'Nowhere Is Safe For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

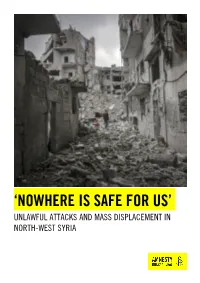

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects

JOURNAL OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 VOL. 43, NO. 1, 74–84 https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1410919 The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects: A View from the Ground Neil Brodiea and Isber Sabrineb aUniversity of Oxford, Oxford, UK; bUniversitat de Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The illegal excavation and trade of cultural objects from Syrian archaeological sites worsened Syria; looting; cultural markedly after the outbreak of civil disturbance and conflict in 2011. Since then, the damage to objects; coins; policy archaeological heritage has been well documented, and the issue of terrorist funding explored, but hardly any research has been conducted into the organization and operation of theft and trafficking of cultural objects inside Syria. As a first step in that direction, this paper presents texts of interviews with seven people resident in Syria who have first-hand knowledge of the trade, and uses information they provided to suggest a model of socioeconomic organization of the Syrian war economy regarding the trafficking of cultural objects. It highlights the importance of coins and other small objects for trade, and concludes by considering what lessons might be drawn from this model to improve presently established public policy. Introduction conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/). Nevertheless, most of what is known about illegal excavation and trade inside Like that of many countries in the Middle East and North Syria comes from some of the better media reporting, Africa (MENA) region, for the past few decades the archaeo- which has on occasion managed to access people with first- logical heritage of Syria has been robbed of cultural objects for hand knowledge or experience of the problem. -

Turkey's Approach to Proxy War in the Middle East and North Africa

https://securityandefence.pl/ Turkey’s approach to proxy war in the Middle East and North Africa Engin Yüksel [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1448-6059 Conflict Research Unit, Clingendael Institute, Clingendael 7, 2597 VH Den Haag, Netherlands Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University, Rapenburg 70, 2311 EZ Leiden, Netherlands Abstract The last decade has seen a growing trend towards the use of proxies in the Middle East and North Africa following the outbreak of the Arab Spring. In this context, the issue of Turkey’s approach to proxy war in these regions has received considerable atten- tion since 2016. Thereby, the purpose of this article is to investigate the essential characteristics of Turkish proxy war strategy in Syria and Libya. As such, this study intends to trace the development of Turkish proxy war strategy by making use of the con- ceptual frameworks proposed by Groh (2019), O’Brien (2012) and Art (1998). The most obvious finding to emerge from the analysis is that Turkey changed its indirect intervention strategy from donated assistance to proxy warfare in Syria and Libya when it saw a greater need to influence the result of the conflicts. In the case of Syria, this study has shown that the control- through-centralisation approach towards the Armed Syrian Opposition has enabled Turkey to carry out an effective proxy war strategy from 2016 onwards. In Libya, the results of this investigation have shown that theTurkish Army has pursued a proxy war strategy since Ankara and the Government of National Accord (GNA) signed an agreement on security and military coop- eration in December 2019. -

The Political Direction of Which Ariel Sharon's Disengagement Plan Forms a Part Is the Most Significant Development in Israe

FRAGMENTED SYRIA: THE BALANCE OF FORCES AS OF LATE 2013 By Jonathan Spyer* Syria today is divided de facto into three identifiable entities. These three entities are: first, the Asad regime itself, which has survived all attempts to divide it from within. The second area is the zone controlled by the rebels. In this area there is no central authority. Rather, the territory is divided up into areas controlled by a variety of militias. The third area consists of majority-Kurdish northeast Syria. This area is under the control of the PYD (Democratic Union Party), the Syrian franchise of the PKK. This article will look into how this situation emerged, and examine its implications for the future of Syria. As the Syrian civil war moves toward its The emergence of a de facto divided Syria fourth anniversary, there are no signs of is the result first and foremost of the Asad imminent victory or defeat for either of the regime’s response to its strategic predicament sides. The military situation has reached a in the course of 2012. By the end of 2011, the stalemate. The result is that Syria today is uprising against the regime had transformed divided de facto into three identifiable entities, from a largely civilian movement into an each of which is capable of defending its armed insurgency, largely because of the existence against threats from either of the regime’s very brutal and ruthless response to others. civilian demonstrations against it. This These three entities are: first, the Asad response did not produce the decline of regime itself, which has survived all attempts opposition, but rather the formation of armed to divide it from within. -

Moscow Summit: Will the Ceasefire Hold in Idlib?

