The Ballad of Baby Doe: Central City Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer Cotillion Suite (1952) ................................................ (14:06) 5. I Grand March .......................................... (2:08) 6. II Polka ..................................................... (1:29) 7. III Waltz ................................................... (3:35) 8. IV Gallop .................................................. (2:01) 9. V Cake Walk ............................................ (1:56) 10. VI Quickstep ............................................ (2:57) The Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra; Alfredo Antonini, conductor Symphony in A (1945) .............................................. (19:15) 11. I Andante con moto; Allegro giusto ....... (7:18) 12. II Andante quieto semplice .................... (5:39) 13. III Allegretto ............................................ (2:26) 14. IV Allegro con spirito .............................. (3:52) Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra; William Strickland, conductor Marion Bauer (1887-1955) Prelude & Fugue for flute & strings (1948) ................ (7:27) 15. Prelude ..................................................... (5:45) 16. Fugue ........................................................ (1:42) Suite for String Orchestra (1955) ................... (14:47) 17. I Prelude ................................................... (6:50) Douglas Moore (1893-1969) 18. II Interlude ................................................ (4:41) Farm Journal (1948) ................................................. (14:20) 19. III Finale: Fugue -

CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC for the Degree of MASTER of MUSIC By

ol 0002 -T-E CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA IN TVVENTIETH CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By U3arney C. Tiller, Jr., B. M., B. A. Denton, Texas January, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . II. THE HISTORY OF THE CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA . 5 III. ANALYSES OF SEVENTEEN CHACONNES AND PASSACAGLIAS FROM THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. 34 IV. CONCLUSIONS . 116 APPENDIX . 139 BIBLIOGRAPHY. * . * . * . .160 iii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Grouping of Variations According to Charac- teristics of Construction in the Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .. 40 TI. Thematic Treatment in the Chaconne from the Prelude, Toccata and Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .*0 . 41 III. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passacaglia and Fugue by Roland Diggle. 45 IV. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Moto Continuo and Passacglia by 'Herbert F. V. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia by Alan Gray . $4 VI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia b Robert . .*. -...... .... $8 Groves * - 8 VII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia by Ellis B. Kohs . 64 VIII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passaglia in A Minor by C. S. Lang . * . 73 IX. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passaca a andin D Minor by Gardner Read * . - - *. -#. *. 85 X. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacgland ugue by Healey Willan . 104 XI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacaglia and F by Searle Wright . -

American Opera 20Th Century Style at USD November 16 and 17 Office of Publicnfor I Mation

University of San Diego Digital USD News Releases USD News 1973-10-31 American Opera 20th Century Style at USD November 16 and 17 Office of Publicnfor I mation Follow this and additional works at: http://digital.sandiego.edu/newsreleases Digital USD Citation Office of Public Information, "American Opera 20th Century Style at USD November 16 and 17" (1973). News Releases. 872. http://digital.sandiego.edu/newsreleases/872 This Press Release is brought to you for free and open access by the USD News at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in News Releases by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .NEWS RELEASE UNIVERSITY OF .SAN DIEGO OFFICE OF PUBLIC INFORMATION CONTACT: SARAS. FINN ill TELEPHONE : 714-291-6480 / EXT. 354 SD ADDRESS: RM. 266 DE SALES HALL, ALCALA PARK, SAN DIEGO, CA 92110 AMERICAN OPERA 20TH CENTURY STYLE AT USD NOVEMBER 16 AND 1 7 IMMEDIATE RELEASE San Diego, California "American Opera Twentieth Century Style", under the direction of pianist Ilana Mysior, will be presented on November 16 and 17 in the University of San Diego's Camino Theatre. The 8:15 p.m. per formances are open to the public. The West Coast premi ere of "Captain Lovelock", a contemporary work in one act by John Duke, will highlight the three-part program. Duke, a teacher at Smith College, has set his story of a middle aged widow and her daughters at the turn of the century. The romantic comedy weaves around a mother who has been reawakened in her desire to remarry only to be spoofed by her daughters . -

Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor Madalyn W

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-12-2013 Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor Madalyn W. Mentor Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mentor, Madalyn W., "Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor" (2013). Research Papers. Paper 393. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/393 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR by Madalyn Mentor B.A., Berea College, 2011 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music School of Music Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2013 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR By Madalyn Mentor A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Vocal Performance Approved by: Dr. Jeanine Wagner, Chair Dr. Susan Davenport Dr. Paul Transue Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 12, 2013 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF MADALYN MENTOR, for the Master of Music degree in VOCAL PERFORMANCE, presented on April 12, 2013, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Merola Opera Program: Schwabacher Summer Concert

Merola Opera Program Schwabacher Summer Concert 2017 WHEN: VENUE Sunday, Bing JuLy 9, 2017 ConCert HaLL 2:30 PM Photo: Kristen Loken Program (Each excerpt’s cast listed by order of appearance) Jules Massenet: Thaïs (1894) Giacomo Puccini: Le Villi (1884) from act 2 “La tregenda” “Ah, je suis seule…Dis-moi que je suis belle…Étranger, te voilà.” orchestra thaïs—Mathilda edge Douglas Moore: The Ballad of Baby Doe (1956) athanaël—thomas glass act 1, Scenes 2 and 3 nicias—andres acosta “What a lovely evening…Willow where we met together… Warm as the autumn light…Now where do you suppose that Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria rusticana (1890) he can be?...I send these lacy nothings.” “Tu qui, Santuzza…Fior di giaggiolo… Ah, lo vedi, che hai tu detto.” Baby doe—Kendra Berentsen Horace tabor—dimitri Katotakis turiddu—Xingwa Hao augusta tabor—alice Chung Santuzza—alice Chung Kate—Mathilda edge Lola—alexandra razskazoff Meg—Felicia Moore Samantha—alexandra razskazoff Kurt Weill: Street Scene (1947) townspeople—Mathilda edge, act 1, Scene 7 (“ice Cream Sextet”) Felicia Moore, alexandra razskazoff, andres acosta, “First time I come to da America…” thomas glass Lippo—andres acosta Gaetano Donizetti: Lucrezia Borgia (1833) Mrs. Jones—alexandra razskazoff from act 1 Mrs. Fiorentino—Kendra Berentsen “Tranquillo ei posa…Com’è bello…Ciel! Che vegg’io?...Di Mrs. olsen—alice Chung pescatore ignobile.” Henry—Xingwa Hao Mr. Jones—thomas glass Lucrezia—alexandra razskazoff Mr. olsen—dimitri Katotakis gubetta—thomas glass duke—dimitri Katotakis rustighello—Xingwa Hao anne Manson, conductor gennaro—andres acosta david Lefkowich, director Carl Maria von Weber: Der Freischütz (1821) from act 2 “Wie nahte mir der Schlummer…Leise, leise, fromme Weise… Wie? Was? Entsetzen!” agathe—Felicia Moore Max—Xingwa Hao Ännchen—Kendra Berentsen INTERMISSION PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

