That's How You Write a Song

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telenor Sponsors Eurovision Song Contest

Telenor sponsors Eurovision Song Contest 125 million viewers expected to watch finale, broadcast live from Telenor Arena. On Saturday, 29 May, 125 million people across Europe and beyond will be watching the annual Eurovision Song Contest. Last year, Norwegian Alexander Rybak was crowned the winner, and Norway was deemed host of the 2010 event. Telenor Arena was selected as the best venue for the show, with the Telenor Group taking the reigns as the presenting partner. As the main sponsor, Telenor serves as the mobile phone partner and distributor of the show. Telenor is also working closely with the Norwegian National Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), the host broadcaster, to produce this live event. Part of the Telenor Group sponsorship is to ensure that the 2,500 journalists expected to attend are welcomed by a superior technical infrastructure. Telenor provides journalists with Internet access, technical support and free calling minutes upon their arrival at Telenor Arena. Learn more at Telenor Arenas webpage The finale airs on Saturday, May 29, at 21:00 CET. Check your local listings for channel information. For more information visit Eurovision's official site Telenor Group is one of the world's major mobile operators. We keep our customers connected in our markets across Scandinavia and Asia. Our more than 30,000 employees are committed to responsible business conduct and being our customers' favourite partner in digital life. Connecting the world has been Telenor's domain for more than 160 years, and we are driven by a singular vision: to empower societies. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 20/12/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 20/12/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Perfect - Ed Sheeran Grandma Got Run Over By A Reindeer - Elmo & All I Want For Christmas Is You - Mariah Carey Summer Nights - Grease Crazy - Patsy Cline Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Feliz Navidad - José Feliciano Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Michael Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Killing me Softly - The Fugees Don't Stop Believing - Journey Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Zombie - The Cranberries Baby, It's Cold Outside - Dean Martin Dancing Queen - ABBA Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree - Brenda Lee Girl Crush - Little Big Town Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi White Christmas - Bing Crosby Piano Man - Billy Joel Jackson - Johnny Cash Jingle Bell Rock - Bobby Helms Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Baby It's Cold Outside - Idina Menzel Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Let It Go - Idina Menzel I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Last Christmas - Wham! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Dean Martin You're A Mean One, Mr. Grinch - Thurl Ravenscroft Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Africa - Toto Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - Alan Jackson Shallow - A Star is Born My Way - Frank Sinatra I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor The Christmas Song - Nat King Cole Wannabe - Spice Girls It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas - Dean Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Please Come Home For Christmas - The Eagles Wagon Wheel - -

Vincono I Måneskin 6205 Boul

SAINT-LÉONARDSAINT-LÉONARD 559619 900 900$ $ AHUNTSICSAINT-LÉONARD 699218 900 800$ $ Istituto Nazionale Confederale di Assistenza • Magnifico bungalow nel cuore di St-Léonard • Duplex gemellato (31 X 34) • Mantenuto bene. Proprietario d'origine • Cucina e sala da pranzo a spazio aperto 514 721.7373 • Cucina rinnovata. Da non perdere! • Cortile bello e grande. Da non perdere! 1549 RUE JARRY EST, RE/MAX Alliance, Saint-Léonard, agence immobilière - 4865 rue Jarry Est - 514.329.0000 MONTRÉAL, QUÉBEC Vera Rosati PUBBLICITÀ PUBBLICITÀ IL GIORNALE ITALIANO 1° IN QUÉBEC E IN CANADA A pagina 13 LA VOIX DES ITALO-CANADIENS DEPUIS 1941 • CANADA’S FIRST ITALIAN NEWSPAPER SERIE A CHI PUÒ FERMARE L'INTER? Battuta anche l'Atalanta: ora Conte è Anno LXXX Nº 10 Montréal, 10 MARZO 2021 1.00$ + tx a +6 sul Milan e a+10 sulla Juventus Il Québec L'INTERVISTA AL FARMACISTA A pagina 10 è meno Michael Attia: “Proteggiamo rosso A pagina 3 noi stessi ed i nostri cari” Il Canada autorizza Dal 15 marzo, vaccinazioni CAPSULE Johnson & Johnson in 350 farmacie di Montréal ESPRESSO $ 'KIMBO' 99 PACCO DA 10 2 / PACCO SANREMO 2021 A pagina 12 Da X Factor all’Ariston: la band rock romana SUGHI PRONTI 'SAN MARZANO' $ si aggiudica la 71ª edizione 49 della kermesse canora 4 / L'UNO CREMA 'PAN DI STELLA' $ 280 GR 99 2 / L'UNO PASTA 'DE CECCO' CON L'ACQUISTO DI 2 PACCHI RICEVETE UNA GRATIS! SPECIALI VALIDI DAL 1O AL 31 MARZO VINCONO I MÅNESKIN 6205 BOUL. COUTURE SAINT-LÉONARD, QUÉBEC APERTO AL PUBBLICO: 514 325-2020 Lun-Ven 8-17 Sab 8-15 CON "ZITTI E BUONI" PUBBLICITÀ ROGUE -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

