The Doctrine of Resurrection in the Book of Mormon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events

Critique of a Limited Geography for Book of Mormon Events Earl M. Wunderli DURING THE PAST FEW DECADES, a number of LDS scholars have developed various "limited geography" models of where the events of the Book of Mormon occurred. These models contrast with the traditional western hemisphere model, which is still the most familiar to Book of Mormon readers. Of the various models, the only one to have gained a following is that of John Sorenson, now emeritus professor of anthropology at Brigham Young University. His model puts all the events of the Book of Mormon essentially into southern Mexico and southern Guatemala with the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the "narrow neck" described in the LDS scripture.1 Under this model, the Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites were relatively small colonies living concurrently with other peoples in- habiting the rest of the hemisphere. Scholars have challenged Sorenson's model based on archaeological and other external evidence, but lay people like me are caught in the crossfire between the experts.2 We, however, can examine Sorenson's model based on what the Book of Mormon itself says. One advantage of 1. John L. Sorenson, "Digging into the Book of Mormon," Ensign, September 1984, 26- 37; October 1984, 12-23, reprinted by the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS); An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: De- seret Book Company, and Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1985); The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1990); "The Book of Mormon as a Mesoameri- can Record," in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. -

The Name Mormon in Reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages

The Name Mormon in reformed Egyptian, Sumerian, and Mesoamerican Languages by Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG May 1, 2017 Blind third party peer review performed by After obtaining the golden plates, Joseph Smith stated that once he moved to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in the winter of 1827, he “commenced copying the characters of[f] the plates.” He stated: I copyed a considerable number of them and by means of the Urim and Thummin I translated some of them.1 In the mid 1830s, Oliver Cowdery and Frederick G. Williams recorded four characters that had been copied from the plates and Joseph Smith’s translations of those characters; one set of two characters was translated together as “The Book of Mormon” and the other set of two characters was translated as “The interpreters of languages” (see figures 1 and 2). Both of these phrases can be found in the original script of the current Title Page of the Book of Mormon. It clearly includes “Book of Mormon,” mentions “interpretation,” and infers the language of the Book of Mormon. It is reasonable therefore to assume that these characters came from the Title Page. Figure 1. Book of Mormon characters copied by Oliver Cowdery, circa 1835–1836 1 Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers: Histories, Volume 1 (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 1:240. 1 Figure 2. Close-up of the Book of Mormon characters copied by Fredrick G. Williams, circa February 27, 1836 (MacKay et al. 2013, 137) 2 In a 2015 publication, I successfully translated all four of these characters from known hieratic and Demotic Egyptian glyphs.3 The name Mormon (second glyph of the first set of two) in the “reformed Egyptian” is an interesting case study. -

Mosiah the Lack of a Preface for the Book of Mosiah in the Present Book

Book of Mormon Commentary Mosiah 1 Mosiah The lack of a preface for the book of Mosiah in the present Book of Mormon is probably because the text takes 1 up the Mosiah account some time after its original beginning. The original manuscript of the Book of Mormon, written in Oliver Cowdery’s hand, has no title for the Book of Mosiah. It was inked in later, prior to sending it to the printer for typesetting. The first part of Mormon’s abridgment of Mosiah’s record…was evidently on the 116 pages lost by Martin Harris. John A. Tvedtnes, Rediscovering the Book of Mormon, ed. By John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne [Salt Lake City: 1991], 33 Note that the main story in the book of Mosiah is told in the third person rather than in the first person as was the 2 custom in the earlier books of the Book of Mormon. The reason for this is that someone else is now telling the story and that “someone else” is Mormon. With the beginning of the book of Mosiah we start our study of Mormon’s abridgment of various books that had been written on the large plates of Nephi (3 Nephi 5:8-12). The book of Mosiah and the five books that follow—Alma, Helaman, 3 Nephi, 4 Nephi, and Mormon—were all abridged or condensed by Mormon from the large plates of Nephi, and these abridged versions were written by Mormon on the plates that bear his name, the plates of Mormon. These are the same plates that were given to Joseph Smith by the angel Moroni on September 22, 1827. -

