Normative Interfaces and Discourses in Super Mario Maker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ Systems

NTR-A2DP-UKV INSTRUCTIONINSTRUCTION BOOKLETBOOKLET (CONTAINS(CONTAINS IMPORTANTIMPORTANT HEALTHHEALTH ANDAND SAFETYSAFETY INFORMATION)INFORMATION) [0610/UKV/NTR] WIRELESS DS SINGLE-CARD DOWNLOAD PLAY THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES DOWNLOADED FROM ONE GAME CARD. This seal is your assurance that Nintendo 2–4 has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence WIRELESS DS MULTI-CARD PLAY in workmanship, reliability and THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES WITH EACH NINTENDO DS SYSTEM CONTAINING A entertainment value. Always look SEPARATE GAME CARD. for this seal when buying games and 2–4 accessories to ensure complete com- patibility with your Nintendo Product. Thank you for selecting the NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ systems. IMPORTANT: Please carefully read the important health and safety information included in this booklet before using your Nintendo DS system, Game Card, Game Pak or accessory. Please read this Instruction Booklet thoroughly to ensure maximum enjoyment of your new game. Important warranty and hotline information can be found in the separate Age Rating, Software Warranty and Contact Information Leaflet. Always save these documents for future reference. This Game Card will work only with Nintendo DS systems. IMPORTANT: The use of an unlawful device with your Nintendo DS system may render this game unplayable. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE COPYRIGHTS OF GAME, SCENARIO, MUSIC AND PROGRAM, RESERVED BY NINTENDO. TM, ® AND THE NINTENDO DS LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This product uses the LC Font by Sharp Corporation, except some characters. LCFONT, LC Font and the LC logo mark are trademarks of Sharp Corporation. -

The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games

The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Katharine Phelps Humanities 497W December 15, 2007 Just remember that my being a woman doesn't make me any less important! --Faris Final Fantasy V 1 The Princess and the Platformer: The Evolving Heroine in Nintendo Adventure Games Female characters, even as a token love interest, have been a mainstay in adventure games ever since Nintendo became a household name. One of the oldest and most famous is the princess of the Super Mario games, whose only role is to be kidnapped and rescued again and again, ad infinitum. Such a character is hardly emblematic of feminism and female empowerment. Yet much has changed in video games since the early 1980s, when Mario was born. Have female characters, too, changed fundamentally? How much has feminism and changing ideas of women in Japan and the US impacted their portrayal in console games? To address these questions, I will discuss three popular female characters in Nintendo adventure game series. By examining the changes in portrayal of these characters through time and new incarnations, I hope to find a kind of evolution of treatment of women and their gender roles. With such a small sample of games, this study cannot be considered definitive of adventure gaming as a whole. But by selecting several long-lasting, iconic female figures, it becomes possible to show a pertinent and specific example of how some of the ideas of women in this medium have changed over time. A premise of this paper is the idea that focusing on characters that are all created within one company can show a clearer line of evolution in the portrayal of the characters, as each heroine had her starting point in the same basic place—within Nintendo. -

