Review NOYO RIVER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of the Sixties: Art As an Agent for Change

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year Student Scholarship & Creative Works 2-27-2015 The pirS it of the Sixties: Art as an Agent for Change Kyle Anderson Dickinson College Aleksa D'Orsi Dickinson College Kimberly Drexler Dickinson College Lindsay Kearney Dickinson College Callie Marx Dickinson College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Elizabeth, et al. The Spirit of the Sixties: Art as an Agent for Change. Carlisle, Pa.: The rT out Gallery, Dickinson College, 2015. This Exhibition Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship & Creative Works at Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year by an authorized administrator of Dickinson Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Kyle Anderson, Aleksa D'Orsi, Kimberly Drexler, Lindsay Kearney, Callie Marx, Gillian Pinkham, Sebastian Zheng, Elizabeth Lee, and Trout Gallery This exhibition catalog is available at Dickinson Scholar: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work/21 THE SPIRIT OF THE SIXTIES Art as an Agent for Change THE SPIRIT OF THE SIXTIES Art as an Agent for Change February 27 – April 11, 2015 Curated by: Kyle Anderson Aleksa D’Orsi Kimberly Drexler Lindsay Kearney Callie Marx Gillian Pinkham Sebastian Zheng THE TROUT GALLERY • Dickinson College • Carlisle, Pennsylvania This publication was produced in part through the generous support of the Helen Trout Memorial Fund and the Ruth Trout Endowment at Dickinson College. -

Kuschel Jazz Vol.1 (2002)

Kuschel Jazz Vol.1 (2002) Written by bluesever Monday, 01 March 2010 18:07 - Last Updated Wednesday, 14 January 2015 12:03 Kuschel Jazz Vol.1 (2002) CD 1 01. Paul Desmond - Easy Living 02. Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World 03. Miles Davis & Gil Evans - Summertime (from Porgy & Bess) 04. Dave Brubeck - What Is This Thing Called Love 05. Astrud Gilberto with Stanley Turrentine - Solo El Fin (For All We Know) 06. Toots Thielemans - Bluesette 07. Coleman Hawkins - Autumn Leaves 08. Nat King Cole - These Foolish Things - Kuschel Jazz 09. Miles Davis - Round Midnight 10. Stan Getz - Misty 11. Tony Bennett - Quiet Nights Of Quiet Stars (Corcovado) 12. Gerry Mulligan - Blue Boy 13. Lionel Hampton with Reeds & Rhythm - Satin Doll 14. Dinah Washington - Mad About The Boy 15. Chet Baker - What?ll I Do 16. Duke Ellington & His Orchestra - Mood Indigo 17. Oscar Peterson - It Ain?t Necessarily So 18. Roy Hargrove Quintet - Everything I Have Is YoursDedicated To You CD 2 01. Paul Desmond - Wave 02. Antonio Carlos Jobim - Tereza My Love 03. Stan Getz - Forest Eyes 04. Mel Torme & Orchestra - Born To Be Blue 05. Ben Webster - Stardust 06. Ella Fitzgerald & Orchestra Buddy Bregman - Night And Day 07. Carmen McRae - Manha De Carnival (Where Did I Go) 08. Toots Thielemans - Quiet Evenings 09. Marcus Roberts - In A Mellow Tone 10. Arthur Prysock - At Last 11. Dave Brubeck Quartet - When You Wish Upon A Star 12. John Coltrane - Like Someone In Love 13. Chet Baker - She Was Too Good To Me 1 / 2 Kuschel Jazz Vol.1 (2002) Written by bluesever Monday, 01 March 2010 18:07 - Last Updated Wednesday, 14 January 2015 12:03 14. -

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami the Boy Named Crow "So You're All Set for Money, Then?"