“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton's Dissent

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2020-8 “They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent Dan Belnap Brigham Young University, [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Dan and Belnap, Daniel L., "“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent" (2020). Faculty Publications. 4479. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4479 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ILLUMINATING THE RECORDS Edited by Daniel L. Belnap Published by the Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, in cooper- ation with Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City. Visit us at rsc.byu.edu. © 2020 by Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. DESERET BOOK is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company. Visit us at DeseretBook.com. Any uses of this material beyond those allowed by the exemptions in US copyright law, such as section 107, “Fair Use,” and section 108, “Library Copying,” require the written permission of the publisher, Religious Studies Center, 185 HGB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of Brigham Young University or the Religious Studies Center. -

How Were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related?

KnoWhy #109 May 27, 2016 Battle with Zeniff . Artwork by James Fullmer How were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related? “Now the people of Amlici were distinguished by the name of Amlici, being called Amlicites” Alma 2:11 The Know Only five years into the reign of the judges, the pres- with no introduction or explanation as to their ori- sure to reestablish a king was already mounting. A gins (Alma 21:2–4, 16).3 Later they are included in a “certain man, being called Amlici,” emerged, and list of Nephite dissenters (Alma 43:13), but this is all he drew “away much people after him” who “be- that is said of their origins. gan to endeavor to establish Amlici to be a king over the people” (Alma 2:1–2). When “the voice of The complete disappearance of the Amlicites, com- people” failed to grant kingship to Amlici,1 his fol- bined with the mysterious mention of the similarly lowers anointed him king anyway, and they broke named Amalekites, has led some scholars to con- away from the Nephites, becoming Amlicites (Alma clude that the two groups are one and the same.4 As 2:7–11). Christopher Conkling observed, “One group is in- troduced as if it will have ongoing importance. The The rebellion of the Amlicites led to armed conflict other is first mentioned as if its identity has already with the Nephites (Alma 2:10–20), and then an al- been established.”5 legiance with the Lamanites, followed by further bloodshed, wherein Amlici was slain in one-on-one Royal Skousen has found evidence from the original combat with Alma (Alma 2:21–38). -

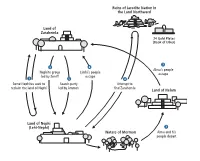

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 51 | Issue 4 Article 10 12-1-2012 When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M. Lyon Kent R. Minson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Lyon, Jack M. and Minson, Kent R. (2012) "When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 51 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol51/iss4/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Lyon and Minson: When Pages Collide: Dissecting the Words of Mormon Page from the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon, showing on line 3 the beginning of the book of Mosiah. Courtesy Community of Christ, Independence, Missouri. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2012 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 51, Iss. 4 [2012], Art. 10 When Pages Collide Dissecting the Words of Mormon Jack M. Lyon and Kent R. Minson erses 12–18 of the Words of Mormon have always been a bit of a puzzle. VFor stylistic and other reasons, they do not really fit with verses 1–11, so commentators have tried to explain their presence as a sort of “bridge” or “transition” that Mormon wrote to connect the record of the small plates with his abridgment from the large plates.1 This paper proposes a different explanation: Rather than being a bridge into the book of Mosiah, these verses were originally part of the book of Mosiah and should be included with it. -

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell

Christmas in Zarahemla Written by Mary Ashworth & Tamara Fackrell Narrator: From the dawn of Creation, mankind looked forward to the central event of the Holy Scriptures—the coming of the promised Messiah—the KING OF KINGS. The dispensations of Adam and Enoch, Noah, Abraham and Moses all kept and treasured this most precious message. A Redeemer would come to save the world from sin and error. The children of the covenant, those descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, made their way to Egypt in the time of famine, to find their brother Joseph in a position of power. There they flourished, and then became enslaved. At last the 400-year sojourn in Egypt came to an end with the mighty Proclamation of Moses, “Let my people go.” The Red Sea parted for these children of the covenant and they gave thanks for their escape. Arriving in the Promised Land, they built a Temple to the Most High God. For a thousand years they kept alive the treasured Word. The Law of Moses was their constant reminder of the coming of the Redeemer. Voice of Sariah: The prophet Isaiah Spoke: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son and shall call his name Immanuel. For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. “(Isaiah 9:6) Choir: O Little Town of Bethlehem Narrator: The beautiful Temple of Solomon was destroyed by the invading Babylonians in 587 B.C. -

