The Perils of Baby Doe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer

NWCR714 Douglas Moore / Marion Bauer Cotillion Suite (1952) ................................................ (14:06) 5. I Grand March .......................................... (2:08) 6. II Polka ..................................................... (1:29) 7. III Waltz ................................................... (3:35) 8. IV Gallop .................................................. (2:01) 9. V Cake Walk ............................................ (1:56) 10. VI Quickstep ............................................ (2:57) The Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra; Alfredo Antonini, conductor Symphony in A (1945) .............................................. (19:15) 11. I Andante con moto; Allegro giusto ....... (7:18) 12. II Andante quieto semplice .................... (5:39) 13. III Allegretto ............................................ (2:26) 14. IV Allegro con spirito .............................. (3:52) Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra; William Strickland, conductor Marion Bauer (1887-1955) Prelude & Fugue for flute & strings (1948) ................ (7:27) 15. Prelude ..................................................... (5:45) 16. Fugue ........................................................ (1:42) Suite for String Orchestra (1955) ................... (14:47) 17. I Prelude ................................................... (6:50) Douglas Moore (1893-1969) 18. II Interlude ................................................ (4:41) Farm Journal (1948) ................................................. (14:20) 19. III Finale: Fugue -

CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC for the Degree of MASTER of MUSIC By

ol 0002 -T-E CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA IN TVVENTIETH CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By U3arney C. Tiller, Jr., B. M., B. A. Denton, Texas January, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . II. THE HISTORY OF THE CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA . 5 III. ANALYSES OF SEVENTEEN CHACONNES AND PASSACAGLIAS FROM THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. 34 IV. CONCLUSIONS . 116 APPENDIX . 139 BIBLIOGRAPHY. * . * . * . .160 iii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Grouping of Variations According to Charac- teristics of Construction in the Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .. 40 TI. Thematic Treatment in the Chaconne from the Prelude, Toccata and Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .*0 . 41 III. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passacaglia and Fugue by Roland Diggle. 45 IV. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Moto Continuo and Passacglia by 'Herbert F. V. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia by Alan Gray . $4 VI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia b Robert . .*. -...... .... $8 Groves * - 8 VII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia by Ellis B. Kohs . 64 VIII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passaglia in A Minor by C. S. Lang . * . 73 IX. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passaca a andin D Minor by Gardner Read * . - - *. -#. *. 85 X. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacgland ugue by Healey Willan . 104 XI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacaglia and F by Searle Wright . -

Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor Madalyn W

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-12-2013 Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor Madalyn W. Mentor Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Mentor, Madalyn W., "Scholarly Program Notes on the Graduate Vocal Recital of Madalyn Mentor" (2013). Research Papers. Paper 393. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/393 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR by Madalyn Mentor B.A., Berea College, 2011 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music School of Music Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2013 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR By Madalyn Mentor A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Vocal Performance Approved by: Dr. Jeanine Wagner, Chair Dr. Susan Davenport Dr. Paul Transue Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 12, 2013 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF MADALYN MENTOR, for the Master of Music degree in VOCAL PERFORMANCE, presented on April 12, 2013, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR THE GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL OF MADALYN MENTOR MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

Music Festival Will Be Presented on Successive

NEWS RELEASE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Washington, D. C. Republic 7-U215, extension 282 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TWELFTH ANNUAL AMERICAN MUSIC FESTIVAL AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART Washington, April 8, 19"?£s David E0 Finley, Director of the National Gallery of art, announced today that the Gallery's Twelfth American Music Festival will be presented on successive Sunday evenings from April ?l|th through May 29th Six programs will be played, including orchestral, chamber, piano, and choral music. The series is under the general direction of Richard Bales, who will conduct the two orchestral concerts. These concerts will be given in the East Garden Court, beginning at Q; 00 P. Mo There is no admission charge, and tickets and reservations are not required. Station WGMS and the Good Music Network will broadcast these programs in their entirety. Programs and participating artists follow. National Gallery of Art TWELFTH AMERICAN MUSIC FESTIVAL The A. W. Mellon Concerts Sunday, April 2It - United States Naval Academy Glee Club and Instrumentalists Donald C 0 Gilley., Director Randall Thompson #The Last Words of David John Jacob Niles Two Folk Songs Leonard Bernstein Pirate Song, from "Peter Pan" Paul Creston *Here is Thy Footstool William Schuman Holiday Song Donald C. Gilley ##Quintet for Organ and Strings Randall Thompson The Testament of Freedom, after writings of Thomas Jefferson Sunday, May 1 - National Gallery Orchestra Richard Bales, Conductor Soloist George Steiner, Violinist Grant Fletcher ^-Overture to "The Carrion Crow" Bernard Rogers *The Silver World Johan Franco ^Concerto Lirico, for Violin and Chamber Orchestra Willson Osborne #Saraband in Olden Style Robert Ward Symphony No.3 Sunday., May 8 - Concert sponsored by the Music Performance ——————— Trust Fund of the Recording Industry, through Local 161 of the American Federation of Musicians, National Gallery Orchestra Richard Bales, Conductor Soloist Theodore Schaefer, Organist George Frederick McKay **Suite for Strings, from the old "Missouri Harmony" Ned Rorem ^Symphony No.l - 19h9 Herbert E. -