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami The Boy Named Crow "So you're all set for money, then?" the boy named Crow asks in his typical sluggish voice. The kind of voice like when you've just woken up and your mouth still feels heavy and dull. But he's just pretending. He's totally awake. As always. I nod. "How much?" I review the numbers in my head. "Close to thirty-five hundred in cash, plus some money I can get from an ATM. I know it's not a lot, but it should be enough. For the time being." "Not bad," the boy named Crow says. "For the time being." I give him another nod. "I'm guessing this isn't Christmas money from Santa Claus." "Yeah, you're right," I reply. Crow smirks and looks around. "I imagine you've started by rifling drawers, am I right?" I don't say anything. He knows whose money we're talking about, so there's no need for any long-winded interrogations. He's just giving me a hard time. "No matter," Crow says. "You really need this money and you're going to get it--beg, borrow, or steal. It's your father's money, so who cares, right? Get your hands on that much and you should be able to make it. For the time being. But what's the plan after it's all gone? Money isn't like mushrooms in a forest--it doesn't just pop up on its own, you know. You'll need to eat, a place to sleep. -

The Sirens Call

1 Table of Contents pg. 03 - Thirty Minutes to Life | Sheree Shatsky pg. 93 - some mysteries are better unsolved | Linda M. Crate pg. 05 - Feed Your Demon | K.T. Tate pg. 94 - triton's melody | Linda M. Crate pg. 06 - Headache | Patrick J Wynn pg. 95 - Ghoul Days |David Berger pg. 07 - The Lighthouse at the End of the World | R.J. Meldrum pg. 96 - An Ensemble of Worms | Lee Andrew Forman pg. 11 - A Consuming Departure | JH Adams pg. 96 - The Rule | Patrick J Wynn pg. 13 - Gates of Hell | Mathias Jansson pg. 98 - Candy Girls | Mandy McHugh pg. 14 - Misplaced Trust | Micah Castle pg. 101 - Graveyard Shift | David Lewis Pogson pg. 16 - The Swimming Pool | Alex Woolf pg. 102 - The Fireworks Wars | Cecilia Kennedy pg. 19 - Snap Alley | Martin P. Fuller pg. 104 - Harsh Weather | Rickey Rivers Jr. pg. 21 - The Grasping Darkness | J.W. Grace pg. 106 - Kafkau Lait | Phillip T. Stephens pg. 22 - Try the Fries | Ken Goldman pg. 109 - Scurry | Lesley-Ann Campbell pg. 23 - The Hive | Erin Sweet Al-Mehairi pg. 110 - The Demons’ Symphony | Josie Dorans pg. 25 - Toothpick | Justin Joseph pg. 112 - The Untrodden Path | Linda Lee Rice pg. 26 - Ongoing Screams | Olivia Arieti pg. 112 - She Who Is Not Me | Linda Lee Rice pg. 27 - A Squeal of Fortune | Melissa R. Mendelson pg. 113 - Eternal Promise | Dusty Davis pg. 29 - The Cursed Crave Silence | J. Rohr pg. 115 - Requiem of Loneliness | Gregory L. Steighner pg. 30 - Night Terror | Terry Miller pg. 119 - Punishment | Scott Blanke pg. 32 - Wyrm | Jeffrey Durkin pg. -

Jazz Enciclopedia

John Abercrombie Джон Эберкромби Родился: 16 декабря 1944 в Порт Честере,штат Нью-Йорк Удивительное умение Джона Эберкромби сочетать в своем творче- стве многообразие джазовых направлений сделало его одним из самых влиятельных акустических и электро гитаристов 70-х и начала 80-х годов. Записи Эберкромби на ECM помогли этому рекорд лейблу обрести свою уникальную нишу в продвижении прогрессивного камерного джаза. В по- следнее время свет его звезды несколько угас - этому есть свои причины. Его излишняя дань консерватизму доминирует над джазом, но Эберкромби по-прежнему остается гранд-персоной с высокой творческой энергетикой. Есть понятие "стиля Эберкромби": он основан исключительно на джазе и содержит в себе весь арсенал современной импровизационной музыки. Но главное - он всегда подразумевает и демонст- рирует нечто большее, чем могут вместить все диапазоны музыки - от фолка и рока до Вос- точной и Западной классической музыки. С 1962 по 1966 год Эберкромби учился в Бостон- ском музыкальном колледже (Berklee College of Music), и во время учебы гастролировал с блюзменом Джонни Хэммондом (Johnny Hammond). В 1969 году Эберкромби переезжает в Нью-Йорк и некоторое время играет в группах, возглавляемых барабанщиками Чико Хамиль- тоном и Билли Кобэмом. Группа, в которой он впервые обратил на себя внимание, называлась "Spectrum", а первый альбом, где Эберкромби заявил о себе как бэнд-лидер, назывался "Timeless. Альбом был записан с барабанщи- ком Джеком ДеДжонетте и клавишником Яном Хаммером. Затем последовал "Gateway" в со- ставе другого трио с Джеком ДеДжонетте и ба- систом Дэйвом Холландом, заменившим Яна Хаммера. Тонкий и проникновенный стиль Эберкромби дает наибольший эффект в малых формах: в составе Gateway трио, или в дуэте с гитаристом Ральфом Таунером. -

