Issue Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burkina Faso)

Caractérisation et modélisation des nappes d’eau souterraine au voisinage de petites retenues d'eau d'irrigation en zone de socle : cas de Kierma et de Mogtédo (Burkina Faso) Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur en sciences de l'ingénieur Par Apolline BAMBARA Thèse défendue le 25 février 2021 devant le jury composé : Prof. Alain DASSARGUES, Université de Liège (Belgique) – Président Dr. Serge BROUYÈRE, Université de Liège (Belgique) – Promoteur Dr. Philippe ORBAN, Université de Liège (Belgique) – membre Dr. Benjamin DEWAL, Université de Liège (Belgique) – membre Dr. Eric HALLOT, Institut Scientifique de Service Public (Belgique) – membre Dr. Florence HABETS, Ecole Normale Supérieure (France) – membre Prof. René THERRIEN, Université Laval (Canada) – membre Dr. Youssouf KOUSSOUBÉ, Université Joseph Ki-Zerbo (Burkina Faso) – membre Année académique 2020-2021 Avec l’appui de : Je dédie chaleureusement cette thèse à : Ma chère amie Samira Ouermi, décédée le 18 juin 2020 en attente de la soutenance de sa thèse de doctorat, Mon défunt père G. Aristide, Ma chère fille Haoua Charlène Sangaré, Ma mère Pascaline Compaoré, Ma chère amie Lucette Degré, « C’est quand le puits est sec que l’eau devient une richesse » Proverbe français Résumé Les petites retenues d’eau ont été massivement construites en Afrique subsaharienne pour disposer de sources alternatives d’eau pour l’irrigation et l’abreuvement du bétail en période de sécheresse. Elles contribuent au développement socio-économique et à la sécurité alimentaire des populations à travers la pratique de l’agriculture irriguée en saison sèche. Malheureusement, ces retenues d’eau ont tendance à s'assécher prématurément avant les dernières récoltes. -

Membres Panthers Card 2019

MEMBRES PANTHERS CARD 2019 Nom de l'entreprise Adresse Promotion proposée par l'entreprise ALPES BATTERIE 73 Route du Crêt Gojon, 74200 Margencel 10% de remise sur tous les articles en magasin hors promotions AMAZING BEAUTE 7 Place du Marché, 74200 Thonon-les-Bains -10% sur toutes les prestations hors cures, forfaits et cartes cadeaux. AUTODISTRIBUTION 20 Avenue Pré Robert N, 74200 Anthy-sur-Léman -50% sur Disques de freins ; -50% sur Plaquettes de freins ; -35% sur les Filtres ; Conditions en magasin AUTOVERIF 289A Route des Blaves, 74200 Allinges remise 10% sur contrôle technique BELL' Institut 71 Grande Rue - 74200 THONON -10% sur présentation de la Panthers Card. BISTROT LE COUSIN MICHEL 3 Rue des Italiens, 74200 Thonon-les-Bains KIR ou Café offert pour l'achat d'un repas. BOUTIQUE FERRARI 88 Avenue de Bonnatrait, 74140 Sciez -30% sur tous les articles en boutique hors promotions et soldes. BRASSERIE DU BELVEDERE 1B Avenue du Léman, 74200 Thonon-les-Bains Café offert sur présentation de la carte BUFFALO GRILL 219, Route du Crêt Gojon, Route Nationale 5, 74200 Margencel 1 Apéritif offert par personne (1 Kir, 1 pétillant du Shérif ou 1 Cocktail MIAMI) pour l'achat d'un repas. BUT Boulevard du Pré Biollat, 74200 Anthy-sur-Léman -10% sur les produits de décoration et ameublement. 5% de réduction pour tout voyage réservé chez un partenaire Carrefour Voyages ; 7% de réduction sur les CARREFOUR VOYAGES 2 Rue des Italiens, 74200 Thonon-les-Bain voyagesVOYAMAR et HELIADES (Hors taxes Aéroport et hors Promotions) CARROSSERIE DU CANAL 8 Route de la Visitation, 74200 Thonon-les-Bains remis 20% sur la main d'oeuvre hors assurance Cave de la Bonne Rencontre 64 Avenue d'Evian - 74200 THONON -10 à -12% sur vins champagne et bibtainers au détail. -