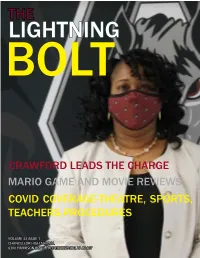

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

Super Mario 64 Manual

NUS-P-NSMP-NEU6 INSTRUCTION BOOKLET SPIELANLEITUNG MODE D’EMPLOI HANDLEIDING MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES MANUALE DI ISTRUZIONI TM Thank you for selecting the SUPER MARIO 64™ Game Pak for the 64 Nintendo® System. WARNING : PLEASE CAREFULLY READ WAARSCHUWING: LEES ALSTUBLIEFT EERST OBS: LÄS NOGA IGENOM THE CONSUMER INFORMATION AND ZORGVULDIG DE BROCHURE MET CONSU- HÄFTET “KONSUMENT- PRECAUTIONS BOOKLET INCLUDED MENTENINFORMATIE EN WAARSCHUWINGEN INFORMATION OCH SKÖTSE- WITH THIS PRODUCT BEFORE USING DOOR, DIE BIJ DIT PRODUCT IS MEEVERPAKT, LANVISNINGAR” INNAN DU CONTENTS YOUR NINTENDO® HARDWARE VOORDAT HET NINTENDO-SYSTEEM OF DE ANVÄNDER DITT NINTENDO64 SYSTEM, GAME PAK, OR ACCESSORY. SPELCASSETTE GEBRUIKT WORDT. TV-SPEL. HINWEIS: BITTE LIES DIE VERSCHIEDE- LÆS VENLIGST DEN MEDFØL- ADVERTENCIA: POR FAVOR, LEE CUIDADOSA- NEN BEDIENUNGSANLEITUNGEN, DIE GENDE FORBRUGERVEJEDNING OG MENTE EL SUPLEMENTO DE INFORMACIÓN SOWOHL DER NINTENDO HARDWARE, HÆFTET OM FORHOLDSREGLER, English . 4 AL CONSUMIDOR Y EL MANUAL DE PRECAU- WIE AUCH JEDER SPIELKASSETTE INDEN DU TAGER DIT NINTENDO® CIONES ADJUNTOS, ANTES DE USAR TU BEIGELEGT SIND, SEHR SORGFÄLTIG SYSTEM, SPILLE-KASSETTE ELLER CONSOLA NINTENDO O CARTUCHO . DURCH! TILBEHØR I BRUG. Deutsch . 24 ATTENTION: VEUILLEZ LIRE ATTEN- ATTENZIONE: LEGGERE ATTENTAMENTE IL HUOMIO: LUE MYÖS KULUTTA- TIVEMENT LA NOTICE “INFORMATIONS MANUALE DI ISTRUZIONI E LE AVVERTENZE JILLE TARKOITETTU TIETO-JA ET PRÉCAUTIONS D’EMPLOI” QUI PER L’UTENTE INCLUSI PRIMA DI USARE IL HOITO-OHJEVIHKO HUOLEL- 64 ACCOMPAGNE CE JEU AVANT D’UTILI- NINTENDO® , LE CASSETTE DI GIOCO O GLI LISESTI, ENNEN KUIN KÄYTÄT Français . 44 SER LA CONSOLE NINTENDO OU LES ACCESSORI. QUESTO MANUALE CONTIENE IN- NINTENDO®-KESKUSYKSIK- CARTOUCHES. FORMAZIONI IMPORTANTI PER LA SICUREZZA. KÖÄSI TAI PELIKASETTEJASI. -

SUPER MARIO 64 DS NINTENDO Icon to Load the Game

NTR-ASMP-UKV INSTRUCTION BOOKLET (CONTAINS IMPORTANT HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION) [0610/UKV/NTR] This seal is your assurance that Nintendo has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence in workmanship, reliability and entertainment value. Always look for this seal when buying games and accessories to ensure complete com- patibility with your Nintendo Product. Thank you for selecting the SUPER MARIO™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ systems. IMPORTANT: Please carefully read the important health and safety information included in this booklet before using your Nintendo DS system, Game Card, Game Pak or accessory. Please read this Instruction Booklet thoroughly to ensure maximum enjoyment of your new game. Important warranty and hotline information can be found in the separate Age Rating, Software Warranty and Contact Information Leaflet. Always save these documents for future reference. This Game Card will work only with Nintendo DS systems. IMPORTANT: The use of an unlawful device with your Nintendo DS system may render this game unplayable. © 2004 – 2005 NINTENDO. TM, ® AND THE NINTENDO DS LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. © 2005 NINTENDO. 4 Contents Story . 5 Camera Controls . 26 Starting the Game . 6 Changing Caps . 28 Basic Controls . 8 Changing Characters . 29 Essential Moves . 14 Items . 30 Character-Specific Moves . 18 Mini-Games . 32 Adventure Mode . 22 VS Battles . 34 Dual Screens . 23 Ask Princess Peach! . 36 In this user manual, a red border on a screen shot signifies the top screen and a blue border signifies the Touch Screen. STORY “Please cOme to the castle. I’ve baked a cake for you. -

Super Mario 64 Was Proclaimed by Many As "The Greatest Video Game

The People Behind Mario: When Hiroshi Yamauchi, president of Nintendo Co., Ltd. (NCL), hired a young art student as an apprentice in 1980, he had no idea that he was changing video games forever. That young apprentice was none other than the highly revered Shigeru Miyamoto, the man behind Mario. Miyamoto provided the inspiration for each Mario game Nintendo produces, as he still does today, with the trite exception of the unrelated “Mario-based” games produced by other companies. Just between the years 1985 and 1991, Miyamoto produced eight Mario games that went on to collectively sell 70 million copies. By record industry standards, Miyamoto had gone 70 times platinum in a brief six years. When the Nintendo chairman Gunpei Yokoi was assigned to oversee Miyamoto when he was first hired, Yokoi complained that “he knows nothing about video games” (Game Over 106). It turned out that the young apprentice knew more about video games than Yokoi, or anyone else in the world, ever could. Miyamoto’s Nintendo group, “R&D4,” had the assignment to come up with “the most imaginative video games ever” (Game Over 49), and they did just that. No one disagrees when they hear that "Shigeru is to video gaming what John Lennon is to Music!" (www.nintendoland.com) As soon as Miyamoto and Mario entered the scene, America, Japan, and the rest of the world had become totally engrossed in “Mario Mania.” Before delving deeply into the character that made Nintendo a success, we must first take a look at Nintendo, and its leader, Hiroshi Yamauchi. -