Opera Program.Indd

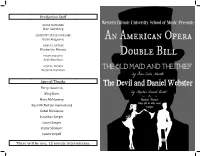

Production Staff STAGE MANAGER Matt Saltzberg ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Katie Ferguson DANCE CAPTAIN Kimberlyn Massey PROPS MASTER Scot Bouillon POSTER DESIGN Victoria Harmon Special Thanks Terry Chasteen Kitty Karn Mary McMurtery Ryan McNeil (in memoriam) Rebel Mickleson Jonathan Saeger Laura Saeger Penny Shumate James Stegall There will be one, 15 minute intermission. Director's Note MISS TODD Monica Tate On the surface, The Old Maid and the Thief and The Devil and Daniel GIAN CARLO MENOTTI Webster have a great deal in common. Both are one-act American operas. MISS PINKERTON Both are approximately one hour long. They premiered less than a month Parker Carls apart in the spring of 1939, both written by composers trained on the East The Old Maid coast: Menotti at Curtis, and Moore at Yale. LAETITIA And The Thief Claire Ryterski The Old Maid and the Thief was commissioned by NBC Radio. It premiered on April 22, 1939, and received its first staged production in 1941. The sto- A Grotesque Opera in Fourteen Scenes ry is light, and provides just a hint of the radio mysteries so popular in the BOB 1930s. It also pokes a bit of fun at prohibition (repealed only about 5 years Benjamin Rogers A small midwestern town, 1939 earlier); and no doubt, many of a certain age heard themselves in Miss Todd, as she ranted about being the chair of the “Prohibition POLICEMAN Committee” and having founded the “Anti-Booze.” Many also probably heard Zachary Palmer themselves as the domestic, Laetitia, or as the “wanderer” Bob… who was no doubt journeying because he could find no work, and had no place to live. -

MOORE, Douglas 2

Box MOORE, Douglas 2 ORGANIZATION OF THE PAPERS PAGE Cataloged correspondence: A-W, Box 1 3 Cataloged correspondence: Moore, Douglas Stuart to Myra D. Moore, Boxes 2-9 3 Arranged correspondence: Moore family correspondence. Box 10 3 Arranged correspondence (topically and chronologically): Boxes 11-19 3-5 Columbia University course material, Boxes 20 & 21 5 & 6 Printed scores and books inscribed to Moore, Boxes 22 & 23 6 Manuscript scores and sketches by Moore, Boxes 24-44 6 - 9 Film of "Gallantry" as performed on a CBS television program (2 reels), Box 45 9 Ms Coll/Moore, D. Douglas Moore Papers, 1907-1963 21 linear feet. (ca. 200 items in 45 boxes and 1 flatbox) Biography/History: Douglas Moore was composer who succeeded Daniel Gregory Mason as head of the music department at Columbia University in 1940. He was born in Cutchogue, New York on 10 August 1893 and died in Greenport Long Island on 25 July 1969. He was educated at Yale University and B.A., 1915 and Mus. Bac. 1917. Known mostly for his operas he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Giants in the Earth 1951. Summary: Professional and personal correspondence and original scores and sketches. In addition to the numerous original compositions, thre are letters and related materials dealing with these works. These include production notes, libretos and data concerning the production and performances of such works as: "The Ballad of Baby Doe," "The Devil and Daniel Webster," "Giants in the Earth," and "White Wings." There is material relating to the curriculum and administration of Columbia's Music Department, of which Moore was chairman from 1926. -