Hansel and Gretel

LEON WILSON CLARK OPERA SERIES SHEPHERD SCHOOL OPERA and the SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA present HANSEL AND GRETEL An opera in three acts by Engelbert Humperdinck Libretto by Adelheid Wette Richard Bado, conductor Debra Dich son, stage director and choreographer October 26, 28, 30 and November 1 7:30 p.m. Wortham Opera Theatre Cel e b ratin . g1; 1975 -2005 1/7 Years THE SHEPHERD SCHOOL t ~ IC RICE UNIVERSITY CAST (in order of vocal appearance) Wednesday, October 26; Friday, October 28; Sunday, October 30 Gretel. Angela Mortellaro Hansel. Kira Austin-Young Mother . Valerie Rogotzke Father. Colm Estridge Sandman . Audrey Walstrom Dew Fairy Hannah Nelson Witch . James Hall Tuesday, November 1 Gretel. Hannah Nelson Hansel . Audrey Walstrom Mother . Valerie Rogotzke Father. Raines Taylor Sandman. Kelly Duerr Dew Fairy Amanda Conley Witch . James Hall Angels and Gingerbread children: Rebecca Henry, Andrea Leyton Mange, Catherine Ott-Holland, Quinn Shadko, Lauren Snouffer, Ryan Stickney, Meghan Tarkington, Emily Vacek Demons: Grace Field, Katina Mitchell, Keith Stonum, Dan Williamson Members of the SHEPHERD SCHOOL CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Larry Rachleff, music director Violin I Cello Trumpet Kristi Helberg, Madeleine Kabat John Williamson concertmaster Victoria Bass Jonathan Brandt Rachelle Hunt Cristian Macelaru Double Bass Trombone Kristiana Matthes Jordan Scapinello, Colin Wise principal Pei-Ju Wu Harp Edward Botsford Kaoru Suzuki Earecka Tregenza Violin II Flute Timpani Steven Zander, Leslie Richmond Evy Pinto principal Oboe 'v Jessica -

The Ballad of Baby Doe Will Be Heard This Week in a Cleveland Opera Production

Baby Doe Is An Opera Rich In Americana by Robert Finn, Music Critic The Cleveland Plain Dealer Sunday, March 29, 1992 A good many European musicians-most prominently Antonin Dvorak-have wondered publicly why American composers did not draw more inspiration from this country's rich store of legend and history. One composer who heeded that advice was former Clevelander Douglas Moore, whose popular opera The Ballad of Baby Doe will be heard this week in a Cleveland Opera production. In addition to making this opera out of the true story of Horace Tabor and young Elizabeth (Baby Doe) McCourt, Moore also composed operas about Daniel Webster and Carrie Nation. His most popular orchestra piece is called The Pageant of P.T. Barnum. Moore wrote Baby Doe on a commission from the Koussevitzky Music Foundation in the mid-l950s. It was premiered in 1956 in Central City, Colorado, and was taken up the next season by the New York City Opera in a celebrated production starring Beverly Sills. The story is a conventional love triangle in the distinctively American setting of 1880s Colorado. Horace Tabor, a venturesome Vermonter who struck it rich in the western gold fields, deserts his somewhat formidable wife for the charms of the young and flirtatious Baby Doe. Eventually the two are married, scandal ensues and Tabor is impoverished by the abandonment of silver as the standard for U.S. currency. The last scene is a flashback and flash-forward, showing Baby Doe, now a white-haired old woman, freezing to death years later at the entrance to the played-out silver mine. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

Music Festival Will Be Presented on Successive

NEWS RELEASE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Washington, D. C. Republic 7-U215, extension 282 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TWELFTH ANNUAL AMERICAN MUSIC FESTIVAL AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Washington, April 8, 19"?£s David E0 Finley, Director of the National Gallery of art, announced today that the Gallery's Twelfth American Music Festival will be presented on successive Sunday evenings from April ?l|th through May 29th Six programs will be played, including orchestral, chamber, piano, and choral music. The series is under the general direction of Richard Bales, who will conduct the two orchestral concerts. These concerts will be given in the East Garden Court, beginning at Q; 00 P. Mo There is no admission charge, and tickets and reservations are not required. Station WGMS and the Good Music Network will broadcast these programs in their entirety. Programs and participating artists follow. National Gallery of Art TWELFTH AMERICAN MUSIC FESTIVAL The A. W. Mellon Concerts Sunday, April 2It - United States Naval Academy Glee Club and Instrumentalists Donald C 0 Gilley., Director Randall Thompson #The Last Words of David John Jacob Niles Two Folk Songs Leonard Bernstein Pirate Song, from "Peter Pan" Paul Creston *Here is Thy Footstool William Schuman Holiday Song Donald C. Gilley ##Quintet for Organ and Strings Randall Thompson The Testament of Freedom, after writings of Thomas Jefferson Sunday, May 1 - National Gallery Orchestra Richard Bales, Conductor Soloist George Steiner, Violinist Grant Fletcher ^-Overture to "The Carrion Crow" Bernard Rogers *The Silver World Johan Franco ^Concerto Lirico, for Violin and Chamber Orchestra Willson Osborne #Saraband in Olden Style Robert Ward Symphony No.3 Sunday., May 8 - Concert sponsored by the Music Performance ——————— Trust Fund of the Recording Industry, through Local 161 of the American Federation of Musicians, National Gallery Orchestra Richard Bales, Conductor Soloist Theodore Schaefer, Organist George Frederick McKay **Suite for Strings, from the old "Missouri Harmony" Ned Rorem ^Symphony No.l - 19h9 Herbert E. -