Dec 2012.Qxd

GLOBAL TIGER FORUM IS AN INTER-GOVERNMENTAL INTERNATIONAL BODY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TIGER IN THE WILD G L O B A L T I G E R F O R U M GTFNEWS DECEMBER 2012 GTF IS NOW ON TWITTER & FACEBOOK - FOLLOW US www.twitter.com/Unitedfortigers www.facebook.com/Globaltigerforum PAYMENT/DONATION TO GLOBAL TIGER FORUM The payment/donation to the Global Tiger Forum may be made though an Account Payee Cheque or Demand Draft in favour of "Global Tiger Forum" at New Delhi OR Please transfer the amount to HSBC BANK NEW YORK (MRMDUS33) CHIPS ABA 0108, FEDWIRE ROUTING NO. 021001088 FOR CREDIT TO MAHBINBBCPN (A/C No. 000038245) OF BANK OF MAHARASHTRA FOR ULTIMATE CREDIT TO A/C No. 00000020072263547 OF THE GLOBAL TIGER FORUM MAINTAINED WITH BANK OF MAHARASHTRA, UPSC BRANCH , NEW DELHI ,INDIA. GRANT/DONATION TO THE GLOBAL TIGER FORUM WITHIN INDIA IS TAX EXEMPTED UNDER SECTION 80G OF THE INCOME TAX ACT. COVER AND TIGER PHOTOGRAPHS BY ADITYA SINGH / ART - ANANDA BANERJEE GLOBAL TIGER FORUM GLOBAL TIGER FORUM IS AN INTER-GOVERNMENTAL INTERNATIONAL BODY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF TIGER IN THE WILD GTFNEWS DECEMBER 2012 Edited by S P YADAV Global Tiger Forum Secretariat D-87, Lower Ground Floor, Amar Colony, Raghunath Mandir Road, Lajat Nagar IV New Delhi 110024 GTFNEWS IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII CONTENTS Note from the Secretary General (05) Have we turned the corner in Tiger Conservation? (06) 2nd Asia Ministerial -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Unchained Manhood The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Unchained Manhood The Performance of Black Manhood During the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction Eras A dissertation submitted in satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Mark Asami Okuhata 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Unchained Manhood The Performance of Black Manhood During the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction Eras by Mark Asami Okuhata Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Brenda Stevenson, Chair My dissertation examines the ways in which formerly enslaved black men constructed their gender identities. According to the cultural logic of the nineteenth century, black men were emasculated subjects who were rendered “boys” by the slave regime. However, I argue that former male slaves parlayed the cultural conditions of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction Eras into performative demonstrations of their manhood. My first chapter is an introduction to the intersectional study of black manhood. By delineating a historiography of the gender concept, I argue that the study of black men as gendered subjects demands scholarly attention. My second chapter centers on black soldiers during the Civil War. By handling, parading, and ii discharging firearms, I argue that armed black men signified a stark break from the Colonial and antebellum periods. By the war’s end, I argue that the demilitarization of the Union Army, and the end of Reconstruction precluded black men from employing firearms as a means of constructing their black manly identity. My third chapter investigates the ways in which slavery and the Civil War impinged upon the bodies of black men during the postwar. -

