External World Skepticism Films311

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

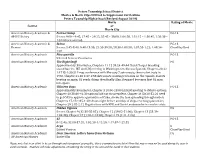

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

Living in the Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture

Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture Kacmaz Erk, G. (2016). Living in The Matrix: Virtual Reality Systems and Hyperspatial Representation in Architecture. The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts, 13-25. Published in: The International Journal of New Media, Technology and the Arts Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 Gul Kacmaz Erk. Available under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The use of this material is permitted for non-commercial use provided the creator(s) and publisher receive attribution. No derivatives of this version are permitted. Official terms of this public license apply as indicated here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins 2016 Primary Election Results: So Goes City Island

Periodicals Paid at Bronx, N.Y. USPS 114-590 Volume 45 Number 4 May 2016 One Dollar Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins By VIRGINIA DANNEGGER and KAREN NANI ria Piri, concession stand managers Jim and singlehandedly did the job of several and Sue Goonan, and equipment manager people. Even though his boys aged out of Lou Lomanaco. Several of these board the league, John still dedicates his time to members have served multiple terms on the help.” He presented John with a framed board. CILL jersey and a plaque in appreciation Mr. Esposito gave special thanks to for his support of the league and the City Photos by RICK DeWITT the outgoing president, John Tomsen, Island community. It was a chilly start to the 2016 Little League season on April 9, but the baseball tradi- who threw out the first pitch. “John has “As many of you know, volunteering tion dating back to 1900 is alive and warm on City Island. There are major, minor and time is a family commitment. Whether it t-ball teams competing once again this season. The ceremonial first pitch was thrown been president of the CILL since 2009 by outgoing president John Tomsen, who was also awarded a framed jersey by the Continued on page 19 new league president, Dom Esposito (right, top photo). New York State Assemblyman Michael Benedetto joined Catherine Ambrosini, Mr. Esposito and Mr. Tomsen (second photo, l. to r.) for the season opener. The American Legion color guard bearers led the teams in the “Star Spangled Banner.” As the weather warms up, head down to Ambro- 2016 Primary Election Results: sini Field next to P.S. -

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Read Book Simulacron-3 1St Edition

SIMULACRON-3 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel F Galouye | 9781612420202 | | | | | Simulacron-3 1st edition PDF Book The groups' long time arranger Larry Cansler had a successful career in the studios in Los Angeles scoring many movies including The Gambler series , variety shows, the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and many national commercials. By the mids, frontman Kenny Rogers had embarked on a solo music career, becoming one of the top-selling country artists of all time. Original Title. Now in its second year, an album of live versions of the "Calico" songs and hits like "Ruby," "Reuben James" and "Just Dropped In" could have sold quite well, bringing proven hits to the Jolly Rogers label at the same time. Terry later said that this made him feel like one of Gladys Knight 's Pips. Dec 19, Franky rated it really liked it Shelves: the-hard-challenge , sci-fi. Thankfully, it also offers the reader some moral opinions on how to proceed in the face of these unanswerable questions. Follow Blog via Email Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email. In any event, what was Simulacron-3 about? The recording was a Kin Vassy era performance of an unknown date. You have a tenable mind George. Enter the private company Reactions, Inc. Dick would produced more work in about the same life span. Most of the sociological premises having to do with opinion polling, the reason for the simulations, have been trimmed. The third single from the album, a version of Merle Haggard 's "Today I Started Loving You Again" reached the lower regions of the country charts in mid This theme of choice is crucial to the plot of The Matrix in the sequels. -

Images of the Religious in Horror Films

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 5 Issue 2 October 2001 Article 7 October 2001 The Sanctification of ear:F Images of the Religious in Horror Films Bryan Stone Boston University School of Theology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stone, Bryan (2001) "The Sanctification of ear:F Images of the Religious in Horror Films," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 5 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol5/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sanctification of ear:F Images of the Religious in Horror Films Abstract Horror film functions both as a threat and a catharsis by confronting us with our fear of death, the supernatural, the unknown and irrational, ''the other" in general, a loss of identity, and forces beyond our control. Over the last century, religious symbols and themes have played a prominent and persistent role in the on-screen construction of this confrontation. That role is, at the same time, ambiguous insofar as religious iconography has become unhinged from a compelling moral vision and reduced to mere conventions that produce a quasi-religious quality to horror that lacks the symbolic power required to engage us at the deepest level of our being. Although religious symbols in horror films are conventional in their frequent use, they may have lost all connection to deeper human questions. -