Situation Assessement | 10 March 2020 Moscow Summit: Will the Ceasefire Hold in Idlib? Unit for Political Studies Moscow Summit? Series: Situation Assessement 10 March 2020 Unit for Political Studies The Unit for Political Studies is the Center’s department dedicated to the study of the region’s most pressing current affairs. An integral and vital part of the ACRPS’ activities, it offers academically rigorous analysis on issues that are relevant and useful to the public, academics and policy-makers of the Arab region and beyond. The Unit for Political Studie draws on the collaborative efforts of a number of scholars based within and outside the ACRPS. It produces three of the Center’s publication series: Assessment Report, Policy Analysis, and Case Analysis reports. Copyright © 2020 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non- Arab researchers. The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies Al-Tarfa Street, Wadi Al Banat Al-Dayaen, Qatar PO Box 10277, Doha +974 4035 4111 www.dohainstitute.org Moscow Summit? Series: Situation Assessement Table of Contents 10 March 2020 Terms of the Agreement . -

WHEAT VALUE CHAIN ASSESSMENT North West - Syria June 2020

WHEAT VALUE CHAIN ASSESSMENT North West - Syria June 2020 Shafak & MH Europe Organizations Contents 1 Humanitarian Needs Overview ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 Methodology and Approach................................................................................................................................... 3 3 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 4 Locations .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 5 Assessment Findings ................................................................................................................................................ 7 5.1 Affected population demographics: ............................................................................................. 7 5.2 Affected people main occupation: ................................................................................................ 7 5.3 Agriculture land-farmers: ................................................................................................................... 9 5.4 farmers Challenges: ............................................................................................................................. 10 5.5 Main Cultivated Crops: ...................................................................................................................... -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

Covid-19: Tool of Conflict Or Opportunity for Local Peace in Northwest Syria

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). Research Report July 2021 C ovid-19: Tool of Conflict or Opportunity for Local Peace in Northwest Syria? © Baraa Obied Juline Beaujouan Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP) at the University of Edinburgh Acknowledgements This research is an output from the Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP), a partner in the Covid Collective. Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges. Opinions stated in this brief are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Covid Collective, its partners, or FCDO. Any use of this work should acknowledge the author and the Political Settlements Research Programme. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the PSRP website. Thanks are due to Christine Bell for peer review and editorial advice, and to Eyas Ghreiz and Abdulah El hafi for collaborating on the study and offering feedback on various versions of the draft. Thanks to Harriet Cornell for editing and production work. Thanks to the Blue Team and Civilization Team for illustrating the report with original artwork. The author hereby thanks all the people who took the time to participate in this study and all the collaborators who contributed to this project. -

Syria Regional Program Ii Final Report

SYRIA REGIONAL PROGRAM II FINAL REPORT November 2, 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. SYRIA REGIONAL PROGRAM II FINAL REPORT Contract No. AID-OAA-I-14-00006, Task Order No. AID-OAA-TO-15-00036 Cover photo: Raqqa’s Al Naeem Square after rehabilitation by an SRP II grantee. (Credit: SRP II grantee) DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................................ iv Executive Summary and Program Overview ..................................................... 1 Program Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. Country Context ................................................................................................. 3 A. The Regime’s Reconquest of Western Syria with Russian and Iranian Support ........ 3 B. The Territorial Defeat of ISIS in Eastern Syria ................................................................... 5 C. Prospects for the Future ......................................................................................................... 7 II. Program Operations ......................................................................................... 8 A. Operational -

Syria Market Monitoring Exercise Cash-Based Responses Snapshot: 16-23 October 2017 Technical Working Group