“Converted Unto the Lord”

HIDDEN LDS/JEWISH INSIGHTS - Book of Mormon Gospel Doctrine Supplement #26 by Daniel Rona Summary Handout =========================================================================================================== “Converted unto the Lord” Lesson 26 Summary Alma 23– 29 =========================================================================================================== Scripture Religious freedom is proclaimed—The Lamanites in seven lands and cities are converted—They call themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies and Summary: are freed from the curse—The Amalekites and the Amulonites reject the truth. The Lamanites come against the people of God—The Anti-Nephi-Lehies rejoice in Christ and are visited by angels—They choose to suffer death rather than to defend themselves—More Lamanites are converted. Lamanite aggressions spread—The seed of the priests of Noah perish as Abinadi prophesied—Many Lamanites are converted and join the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi—They believe in Christ and keep the law of Moses. Ammon glories in the Lord—The faithful are strengthened by the Lord and are given knowledge—By faith men may bring thousands of souls unto repentance—God has all power and comprehendeth all things. The Lord commands Ammon to lead the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi to safety—Upon meeting Alma, Ammon’s joy exhausts his strength—The Nephites give them the land of Jershon— They are called the people of Ammon. [Between 90 and 77 B.C.] The Lamanites are defeated in a tremendous battle—Tens of thousands are slain—The wicked are consigned to a state of endless woe; the righteous attain a never-ending happiness. [About 76 B.C.] Alma desires to cry repentance with angelic zeal—The Lord grants teachers for all nations—Alma glories in the Lord’s work and in the success of Ammon and his brethren. -

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA

EVIDENCE of the NEHOR RELIGION in MESOAMERICA Jerry D. Grover Jr., PE, PG Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica Evidence of the Nehor Religion in Mesoamerica by Jerry D. Grover, Jr. PE, PG Jerry D. Grover, Jr., is a licensed Professional Structural and Civil Engineer and a licensed Professional Geologist. He has an undergraduate degree in Geological Engineering from BYU and a Master’s Degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Utah. He speaks Italian and Chinese and has worked with his wife as a freelance translator over the past 25 years. He has provided geotechnical and civil engineering design for many private and public works projects. He took a 12-year hiatus from the sciences and served as a Utah County Commissioner from 1995 to 2007. He is currently employed as the site engineer for the remediation and redevelopment of the 1750-acre Geneva Steel site in Vineyard, Utah. He has published numerous scientific and linguistic books centering on the Book of Mormon, all of which are available for free in electronic format at www.bmslr.org. Acknowledgments: This book is dedicated to my gregarious daughter, Shirley Grover Calderon, and her wonderful husband Marvin Calderon and his family who are of Mayan descent. Thanks are due to Sandra Thorne for her excellent editing, and to Don Bradley and Dr. Allen Christenson for their thorough reviews and comments. Peer Review: This book has undergone third-party blind review and third-party open review without distinction as to religious affiliation. As with all of my works, it will be available for free in electronic format on the open web, so hopefully there will be ongoing peer review in the form of book reviews, etc. -

The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 6 Number 2 Article 18 7-31-1997 The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi David E. Sloan Van Cott, Bagley and Cornwall, Salt Lake City Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sloan, David E. (1997) "The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 6 : No. 2 , Article 18. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol6/iss2/18 This Notes and Communications is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Notes and Communications: The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi Author(s) David E. Sloan Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 6/2 (1997): 269–72. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon consistently use such phrases as “Book of Lehi,” “plates of Lehi,” and “account of Nephi” in distinct ways. NOTES AND COMMUNICATIONS The Book of Lehi and the Plates of Lehi David E. Sloan In the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith wrote that the lost 116 pages included his translation of "the Book of Lehi, which was an account abridged from the plates of Lehi, by the hand of Mormon." However, in Doctrine and Covenants 10:44, the Lord told Joseph that the lost pages contained "an abridgment of the account of Nephi." Some critics have argued that these statements are contradictory and therefore somehow provide evidence that Joseph Smith was not a prophet.