The Uses of Maritime History in and for the Navy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

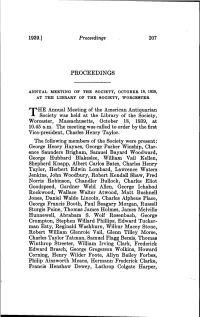

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

Navy Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program

Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 14, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R41129 Navy Columbia (SSBN-826) Class Ballistic Missile Submarine Program Summary The Navy’s Columbia (SSBN-826) class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program is a program to design and build a class of 12 new SSBNs to replace the Navy’s current force of 14 aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Since 2013, the Navy has consistently identified the Columbia-class program as the Navy’s top priority program. The Navy procured the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021 and wants to procure the second boat in the class in FY2024. The Navy’s proposed FY2022 budget requests $3,003.0 (i.e., $3.0 billion) in procurement funding for the first Columbia-class boat and $1,644.0 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in advance procurement (AP) funding for the second boat, for a combined FY2022 procurement and AP funding request of $4,647.0 million (i.e., about $4.6 billion). The Navy’s FY2022 budget submission estimates the procurement cost of the first Columbia- class boat at $15,030.5 million (i.e., about $15.0 billion) in then-year dollars, including $6,557.6 million (i.e., about $6.60 billion) in costs for plans, meaning (essentially) the detail design/nonrecurring engineering (DD/NRE) costs for the Columbia class. (It is a long-standing Navy budgetary practice to incorporate the DD/NRE costs for a new class of ship into the total procurement cost of the first ship in the class.) Excluding costs for plans, the estimated hands-on construction cost of the first ship is $8,473.0 million (i.e., about $8.5 billion). -

Britain and the Royal Navy by Jeremy Black

A Post-Imperial Power? Britain and the Royal Navy by Jeremy Black Jeremy Black ([email protected]) is professor of history at University of Exeter and an FPRI senior fellow. His most recent books include Rethinking Military History (Routledge, 2004) and The British Seaborne Empire (Yale University Press, 2004), on which this article is based. or a century and a half, from the Napoleonic Wars to World War II, the British Empire was the greatest power in the world. At the core of that F power was the Royal Navy, the greatest and most advanced naval force in the world. For decades, the distinctive nature, the power and the glory, of the empire and the Royal Navy shaped the character and provided the identity of the British nation. Today, the British Empire seems to be only a memory, and even the Royal Navy sometimes can appear to be only an auxiliary of the U.S. Navy. The British nation itself may be dissolving into its preexisting and fundamental English, Scottish, and even Welsh parts. But British power and the Royal Navy, and particularly that navy’s power projection, still figure in world affairs. Properly understood, they could also continue to provide an important component of British national identity. The Distinctive Maritime Character of the British Empire The relationship between Britain and its empire always differed from that of other European states with theirs, for a number of reasons. First, the limited authority and power of government within Britain greatly affected the character of British imperialism, especially, but not only, in the case of colonies that received a large number of British settlers. -

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

“Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 2, folder “Bicentennial Speeches (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 2 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR ROBERT ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: PRE-ADVANCE REPORT ON THE PRESIDENT'S ADDRESS AT THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES Attached is some background information regarding the speech the President will make on July 2, 1976 at the National Archives. ***************************************************************** TAB A The Event and the Site TAB B Statement by President Truman dedicating the Shrine for the Delcaration, Constitution, and Bill of Rights, December 15, 1952. r' / ' ' ' • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON June 28, 1976 MEMORANDUM FOR BOB ORBEN VIA: GWEN ANDERSON FROM: CHARLES MC CALL SUBJECT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES ADDENDUM Since the pre-advance visit to the National Archives, the arrangements have been changed so that the principal speakers will make their addresses inside the building . -

Age of Exploration Flyer

POSTER INSIDE POSTER Age of Exploration A DIGITAL RESOURCE Introduction Explore five centuries of journeys across the globe, scientific discoveries, the expansion of European colonialism, new trade routes, and conflict over territories. Overview This impressive multi-archive collection focuses on “This remarkable collection European, maritime exploration from the earliest voyages of Vasco da Gama and Christopher provides the documentary Columbus, through the age of discovery, the search base to interpret some of the for the ‘New World’, the establishment of European settlements on every continent, to the eventual major movements of the age discovery of the Northwest and Northeast Passages, of exploration. The variety and the race for the Poles. of the sources made available Bringing together material from twelve archives from opens perspectives that should around the world, this collection includes documents challenge students and bring the relating to major events in European maritime history from the voyages of James Cook to the search for period to life. It is a collection John Franklin’s doomed mission to the Northwest that promotes both historical Passage. It contains a host of additional features for analysis and imagination.” teaching, such as an interactive map which presents an in-depth visualisation of over 50 of these Emeritus Professor John Gascoigne influential voyages. University of New South Wales Highlights Material Types • Captain Cook’s secret instructions, ships’ logs and • Le Livre des merveilles by Marco Polo including the • Diaries, journals and ships’ logbooks journals from three voyages of James Cook, written illuminations of Maître d’Egerton – this illuminated Printed and manuscript books by various crew members and Cook himself which relate manuscript compendium dates from c.1410-1412 and • to early British Pacific exploration and the search for is comprised of geographical works and accounts of • Correspondence, notes and ephemera Terra Australis. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