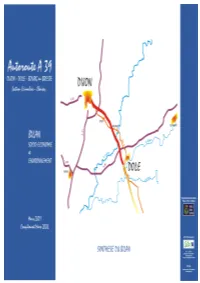

Synthèse Du Bilan (Dijon

1 8. Sylviculture ..........................................................................................................26 Sommaire 9. Urbanisme ...........................................................................................................27 10. Bruit.......................................................................................................................28 11. Patrimoine...........................................................................................................29 12. Paysage...............................................................................................................29 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 3 13. Emprunts-Dépôts................................................................................................31 CONCLUSIONS....................................................................................33 I – UN BILAN : DES EFFETS ATTENDUS, DES EFFETS CONSTATÉS.......... 6 II – A39 DIJON DOLE : MAILLON D’UN RÉSEAU AUTOROUTIER DENSE............ 7 III – UNE ZONE D’ÉTUDE SOUS INFLUENCE DIJONNAISE.................... 9 IV – LE BILAN DES EFFETS DE L’AUTOROUTE A39 DIJON-DOLE SUR LA SOCIO-ÉCONOMIE ET LES TRANSPORTS..................................... 10 1. Les effets de la construction sur l’économie régionale............................. 10 2. Les effets sur les transports............................................................................... 11 3. Phase d’exploitation : des ressources fiscales, -

Annexe-5 Notes Techniques A-70

ANNEXE-5 NOTES TECHNIQUES A-70 A-71 A-72 A-73 A-74 A-75 A-76 A-77 A-78 A-79 A-80 ANNEXE-6 DOSSIER DU PROGRAMME D’ANIMATION ET DE SENSIBILISATION 1. Raisons pour la réalisation des activités d’animation et de sensibilisation Nous avons constaté des problèmes suivants concernant la gestion et la maintenance des installations d’approvisionnement en eau potable dans les zones de cible. La gestion est différente suivant les forages et beaucoup de CPEs ne fonctionnent pas. Il manque des maintenances quotidiennes. Il existe des concurrences entre le système d’AEPS et des forages équipés de PMH dans un village et l’AEPS n’arrive pas à vendre suffisamment d’eau pour qu’il soit rentable. Les usagers ne rendent pas comte des problèmes sur la gestion actuelle des installations d’approvisionnement en eau potable Les communes ne possèdent pas de compétences sur la gestion et la maintenance des installations d’approvisionnement en eau potable de façon quantitative et qualitative. Nous allons réaliser des formations dans le Programme d’animation et de sensibilisation pour résoudre ces problèmes. L’aperçu des activités est le suivant : ① Activités d’animation et de sensibilisations pour les forages équipés de PMH ¾ Reconnaissance du Projet et du système de réforme pour la gestion d’approvisionnement en eau potable (ci-après, « le système de réforme ») à l’échelle communale ¾ Préparation des manuels et du matériel audio-visuel ¾ Atelier pour la sensibilisation des villageois, établissement du CPE par des réunions villageoises. ¾ Formation auprès des personnes chargées d’hygiène et de trésorier du CPE ¾ Formation auprès d’AR ¾ Suivi/appui de gestion ② Activités d’animation et de sensibilisation pour le système AEPS ¾ Reconnaissance du Projet et du système de réforme pour la gestion d’approvisionnement en eau potable (ci-après, « le système de réforme ») à l’échelle communale ¾ Préparation des manuels et du matériel audio-visuel ¾ Atelier pour la sensibilisation des villageois, établissement de l’AUE par des réunions villageoises. -

Ceni - Burkina Faso

CENI - BURKINA FASO ELECTIONS MUNICIPALES DU 22/05/2016 STATISTIQUES DES BUREAUX DE VOTE PAR COMMUNES \ ARRONDISSEMENTS LISTE DEFINITIVE CENI 22/05/2016 REGION : BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN PROVINCE : BALE COMMUNE : BAGASSI Secteur/Village Emplacement Bureau de vote Inscrits ASSIO ASSIO II\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 355 BADIE ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 243 BAGASSI ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 440 BAGASSI ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 403 BAGASSI TINIEYIO\ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 204 BAGASSI TINIEYIO\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 439 BANDIO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 331 BANOU ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 320 BASSOUAN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 252 BOUNOU ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 358 BOUNOU ECOLE2\ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 331 DOUSSI ECOLE B Bureau de vote 1 376 HAHO CENTRE\CENTRE ALPHABETISATION Bureau de vote 1 217 KAHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 395 KAHO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 349 KANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 323 KAYIO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 303 KOUSSARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 419 MANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 458 MANA ECOLE Bureau de vote 2 451 MANZOULE MANZOULE\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 166 MOKO HANGAR Bureau de vote 1 395 NIAGA NIAGA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 198 NIAKONGO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 357 OUANGA OUANGA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 164 PAHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 378 SAYARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 465 SIPOHIN ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 324 SOKOURA ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 184 VY ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 534 VY ECOLE2\ECOLE1 Bureau de vote 1 453 VYRWA VIRWA\ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 141 YARO ECOLE Bureau de vote 1 481 Nombre de bureaux de la commune 33 Nombre d'inscrits de la commune 11 207 CENI/ Liste provisoire -

Etablissements Post-Primaires Et Secondaires Prives Reconnus

ETABLISSEMENTS POST-PRIMAIRES ET SECONDAIRES PRIVES RECONNUS N° REGION ETABLISSEMENTS PROVINCES COMMUNES SECTEUR/VILLE 1 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE L’EXPERIENCE BAZEGA DOULOUGOU LAMZOUDO 2 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE DU COMPLEXE SCOLAIRE PRIVE ALPHA OMEGA BAZEGA TOECE TOECE 3 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE EVANGELIQUE RAYI-ZALLEM BAZEGA SAPONE SAPONE 4 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE LA FRATERNITE DE KOMBISSIRI BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI KOMBISSIRI 5 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE LA SOLIDARITE DE KOMBISSIRI BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI KOMBISSIRI 6 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE LA VOIE DU SUCCES BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI KOMBISSIRI 7 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE LES PATRIOTE DE KAYAO BAZEGA KAYAO BASSAM 8 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE L'EVEIL DE DOUMDOUNIE BAZEGA DOUMDOUNI DOUMDOUNI 9 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE NABYOURE BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI SECTEUR 5 10 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE WINDYAAM DE KOULPELE BAZEGA KOULPELE KOULPELE 11 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE YAM WEKRE DE TIM-TIM BAZEGA KAYAO TIM-TIM 12 CENTRE SUD COLLEGE PRIVE YENNENGA DE KOMBISSIRI BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI SECTEUR 3 LYCEE PRIVE BANGRE NOOMA DE GOUMSIN Ex COLLEGE PRIVE 13 CENTRE SUD BANGRE NOOMA BAZEGA KAYAO GOUMSI 14 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE BOBLAWENDE BAZEGA DOULOUGOU KAGAMZINCE 15 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE DU GROUPE SCOALIRE SAINT ANATOLE DE NORYIDA BAZEGA NOBERE NORYIDA 16 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE MANEGBA DE KOMBISSIRI BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI KOMBISSIRI 17 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE SABILOUL HOUDA DE KOASSA BAZEGA KOMBISSIRI KOASSA 18 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE VIVE LE PAYSAN BAZEGA SAPONE SECTEUR 1 19 CENTRE SUD LYCEE PRIVE MANEGD-ZANGA DE SAPONE BAZEGA SAPONE SECTEUR -

Quality of Care and Client Willingness to Pay for Family Planning Services at Marie Stopes International in Burkina Faso

Population Council Knowledge Commons Reproductive Health Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2013 Quality of care and client willingness to pay for family planning services at Marie Stopes International in Burkina Faso Placide Tapsoba Population Council Dalomi Bahan Emily Forsyth Queen Gisele Kaboré Population Council Sally Hughes Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, Maternal and Child Health Commons, Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons, and the Women's Health Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Tapsoba, Placide, Dalomi Bahan, Emily Forsyth Queen, Gisele Kaboré, and Sally Hughes. 2013. "Quality of care and client willingness to pay for family planning services at Marie Stopes International in Burkina Faso." Ouagadougou: Population Council. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. Quality of care and client willingness to pay for family planning services at Marie Stopes International in Burkina Faso Authors: Placide Tapsoba, Dalomi Bahan, Emily Forsyth Queen, Gisèle Kaboré, Sally Hughes i Authors and acknowledgements Acronyms EPI Info A public domain statistical software for NGO Non governmental organisation epidemiology SPSS Statistical Package for the Social FCFA Franc de la Communauté Financière Sciences d’Afrique (West African CFA Franc)1 SRH Sexual and reproductive health FP Family planning USAID United States Agency for International IUD Intrauterine device Development LAPM Long-acting and permanent method WTP Willingness to pay MSI Marie Stopes International Acknowledgements The Population Council would like to thank all the organisations and individuals who contributed to the success of this study. -

Burkina Faso Ministère De L'eau Et De L'assainissement Direction Générale

Burkina Faso Ministère de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement Direction Générale de l’Eau Potable Projet de Renforcement de la Gestion des Infrastructures Hydrauliques de l’Approvisionnement en Eau Potable et de Promotion de l’Hygiène et de l’Assainissement en milieu rural Phase II (PROGEA II) RAPPORT FINAL Avril 2020 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) Earth and Human Corporation Japan Techno Co.,Ltd. GE JR 20-032 Photos de la mise en œuvre des activités du projet (1) Atelier-Bilan sur la mise en œuvre de la Réforme Atelier national de validation et de réflexion sur la mise en (12 au 15 Janvier 2016) œuvre de la Réforme (23 au 24 Mars 2016) Travaux de la relecture du document cadre et des outils de la Etude de Base (Village de Wanonghin, Commune de Laye, Réforme par un comité technique Province du Kourwéogo, Région du Plateau Central, 01 (21 Août au 16 Septembre 2017, Koudougou) Février 2016) Session de formation des communes de la région du Centre- Atelier régional sur la Réforme dans la région du Centre-Sud (08 au Sud sur la Réforme 09 Décembre 2017 à Manga) (23 Février 2017 à Kombissiri) i Photos de la mise en œuvre des activités du projet (2) Suivi des activités de la commune de la région du Centre-Sud Formation des maintenanciers sur la mise en œuvre de la Réforme (21 Mars 2018, Kombissiri) (26 Avril 2017 à la commune de Toécé, province du Bazéga) Formation des maintenanciers de la région du Centre-Sud sur Formation de l’association des maintenanciers l’entretien des PMH de la région du Centre-Sud (26 Avril 2017 à la -

4-Liste Des Forages Non Encore Équipés De Pompe En 2017

4_Liste de tous les forages non encore équipés de pompe REGION PROVINCE COMMUNE Village BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BADIE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BAGASSI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI BANOU BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI KAHO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI KAYIO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI MANA BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI MOKO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI MOKO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BAGASSI VIRWE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BOROMO BOROMO-SECTEUR 2 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BOROMO BOROMO-SECTEUR 2 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BOROMO KOHO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE BOROMO OUROUBONO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE FARA BOUZOUROU BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE FARA PIA BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE FARA TONE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE OURY SANI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE OURY ZINAKONGO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE PA DIDIE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE PA DIDIE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE PA KOPOI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE PA PA BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI BATTITI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI PANA BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI PANI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI POMPOI BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI POMPOI-GARE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE POMPOI SAN BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE SIBY BALLAO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE SIBY SIBY BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE YAHO BONDO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE YAHO BONDO BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE YAHO GRAND-BALE BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN BALE YAHO MADOU BOUCLE DU -

Fasi-Paejf-Centre-Sud

MINISTERE DE LA JEUNESSE, DE LA FORMATION BURKINA FASO ET DE L'INSERTION PROFESSIONNELLES -------------- -------------------- Unité - Progrès - Justice SECRETARIAT GENERAL -------------------- FONDS D'APPUI AU SECTEUR INFORMEL -------------------- LISTE DES BENEFICIAIRES DU PROGRAMME D'AUTONOMISATION ECONOMIQUE DES JEUNES ET DES FEMMES REGION DU CENTRE SUD N° DU CONTACT SECTEUR MONTANT RANG NOM ET PRENOM(S) N° CNIB SEXE LOCALISATION PROVINCE REGION DOSSIER TEL D'ACTIVITE ACCORDE FASI/PAE1 - Artisanat de 1 ZONGO BOUREIMA 68043804 B3450113 M NOBERE Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 500 000 15373 service FASI/PAE1- 2 TONDE Lucienne 74669776 B2558196 F Commerce Secteur 3, Manga Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 250 000 2911 FASI/PAE1- 3 ZOUNGRANA Sambila 76543731 B4499871 M Agropastoral Secteur 03, Manga Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 1 000 000 2979 FASI/PAE1 - 4 KABRE TALATO 76333254 B6068229 F Agropastoral SECT 30 Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 1 000 000 15805 FASI/PAE1- secteur 5 COMPAORE Fatoumata 68000297 B3179491 M Agropastoral Bazèga Centre-Sud 250 000 1486 2,KOMBISSIRI FASI/PAE1- 6 KABRE Moussa 78291447 B1062339 M Agropastoral Saponé Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 1 000 000 2776 FASI/PAE1- TIENDREBEOGO Yembi 7 79558217 B6422515 M Agropastoral Koussaba- Toécé Bazèga Centre-Sud 500 000 2807 Issa FASI/PAE1- 8 NACOULMA Marata 57221069 B5668421 F Commerce MANGA Zoundwéogo Centre-Sud 200 000 2874 FASI/PAE1- 9 COMPAORE Saïdou 78329830 B2774628 M Agropastoral Secteur 1, Kombissiri Bazèga Centre-Sud 800 000 2953 FASI/PAE1- 10 BALORA Bassido Oscar 78066489 B0349750 M Agropastoral SECTEUR 07, -

