Technology on the Battlefield by CSM Ronald T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia

Army Regulation 670–1 Uniforms and Insignia Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 1 September 1992 Unclassified SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 670–1 Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia This revision-- o Deletes the utility and durable press uniforms. o Adds new criteria for exceptions based on religious practices (para 1-7). o Adds grooming and hygiene statement (para 1-8d). o Adds wear policy for utility uniforms on deployment (para 1-10b). o Clarifies policy for blousing trousers (paras 3-5, 4-5, 5-5, 6-5). o Deletes old chapter 6. o Prescribes wear policy for the extended cold weather clothing system parka as an optional item (para 6-7). o Changes the physical fitness uniform to a clothing bag item (chap 13). o Revises wear policy and establishes possession dates for the Physical Fitness Uniform (chap 13 and App D). o Authorizes wear of black four-in-hand time with enlisted dress uniform (para 14-2c). o Authorizes wear of awards on AG 415 shirt (paras 14-10, 15-11, and 17-11). o Deletes AG 344 pantsuit and AG 344 skirt (chap 15). o Authorizes wear of blue slacks by selected females (para 20-7). o Adds chevrons and service stripes on the Army mess uniforms (paras 21-5d, 22- 5b, 23-5e, and 24-5e). o Adds soldiers authorized to wear organizational beret (para 26-3). o Clarifies possession policy on combat boots (para 26-4). o Authorizes wear of cold weather cap with black windbreaker (para 26-7). -

On the Military Utility of Spectral Design in Signature Management: a Systems Approach

National Defence University Series 1: Research Publications No. 21 On the Military Utility of Spectral Design in Signature Management: a Systems Approach On the Military Utility of Spectral Design in Signature On the Military Utility of Spectral Design in Signature Management: a Systems Approach Kent Andersson Kent Andersson National Defence University PL 7, 00861 HELSINKI Tel. +358 299 800 www.mpkk.fi ISBN 978-951-25-2998-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-951-25-2999-5 (PDF) ISSN 2342-9992 (print) ISSN 2343-0001 (web) Series 1, No. 21 The Finnish Defence Forces KENT ANDERSSON ON THE MILITARY UTILITY OF SPECTRAL DESIGN IN SIGNATURE MANAGEMENT: A SYSTEMS APPROACH Doctoral dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Military Sciences to be presented, with the consent of the Finnish National Defence University, for public examination in Sverigesalen, at the Swedish Defence University, Drottning Kristinas väg 37, in Stockholm, on Friday 13th of April at 1 pm. NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY HELSINKI 2018 NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY SERIES 1: RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS NO. 21 FINSKA FÖRSVARSUNIVERSITETET SERIE 1: FORSKINGSPUBLIKATIONER NR. 21 ON THE MILITARY UTILITY OF SPECTRAL DESIGN IN SIGNATURE MANAGEMENT: A SYSTEMS APPROACH KENT ANDERSSON NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY HELSINKI 2018 Kent Andersson: On the Military Utility of Spectral Design in Signature Management: a Sys- tems Approach National Defence University, Finland Series 1: Research Publications No. 21 Doctoral dissertation Finska Försvarshögskolan Publikationsserie 1: Forskingspublikationer nr. 21 Doktorsavhandling Author: Lt Col, Tech. Lic. Kent Andersson Supervising professor: Professor Jouko Vankka, National Defence University, Finland Preliminary examiners: Professor Harold Lawson, Prof. Emeritus, ACM, IEEE and INCOSE Fellow, IEEE Computer pioneer, Sweden Professor Christer Larsson, Lund University, Sweden Official opponents: Professor Jari Hartikainen, Finnish Defence Research Agency, Finland Professor Harold Lawson, Prof. -

Counterinsurgency in the Iraq Surge

A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in US History. By Matthew T. Buchanan Director: Dr. Richard Starnes Associate Professor of History, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Committee Members: Dr. David Dorondo, History, Dr. Alexander Macaulay, History. April, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations . iii Abstract . iv Introduction . 1 Chapter One: Perceptions of the Iraq War: Early Origins of the Surge . 17 Chapter Two: Winning the Iraq Home Front: The Political Strategy of the Surge. 38 Chapter Three: A Change in Approach: The Military Strategy of the Surge . 62 Conclusion . 82 Bibliography . 94 ii ABBREVIATIONS ACU - Army Combat Uniform ALICE - All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment BDU - Battle Dress Uniform BFV - Bradley Fighting Vehicle CENTCOM - Central Command COIN - Counterinsurgency COP - Combat Outpost CPA – Coalition Provisional Authority CROWS- Common Remote Operated Weapon System CRS- Congressional Research Service DBDU - Desert Battle Dress Uniform HMMWV - High Mobility Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle ICAF - Industrial College of the Armed Forces IED - Improvised Explosive Device ISG - Iraq Study Group JSS - Joint Security Station MNC-I - Multi-National-Corps-Iraq MNF- I - Multi-National Force – Iraq Commander MOLLE - Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment MRAP - Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (vehicle) QRF - Quick Reaction Forces RPG - Rocket Propelled Grenade SOI - Sons of Iraq UNICEF - United Nations International Children’s Fund VBIED - Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device iii ABSTRACT A NEW WAY FORWARD OR THE OLD WAY BACK? COUNTERINSURGENCY IN THE IRAQ SURGE. -