248 Part 3—Navy Activity Address Numbers

Ch. II, App. G 48 CFR Ch. 2 (10±1±96 Edition) PART 3ÐNAVY ACTIVITY ADDRESS Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe, (London, U.K.), FPO AE 09499 NUMBERS N00062Ð8A*, L9*, R0*, 8A0±9 Chief of Naval Education and Training, * An asterisk indicates a two-digit code of Code 013, NAS, Pensacola, FL 32508±5100 a major command, which is shared with sub- N00063ÐNT*, NTZ ordinate activities. Such subordinate activi- Naval Computer and Telecommunications ties will indicate the Unit Identification Command, 4401 Massachusetts Avenue Code of the major command in parentheses, NW., Washington, DC 20394±5290 e.g. (MAJ00011). N00065ÐS0*, S0Z N00011ÐLB*, LBZ Naval Oceanography Command, Stennis Chief of Naval Operations, Washington, DC Space Center, Bay St. Louis, MS 39529± 20350±2000 5000 N00012ÐHX*, V8*, V8Y N00069Ð8Q*, 8QZ Assistant for Administration, Under Sec- Naval Security Group HQ, 3801 Nebraska retary of the Navy, Washington, DC 20350 Avenue NW., Washington, DC 20390±0008 N00013ÐMR N00070ÐLP*, V5*, 4L*, LPZ Judge Advocate General, Navy Depart- Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, ment, 200 Stovall Street, Alexandria, VA NAVBASE, Pearl Harbor, HI 96860±7000 22332 N00072Ð9T*, LC*, 9TZ N00014ÐEE*, EE0±9 Commander, Naval Reserve Force, Code 17, Office of Naval Research, Arlington, VA New Orleans, LA 70146 22217 N00074ÐQH*, QHZ N00015ÐL0*, L0Z Naval Intelligence Command HQ, Naval Special Warfare Command, (Suitland, MD), 4600 Silver Hill Road, NAVPHIBASE Coronado, San Diego, CA Washington, DC 20389 92155 N00018ÐMC*, MD*, J5*, QA*, MCZ N00101Ð3R Bureau -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS THE FEDERAL LIBRARY AND BICENTENNIAL INFORMATION CENTER 1800 - 2000 COMMITTEE American Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology 1780 Military garrison at West Point establishes library by assessing officers at the rate of one day’s pay per month to purchase books—arguably the first federal library since it existed when the country was founded (predecessor to U.S. Military Academy Library) 1789 First official federal library established at the Department of State 1795 War Department Library established in Philadelphia as a general historical military library by Henry Knox, the first Secretary of War 1800 The Navy Department Library established on March 31 by direction of President John Adams to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert 1800 Library of Congress (LoC) founded on April 24 1800 War Department Library collections destroyed in fire at War Office Building on November 8, soon after relocation to Washington 1802 The President and Vice President authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Supreme Court Justices authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Congress appropriates $50,000 for the procurement of instruments and books for Coast Survey 1814 British burn both State Department Library and LoC collections during War of 1812 1815 Congress purchases Thomas Jefferson’s private library to replace LoC collections and opens collections to the general public 1817 Earliest documentation of book purchasing for Department of Treasury library 1820 Army Surgeon General James Lovell establishes office collection of books -

Command: a Historical Perspective

2020, VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 AN OCCASIONAL PAPER SERIES COMMAND: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Rear Admiral (Ret) James Goldrick Royal Austrailian Navy CENTER FOR CHARACTER & LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT EDITORIAL STAFF: EDITORIAL BOARD: Dr. Mark Anarumo, Dr. David Altman, Center for Creative Managing Editor, Colonel, USAF Leadership Dr. Douglas Lindsay, Dr. Marvin Berkowitz, University of Missouri- Editor in Chief, USAF (Ret) St. Louis Dr. John Abbatiello, Dr. Dana Born, Harvard University Book Review Editor, USAF (Ret) (Brig Gen, USAF, Retired) Dr. David Day, Claremont McKenna College Ms. Julie Imada, Editor & CCLD Strategic Dr. Shannon French, Case Western Communications Chief Dr. William Gardner, Texas Tech University JCLD is published at the United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Mr. Chad Hennings, Hennings Management Colorado. Articles in JCLD may be Corp reproduced in whole or in part without permission. A standard source credit line Mr. Max James, American Kiosk is required for each reprint or citation. Management For information about the Journal of Dr. Barbara Kellerman, Harvard University Character and Leadership Development or the U.S. Air Force Academy’s Center Dr. Robert Kelley, Carnegie Mellon for Character and Leadership University Development or to be added to the Association of Graduates Journal’s electronic subscription list, Ms. Cathy McClain, (Colonel, USAF, Retired) contact us at: Dr. Michael Mumford, University of [email protected] Oklahoma Phone: 719-333-4904 Dr. Gary Packard, United States Air Force Academy (Colonel, USAF) The Journal of Character & Leadership Development Dr. George Reed, University of Colorado at The Center for Character & Leadership Colorado Springs (Colonel, USA, Retired) Development Rice University U.S.