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies

C.A.S.E. Recommended Adoption Movies Movies Appropriate for Children: Movies Appropriate for Adults: Angels in the Outfield Admission Rear Window Anne of Green Gables Antwone Fisher Second Best Annie (both versions) Babbette’s Feast Secrets and Lies Cinderella w/Brandy & Whitney Houston Blossoms in the Dust Singing In The Rain Despicable Me Catfish & Black Bean Soldiers Sauce Despicable Me 2 Children of Paradise St. Vincent Free Willy Cider House Rules Star Wars Trilogy Harry Potter series Cinema Paradiso The 10 Commandments Kung Fu Panda (1 and 2) Citizen Kane/Zelig The Big Wedding Like Mike CoCo—The Story of CoCo The Deep End of the Lilo and Stitch Chanell Ocean Little Secrets Come Back Little Sheba The Joy Luck Club Martian Child Coming Home The Key of the Kingdom Meet the Robinsons First Person Plural The King of Masks Prince of Egypt Flirting with Disaster The Miracle Stuart Little Greystroke The Official Story Stuart Little 2 High Tide The Searchers Superman & Superman (2013) I Am Sam The Spit Fire Grill Tarzan Into the Arms of The Truman Show The Country Bears Strangers The Kid Juno Thief of Bagdad The Lost Medallion King of Hearts To Each His Own The Odd Life of Timothy Green Les Miserables White Oleander The Rescuers Down Under Lovely and Amazing Loggerheads The Jungle Book Miss Saigon Then She Found Me Orphans Immediate Family Philomena www.adoptionsupport.org . -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

Meyer Tech Pak012617.Indd

• Technical Information • Policies & Procedures • Fee Schedule for Rental & Services LOAD-IN AREA The loading dock is located on stage level, directly off upstage right. The dock has one 8’-0” wide x 10’-0” high (2.44m x 3.05m) overhead door. Dock height is 24” (.61m). There is NO leveler, and there is NO truck ramp. The loading area is 16’ wide x 22’ long with 12’ ceilings, in a wedge shape. Access to stage is through a 10’ wide x 11’ high overhead door upstage right. Access to the dressing rooms is by stairs or by elevator. CARPENTRY Seating Capacity Maximum Capacity: 1011 Orchestra 537 Grand Tier: 90 Mezzanine: 384 Handicapped Accessible: 8 Additional on Grand Tier Level Stage Dimensions Proscenium w: 49’-6” (15.09m) h:23’-0” (7.01m) Depth (plaster to back wall) 28’-0” (8.53m) Apron Curved 5’-0” (1.52m) at centerline Wing Space • Stage right 10’-0” (~3.05m) • Stage left 13’-0” (~3.96m) Orchestra Pit none Stage to Audience 4’-0” (1.21m) NFORMATION Stage Floor Material: 1/4” hardboard (Duron) I Color: Black Condition: Good Sub floor: 1 layer of 3/4” plywood 2x4 sleepers (24” O.C.) on resilient pads House Drapery: House Curtain- Scarlet; Manual Fly Item Number Material WxH Legs 8 black velour 10’ x 25’ (3.05m x 7.62m) Borders 4 black velour 60’ x 10’ (18.23m x 3.05m) Full Black 2 black velour 60’ x 25’ (18.23m x 7.62m) Line Set Data: Grid height: 53’-9” (16.38m) High trim: 50’-11” (15.52m) Low trim: 5’-8” (1.72m) Total Line Sets: 26 single purchase Arbor Capacity: 1500 lbs (680kg) ECHNICAL Weight Available: 8702 lbs (3947kg) Weight Size: 19 lbs (8.6 kg) Pipe Length: 60’-0” (18.29m) T Pipe size: 26 @ 1-1/2” Schedule 40 Lock Rail: Stage Left, stage level Line Plot: Enclosed Shop Area: There is NO on-site scenery shop, and there is no off-stage area for working on scenery. -

The Korean Wave As a Localizing Process: Nation As a Global Actor in Cultural Production

THE KOREAN WAVE AS A LOCALIZING PROCESS: NATION AS A GLOBAL ACTOR IN CULTURAL PRODUCTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Ju Oak Kim May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Department of Journalism Nancy Morris, Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Patrick Murphy, Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Dal Yong Jin, Associate Professor, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University © Copyright 2016 by Ju Oak Kim All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation research examines the Korean Wave phenomenon as a social practice of globalization, in which state actors have promoted the transnational expansion of Korean popular culture through creating trans-local hybridization in popular content and intra-regional connections in the production system. This research focused on how three agencies – the government, public broadcasting, and the culture industry – have negotiated their relationships in the process of globalization, and how the power dynamics of these three production sectors have been influenced by Korean society’s politics, economy, geography, and culture. The importance of the national media system was identified in the (re)production of the Korean Wave phenomenon by examining how public broadcasting-centered media ecology has control over the development of the popular music culture within Korean society. The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS)’s weekly show, Music Bank, was the subject of analysis regarding changes in the culture of media production in the phase of globalization. In-depth interviews with media professionals and consumers who became involved in the show production were conducted in order to grasp the patterns that Korean television has generated in the global expansion of local cultural practices.