U.S. Army Board Study Guide Version 5.3 – 02 June, 2008

U.S. Army Board Study Guide Version 5.3 – 02 June, 2008 Prepared by ArmyStudyGuide.com "Soldiers helping Soldiers since 1999" Check for updates at: http://www.ArmyStudyGuide.com Sponsored by: Your Future. Your Terms. You’ve served your country, now let DeVry University serve you. Whether you want to build off of the skills you honed in the military, or launch a new career completely, DeVry’s accelerated, year-round programs can help you make school a reality. Flexible, online programs plus more than 80 campus locations nationwide make studying more manageable, even while you serve. You may even be eligible for tuition assistance or other military benefits. Learn more today. Degree Programs Accounting, Business Administration Computer Information Systems Electronics Engineering Technology Plus Many More... Visit www.DeVry.edu today! Or call 877-496-9050 *DeVry University is accredited by The Higher Learning Commission of the North Central Association, www.ncahlc.org. Keller Graduate School of Management is included in this accreditation. Program availability varies by location Financial Assistance is available to those who qualify. In New York, DeVry University and its Keller Graduate School of Management operate as DeVry College of New York © 2008 DeVry University. All rights reserved U.S. Army Board Study Guide Table of Contents Army Programs ............................................................................................................................................. 5 ASAP - Army Substance Abuse Program............................................................................................... -

GAO-12-707, WARFIGHTER SUPPORT: DOD Should Improve

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters GAO September 2012 WARFIGHTER SUPPORT DOD Should Improve Development of Camouflage Uniforms and Enhance Collaboration Among the Services GAO-12-707 September 2012 WARFIGHTER SUPPORT DOD Should Improve Development of Camouflage Uniforms and Enhance Collaboration Among the Services Highlights of GAO-12-707, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Since 2002, the military services have The military services have a degree of discretion regarding whether and how to introduced seven new camouflage apply Department of Defense (DOD) acquisition guidance for their uniform uniforms with varying patterns and development and they varied in their usage of that guidance. As a result, the colors—two desert, two woodland, and services had fragmented procedures for managing their uniform development three universal. In addition, the Army is programs, and did not consistently develop effective camouflage uniforms. GAO developing new uniform options and identified two key elements that are essential for producing successful outcomes estimates it may cost up to $4 billion in acquisitions: 1) using clear policies and procedures that are implemented over 5 years to replace its current consistently, and 2) obtaining effective information to make decisions, such as uniform and associated protective credible, reliable, and timely data. The Marine Corps followed these two key gear. GAO was asked to review the elements to produce a successful outcome, and developed a uniform that met its services’ development of new camouflage uniforms. This report requirements. By contrast, two other services, the Army and Air Force, did not addresses: 1) the extent to which DOD follow the two key elements; both services developed uniforms that did not meet guidance provides a consistent mission requirements and had to replace them. -

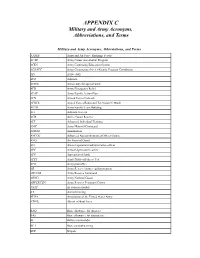

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

MILITARY and LAW ENFORCEMENT PRODUCT CATALOGUE FABBRICA D’ARMI PIETRO BERETTA Founded in 1526 and Based in Gardone Valtrompia, Italy

