Transoceanic Studies Ileana Rodríguez, Series Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

209113-Sample.Pdf

Sample file Credits Designer: Tyler ‘Walrock’ Reed Special Thanks: The Discord of Many Things, /r/unearthedar- DM’s Guild: walrockhomebrew.com cana, /r/dndnext, /u/skybug12, /u/Smyris, and all our backers Patreon: patreon.com/walrockhomebrew on Patreon! Twitter: @WalrockHomebrew Blog: walrock-homebrew.blogspot.com Legal: DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, Ravenloft, Eberron, the dragon ampersand, Illustrators via Adobe Stock License: Bernardojbp, Gekata1989, Ravnica and all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and Ekaterina Glazkova, Iulia Kovalova, Tithi Luadthong, Viktoria their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in Manuilova, Marina, Mollicart, Anna Nenasheva, info@ the USA and other countries. nextmars.com, Saphatthachat, Kate Vigdis, Zhenliu Illustrators via DM’s Guild Licence: David Michael Beck, Ed This work contains material that is copyright Wizards of the Coast Cox, Stephen Crowe, Michael Dutton, Wayne England, Tomas and/or other authors. Such material is used with permission under Giorello, Rebecca Guay, Fred Hopper, Doug Kovacs, David the Community Content Agreement for Dungeon Masters Guild. Martin, Mats Minnigan, Jim Nelson, Steve Prescott, Anne Stokes, Joel Thomas, Eva Widermann Some artwork © 2015 Dean Spencer, used with permission. All Illustrators via Individual Licence: Daniele Ariuolo, Gary Dupuis, rights reserved. Some artwork copyright Kii W - https://twitter. Forrest Imel, Vagelio Kaliva, Matt Morrow, David Revoy, com/kiichan - used with permission. Some artwork © 2015 Vage- Dean Spencer lio Kaliva, used with permission. All rights reserved. Illustrators via Public Domain: Boris Kustodiev All other original material in this work is copyright 2020 by Walrock Homebrew and published under the Community Content Agree- ment for Dungeon Masters Guild. -

Keith Carlock

APRIZEPACKAGEFROM 2%!3/.34/,/6%"),,"25&/2$s.%/.42%%3 7). 3ABIANWORTHOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 'ET'OOD 4(%$25--%23/& !,)#)!+%93 $!.'%2-/53% #/(%%$ 0,!.4+2!533 /.345$)/3/5.$3 34!249/52/7. 4%!#().'02!#4)#% 3TEELY$AN7AYNE+RANTZS ,&*5)$"3-0$,7(9(%34(%-!.4/7!4#( s,/52%%$34/.9h4(5.$%2v3-)4( s*!+),)%"%:%)4/&#!. s$/5",%"!3335"34)454% 2%6)%7%$ -/$%2.$25--%2#/- '2%43#(052%7//$"%%#(3/5,4/.%/,$3#(//,3*/9&5,./)3%%,)4%3.!2%3%6!.34/-0/7%2#%.4%23 Volume 35, Number 3 • Cover photo by Rick Malkin CONTENTS 48 31 GET GOOD: STUDIO SOUNDS Four of today’s most skilled recording drummers, whose tones Rick Malkin have graced the work of Gnarls Barkley, Alicia Keys, Robert Plant & Alison Krauss, and Coheed And Cambria, among many others, share their thoughts on getting what you’re after. 40 TONY “THUNDER” SMITH Lou Reed’s sensitive powerhouse traveled a long and twisting musical path to his current destination. He might not have realized it at the time, but the lessons and skills he learned along the way prepared him per- fectly for Reed’s relentlessly exploratory rock ’n’ roll. 48 KEITH CARLOCK The drummer behind platinum-selling records and SRO tours reveals his secrets on his first-ever DVD, The Big Picture: Phrasing, Improvisation, Style & Technique. Modern Drummer gets the inside scoop. 31 40 12 UPDATE 7 Walkers’ BILL KREUTZMANN EJ DeCoske STEWART COPELAND’s World Percussion Concerto Neon Trees’ ELAINE BRADLEY 16 GIMME 10! Hot Hot Heat’s PAUL HAWLEY 82 PORTRAITS The Black Keys’ PATRICK CARNEY 84 9 REASONS TO LOVE Paul La Raia BILL BRUFORD 82 84 96 -