Alfred Hitchcock's Ghostly Gallery

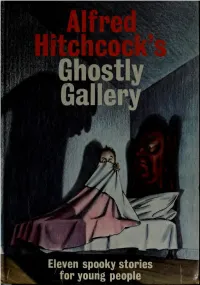

I M 1 ostl GaHer wen spooky stories for youiig people :?«3fev . ' '- <m. ! Alfred Hitchcock's Ghostly Gallery "This is a book of ghost stories," says Alfred Hitch- cock in his introduction, "and is designed both to frighten and instruct." Mr. Hitchcock has selected stories by nine fa- mous ghost writers to prove his point. To see if he succeeds, read on Alfred Hitchcock's 1 f*\ jj lustrated by Fred Banbery Random House New York © Copyright, 1962, by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in New York by Random House, Inc., and simultaneously in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada, Limited. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 62-14298 Manufactured in the United States of America The editor gratefully acknowledges the invaluable assistance of Robert Arthur in the preparation of this volume and thanks the following for permission to include copyrighted material: A. P. Watt & Son and the executors of the Estate of the late H. G. Wells for "The Truth About Pyecraft," from Short Stories of H. G. Wells; Brandt & Brandt for "Miss Emmeline Takes Off" by Walter R. Brooks, first published in The Saturday Evening Post, Copyright, 1945, by The Curtis Publishing Company; Robert Arthur for "The Haunted Trailer," Copy- right, 1941, by Weird Tales under the original title of "Death Thumbs A Ride," Robert Arthur and Popular Publications, Inc. for "The Wonderful Day," Copy- right, 1940, as "Miracle on Main Street" by Popular Publications, Inc. and "Ob- stinate Uncle Otis," Copyright, 1941, by Popular Publications; Harold Matson Company for "Housing Problem" by Henry Kuttner, Copyright, 1944, by Street and Smith and reprinted from Charm Magazine; Arkham House for "In A Dim Room" from The Fourth Book of Jorkens, Copyright, 1948, by Lord Dunsany; Stephen Aske, literary agent, for "The Waxwork" by A. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

H ILL I NOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. THE BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS JANUARY 1991 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 5 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS EXPLANATION OF CODE SYMBOLS USED WITH ANNOTATIONS * Asterisks denote books of special distinction. R Recommended. Ad Additional book of acceptable quality for collections needing more material in the area. M Marginal book that is so slight in content or has so many weaknesses in style or format that it should be given careful consideration before purchase. NR Not recommended. SpC Subject matter or treatment will tend to limit the book to specialized collections. SpR A book that will have appeal for the unusual reader only. Recommended for the special few who will read it. C.U. Curricular Use. D.V. Developmental Values. * ** THE BULLETIN OF THE CENTER FOR CHILDREN'S BOOKS (ISSN 0008-9036) is published monthly except August by The University of Chicago Press, 5720 S. Woodlawn, Chicago, Ilinois, 60637, for The Center for Children's Books. Betsy Hearne, Editor; Roger Sutton, Senior Editor; Zena Sutherland, Associate Editor; Deborah Stevenson, Editorial Assistant. An advisory committee meets weekly to discuss books and reviews. The members are Alba Endicott, Robert Strang, Elizabeth Taylor, Kathryn Pierson, Ruth Ann Smith, and Deborah Stevenson. Reviewers' initials are appended to reviews. SUBSCRIPTIoN RATES: 1 year, $24.00; $16.00 per year for two or more subscriptions to the same address; $15.00, student rate; in countries other than the United States, add $3.00 per subscription for postage. -

![Filibuster 2011: the Director’S Cut, at ] 52 53 Life Is Full of Shit 人生充满狗屎 to the Absence of a Throne 缺失的宝座 Mekoi Scott Joseph S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9822/filibuster-2011-the-director-s-cut-at-52-53-life-is-full-of-shit-to-the-absence-of-a-throne-mekoi-scott-joseph-s-10789822.webp)

Filibuster 2011: the Director’S Cut, at ] 52 53 Life Is Full of Shit 人生充满狗屎 to the Absence of a Throne 缺失的宝座 Mekoi Scott Joseph S