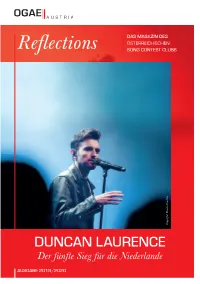

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

2019 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE Semi-Finals 14 & 16 May | Grand Final 18 May

2019 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE Semi-Finals 14 & 16 May | Grand Final 18 May ALBANIA ESTONIA LATVIA SAN MARINO Ktheju tokës Storm That Night Say Na Na Na Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by ARMENIA FINLAND LITHUANIA SERBIA Walking Out Look Away Run With The Lions Kruna Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AUSTRALIA FRANCE MALTA SLOVENIA Zero Gravity Roi Chameleon Sebi Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AUSTRIA GEORGIA MOLDOVA SPAIN Limits Keep on Going Stay La Venda Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by AZERBAIJAN GERMANY MONTENEGRO SWEDEN Truth Sister Heaven Too Late For Love Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BELARUS GREECE NORTH MACEDONIA SWITZERLAND Like It Better Love Proud She Got Me Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by BELGIUM HUNGARY NORWAY THE NETHERLANDS Wake Up Az én apám Spirit In The Sky Arcade Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by CROATIA ICELAND POLAND UNITED KINGDOM The Dream Hatrið mun sigra Fire of Love (Pali się) Bigger Than Us Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by CYPRUS IRELAND PORTUGAL Replay 22 Telemóveis Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by CZECH REPUBLIC ISRAEL ROMANIA Friend of a Friend Home On a Sunday Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by DENMARK ITALY RUSSIA Love Is Forever Soldi Scream Drawn by Drawn by Drawn by 2019 EUROVISION SWEEPSTAKE ALBANIA ARMENIA AUSTRALIA AUSTRIA AZERBAIJAN CZECH BELARUS BELGIUM CROATIA CYPRUS REPUBLIC DENMARK ESTONIA FINLAND FRANCE GEORGIA GERMANY GREECE HUNGARY ICELAND IRELAND ISRAEL ITALY LATVIA LITHUANIA MALTA NORTH MOLDOVA MONTENEGRO MACEDONIA NORWAY NORWAYPOLAND PORTUGAL ROMANIA RUSSIA SAN MARINO SANSERBIA MARINO SLOVENIA SPAIN SWEDEN SWITZERLAND THE NETHERLANDS UNITED KINGDOM. -

FROGS OPEN GRID YEAR SATURDAY SUNRISE at Frogland! Does It Warm Your Heart? the Fair, Old Place Is Offering Sincere and Happy NORMAL TEAM Welcome to Everybody