Monster Manual

CREDITS MONSTER MANUAL DESIGN MONSTER MANUAL REVISION Skip Williams Rich Baker, Skip Williams MONSTER MANUAL D&D REVISION TEAM D&D DESIGN TEAM Rich Baker, Andy Collins, David Noonan, Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, Rich Redman, Skip Williams Skip Williams ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT ADDITIONAL DESIGN David Eckelberry, Jennifer Clarke Peter Adkison, Richard Baker, Jason Carl, Wilkes, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, William W. Connors, Sean K Reynolds Bill Slavicsek EDITORS PROOFREADER Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Jon Pickens Penny Williams EDITORIAL ASSITANCE Julia Martin, Jeff Quick, Rob Heinsoo, MANAGING EDITOR David Noonan, Penny Williams Kim Mohan MANAGING EDITOR D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kim Mohan Ed Stark CORE D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D Ed Stark Bill Slavicsek DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D ART DIRECTOR Bill Slavicsek Dawn Murin VISUAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR COVER ART Jon Schindehette Henry Higginbotham ART DIRECTOR INTERIOR ARTISTS Dawn Murin Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren D&D CONCEPTUAL ARTISTS Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Todd Lockwood, Sam Wood Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Scott Fischer, Rebecca Guay-Mitchell, Jeremy Jarvis, D&D LOGO DESIGN Paul Jaquays, Michael Kaluta, Dana Matt Adelsperger, Sherry Floyd Knutson, Todd Lockwood, David COVER ART Martin, Raven Mimura, Matthew Henry Higginbotham Mitchell, Monte Moore, Adam Rex, Wayne Reynolds, Richard Sardinha, INTERIOR ARTISTS Brian Snoddy, Mark Tedin, Anthony Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren Waters, Sam Wood Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Larry Elmore, GRAPHIC -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE INCORPORATING MULTIPLE HISTORIES: THE POSSIBILITY OF NARRATIVE RUPTURE OF THE ARCHIVE IN V. AND BELOVED A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By LEANN MARIE STEVENS-LARRE Norman, Oklahoma 2010 INCORPORATING MULTIPLE HISTORIES: THE POSSIBILITY OF NARRATIVE RUPTURE OF THE ARCHIVE IN V. AND BELOVED A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY _____________________________________________ Dr. Timothy S. Murphy, Chair _____________________________________________ Dr. W. Henry McDonald _____________________________________________ Dr. Francesca Sawaya _____________________________________________ Dr. Rita Keresztesi _____________________________________________ Dr. Julia Ehrhardt © Copyright by LEANN MARIE STEVENS-LARRE 2010 All Rights Reserved. This work is dedicated to the woman who taught me by her example that it was possible. Thank you, Dr. Stevens, aka, Mom. Acknowledgements I am and will always be genuinely grateful for the direction of my dissertation work by Tim Murphy. He was thorough, rigorous, forthright, always responding to my drafts and questions with lightening speed. Whatever is good here is based on his guidance, and whatever is not is mine alone. I know that I would not have been able to finish this work without him. I also appreciate the patience and assistance I received from my committee members, Henry McDonald, Francesca Sawaya, Rita Keresztesi, and Julia Ehrhardt. I have benefitted greatly from their experience, knowledge and encouragement. Henry deserves special recognition and heartfelt thanks for sticking with me through two degrees. I would also like to thank Dr. Yianna Liatsos for introducing me to ―the archive.‖ I most sincerely thank (and apologize to) Nancy Brooks for the tedious hours she spent copy-editing my draft. -