This river is the color red; it flows into the sea. Two lives become one thought— it is the restless mind. 这是一条红色的河 它流入大海 两个人的生命成为一个思绪 为不安的心灵 FILIBUSTER 阻挠议事 2011 高寿 Writings whose words vividly paint pictures Context 1 Kali Piro Origins, Pt. 2 58 Joseph S. Brannon Porphyria’s Song 4 Stephen Paul Bray Capital Idea 59 Alicia Fry Little Bird 6 Rachel Meeks I Do Declare, a Six-Word Memoir 61 Catherine Bailey Origins, Pt. 1 10 Joseph S. Brannon Private Language 62 Robert Bullard Heart’s Raining Reign 11 Kali Piro Mighty Mini Axolotl 63 April Fredericks “like an old vinyl record….” 12 Meggy-Kate Gutermuth Untitled 64 Matthew K. Kemp Beagle Serenade 14 Kevin Lee Garner Read It 66 Amie Seidman et. al. The Old Place 16 Kali Piro Midnight Seraphs 69 Roya S. Hill Swans Trained 18 E. D. Woodworth Harold’s Star 70 Kevin Lee Garner The Fog Puncher 19 Arvilla Fee Dive 78 Andrea VanderMey Alone 20 Audra Hagel Fish in a Tank 79 Antonio Byrd The Graveyard Tale 22 Lacey Young A Night’s Terror 85 Kali Piro A Wandering Soul 27 Jacob Lambert Bandages on Her Neck 86 Sarah Fredericks Unforgiveness 28 Kevin Lee Garner Reflections in Passage 90 Arvilla Fee Scientific Analysis of Academic Mold 32 Sarah Fredericks (Extra) Ordinary 93 Miranda Hale-Phillips A Six-Word Memoir 34 Catherine Bailey Christmas Bankruptcy 94 Alexander Bruce Herbitter Letting Go 35 Rachel Meeks Blue Topaz 96 Kali Piro To a Leaf 39 Stephen Paul Bray A Wanderer’s Elegy 97 Kevin Lee Garner The Life of a Chevy Nova 40 Matthew Johnson An Antisocial Squirrel 98 Audra Hagel The Secret Page 42 Kali Piro Exchanges of the Heart 100 Kali Piro The Pocketwatch 51 Justin Foster Falling Stars 103 Sarah Fredericks Life is Full of Shit 52 MeKoi Scott This is Living 104 Arvilla Fee Halt 52 Alicia Fry Academic Apocalypse 106 Steven Parker To the Absence of a Throne 53 Joseph S. -

In the Middle: North of 45 Susan A

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2012 In the Middle: North of 45 Susan A. Morgan Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Morgan, Susan A., "In the Middle: North of 45" (2012). All NMU Master's Theses. 469. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/469 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. IN THE MIDDLE: NORTH OF 45 By Susan A. Morgan THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Graduate Studies Office 2012 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM IN THE MIDDLE: NORTH OF 45 This thesis by Susan A. Morgan is recommended for approval by the student’s thesis committee in the Department of English and by the Dean of Graduate Studies. __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chair: Dr. Paul Lehmberg Date __________________________________________________________________ First Reader: Matthew Gavin-Frank Date __________________________________________________________________ Second Reader: Dr. Robert Whalen Date __________________________________________________________________ Department Head: Dr. Raymond Ventre Date __________________________________________________________________ Assistant Provost, Dean of Graduate Studies and Research: Date Dr. Brian Cherry OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from others with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. -

The Opiate: Fall 2016, Vol. 7

TheThe OpiateOpiate Fall Fall2016, Vol. 2016, 7 Vol. 7 This page intentionally left blank YourThe literary dose.Opiate © The Opiate 2016 This magazine, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission. Cover art: Carrie Cottini 3. The Opiate, Fall Vol. 7 Editor-in-Chief Genna Rivieccio Editorial Advisor Armando Jaramillo Garcia “Is there no way out of Contributing Writers Fiction: Shay Siegel 10 Joel Streicker 16 the mind?” Jo Mortimer 23 Daniel Ryan Adler 26 Evelyn Sharenov 31 -Sylvia Plath John M. Keller 37 Poetry: John Gosslee 42 A.G. Price 43 Joseph Harms 46 Jackie Sherbow 48 Chris Campanioni 49 Kailey Tedesco 51 Criticism: Genna Rivieccio 54 4. 5. The Opiate, Fall Vol. 7 deceased father (and, by association, her) for causing the faultiness of a generator at Editor’s Note the nearby fairground. Some people with an overly literal mind might question: “Genna, why lipsticks for the Next is Daniel Ryan Adler’s seventh chapter from Sebastian’s Babylon, rife with coffee fall cover? What does makeup have to do with fiction and poetry?” Well, more than shop brawls and dragon slaying reimaginings. Hurt feelings and misappropriated you might think, as it were. But before we get to that, let me break it down for you emotions are, naturally, par for the course as Sebastian gradually accepts that Lexi is simply: the lips of writers are often sealed, reserved for opening only when bringing repulsed by and uninterested in him. the glass or bottle to them. And nothing cinches a closed mouth like a daub of lipstick.