“We Are Mario!” Super Nintendo World Grand

さ March 18, 2021 “WE ARE MARIO!” SUPER NINTENDO WORLD GRAND OPENING TODAY Shigeru Miyamoto, Creator of Super Mario and Guests Led Countdown to the Grand Opening of the World's First Nintendo Theme Park Area OSAKA (March 18, 2021) – Universal Studios Japan hosted the grand opening of SUPER NINTENDO WORLD, bringing to life a themed and immersive land featuring Nintendo’s legendary worlds, characters and adventures where guests play inside their favorite Nintendo games. Shigeru Miyamoto, Creator of Super Mario and J.L. Bonnier, President and CEO of Universal Studios Japan kicked off the festivities at Super Star Plaza. Popular Nintendo characters Mario, Luigi, Princess Peach and Toad, as well as SUPER NINTENDO WORLD team members, cheered on guests in the momentous grand opening of SUPER NINTENDO WORLD. Super Mario fans jumped in Mario’s iconic pose and cheered “WE ARE MARIO!” while festive confetti burst into the sky to commemorate the occasion. Guests then made their way through the warp pipe entrance and into the new immersive land. The moment guests were transported from the warp pipe into Peach’s Castle, they were captivated and expressed their excitement by posing like Mario and taking photos. ©Nintendo Nintendo and Universal Parks & Resorts Executives made the following statements: Shigeru Miyamoto, Creator of Super Mario SUPER NINTENDO WORLD brings the world of Mario games to life. The moment you enter the park, you will be amazed at how real everything feels. But that’s not all. The creative team at Universal has not only done a great job recreating the Mushroom Kingdom, but they have also made some amazing rides. -

Female Fighters

Press Start Female Fighters Female Fighters: Perceptions of Femininity in the Super Smash Bros. Community John Adams High Point University, USA Abstract This study takes on a qualitative analysis of the online forum, SmashBoards, to examine the way gender is perceived and acted upon in the community surrounding the Super Smash Bros. series. A total of 284 comments on the forum were analyzed using the concepts of gender performativity and symbolic interactionism to determine the perceptions of femininity, reactions to female players, and the understanding of masculinity within the community. Ultimately, although hypermasculine performances were present, a focus on the technical aspects of the game tended to take priority over any understanding of gender, resulting in a generally ambiguous approach to femininity. Keywords Nintendo; Super Smash Bros; gender performativity; symbolic interactionism; sexualization; hypermasculinity Press Start Volume 3 | Issue 1 | 2016 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Adams Female Fighters Introduction Examinations of gender in mainstream gaming circles typically follow communities surrounding hypermasculine games, in which members harass those who do not conform to hegemonic gender norms (Consalvo, 2012; Gray, 2011; Pulos, 2011), but do not tend to reach communities surrounding other types of games, wherein their less hypermasculine nature shapes the community. The Super Smash Bros. franchise stands as an example of this less examined type of game community, with considerably more representation of women and a colorful, simplified, and gore-free style. -

1- My Nintendo Mario and Yoshi Sweepstakes Official Rules

MY NINTENDO MARIO AND YOSHI SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN THIS SWEEPSTAKES. Purchase will not improve odds of winning. The My Nintendo Mario and Yoshi Sweepstakes (“Sweepstakes”) is sponsored by Nintendo of America Inc., 4600 150th Ave NE, Redmond, WA 98052, USA (“Sponsor”). Eligibility: Sweepstakes is open only to individuals who are residents of the 50 United States, District of Columbia and Canada (excluding Quebec) and are at least 13 years old. All participants under 18 years old (or under the legal age of majority in the player’s jurisdiction of residence) (“Minor”) must obtain consent from their parent or legal guardian to participate. By permitting an entrant to participate in the Sweepstakes such Minor’s parent or legal guardian represents and warrants that he or she has read, understands and agrees to the terms and conditions of these Official Rules on behalf of both the parent or legal guardian and the Minor. Directors, officers and employees of Sponsor and any of their respective affiliate companies, subsidiaries, agents, professional advisors, and advertising and promotional agencies, and each of their immediate families and persons living in their same household, are not eligible to win any prizes. Sweepstakes Period: The Sweepstakes begins on Wednesday, March 10, 2021 at 10:00 am and ends Wednesday, March 31, 2021 at 11:59 pm (all times in these Official Rules are Pacific Time). How to Enter: Limit three entries per person. To enter, you must (1) have a Nintendo Account (if you do not have a Nintendo Account you can register for free at https://my.nintendo.com/); (2) visit https://my.nintendo.com/reward_categories/sweepstake; (3) sign in to your Nintendo Account, and (4) redeem 10 Platinum Points per entry at the My Nintendo Mario and Yoshi Sweepstakes page (https://my.nintendo.com/rewards/b71c4e94797620c5). -