Dragonlance Uniche

1 LP. i Autori: Margaret Weis, Don Perrin, Jarnie Charnbers, Christopher Coyle Sviluppatori Richard Baker, James Wyatt Revisori Michele Carter, Cai Moore, Charles Ryan, Ray Vallese, Va1 Vallese Organizzatore revisori Kim M~hanh. Oqpnkmbre grafìci: Ed Stark Direttore artistico: Dawn Murin h. Illustrazione di coperhx Matt Stawicki Illustratori tavole interne: Dennis Cramer, Jeff Easley, Matthew Faullmer, Emily Fiegenschuh, Lars Grant-West, Rebecca Guay, Heather Hudson, Doug Kovacs, Ginger Kubic, John & Laura Lakey, David Martin, Matthew Mitchell, Vinod Rarns, Darre11 Riche, Richard Sardinha, Brian Snoddy, Ron Spencer Cartografì: Dennis Kauth, Rob Lazzaretti h. Impaghatore: Erin Dorries Grafici: Yasuyo Dunnett, Dawn Murin Direttore di R&D per i giochi di ruolo: Bill Slavicsek h. Vice presidente editoriale: Mary Gchoff Responsabile di categoria per i giochi di ruolo: Anthony Vaiterra Responsabile del progetto: Martin Durham h. Direttore di produzione: Chas DeLong Gli autori ringraziano per il loro contributo Cam Banks, Neil Burton, Weldon Chen, Richard Conm Patrick Coppo&-Terry Doetzel, Sean Everette, Luis Fernando De Pippo, Matt Haag, Digger Hayes, Eric Jwo, André La Roche, Sean Macdonaid, Tobin Meiroy, Frank Reinart, Sean K Reynolds, Trampas T. Whiteman. Basato sulle regole originali di DUNGEONS& DRAGONS~ create da Gary Gygax e Dave Arneson e sulle nuove regole DUNGEONS& DRAGONS create da Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Wdiam, Richard Baker e Peter Adkison. Questo prodotto WIZARDSOF THE COM@non contiene Open Garne Content. Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere riprodotta in alcuna forma senza permesso scritto. Per ulteriori informazioni sulla Open Gaming License e la d20" System License, consultate www.wizards.com/d20. 1 Direttore Responsabile: Emanuele Rastelii Supervisione e revisione: Massimo Bianchini Traduzione: Damiano Alfieri, Michele Bonelii di Salci, Fioremo delie Rupi Impaginazione: Giorgia Caiandroni EUROPEAN HEADQUARTERS Wmds of the Coast, B$gium T HoaFveld 6d TWENTY FIVE EDITION s.rJ. -

COMPLETE WARRIOR™ a Player’S Guide to Combat for All Classes ANDY COLLINS, DAVID NOONAN, ED STARK

COMPLETE WARRIOR™ A Player’s Guide to Combat for All Classes ANDY COLLINS, DAVID NOONAN, ED STARK ADDITIONAL DESIGN ART DIRECTOR JESSE DECKER DAWN MURIN DEVELOPMENT TEAM COVER ARTIST MICHAEL DONAIS (LEAD), ANDREW J. FINCH, WAYNE REYNOLDS RICHARD BAKER, DAVID ECKELBERRY INTERIOR ARTISTS EDITORS BRENT CHUMLEY, ED COX, WAYNE ENGLAND, DALE DONOVAN, KIM MOHAN REBECCA GUAY-MITCHELL, JEREMY JARVIS, MANAGING EDITOR DOUG KOVACS, GINGER KUBIC, JOHN AND KIM MOHAN LAURA LAKEY, DAVID MARTIN, DENNIS CRABAPPLE MCCLAIN, DESIGN MANAGER MATT MITCHELL, STEVE PRESCOTT, ED STARK WAYNE REYNOLDS, DAVID ROACH, MARK SMYLIE,BRIAN SNODDY, RON SPENCER, DEVELOPMENT MANAGER JOEL THOMAS ANDREW J. FINCH GRAPHIC DESIGNER DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D DAWN MURIN BILL SLAVICSEK VICE PRESIDENT OF PUBLISHING GRAPHIC PRODUCTION SPECIALIST MARY KIRCHOFF ANGELIKA LOKOTZ PROJECT MANAGER IMAGE TECHNICIAN MARTIN DURHAM JASON WILEY PRODUCTION MANAGER ORIGINAL INTERIOR DESIGN CHAS DELONG SEAN GLENN Sources: Sword and Fist by Jason Carl; Tome and Blood by Bruce R. Cordell and Skip Williams; Defenders of the Faith by Rich Redman and James Wyatt; Masters of the Wild by David Eckelberry and Mike Selinker; Song and Silence by David Noonan and John Rateliff; Oriental Adventures by James Wyatt; Epic Level Handbook by Andy Collins, Bruce R. Cordell, and Thomas M. Reid; various Dragon magazine issues and contributors including Andy Collins, Monte Cook, and Kolja Liquette. Based on the original DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® rules created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, and the new DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game designed by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkison. This WIZARDS OF THE COAST® game product contains no Open Game Content. -