CONITZ-DOCUMENT-2019.Pdf

i Abstract (Re)Examining narratives: Personal style and the viola works of Quincy Porter (1897–1966) By Aaron Daniel Conitz The American composer Quincy Porter (1897–1966) is primarily remembered for his achievements and contributions as a member of the academy and, as a result, his music has largely been cast in the shadows. His compositional style is frequently described as “personal” or “highly individual,” particularly in reference to his works of chamber music, specifically those for string instruments. Porter was a fine violist who performed throughout his professional career in solo recitals and chamber ensembles; these experiences directly influenced his composition. Reexamining Porter’s narrative through the lens of his works for viola reveals a more nuanced perspective of the individual, one that more effectively conveys his personal style through the instrument he played. This body of repertoire forms a unique sector of his oeuvre: the works are valuable for the violist in their idiomatic qualities and compositional appeal, yet also display the composer’s voice at its finest. This document will present the works Porter originally wrote for viola (no transcriptions) as a valuable contribution to the repertory of 20th century American viola music. The works will be presented in chronological fashion and explore analytical aspects, stylistic concerns, historical context, and performance practice. The document begins with a biography to provide context for these works. ii Acknowledgements It is said that it takes a small village to raise a child. The essence and wisdom of this statement has certainly held true throughout the creation of this document; I would like to thank and recognize the small village of individuals that have helped me along this long, but rewarding journey. -

The American Composers Alliance Music Catalog and Archives: A

Essays e relationship between ACA and The American Composers Alliance music SCPA is a unique one, encompassing the catalog and archives: A collaborative effort normal functions of a music publisher as well as a music archive. For a number between ACA, BMI, and the University of of years SCPA has acted as custodian for ACA scores and parts. Maryland SCPA makes ACA scores available ac- cording to normal library policy, but it By Gina Genova also makes them available to ACA for In the first ACA Bulletin published in lection of scores and parts in collaboration digital scanning. 1938, the “Aims of the Alliance” were with the University of Maryland’s Special At ACA, we wish to preserve the ma- stated as: “To encourage the inclusion of Collections in Performing Arts (SCPA). terials entrusted to us as part of our his- American works in concerts.” In 2010, after an inventory of all scores tory for tomorrow’s generations. We e approach to fostering performan- was completed, we turned our atten- could not have moved forward in this ces of these American works over time has tion to processing the archival historical mission without the support of SCPA been to leverage ACA’s ability to provide files—the official records of ACA. is and the University of Maryland Libraries. access to its scores through publishing and ongoing project is now online at http:// When I first began working at ACA in distribution services. hdl.handle.net/1903.1/30672 the beginning of 2008, I knew about its Access to scores and performance mate- e official papers of ACA include all historic publishing catalog, but I didn’t rials is fundamental. -

The Implications of the American Symphonic Heritage in Contemporary Orchestral Modeling

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 11-11-2020 The Implications of the American Symphonic Heritage in Contemporary Orchestral Modeling Mathew Lee Ward Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ward, Mathew Lee, "The Implications of the American Symphonic Heritage in Contemporary Orchestral Modeling" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5407. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5407 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE AMERICAN SYMPHONIC HERITAGE IN CONTEMPORARY ORCHESTRAL MODELING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mathew Lee Ward U.D., Longy School of Music of Bard College, 2015 M.M., Longy School of Music of Bard College, 2017 December 2020 ii One hundred years ago our country was new and but partially settled. Our necessities compelled us to chiefly expend our means and time in felling forests, subduing prairies, building dwellings, factories, ships, docks, warehouses, roads, canals, machinery, etc. Most of our schools, churches, libraries and asylums have been established within a hundred years. Burdened by these great primal works of necessity which could not be delayed, we have yet done what this exhibition will show in the direction of rivaling older and more advanced nations in medicine and theology; in science, literature and the fine arts; while proud of what we have done, we regret that we have not done more. -

Can't Help but CRI TUESDAY, JANUARY 21, 2003 at 4 A.M

Can't Help but CRI TUESDAY, JANUARY 21, 2003 AT 4 A.M. I started collecting records when I was 12, in 1968 in Dallas. My dad would take me to work with him at Mobil Oil, and I'd run down the street to the downtown record store, whatever its name was. Records were six dollars, frequently on sale for four, and many was the month in the next 10 years that I would spend every cent I could get on them. I had no idea what I was doing. Raised on Mozart and Rachmaninoff, ambitious to know everything, I'd buy any record by a composer I'd never heard of, figuring most such names were 20th century. And after a while I realized that most of the composers I'd never heard of were on a label called CRI— Composers Recordings Incorporated. I got to where I'd buy anything on CRI. So when rumors started circulating that CRI was about to close down, and the confirmation came last week, it knocked the breath out of me—like a piece of my childhood taken away. The company had been founded in 1954 by composers Otto Luening and Douglas Moore and arts administrator Oliver Daniel. In the early days I found Cage's on that label, with Maro Ajemian playing—a crucial recording. I found Henry Brant's , most of the Dane Rudhyar recordings, lots of Ralph Shapey. Loads of historical stuff otherwise forgotten: the Quincy Porter "Elegiac" Quintet, the excellent Piano Concerto by the sadly neglected Ben Weber, all of the available Wallingford Riegger recordings, Robert Ward's opera .