MILITARY AND LAW ENFORCEMENT PRODUCT CATALOGUE FABBRICA D’ARMI PIETRO BERETTA Founded in 1526 and based in Gardone Valtrompia, Italy. Time proven and operationally tested, the centuries have passed and simply underlined Beretta as one of the premium names in the defense and Law Enforcement sectors. Producing the widest range of small firearms in the world from the most state-of-the-art facilities in the industry, the oldest firearms factory (officially documented since 1526), and one of the most successful has been passed down through 15 generations of the Beretta family and now exports over 75% of the weapons produced to over 100 countries. Beretta`s firearms have been adopted as the standard issue sidearm for many armed forces, elite units and law enforcement agencies worldwide including the 92FS semiautomatic pistol which is the official handgun of the US Armed Forces. Believed by many to be the greatest pistol ever made, the 92FS has redefined the standard for operational reliability. The next generation of semiautomatic techno-polymer handguns have been given their benchmark by Beretta`s recently released Px4 Storm series and in the field of assault weapons the ARX100 automatic rifle platform and GLX160 grenade launcher are redefining the standard. The combination of high tech modern materials and ergonomics have led to the Mx4 Storm submachine gun and the Cx4 Storm Carbine, both equally formidable in hostile environments or with close protection units. 5 PX4 Storm SEMIAUTOMATIC PISTOL 19 90 Series SEMIAUTOMATIC PISTOL 27 80 Series SEMIAUTOMATIC PISTOL 33 CX4 Storm SEMIAUTOMATIC CARBINE 39 MX4 Storm Contents SUBMACHINE GUN 47 TX4 Storm TACTICAL SEMIAUTOMATIC SHOTGUN 51 ARX 100 WEAPON SYSTEM 69 GLX 160 A1 GRENADE LAUNCHER 75 70/90 ASSAULT RIFLE 79 TACTICAL CLOTHING 3 PX4 Storm PISTOL SEMIAUTOMATIC 5 MILITARY AND LAW ENFORCEMENT PRODUCT CATALOGUE Because Lives Depend On it The Beretta Px4 Storm pistol is the most advanced expression of technological and ergonomic features in a semiautomatic sidearm. -

TURKEY One of the 10 Countries That Has the Capability to Construct Warship in the World

CONTENTS ABOUT US 4 1st MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 5 2ND MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 23 4TH MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 44 5TH MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 55 6TH MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 70 7TH MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 83 8TH MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 93 ELECTRO-OPTICAL SYSTEMS MAIN MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 102 MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE GENERAL DIRECTORATE OF NAVAL SHIPYARDS 112 1st AIR MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 130 2ND AIR MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 147 3RD AIR MAINTENANCE FACTORY DIRECTORATE 174 Army Sewing & Tailoring WORKShops Directorate 191 NAVY Sewing & Tailoring WORKShops Directorate 196 AIR Sewing & Tailoring WORKShops Directorate 201 MOD PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTION PLANT 203 ABOUT US ASFAT Inc., a fully government owned entity, was established on 12 January 2018 under the Ministry of National Defence in accordance with the supplementary article #12 enacted for Act#1325. ASFAT Inc. utilizes over 30 years of experience in manufacturing, modernization, repair, maintenance and sustainment of 27 military factories and 3 naval shipyards with the qualified and expert labour force. While performing its functions, ASFAT Inc. aims to improve operational excellence by developing facilities, capabilities and capacities of military factories and shipyards. Being entitled to sign “Government-to-Government Agreements”, ASFAT Inc. plays an effective role to ease export processes of defence industry products. It offers and provides innovative solutions to friendly and allied nations in design, manufacture, maintenance, sustainment and training areas with a solution partner approach, via aiming the launching of lifecycle management fundamentals with the synergy created by public-private partnership. Thanks to the dynamism brought by its efficient organization and competent staff with international experience, ASFAT Inc. -

3823219745PL Safetysystems

Page 1 tblVendorData - Safety Systems Corporation 9/8/2005 Item# ItemDesc Mfr MfrItem# CateUnit CatPrice Discount% NetPrice AD2-35-AT05 Fleece, S.P.E.A.R., Jacket, Outerwear ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05 8 EA $124.00 20.00% $99.20 AD2-35-AT05/2XLL Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/2X-Large Long ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/2XLL 8 EA $154.00 25.00% $115.50 AD2-35-AT05/B/2XLR Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/2X-Large Regular ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/2XLR 8 EA $154.00 25.00% $115.50 AD2-35-AT05/B/SR Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/Small Regular ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/SR 8 EA $124.00 25.00% $93.00 AD2-35-AT05/LL Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/Large Long ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/LL 8 EA $124.00 25.00% $93.00 AD2-35-AT05/LR Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/Large Regular ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/LR 8 EA $124.00 25.00% $93.00 AD2-35-AT05/MR Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/Medium Regular ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/MR 8 EA $124.00 25.00% $93.00 AD2-35-AT05/XLL Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/X-Large Long ADVENTURE TECH, INC. 35-AT05/XLL 8 EA $124.00 25.00% $93.00 AD2-35-AT05/XLR Jacket,S.P.E.A.R./Fleece/Black/X-Large Regular ADVENTURE TECH, INC. -