The Perils of Baby Doe

The Perils of Baby Doe By Lewis J. Hardee, Jr. Columbia Library Columns Friends of the Columbia Libraries November 1973, Vol. 23, Issue #1 Those who have seen Douglas Moore's opera The Ballad of Baby Doe - and few devotees of American opera have not-will quickly recall the old turn-of-the-century prints that are projected onto a screen for entre-scene atmosphere. If these scenes, which have become traditional in Baby Doe productions across the country, bring to mind an old wild west melodrama, consider the reference appropriate: the history of this opera is a lively and sometimes perilous one. The story of Baby Doe first came to Douglas Moore's attention in 1935, during the ninth year of his long association with the Department of Music at Columbia University. On March 8 of that year he read in the New York Times an article, "Widow of Tabor freezes in shack; famed belle dies at 73 alone and penniless, guarding old Leadville bonanza mine." The article recounted the glamorous, tragic tale of Baby Doe Tabor, whose marriage to Horace Tabor, the Colorado silver baron, had delighted and scandalized the nation. A photograph appeared with the article showing "Elizabeth (Baby Doe Taylor[sic]) at the height of her famed beauty and social career." (Interestingly, this account parallels the scenario of the opera that was ultimately written. The headline, in fact, forms the basis for the opera's concluding scene.) The inherent poignancy of the story greatly appealed to Moore who immediately sensed its appropriateness as an operatic subject. -

Opera Program.Indd

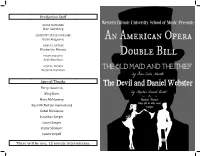

Production Staff STAGE MANAGER Matt Saltzberg ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Katie Ferguson DANCE CAPTAIN Kimberlyn Massey PROPS MASTER Scot Bouillon POSTER DESIGN Victoria Harmon Special Thanks Terry Chasteen Kitty Karn Mary McMurtery Ryan McNeil (in memoriam) Rebel Mickleson Jonathan Saeger Laura Saeger Penny Shumate James Stegall There will be one, 15 minute intermission. Director's Note MISS TODD Monica Tate On the surface, The Old Maid and the Thief and The Devil and Daniel GIAN CARLO MENOTTI Webster have a great deal in common. Both are one-act American operas. MISS PINKERTON Both are approximately one hour long. They premiered less than a month Parker Carls apart in the spring of 1939, both written by composers trained on the East The Old Maid coast: Menotti at Curtis, and Moore at Yale. LAETITIA And The Thief Claire Ryterski The Old Maid and the Thief was commissioned by NBC Radio. It premiered on April 22, 1939, and received its first staged production in 1941. The sto- A Grotesque Opera in Fourteen Scenes ry is light, and provides just a hint of the radio mysteries so popular in the BOB 1930s. It also pokes a bit of fun at prohibition (repealed only about 5 years Benjamin Rogers A small midwestern town, 1939 earlier); and no doubt, many of a certain age heard themselves in Miss Todd, as she ranted about being the chair of the “Prohibition POLICEMAN Committee” and having founded the “Anti-Booze.” Many also probably heard Zachary Palmer themselves as the domestic, Laetitia, or as the “wanderer” Bob… who was no doubt journeying because he could find no work, and had no place to live.