Soul Survivor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aretha Franklin's Gendered Re-Authoring of Otis Redding's

Popular Music (2014) Volume 33/2. © Cambridge University Press 2014, pp. 185–207 doi:10.1017/S0261143014000270 ‘Find out what it means to me’: Aretha Franklin’s gendered re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’ VICTORIA MALAWEY Music Department, Macalester College, 1600 Grand Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55105, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In her re-authoring of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’, Aretha Franklin’s seminal 1967 recording features striking changes to melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. Musical analysis and transcription reveal Franklin’s re-authoring techniques, which relate to rhetorical strategies of motivated rewriting, talking texts and call-and-response introduced by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The extent of her re-authoring grants her status as owner of the song and results in a new sonic experience that can be clearly related to the cultural work the song has performed over the past 45 years. Multiple social movements claimed Franklin’s ‘Respect’ as their anthem, and her version more generally functioned as a song of empower- ment for those who have been marginalised, resulting in the song’s complex relationship with feminism. Franklin’s ‘Respect’ speaks dialogically with Redding’s version as an answer song that gives agency to a female perspective speaking within the language of soul music, which appealed to many audiences. Introduction Although Otis Redding wrote and recorded ‘Respect’ in 1965, Aretha Franklin stakes a claim of ownership by re-authoring the song in her famous 1967 recording. Her version features striking changes to the melodic content, vocal delivery, lyrics and form. -

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

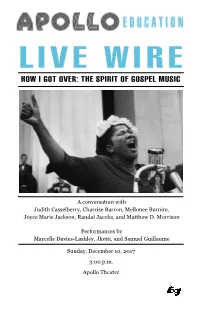

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

P36-40 Layout 1

lifestyle TUESDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2016 MUSIC & MOVIES Bob Dylan sends speech for Nobel ceremony usic icon Bob Dylan won't be at the Nobel prize cere- in a letter on November 16 that he would not attend the cere- "Absolutely. If it's at all possible." mony this week to accept his award, but he has sent mony because he had "pre-existing commitments", in an Academy member Swedish writer Per Wastberg accused Malong a speech to be read aloud, the Nobel founda- announcement that did not come as a surprise to observers. Dylan of being "impolite and arrogant", and said it was tion said yesterday. The 75-year-old, whose lyrics have influ- Several other prize winners have skipped the Nobel ceremony "unprecedented" that the academy did not know if Dylan enced generations of fans, has had a subdued response to the in the past for various reasons-Doris Lessing, who was too old; intended to pick up his award. But the first songwriter to win honor, remaining silent for weeks following the news in Harold Pinter, because he was hospitalized, and Elfriede the prestigious award in literature is expected to come to October he had won the prize for literature. "This year's Jelinek, who has social phobia. Stockholm early next year. Nobel laureates are honored every Laureate in Literature, Bob Dylan, will not be participating in Dylan did not say a word about his prize on the day it was year on December 10 -- the anniversary of the death of prize's the Nobel Week but he has provided a speech which will be announced, October 13, when he was performing in Las founder Alfred Nobel, a Swedish industrialist, inventor and read at the banquet," the foundation said in a statement. -

Press Release for IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Monday, November 25, 2019 at Noon ET Headshot Available Here

Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Monday, November 25, 2019 at Noon ET Headshot available here. America to Celebrate the Artistic Achievements of Earth, Wind & Fire, Sally Field, Linda Ronstadt, , and Michael Tilson Thomas on Sunday, December 8, 2019 (WASHINGTON)—Two-time Grammy Award® winner and 2017 Kennedy Center Honors recipient LL COOL J will host the 42nd annual Kennedy Center Honors on . The Honors Gala will be recorded for broadcast on the CBS Television Network for the 42nd year as a two-hour primetime special to air on Sunday, December 15 (8:00–10:00 p.m., ET/PT). This will be LL COOL J’s first time hosting the special. As previously announced, the recipients of the 2019 Kennedy Center Honors will be R&B collective , actress , singer , children’s television program , and conductor and musical visionary . The 42nd annual Kennedy Center Honors marks the first time a television program will receive the award. In a star-studded celebration on the Kennedy Center Opera House stage on Sunday, December 8, the 2019 Honorees will be saluted by today’s leading performers from New York, Hollywood, and the arts capitals of the world, accepting the recognition and gratitude of their peers through performances and tributes. The Honors recipients are recognized for their lifetime contributions to American culture through the performing arts— whether in dance, music, theater, opera, motion pictures, or television—and are confirmed by the executive committee of the Center’s board of trustees. The primary criterion in the selection process is excellence. The Honors are not designated by art form or category of artistic achievement; over the years, the selection process has produced a balance among the various arts and artistic disciplines. -