Start the Year Get the Spirit, Right, Frogs Freshmen THE \. y TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Vol. 24. I OUT WORTH, TKXAS, SKI'TEMMKK 23, 1925. No. 1 FROGS OPEN GRID YEAR SATURDAY SUNRISE at Frogland! Does it warm your heart? The fair, old place is offering sincere and happy NORMAL TEAM welcome to everybody. And every- PRESIDENTS RECEPTION EVENT OF WEEK body is more than glad to see the FACES BELL'S friendly face of the Alma Mater once more. To the new student that face ANNUAL FETE BEGINS THIRD YEAR NEW LINE COACH FAST CHARGES in merely handsome; the aspect of P ? the same face carries a deeper mean* WILL ATTRACT Madison Hell. I Fort Worth LCO Kdwin Kubale, formerly of Cen- Easl Texas Teachers' School wig for the old student. loot.M.i and baiketball product at tre college, Joined the athletic Furnishes First (.ante of Centre college, has started in on Ktaff of T. <\ I . this fall to Mir Purple's Football Season. FROM Canada to the Gulf, from LOCAL PEOPLE Itis third year as head roach ol IIU "resident Edward McShane \\ altt coed Jamei, n bo is BOH P ■ t it I ei Thunder,or voices booming Charleston to Frisco, students I he Horned Frogs. Saturday he r ;is University. Possessed of an have come (and are yet coming) like Invitations Extended to All will lead T. ('. I', into the first T11K session of l!tii. >-2(> has come upon us with a rush of sbnndance of line material, m a ■ a I .am' I'm pie clad warriors • Mm filings to a magnet. -

Schweizer Hitparade

Ed Sheeran 1 Bad Habits 14W WMS/WMS Måneskin Schweizer Hitparade 2 Beggin' 27W Top 100 Singles -/SME 25.07.2021 Shouse 3 Love Tonight 58W -/ING The Kid Laroi / Justin Bieber 4 Stay 62W -/SME RAF Camora 5 Zukunft NEU -/GRO 21 22 11W OneRepublic - Run -/UNI Olivia Rodrigo 22 17 16W Russ Millions x Tion Wayne - Body -/WMS 6 Good 4 U 23 NEU Jamule - Wenn ich geh -/UNI 4 10W -/UNI 24 19 7W Martin Garrix feat. Bono & The Edge - We Are The People -/SME 25 25 18W Justin Bieber feat. Daniel Caesar & Giveon - Peaches -/UNI 26 NEU RA F Camora - Realität -/GRO Pashanim 27 31 37W Tiësto - The Business -/WMS 7 Sommergewitter 28 32 20W Ofenbach feat. Lagique - Wasted Love -/WMS 34W 29 30 56W Master KG feat. Burna Boy & Nomcebo Zikode - Jerusalema (Remix) -/WMS -/UNI 30 39 11W Naps - La kiffance -/BED 31 42 15W Doja Cat feat. SZA - Kiss Me More -/SME Riton x Nightcrawlers feat. Mufasa & 32 28 10W Måneskin - Zitti e buoni -/SME 33 34 19W Imagine Dragons - Follow You -/UNI 8 Hypeman 34 45 5W Tinlicker & Helsloot - Because You Move Me -/KNM 8 23W Friday (Dopamine Re-Edit) 35 35 14W Tom Grennan - Little Bit Of Love -/SME -/SME 36 41 86W The Weeknd - Blinding Lights -/UNI 37 36 9W BTS - Butter SME/ORC Måneskin 38 43 2W Post Malone - Mötley Crew -/UNI 9 I Wanna Be Your Slave 39 40 13W Majestic x Boney M. - Rasputin -/SME 10 9W 40 29 10W Alvaro Soler - Magia -/UNI -/SME 41 NEU Pop Smoke feat. -