U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command – Soldier Center

5/29/2020 UNCLASSIFIED U.S. ARMY COMBAT CAPABILITIES DEVELOPMENT COMMAND – SOLDIER CENTER Flame Resistant Materials and Soldier Sustainability Margaret Auerbach Textile Technologist Distribution Statement A: Approved for public release. Emerging Materials Development Team Soldier Protection and Survivability Directorate 20 May 2020 UNCLASSIFIED 1 UNCLASSIFIED FLAME RESISTANT MATERIALS AND SOLDIER SUSTAINABILITY Objective To provide an overview on the health and environmental issues associated with the use of inherently flame resistant (FR) or FR treated materials in protective clothing and equipment as it relates to soldier survivability and sustainability. UNCLASSIFIED 2 2 1 5/29/2020 UNCLASSIFIED FLAME RESISTANT MATERIALS AND SOLDIER SUSTAINABILITY FLAME RESISTANT UNIFORMS – IN FACT, ALL MATERIAL CHANGES EVOLVE TO MEET SOLDIERS' NEEDS UNCLASSIFIED 3 3 UNCLASSIFIED FLAME RESISTANT MATERIALS AND SOLDIER SUSTAINABILITY Primary goal of FR materials: Sustainability of the Soldier To provide soldiers with protection against specific threats to prevent burn injury provide additional time to escape from flames/fire https://www.pinterest.com/virgilusa/vietnam-war-photos/ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/jul/15/first-photograph-ied-afghanistan-roadside-bomb UNCLASSIFIED 4 4 2 5/29/2020 UNCLASSIFIED FLAME RESISTANT MATERIALS AND SOLDIER SUSTAINABILITY In Vietnam, helicopters were used to - transport troops, supplies and equipment, - aid ground troops with additional firepower - evacuate killed or wounded soldiers In 1968, the Army was reporting an increasing number of deaths or burn injuries as a result of post-crash fires. Soldiers were actually surviving the impact during helicopter crashes but needed more time to get out. Egress times to survive: Large transport planes - 90 seconds Helicopters - less than 17 seconds to make it outside the fireball Auerbach, M., Ramsay, J., D’Angelo, P., Cameron, S.,Proulx, G., Kaplan, J., Grady, M., and Coyne, M. -

Medical Mission a Part of Bigger Operation by Spc

July 12, 2010 | Issue 24 Medical mission a part of bigger operation By Spc. Samuel Soza wanee, Ill. native. “We’re working 367 MPAD, USD-S PAO with the [Wasit Provincial Recon- struction Team] to maybe work AL KUT – The challenge of providing some exam tables, blood pressure medical evaluations and supplies to resi- cuffs, or other pieces of medical dents in areas such as al-Kut can be sig- equipment into the two clinics we nificant for military providers. Still, the have identified here.” need is there. Before the visit, local residents Ask the Soldiers of 1st Battalion, 10th were polled on issues they would Field Artillery Regiment, 3rd Heavy Bri- like addressed. Many medical gade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division, evaluations yielded minor cases in who set up shop June 24 in the Iraqi Fed- which Soldiers were able to assist eral Police headquarters building, which on the spot by providing simple serves the city’s Anwar and Falahiyah solutions such as washing solu- districts. That day, they assisted more than tions, foot creams, toothbrushes 100 residents with various medical issues. and toothpaste. Capt. Matthew Holt, a 1st Bn., 10th FA Holt has taken his medical skills Regt. physician’s assistant from Atlanta, outside the COB to Iraqis on medi- Photo by Spc. Samuel Soza estimated 150 Iraqi citizens came to the cal operations. This was his third Spc. Miguel Ocegueda, a medic with 1st Bn., 10th FA Regt. and native of Austin, Texas, looks over an x-ray headquarters and were given one-on-one “med-op” this deployment. -

IET Soldier’S Handbook TRADOC Pamphlet 600-4 1 October 2003

IET Soldier’s Handbook TRADOC Pamphlet 600-4 1 October 2003 HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY United States Army Training and Doctrine Command Fort Monroe, Virginia 23651-5000 FOREWORD This handbook is a handy pocket reference for subjects in which you must maintain proficiency. It condenses information from field manuals, training circulars, Army regulations, and other sources. You will need this handbook in initial-entry training (IET). Carry it with you at all times. Use it to review the training you will receive and to prepare for proficiency testing. It will also be useful throughout your military career. This handbook addresses both general subjects and selected combat tasks. It includes evaluation guides to test your knowledge. You must know this information in order to be an effective soldier. The information on selected combat tasks is important, regardless of your grade or military occupational specialty (MOS). Unless this handbook states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. DEPARTMENT O F THE ARMY HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND Fort Monroe, Virginia 23651-5000 PERSONNEL—GENERAL IET SOLDIER'S HANDBOOK (2 October 2003) Chapter 1. General Subjects ...............................................1-1 Army History ......................................................................... 1-1 Heritage and Traditions ......................................................1-3 Army Organization..................................................................1-5 Chain of