An Argument for Non-Formalist Level Generation in Super Mario Bros

``What is a Super Mario level anyway?'' An Argument For Non-Formalist Level Generation in Super Mario Bros. Tommy Thompson Anglia Ruskin University Cambridge, UK [email protected] ABSTRACT The video game series Super Mario Bros. has proven immensely popular in the field of artificial intelligence research within the last 10 years. Procedural content generation re- search in Super Mario continues to prove popular to this day. However much of this work is based largely on the notions of creating ‘Mario-like’ level designs, patterns or structures. In this paper, we argue for the need to diversify the generative systems used for level cre- ation within the Super Mario domain through the introduction of more aesthetic-driven and ‘non-formalist’ approaches towards game design. We assess the need for a broader approach to automated design of Mario artefacts and gameplay structures within the context of Super Mario Maker: a Super Mario Bros. level creation tool. By assessing a number of top-ranked levels established within the player community, we recognise a populist movement for more radical level design that the AI community should seek to embrace. Keywords Procedural content generation, level design, Super Mario Bros. INTRODUCTION Automated game design (AGD) is a field of research and development that focusses on the creation of entire games: ranging from traditional card and board games to that of video games. This is a immensely tasking yet creative field, with a large body of research typ- ically found within the procedural content generation (PCG) community: where emphasis is placed on creating specific assets such as the interactive space (levels/maps), weaponry, quests and story-lines. -

Super Mario World 2 Yoshis Island

V MORE MIYAMOTO MAGIC Video game players are cheering the arrival of the latest masterpiece from the world-famous design team of Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka. The terrific twosome, who brought you all the Super Mario Bros, and Zelda games, began by assembling a dream team of more than thirty ace artists, musicians and program- mers at Nintendo Company Ltd. in Japan. WRITER*: KENT MILLER After four years of intense effort, they’ve TERRY MUNfON delivered Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s MAR) AND tTRATEGIEt: WORK M0U5E JAPAN Island. After playing it once, you’ll never CAME STRATEGY: LEOTTOKAMOTO look at video games in quite the same way CONCERT AND DE9IGN: KARLDECKARD again! DAVE WHARTON The numbers alone are mind-boggling. PRODUCTION COORDINATOR: NANCY RAMIE More than 130 enemies patrol the game’s ELECTRONIC RRERRE9I: TIM ANDER10N 60-plus stages. There are dozens of secret : JAMEI CATECMI areas and bonus challenges. Miyamoto and DULY NOLAND Tezuka have pushed. the. Super FX2 graph- ics chip to the limi£,develbpihg a hew gramming technique called morphrnation. ... They’ve used it to prbduee enemies, that . grow, shrink, rotate and change shape. Some are even bigger than an entire screen! Yoshi’s Island also features ultra- realistic control. You can actually feel Yoshi slogging down muddy slopes and skidding over ice-covered ponds. Still, all these technical innovations never over- whelm the pure joy of playing the game. A rich palette and subtle shading give the backgrounds a magical effect. Whether flying over icy mountains or submarining through tropical lakes, you’ve never seen anyplace like Yoshi’s Island. -

Sts Case History

Shigeru Miyamoto: Game Designer A Case History by Patrick Kai Chen STS 145: History of Computer Game Design Professor H. Lowood 17 March 2002 Miyamoto, Yamauchi hired him as Nintendos first staff artist and also assigned t the 2000 ECTS show in London, Nintendo unveiled its him to be an apprentice in the planning A GameCube console for the first time in Europe. Following department (Kent 46). Though Miyamoto didnt have any programming experience, he some demo footage of the GameCubes capabilities, a middle- was not clueless about video game design. aged Japanese man with shoulder-length hair, one of Nintendos In college he had spent countless hours game designers, came onto the stage to unveil a video demo of playing in arcades, and for the first few years at Nintendo he had helped design characters the new Pokémon game, Meowths Party. As the music got for games like Sheriff. Moreover, pumping, surprisingly, so did the Japanese game designer. As Miyamoto had been designing games on his own time, but his ideas were repeatedly the crowd cheered him on with synchronous clapping, the rejected by Nintendo (Muldoon, The designer danced up a storm, demonstrating his hip moves and Legend, par. 3-5). As fate would have it his air guitar to boot. But who was this man? Who was this though, Miyamoto was soon given the opportunity of a lifetime. Nintendos first dancing fool of Nintendos? Why, who else could it be? As venture into America, the arcade game NintendoWeb so eloquently puts it, Shiggy was just getting jiggy. Radarscope, had flopped.