TV Theme M a S H Tee Set Ma Belle Amie Mac Davis Mac Davis

TV Theme M A S H Tee Set Ma Belle Amie Mac Davis Mac Davis - Baby Don't Get Hooked On Me Los Del Rio Macarena Donna summer Macarthur Park Brother Cane Machete [Karaoke] Village People Macho Man Bobby Darin Mack The Knife Hooverphonic Mad About You Matchbox 20 Mad Season Gary Jules Mad World Stereophonics Madame helga Doug Stone Made For Lovin' You Elton John Made In England Elton John Madman Across The Water Muse Madness Jimmy Buffett Magaritaville Rod Stewart Maggie Mae Bob Dylan Maggies Farm B.o.B Magic Cars Magic Selena Gomez Magic Who magic Bus Steppenwolf Magic Carpet Ride Heart Magic Man Celine Dion Magic of Christmas Day Oasis MAGIC PIE TRIUMPH Magic Power Lil' Kim feat. 50 Cent Magic Stick Kiss Magic Touch Walter Egan Magnet and Steel Bob Segar Mainstreet Pirates of Penzance Major Generals Song Incubus Make A Move Kitty Wells Make Believe ('til We Can Make It Come True) Taking Back Sunday Make Damn Sure Busta Rhymes Make It Clap Mariah Carey Make It Happen Jason Mraz Make it Mine Ed sheeran Make It Rain Bread Make It With You Korn Make me Bad A Foot In Cold Water Make Me Do Anything You Want Kellie Pickler Make Me Fall In Love Again Elvis Make Me Know It Chicago make Me Smile Pretty Reckless Make Me Wanna Die Sandy B Make The World Go Around Christina Aquilera Make The World Move Doug Stone Make Up In Love Theroy of Deadman Make up your mind Adele Make You Feel MyLove Alabama Maker Said Take Her, The Maroon 5 Makes Me Wonder Sum 41 Makes No Difference Kitty Wells Makin' Believe Doug and the Slugs Makin It Work Kiss Makin Love Dr -

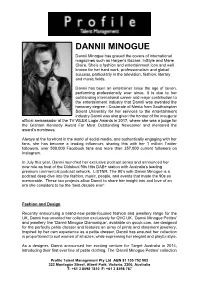

Dannii Minogue

DANNII MINOGUE Dannii Minogue has graced the covers of international magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, InStyle and Marie Claire. She’s a fashion and entertainment icon and well known for her hard work, professionalism and global success, particularly in the television, fashion, literary and music fields. Dannii has been an entertainer since the age of seven, performing professionally ever since. It is due to her outstanding international career and major contribution to the entertainment industry that Dannii was awarded the honorary degree - Doctorate of Media from Southampton Solent University for her services to the entertainment industry Dannii was also given the honour of the inaugural official ambassador at the TV WEEK Logie Awards in 2017, where she was a judge for the Graham Kennedy Award For Most Outstanding Newcomer and mentored the award’s nominees. Always at the forefront in the world of social media, and authentically engaging with her fans, she has become a leading influencer, sharing this with her 1 million Twitter followers, over 500,000 Facebook fans and more than 357,000 current followers on Instagram. In July this year, Dannii launched her exclusive podcast series and announced her new role as host of the Oldskool 90s Hits DAB+ station with Australia’s leading premium commercial podcast network, LiSTNR. The 90’s with Dannii Minogue is a podcast deep dive into the fashion, music, people, and events that made the 90s so memorable. These two projects allow Dannii to share her insight into and love of an era she considers to be the ‘best decade ever’. -

