problem and pathological gambling rates have remained relatively stable, at around 1%. 4. To continue to enjoy these good outcomes, we need to make sure that our laws and regulations can address two trends in the gambling landscape. First, advancements in technology. The internet and mobile computing have made gambling products more accessible. People can now gamble anywhere and anytime through portable devices such as smart phones. Online gambling has been on the uptrend. Worldwide revenue from online gambling is projected to almost triple, from US$49 billion in 2018 to US$135 billion in 2027.1 Second, the boundaries between gambling and gaming have blurred.