THE GOD GROOVE by DAVID RITZ

For immediate release Contact: Yona Deshommes Associate Director of Publicity [email protected] (212) 698-7566 THE GOD GROOVE By DAVID RITZ David Ritz has written over 50 books. Ritz’s job as a ghostwriter molded his prime directive into becoming the voice of who he was writing about, rejecting the temptation to implant his/her own point of view into the story. So, you’ve never really seen a clear portrait of the man himself until The God Groove, his first memoir. Seeking an escape from death by boredom in advertising, Ritz began his 40-plus year journey as a writer and ghostwriter with a simple but seemingly impossibly goal: to be Ray Charles’ first biographer. What began with a 32-year-old husband and father of two’s plane ride from Dallas to Los Angeles to bang on Ray’s front door began an odyssey from which he never truly returned as the same man. The God Groove places Ritz in rooms with artists, musicians and academics who have shaped the last 50 years in American culture: the late Aretha Franklin, Blues legend Etta James, and the tortured genius of Marvin Gaye, for whom he writes the titles to the now- classic “Sexual Healing”, the first stone on the path to Ritz becoming a songwriter in his own right. For immediate release Contact: Yona Deshommes Associate Director of Publicity [email protected] (212) 698-7566 Ritz documents the thoughts and feelings of late bluesman B.B. King on a tour bus through the cotton fields of the deep South. -

TV GOSPEL TIME 5 October 28, 1962

TV GOSPEL TIME 1 October 7, 1962 Washington Temple Celestial Chorus (ensemble, soloist, Laura Brown): Have You Been Down To The River Washington Templettes: Tired James Lowe: Peace In The Valley Washington Templettes: Holy City Celestial Chorus (Louise Bynoe, Robert Madison, Laura Brown, Robert Taylor): God Is Moving James Lowe and Chorus: God Out A Rainbow In The Sky James Lowe: His Eye Is On The Sparrow Celestial Chorus (ensemble, soloists, Henry Coston, Robert Taylor, Robert Madison): Stand Still TV GOSPEL TIME 2 November 11, 1962 Washington Temple Celestial Chorus (ensemble): I’ll Go With Him Lorraine Ellison Singers: Yes God Will Paulilne Ellison: What God Can Do James Wyns: His Eye Is On The Sparrow Celestial Chorus (soloist James Wyns): Softly And Tenderly Lorraine Ellison Singers: Oh What A Joy Lorraine Ellison: Walk With Christ Celestial Chorus (ensemble, soloist Ernest Alexander): Ninety-Nine And A Half Won’t Do TV GOSPEL TIME 3 November 25, 1962 Voices Of Shiloh (ensemble, soloist Esther Anthony): I’m Going To Wait On The Lord Tears Of Music: Brother Afar Clifton West: Wake Up In Glory Tears Of Music: Tramping Voices Of Shiloh: Joshua Fit The Battle Of Jericho Tears Of Music: No Hiding Place Alma Ellison: I Want Jesus To Walk With Me Voices Of Shiloh (ensemble): All Over God’s Heaven (I Got Shoes) TV GOSPEL TIME 4 December 2, 1962 Mt. Sinai Gospel Chorus (ensemble, soloist Marie McDougal): Come On, Children, Let’s Sing Twilight Gospel Singers: Does Jesus Care Twilight Gospel Singers (soloist Ann Walker): Who Twilight Gospel Singers (soloist Carolyn Bush): I’m Willing To Go Mt. -

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Ruth Frankel Professor Swedberg CAS WS214 May 2, 2013 Carole

Ruth Frankel Professor Swedberg CAS WS214 May 2, 2013 Carole King: A Consequential Female Artist in Achievement and Message Carole King, a Brooklyn born singersongwriter, most associated with the music of the 1960s and 1970s, is significant in that she, according to her biographer James Perone, “almost singlehandedly opened the doors of popular music songwriting to women” (1). She also became the first female artist in American popular music in complete control of her own work. Her writing was prolific. She has written 500 copyrighted songs throughout her career and has had tremendous commercial success (Havranek 236). King’s greatest success was the release of the 1973 album Tapestry, which remained on the charts for 302 weeks (Perone 6). Though her cultural impact is often underappreciated, Carole King has been an important contributor to advancement of women in the music industry and a positive role model to the female audiences of her generation. It is even hard to find academic sources reflecting the success and cultural attributions of King. Overall, it appears that sexism has faded the memory of Carole King’s contribution to women in music. Again and again, King impact has not been recognized or remembered. For example, in the book Go, Girl, Go!: The Women’s Revolution in Music by James Dickerson, King’s name is mentioned only once. Dickerson writes, “Carly Simon and Carole King were the two most successful singersongwriters of the decade, and of the two, it was Carly who was dazzling the world with her toothy smile and sexy album covers” (77).