Ii-3- Liste Nominative Des Etablissements Post-Primaires Et Secondaires D'enseignement General Prives Reconnus

II-3- LISTE NOMINATIVE DES ETABLISSEMENTS POST-PRIMAIRES ET SECONDAIRES D'ENSEIGNEMENT GENERAL PRIVES RECONNUS N° REGION NOM DE L'ETABLISSEMENT PROVINCES COMMUNES SECTEUR/VILLE 1 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE COULIBALY AMADOUBA BANWA SOLENZO SOLENZO 2 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE DE BENA BANWA BENA BENA 3 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE DOFINIHANMOU BANWA BENA BENA 4 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE DOFINITA DE DABOURA BANWA SOLENZO DABOURA 5 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE DOMINIQUE SYANO KONATE BANWA SOLENZO SOLENZO 6 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE EVANGELIQUE LA RESTAURATION BANWA SOLENZO SOLENZO 7 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE EVANGELIQUE SION BANWA SOLENZO SECTEUR 4 8 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE GRACE DIVINE BANWA SANABA SANABA 9 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE LABARAKA DE DIRA BANWA SOLENZO DIRA 10 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE LANAYA DE SANABA BANWA SANABA SANABA 11 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE LE SOLEIL LEVANT BANWA TANSILA TANSILA 12 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE MODERNE LES PROFESSIONNELS BANWA SOLENZO SECTEUR 2 13 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE SAINTE EDWIGE DE TOUGAN BANWA BENA BENA 14 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE SOL BENI BANWA SOLENZO SOLENZO 15 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN LYCEE PRIVE ARC-EN-CIEL BANWA KOUKA SECTEUR 1 16 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN LYCEE PRIVE CATHOLIQUEBERACA SCHOOL NOTRE DAME DE BANWA SOLENZO SECTEUR 3 17 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN LYCEESOLENZO PRIVE EZER DE KOUKA Ex LYCEE PRIVE BANWA SOLENZO SOLENZO 18 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN KESSEL DE KOUKA BANWA KOUKA SECTEUR 5 19 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN LYCEE PRIVE WIOLOHO BANWA BONDOUKUI BONDOUKUI 20 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE ANSELME TITIAMA SANOU BANWA TANSILA TANSILA 21 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE ADEODAT KOSSI NOUNA SECT 3 22 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE CHARLES LWANGA KOSSI NOUNA SECT 3 23 BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN COLLEGE PRIVE FRANCO-ARABEEVANGELIQUE CANAAN KADIDJATOU DE KOSSI DJIBASSO SECT. -

Secretariat General ---Direction D

MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE BURKINA FASO ET DE L’ALPHABETISATION ------------ ---------------- Unité - Progrès - Justice SECRETARIAT GENERAL ---------------- DIRECTION DE L’INFORMATION, DE L’ORIENTATION SCOLAIRE, PROFESSIONNELLE ET DES BOURSES Arrêté n°2018-__________/MENA/SG/DIOSPB portant proclamation de la liste des élèves du post primaire bénéficiaires de la bourse scolaire au titre de l’année scolaire 2017-2018 ============================= LE MINISTRE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE ET DE L’ALPHABETISATION, Vu la Constitution ; Vu le décret n° 2016-001/PRES du 6 janvier 2016 portant nomination du Premier Ministre ; Vu le décret n° 2018-0035 /PRES/PM du 31 janvier 2018 portant remaniement du Gouvernement ; Vu le décret n°2017-0148/PRES/PM/SGG-CM du 23 mars 2017 portant attributions des membres du Gouvernement ; Vu le décret n° 2017-0039/PRES/PM/MENA du 27 janvier 2017 portant organisation du Ministère de l’Education nationale et de l’Alphabétisation ; Vu la loi n°13/2007/AN du 30 juillet 2007 portant loi d’orientation de l’éducation ; Vu le décret n°2017-0818/PRES/PM/MENA/MINEFID du 19 septembre 2017 portant définition du régime des bourses dans les enseignements post-primaire et secondaire et son modificatif n°2017-1072/PRES/PM/MENA/MINEFID du 10 novembre 2017 ; ARRETE 1 Article 1 : Sous réserve de contrôle approfondi les élèves du post-primaire dont les noms suivent sont déclarés par ordre de mérite, bénéficiaires de la bourse scolaire, au titre de l’année scolaire 2017-2018 : REGION DE LA BOUCLE DU MOUHOUN Bénéficiaires de la