2 Column Indented

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

The Mother's Mark: Matrilineal Inscription, Corporeality

THE MOTHER’S MARK: MATRILINEAL INSCRIPTION, CORPOREALITY, AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN MOTHER-DAUGHTER RELATIONSHIPS IN BLACK WOMEN’S LITERATURE By Destiny O. Birdsong Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2012 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Ifeoma C. K. Nwankwo Professor Hortense J. Spillers Professor Lucius T. Outlaw, Jr. Professor Kate Daniels Copyright © 2012 by Destiny O. Birdsong All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was only possible through the funding of Vanderbilt University; particularly the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Science, and the English Department. Over the past six years, a PhD fellowship, a graduate assistantship, a dissertation-year fellowship, an Arts and Sciences Dean’s Select Award, work study opportunities, travel grants, and other forms of funding have all been indispensable in the completion of this project. Additionally, several semester-long fellowships at the Vanderbilt University Writing Studio not only helped me discover my great love for working with student writers, but also gave me the opportunity to improve my own writing skills. I owe a special thanks to the director, Jennifer Holt, whose work with me during the revision stage of this dissertation has truly transformed it. Jen, I cannot emphasize how valuable your feedback has been—both to this process as well as to my development as a writer. Thank you. I was also fortunate to have a wonderful support system in the English Department. Professors Jay Clayton and Mark Schoenfield, who both served as departmental chairs during my time here, have helped in a variety of capacities. -

Draconomicon, the Book of Dragons

DRACONOMICON™ Andy Collins, Skip Williams, James Wyatt DEVELOPER ART DIRECTOR Andy Collins Dawn Murin DESIGN ASSISTANCE COVER ART Ed Stark, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel Todd Lockwood EDITORS INTERIOR ARTISTS Michele Carter, Dale Donovan, Wayne England, Emily Fiegenschuh, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Charles Ryan Lars Grant-West, Rebecca Guay-Mitchell, David Hudnut, Jeremy Jarvis, Ginger Kubic, MANAGING EDITOR John & Laura Lakey, Todd Lockwood, Kim Mohan David Martin, Dennis Crabapple- McClain, Matt Mitchell, Mark Nelson, D&D DESIGN MANAGER Steve Prescott, Vinod Rams, Richard Ed Stark Sardinha, Ron Spencer, Stephen Tappin, Joel Thomas, Ben Thompson, Sam Wood DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D Bill Slavicsek GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Dawn Murin, Mari Kolkowski VICE PRESIDENT OF PUBLISHING Mary Kirchoff CARTOGRAPHER Todd Gamble PROJECT MANAGER Martin Durham GRAPHIC PRODUCTION SPECIALISTS Erin Dorries, Angelika Lokotz PRODUCTION MANAGER ORIGINAL INTERIOR DESIGN Chas DeLong Sean Glenn This d20™ System game utilizes mechanics developed for the new Dungeons & Dragons® game by Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Baker, and Peter Adkison. This WIZARDS OF THE COAST® product contains no Open Game Content. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form with- out written permission. To learn more about the Open Gaming License and the d20 System License, please visit www.wizards.com/d20. Playtesters: Greg Collins, Jesse Decker, Viet Nguyen, Marc Russell, Dennis Worrell Valuable advice provided by Todd Lockwood and Sam Wood (Dragon Anatomy and Motion), Monica Shellman