Artikel Babet Verstappen

REPORTAGE 44 Auteur Claudine Hogenboom Fotograaf Martijn Gijsbertsen Babet Verstappen, head of communications Eurovision Song Contest 2020 ‘Eurovisie Songfestival 2020 moet herkenbaar zijn én verrassen’ Na 44 jaar is het een Nederlander, Duncan De gloednieuwe projectruimte aan het Journaal- Laurence, gelukt het Eurovisie Songfestival plein in Hilversum dat bevolkt wordt door mensen weer eens te winnen en daaruit vloeit voort dat van NPO, NOS en AvroTros zal straks in zijn geheel Nederland het festijn in 2020 mag organiseren. verhuizen naar Ahoy. “We wisten natuurlijk meteen Babet Verstappen heeft er zin in. Sinds 1 sep- dat er heel veel op ons af zou komen. Gelukkig tember is ze Head of Communications Eurovisi- hadden we samen met NPO, NOS en AvroTros een on Song Contest 2020. “Het is toch fantastisch persbericht klaar, waarin we lieten weten dat we als dat ik mag bijdragen aan dit unieke evenement? driemanschap het Songfestival 2020 gaan organi- Mijn grootste uitdaging is dat we met een pro- seren. Dit is uniek voor Nederland en ik ben er trots fessioneel en positief ingesteld team een Euro- op dat we dit zo samen kunnen doen.” visie Songfestival kunnen maken waarin Neder- land zich herkent en dat Europa positief verrast. Betrokkenheid En dit alles in slechts acht maanden tijd.” De eerste dagen na de overwinning kwamen de eerste vragen: wanneer kunnen we kaartjes kopen, “Een week of vier voor het Songfestival was Duncan Laurence nog steeds favoriet bij de book- makers en dat bleef redelijk stabiel. Toen ben ik voor de NOS naar Israël vertrokken. Na de punten- Tip telling van de vakjury dacht ik, hij gaat het niet red- Bekijk het filmpje waarin Rotterdam voor het den. -

She Smiles Sadly*.•

Number 5 Volume XXVIII. SEATTLE, WASHINGTON, FEBRUARY 4, 1933 SHE SMILES SADLY*.• • Kwan - Yin, Chinese Goddess of Mercy, some times called the Goddess of Peace, has reason these days for that sardonic expression, although the mocking smile is by no means a new one; she has worn it since the Wei Dynasty, Fifth Century A. D. The Goddess is the property of the Bos ton Museum of Art.— Courtesy The Art Digest. Featured This Week: Stuffed Zoos, by Dr. Herbert H. Gowen "Two Can Play"—, by Mack Mathews Editorials: (Up Hill and Down, Amateur Orchestra In Dissent, by George Pampel Starts, C's and R's, France Buys American) A Woman's Span (A Lyrical Sequence), by Helen Maring two THE TOWN CRIER FEBRUARY 4, 1933 By John Locke Worcester. Illus Stage trated with lantern slides. Puget "In Abraham's Bosom'' (Repertory Sound Academy of Science. Gug Playhouse)—Paul Green's Pulit AROUND THE TOWN genheim Hall. Wednesday, Febru zer prize drama produced by Rep ary 22, 8:15 p. m. ertory Company, with cast of Se attle negro actors. Direction Flor By MARGARET CALLAHAN Radio Highlights . , ence Bean James. A negro chorus sings spirituals. Wednesdays and Young People's Symphony Concert Fridays for limited run. 8:30 p.m. "Camille" (Repertory Playhouse) — Spanish ballroom, The Olympic. —New York Philharmonic, under direction of Bruno Walter. 8:30- "Funny Man" (Repertory Play All-University drama. February February 7, 8:30 p. m. 16 and 18, 8:30 p. m. Violin, piano trio—Jean Margaret 9:15 a. m. Saturday. KOL. house)—Comedy of old time Blue Danube—Viennese music un vaudeville life by Felix von Bres- Crow and Nora Crow Winkler, violinists, and Helen Louise Oles, der direction Dr. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat.