UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Molecular Mechanisms Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read the Summer 2021 Newsletter

CCR Fellows & Young Investigators Newsletter Center for Cancer Research Volume 20, Issue 3 Summer 2021 CCR-FYI Newsletter Team Special newsletter edition: 21st CCR FYI Colloquium EDITOR IN CHIEF – From Mechanisms to Therapies: Alida Palmisano Current Highlights in Cancer Research MANAGING EDITOR – Annan Timon EDITORS – Enitome Bafor Sarah Burnash Dorothy L. Butler Molly Congdon Jessica Eisenstatt Amy Funk Mary Grace Katusiime Victoria Hill Sarwat Naz Carlos Villapudua CONTRIBUTORS – Srikanta Basu Dorothy Butler Sunita Chopra Molly Congdon Mary Grace Katusiime Katelyn Ludwig Isita Jhulki Babul Ram Geraldine Vilmen In the picture above, the CCR-FYI Colloquium Planning Committee: CCR-FYI Association is Chairs: Srikanta Basu, Katelyn Ludwig. Vice Chairs: Dorothy L. Butler, Anna Ratliff. supported by the NCI Knicki Bergman, Molly Congdon, Ruchika Bhujbalrao, Vasty Osei Amponsa, Sabina Kaczanowska, Center for Cancer Training Neha Wali, Joshua Rose, Sunita Chopra, Isita Jhulki, Mary Grace Katusiime, Sumirtha Balaratnam. (CCT) and CCR Office of Not in the picture, but part of the Planning Committee: Cassey Singler, Jose Delgado the Director. Support of the CCT-Office of Training and Education, CCR-FYI SC and CBIIT was essential for the success of this event, in particular the Committee wants to thank Amy Funk, Jessica Connect with CCR-FYI Eisenstatt, Angela Jones, Robert Montano, Erika Ginsburg and Oliver Bogler. VOLUME 20 – ISSUE 3 – SUMMER 2021 While the COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a major impact on the life of many NCI fellows, we are happy to see that one of the big CCR events of the year (the CCR-FYI Colloquium) returned in 2021 after being cancelled in 2020. -

Lipid Metabolism Has Been Good to Me George M

REFLECTIONS Lipid metabolism has been good to me https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100786 George M. Carman* From the Department of Food Science and the Rutgers Center for Lipid Research, New Jersey Institute for Food, Nutrition, and Health, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA Edited by the Reflections and Classics Committee headed by Patrick Sung My career in research has flourished through hard work, program director of the National Science Foundation), supportive mentors, and outstanding mentees and collabora- encouraged me to pursue a research career in biochemistry; tors. The Carman laboratory has contributed to the under- she continues to be a mentor and friend. My MS degree standing of lipid metabolism through the isolation and advisor, John Keller, introduced me to laboratory research characterization of key lipid biosynthetic enzymes as well as and gave me an appreciation for science in a broader context through the identification of the enzyme-encoding genes. Our by encouraging me to attend meetings of the Theobald Smith findings from yeast have proven to be invaluable to understand Society for Microbiology (local branch of the American So- regulatory mechanisms of human lipid metabolism. Several ciety for Microbiology). He also encouraged me to apply to rewarding aspects of my career have been my service to the the University of Massachusetts (PhD, 1977) where Robert Journal of Biological Chemistry as an editorial board member Levin had an open graduate research position in food and Associate Editor, the National Institutes of Health as a microbiology. I did not realize that my PhD degree would be member of study sections, and national and international sci- in Food Science or that I would have to take undergraduate entific meetings as an organizer. -

Deletion of Stk11 and Fos in Mouse BLA Projection Neurons

RESEARCH ARTICLE Deletion of Stk11 and Fos in mouse BLA projection neurons alters intrinsic excitability and impairs formation of long- term aversive memory David Levitan1†*, Chenghao Liu1†, Tracy Yang1, Yasuyuki Shima1, Jian-You Lin2,3, Joseph Wachutka2, Yasmin Marrero2, Ramin Ali Marandi Ghoddousi1, Eduardo da Veiga Beltrame2, Troy A Richter1, Donald B Katz2,3, Sacha B Nelson1,3* 1Departments of Biology, Brandeis University, Waltham, United States; 2Departments of Psychology, Brandeis University, Waltham, United States; 3Volen Center for Complex Systems, Brandeis University, Waltham, United States Abstract Conditioned taste aversion (CTA) is a form of one-trial learning dependent on basolateral amygdala projection neurons (BLApn). Its underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. RNAseq from BLApn identified changes in multiple candidate learning- related transcripts including the expected immediate early gene Fos and Stk11, a master kinase of the AMP-related kinase pathway with important roles in growth, metabolism and development, but not previously implicated in learning. Deletion of Stk11 in BLApn blocked memory prior to training, but not following it and increased neuronal excitability. Conversely, BLApn had reduced excitability following CTA. BLApn knockout of a second learning-related gene, Fos, also increased excitability and impaired learning. Independently increasing BLApn excitability chemogenetically during CTA *For correspondence: also impaired memory. STK11 and C-FOS activation were independent -

Deletion of Stk11 and Fos in Mouse BLA Projection Neurons Alters Intrinsic 3 Excitability and Impairs Formation of Long-Term Aversive Memory

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/787325; this version posted November 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Deletion of Stk11 and Fos in mouse BLA projection neurons alters intrinsic 3 excitability and impairs formation of long-term aversive memory 4 5 6 Abbreviated Title: The role of Stk11 in memory formation 7 8 David Levitan2*, Chenghao Liu2*, Tracy Yang2, Yasuyuki Shima2, Jian-You Lin1, 3, Joseph 9 Wachutka1, Yasmin Marrero1, Ramin Ali Marandi Ghoddousi2, Eduardo da Veiga Beltrame1, 10 Donald B. Katz1, 3, Sacha B. Nelson2, 3 Departments of Psychology1, Biology2, and Volen Center for Complex Systems3, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts 02454, USA. 11 12 13 *D.L. and C.L. contributed equally 14 Proofs and correspondence to: 15 Sacha B Nelson, MD, PhD, Brandeis University 16 Department of Biology, MS 062, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02454, 17 Email: [email protected] 18 19 Declaration of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests. 20 Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and 21 Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) DC006666 and by NINDS NS109916. 22 23 24 25 26 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/787325; this version posted November 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

An Emerging Acral Melanoma Oncogene

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Advance Publications 2011 NUAK2: an emerging acral melanoma oncogene Takeshi Namiki1,2, Sergio G. Coelho1, Vincent J. Hearing1 1 Laboratory of Cell Biology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA 2 Department of Dermatology, Yokohama Minato Red Cross Hospital, Yokohama, Kanagawa 231-0801, Japan Correspondence to: Dr. Takeshi Namiki, email: [email protected] Keywords: NUAK2, acral melanoma, migration, metastasis, oncogene Received: September 9, 2011, Accepted: September 10, 2011, Published: September 10, 2011 Copyright: © Namiki et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT: Recent technological advances in cancer genomics make it possible to dissect complicated genomic aberrations of melanomas. In particular, several specific genomic aberrations including 11q13 amplification and KIT aberrations have been identified in acral melanomas. We recently identified NUAK2 at 1q32 as a promising oncogene in acral melanomas and reported its significant roles in tumorigenesis in melanoma cells using both in vitro and in vivo analyses. NUAK2 as a member of the AMPK family has several intriguing aspects both as an oncogene and as a tumor suppressor gene. Here we review genomic aberrations of melanomas focusing on acral melanomas to emphasize the possible roles -

Inhibition of ERK 1/2 Kinases Prevents Tendon Matrix Breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inhibition of ERK 1/2 kinases prevents tendon matrix breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L. Wunderli1,2,3, Amro A. Hussien1,2, Tino Stauber1,2, Gabriel Flückiger1,2, Maja Bollhalder1,2, Barbara Niederöst1,2, Sandro F. Fucentese1 & Jess G. Snedeker1,2* Tendon extracellular matrix (ECM) mechanical unloading results in tissue degradation and breakdown, with niche-dependent cellular stress directing proteolytic degradation of tendon. Here, we show that the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is central in tendon degradation of load-deprived tissue explants. We show that ERK 1/2 are highly phosphorylated in mechanically unloaded tendon fascicles in a vascular niche-dependent manner. Pharmacological inhibition of ERK 1/2 abolishes the induction of ECM catabolic gene expression (MMPs) and fully prevents loss of mechanical properties. Moreover, ERK 1/2 inhibition in unloaded tendon fascicles suppresses features of pathological tissue remodeling such as collagen type 3 matrix switch and the induction of the pro-fbrotic cytokine interleukin 11. This work demonstrates ERK signaling as a central checkpoint to trigger tendon matrix degradation and remodeling using load-deprived tissue explants. Tendon is a musculoskeletal tissue that transmits muscle force to bone. To accomplish its biomechanical function, tendon tissues adopt a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structure1. Te load-bearing tendon compart- ment consists of highly aligned collagen-rich fascicles that are interspersed with tendon stromal cells. Tendon is a mechanosensitive tissue whereby physiological mechanical loading is vital for maintaining tendon archi- tecture and homeostasis2. Mechanical unloading of the tissue, for instance following tendon rupture or more localized micro trauma, leads to proteolytic breakdown of the tissue with severe deterioration of both structural and mechanical properties3–5. -

Anti-STK11 / LKB1 Antibody (ARG59116)

Product datasheet [email protected] ARG59116 Package: 50 μg anti-STK11 / LKB1 antibody Store at: -20°C Summary Product Description Rabbit Polyclonal antibody recognizes STK11 / LKB1 Tested Reactivity Hu Tested Application WB Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Target Name STK11 / LKB1 Antigen Species Human Immunogen Recombinant protein corresponding to K62-C430 of Human STK11 / LKB1. Conjugation Un-conjugated Alternate Names hLKB1; Serine/threonine-protein kinase STK11; Liver kinase B1; Renal carcinoma antigen NY-REN-19; LKB1; EC 2.7.11.1; PJS Application Instructions Application table Application Dilution WB 0.1 - 0.5 µg/ml Application Note * The dilutions indicate recommended starting dilutions and the optimal dilutions or concentrations should be determined by the scientist. Calculated Mw 49 kDa Properties Form Liquid Purification Affinity purification with immunogen. Buffer 0.9% NaCl, 0.2% Na2HPO4, 0.05% Sodium azide and 5% BSA. Preservative 0.05% Sodium azide Stabilizer 5% BSA Concentration 0.5 mg/ml Storage instruction For continuous use, store undiluted antibody at 2-8°C for up to a week. For long-term storage, aliquot and store at -20°C or below. Storage in frost free freezers is not recommended. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Suggest spin the vial prior to opening. The antibody solution should be gently mixed before use. Note For laboratory research only, not for drug, diagnostic or other use. www.arigobio.com 1/3 Bioinformation Gene Symbol STK11 Gene Full Name serine/threonine kinase 11 Background This gene, which encodes a member of the serine/threonine kinase family, regulates cell polarity and functions as a tumor suppressor. -

Neuronal Migration and Protein Kinases

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector REVIEW ARTICLE published: 13 January 2015 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00458 Neuronal migration and protein kinases Toshio Ohshima* Laboratory for Molecular Brain Science, Department of Life Science and Medical Bioscience, Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan Edited by: The formation of the six-layered structure of the mammalian cortex via the inside-out Kazunori Nakajima, Keio University pattern of neuronal migration is fundamental to neocortical functions. Extracellular cues School of Medicine, Japan such as Reelin induce intracellular signaling cascades through the protein phosphorylation. Reviewed by: Migrating neurons also have intrinsic machineries to regulate cytoskeletal proteins and Mikio Hoshino, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan adhesion properties. Protein phosphorylation regulates these processes. Moreover, the Shin-ichi Hisanaga, Tokyo balance between phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is modified by extracellular cues. Metropolitan University, Japan Multipolar-bipolar transition, radial glia-guided locomotion and terminal translocation are *Correspondence: critical steps of radial migration of cortical pyramidal neurons. Protein kinases such as Toshio Ohshima, Laboratory for Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) involve these steps. Molecular Brain Science, Department of Life Science and In this review, I shall give an overview the roles of protein kinases in neuronal migration. Medical Bioscience, Waseda University, 2-2 Wakamatsu-cho, Keywords: protein phosphorylation, kinase, phosphatase, migration, cerebral cortex Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8480, Japan e-mail: [email protected] CYTOSKELETON DYNAMICS DURING NEURONAL proximal region of the leading process during the locomotion MIGRATION mode of migration (Nishimura et al., 2014). -

Regulation of the Polarity Kinases PAR-1/MARK by 14-3-3 Interaction and Phosphorylation

Research Article 4059 Regulation of the polarity kinases PAR-1/MARK by 14-3-3 interaction and phosphorylation Olga Göransson1,*,‡, Maria Deak1, Stephan Wullschleger1, Nick A. Morrice1, Alan R. Prescott2 and Dario R. Alessi1 1University of Dundee, MRC Protein Phosphorylation Unit, James Black Centre and 2University of Dundee, Division of Cell Biology and Immunology, MSI/WTB complex, Dow Street, Dundee, DD1 5EH, Scotland, UK *Present address: Lund University, BMC, C11, S-22184 Lund, Sweden ‡Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 12 June 2006 Journal of Cell Science 119, 4059-4070 Published by The Company of Biologists 2006 doi:10.1242/jcs.03097 Summary Members of the PAR-1/MARK kinase family play critical membrane. We provide data indicating that the membrane roles in polarity and cell cycle control and are regulated by localisation of MARK3 required a highly conserved C- 14-3-3 scaffolding proteins, as well as the LKB1 tumour terminal domain, which has been termed kinase-associated suppressor kinase and atypical protein kinase C (PKC). domain-1 (KA-1). We also show that dissociation of 14-3-3 In this study, we initially investigated the mechanism from MARK3 did not affect catalytic activity, and that a underlying the interaction of mammalian MARK3 with MARK3 mutant, which could not interact with 14-3-3, was 14-3-3. We demonstrate that 14-3-3 binding to MARK3 normally active. Finally, we establish that there are is dependent on phosphorylation, and necessitates the significant differences in the subcellular localisation of phosphate-binding pocket of 14-3-3. -

A Role for LKB1 Gene in Human Cancer Beyond the Peutz–Jeghers Syndrome

Oncogene (2007) 26, 7825–7832 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW A role for LKB1 gene in human cancer beyond the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome M Sanchez-Cespedes Molecular Pathology Programme, Spanish National Cancer Centre (CNIO), Melchor Fernandez Almagro, Madrid, Spain Germline LKB1 mutations are responsible for Peutz– development, LKB1 expression becomes more pro- Jeghers syndrome (PJS). Tumors at several locations nounced in heart, esophagus, pancreas, kidney, colon, frequently arise in these patients, confirming that LKB1 is lung, small intestine and stomach (Luukko et al., 1999; linked to cancer predisposition and is therefore a bona fide Rowan et al., 2000). In adult tissues, levels of LKB1 tumor-suppressor gene. In humans, the LKB1 gene is protein are high in most epithelia, in the follicles and located in the short arm of chromosome 19, which is corpus luteum of the ovary, and the seminiferous tubules frequently deleted in many tumors of sporadic origin. of the testis, in myocytes from skeletal muscle and in glia However, LKB1 alterations in tumors other than those of cells (Rowan et al., 2000; Conde et al., 2007; Figure 1a). PJSare rarely reported. Notably, this is not the case for non-small-cell lung cancer, where nearly half of the tumors harbor somatic and homozygous inactivating mutations in LKB1. The present review considers the LKB1 and Peutz–Jeghers syndrome frequency and pattern of LKB1 gene mutations in LKB1 sporadic cancers of various origins, and the role of the Germline mutations of cause the autosomal encoded protein in cancer development. -

Protein Kinase Cζ Exhibits Constitutive Phosphorylation and Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-Triphosphate-Independent Regulation Irene S

Biochem. J. (2016) 473, 509–523 doi:10.1042/BJ20151013 509 Protein kinase Cζ exhibits constitutive phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate-independent regulation Irene S. Tobias*†, Manuel Kaulich‡, Peter K. Kim§, Nitya Simon*, Estela Jacinto§, Steven F. Dowdy‡, Charles C. King and Alexandra C. Newton*1 *Department of Pharmacology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, U.S.A. †Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, U.S.A. ‡Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, U.S.A. §Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Piscataway, NJ 08854, U.S.A. Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, U.S.A. Atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) isoenzymes are key modulators and insulin unresponsive, in marked contrast to the insulin- of insulin signalling, and their dysfunction correlates with insulin- dependent activation of Akt monitored by an Akt-specific reporter. resistant states in both mice and humans. Despite the engaged Nor does forced recruitment to phosphoinositides by fusing interest in the importance of aPKCs to type 2 diabetes, much the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of Akt to the kinase less is known about the molecular mechanisms that govern their domain of PKCζ alter either the phosphorylation or activity cellular functions than for the conventional and novel PKC of PKCζ . Thus, insulin stimulation does not activate PKCζ isoenzymes and the functionally-related protein kinase B (Akt) through the canonical phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate- family of kinases. -