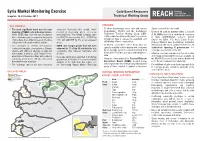

Syria Market Monitoring Exercise Cash-Based Responses Snapshot: 16-23 October 2017 Technical Working Group KEY FINDINGS OVERVIEW • The most significant trend was the near currencies decreased this month, which • To inform humanitarian actors’ cash and voucher Syrian household for one month. doubling of SMEB costs in besieged areas. resulted in decreasing prices of several programming, REACH and the Cash-Based • Between 16 and 23 October 2017, a network While SMEB data collected was incomplete assessed items. The median exchange rates Responses Technical Working Group (CBR– of 12 NGOs involved in cash-based responses due to shortages and consequently the paucity for USD/SYP decreased by 10%, TRY/SYP by TWG) conduct monthly monitoring of key markets in Syria (CARE/Shafak, Concern, Danish of price data, the sudden increase in the price 10%, and JOD/SYP by 5% across assessed throughout Syria to assess the availability and Church Aid, GOAL, IRC, Mercy Corps, People of key items in the past month is evident. areas. affordability of basic commodities. in Need, REACH, Save the Children, Solidarités • The shortages of chicken and potatoes • SMEB cost changes greater than 10% were • Monitored commodities reflect those that are International and Violet) contributed data from 72 continued in multiple communities in Eastern observed in 11 of the 50 subdistricts with typically available, sold in markets and consumed subdistricts spanning 11 governorates. For Ghouta, with additional shortage of eggs and comparable data between September and by an average Syrian household including food coverage, see the map on the left. milk in Arbin. In addition, LPG continues to be October. -

S/PV.8449 the Situation in the Middle East, Including the Palestinian Question 22/01/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8449 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8449th meeting Tuesday, 22 January 2019, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Singer Weisinger/Mr. Trullols ................... (Dominican Republic) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Ma Zhaoxu Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Ipo Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Ndong Mba France ........................................ Mr. Delattre Germany ...................................... Mr. Heusgen Indonesia. Mrs. Marsudi Kuwait ........................................ Mr. Alotaibi Peru .......................................... Mr. Meza-Cuadra Poland ........................................ Ms. Wronecka Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Nebenzia South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Ms. Pierce United States of America .......................... Mr. Cohen Agenda The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question . This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 19-01678 (E) *1901678* S/PV.8449 The situation in the Middle East, including the Palestinian question 22/01/2019 The meeting was called to order at 10.05 a.m. with the provisional rules of procedure and previous practice in this regard. Expression of sympathy in connection with and There being no objection, it is so decided. -

Policy Notes July 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY JULY 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 108 Deals, Drones, and National Will The New Era in Turkish Power Projection Rich Outzen he Turkish Armed Forces (TAF) attracted much attention in 2020 for its devastating employment of unmanned aerial vehicles during combat in TSyria, Libya, and the Caucasus. UAVs (drones) were just one dimension of Turkish regional interventions, but they were particularly potent symbols in an age of ubiquitous cameras and Internet connections.1 A number of analysts have assessed the tactical and operational impact of Turkish drones.2 Yet the Turkish drone program is just part of a revamped national approach to power Photo: Yasin Bulbul/ projection in neighboring regions—an approach with economic, diplomatic, Presidential Palace/Handout strategic, and reputational effects, as well as implications on the battlefield. via REUTERS An expanded network of Turkish military agreements and overseas basing, the maturation of partner and proxy relationships, the expansion of the defense industry beyond UAVs, military doctrine to integrate new sensors RICH OUTZEN DEALS, DRONES, AND NATIONAL WILL and weapons, and—perhaps most critically—the development of risk-tolerant political will in foreign Abbreviations affairs have enabled Turkey to become a formidable hard-power player in the Middle East, North Africa, GNA Government of National Accord (Libya) the Caucasus, and the Black and Mediterranean Seas. Scholarly analysis is therefore needed that LNA Libyan National Army both contextualizes new capabilities for Western audiences and assesses the role and impact of these MIT Milli Istihbarat Teskilati (Turkey’s developments for the coming years. Signaling larger National Intelligence Organization) change within the Turkish military, drones represent a technical leap wrapped in a “revolution in military PKK Kurdistan Workers Party (Turkey) affairs” embedded in a regional realignment.