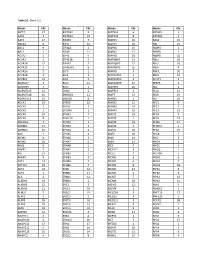

Table S1. Gene List Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr SEPT9

Table S1. Gene List Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr Genes Chr SEPT9 17 EIF2AK3 2 MAPK14 6 RASSF5 1 AAK1 2 EIF2AK4 15 MAPK15 8 RAVER2 1 AATK 17 EIF2B5 3 MAPK3 16 RAX2 19 ABCA1 9 EIF3J 15 MAPK4 18 RB1 13 ABL1 9 EIF4A2 3 MAPK6 15 RBBP4 1 ABL2 1 EIF4B 12 MAPK7 17 RBBP5 1 ACTR2 2 EIF4E 4 MAPK8 10 RBBP8 18 ACVR1 2 EIF4E1B 5 MAPK8IP1 11 RBL1 20 ACVR1B 12 EIF4E2 2 MAPK8IP2 22 RBL2 16 ACVR1C 2 EIF4EBP1 8 MAPK8IP3 16 RBPJ 4 ACVR2A 2 ELF3 1 MAPK9 5 RBPJL 20 ACVR2B 3 ELF4 X MAPKAPK2 1 RBX1 22 ACVRL1 12 ELK1 X MAPKAPK3 3 RCHY1 4 ADAM17 2 ELK3 12 MAPKAPK5 12 REEP5 5 ADAM29 4 ELK4 1 MAPRE1 20 REL 2 ADAMTS15 11 EML4 2 MAPRE3 2 RELA 11 ADAMTS18 16 ENDOD1 11 MAPT 17 RELB 19 ADAMTSL3 15 ENDOG 9 MARK1 1 RET 10 ADCK1 14 EP300 22 MARK2 11 RFC1 4 ADCK2 7 EPAS1 2 MARK3 14 RFC2 7 ADCK3 1 EPCAM 2 MARK4 19 RFC3 13 ADCK4 19 EPHA1 7 MAST1 19 RFC4 3 ADCK5 8 EPHA10 1 MAST2 1 RFC5 12 ADORA1 1 EPHA2 1 MAST3 19 RFNG 17 ADRBK1 11 EPHA3 3 MAST4 5 RFWD2 1 ADRBK2 22 EPHA4 2 MASTL 10 RFX2 19 AGK 7 EPHA5 4 MATK 19 RHEB 7 AIFM1 X EPHA6 3 MAX 14 RHO 3 AIFM2 10 EPHA7 6 MBIP 14 RHOA 3 AIM1 6 EPHA8 1 MCC 5 RHOC 1 AIMP2 7 EPHB1 3 MCF2L2 3 RHOQ 2 AIP 11 EPHB2 1 MCL1 1 RICTOR 5 AKAP4 X EPHB3 3 MCM2 3 RIOK1 6 AKT1 14 EPHB4 7 MCM3 6 RIOK2 5 AKT1S1 19 EPHB6 7 MCM4 8 RIOK3 18 AKT2 19 EPS8 12 MCM5 22 RIPK1 6 AKT3 1 ERBB2 17 MCM6 2 RIPK2 8 ALK 2 ERBB3 12 MCM7 7 RIPK3 14 ALKBH1 14 ERBB4 2 MCM8 20 RIPK4 21 ALKBH2 12 ERC2 3 MDM2 12 RMI1 9 ALKBH3 11 ERCC1 19 MDM4 1 RNASEL 1 ALMS1 2 ERCC2 19 MECOM 3 RNF213 17 ALPK1 4 ERCC3 2 MED12 X RNF220 1 ALPK2 18 ERCC4 16 MED12L 3 ROCK1 18 ALPK3 15 ERCC5 13