Pastoralism in India: a Scoping Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steppe Nomads in the Eurasian Trade1

Volumen 51, N° 1, 2019. Páginas 85-93 Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena STEPPE NOMADS IN THE EURASIAN TRADE1 NÓMADAS DE LA ESTEPA EN EL COMERCIO EURASIÁTICO Anatoly M. Khazanov2 The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated. Key words: Steppe nomads, Eurasian trade, the Silk Road, caravans. Los nómadas de las estepas, semidesiertos y desiertos euroasiáticos desempeñaron un papel importante y múltiple en el tránsito regional e interregional y en el comercio de larga distancia en Eurasia. En tiempos antiguos y medievales, su papel superó con creces su número de habitantes y su potencial económico. El carácter especializado y no autárquico de su economía provocó que los nómadas siempre experimentaran la necesidad de contar con productos externos agrícolas y artesanales. Además, exitosos Estados y comunidades nómadas crearon una demanda por el comercio internacional de bienes exóticos de alto valor, e incluso proporcionaron suministros, especialmente seda, para este comercio. -

Adaptation of the List of Backward Classes Castes/ Comm

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA ABSTRACT Backward Classes Welfare Department – Adaptation of the list of Backward Classes Castes/ Communities and providing percentage of reservation in the State of Telangana – Certain amendments – Orders – Issued. Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department G.O.MS.No. 16. Dated:11.03.2015 Read the following:- 1. G.O.Ms.No.3, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.14.08.2014 2. G.O.Ms.No.4, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.30.08.2014 3. G.O.Ms.No.5, Backward Classes Welfare (OP) Department, dated.02.09.2014 4. From the Member Secretary, Commission for Backward Classes, letter No.384/C/2014, dated.25.9.2014. 5. From the Director, B.C. Welfare, Telangana, letter No.E/1066/2014, dated.17.10.2014 6. G.O.Ms.No.2, Scheduled Caste Development (POA.A2) Department, Dt.22.01.2015 *** ORDER: In the G.O. first read above, orders were issued adapting the relevant Government Orders issued in the undivided State of Andhra Pradesh along with the list of (112) castes/communities group wise as Backward Classes with percentage of reservation, as specified therein for the State of Telangana. 2. In the G.O. second and third read above, orders were issued for amendment of certain entries at Sl.No.92 and Sl.No.5 respectively in the Annexure to the G.O. first read above. 3. In the letters fourth and fifth read above, proposals were received by the Government for certain amendments in respect of the Groups A, B, C, D and E, etc., of the Backward Classes Castes/Communities as adapted in the State of Telangana. -

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93)

Saurashtra University Re – Accredited Grade ‘B’ by NAAC (CGPA 2.93) Odedra, Nathabhai K., 2009, “Ethnobotany of Maher Tribe In Porbandar District, Gujarat, India”, thesis PhD, Saurashtra University http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu/id/eprint/604 Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Saurashtra University Theses Service http://etheses.saurashtrauniversity.edu [email protected] © The Author ETHNOBOTANY OF MAHER TRIBE IN PORBANDAR DISTRICT, GUJARAT, INDIA A thesis submitted to the SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY In partial fulfillment for the requirement For the degree of DDDoDoooccccttttoooorrrr ooofofff PPPhPhhhiiiilllloooossssoooopppphhhhyyyy In BBBoBooottttaaaannnnyyyy In faculty of science By NATHABHAI K. ODEDRA Under Supervision of Dr. B. A. JADEJA Lecturer Department of Botany M D Science College, Porbandar - 360575 January + 2009 ETHNOBOTANY OF MAHER TRIBE IN PORBANDAR DISTRICT, GUJARAT, INDIA A thesis submitted to the SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY In partial fulfillment for the requirement For the degree of DDooooccccttttoooorrrr ooofofff PPPhPhhhiiiilllloooossssoooopppphhhhyyyy In BBoooottttaaaannnnyyyy In faculty of science By NATHABHAI K. ODEDRA Under Supervision of Dr. B. A. JADEJA Lecturer Department of Botany M D Science College, Porbandar - 360575 January + 2009 College Code. -

A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes Working As Unorganised Labourers

Jenu Kuruba Tribes / 79 A Study on Life Style of Jenu Kuruba Tribes working as Unorganised Labourers * Pradeep M D ** Kalicharan M L Abstract Tribals usually are primitive people, living socially as homogeneous unit with their own culture different subsistence pattern, custom, superstitious beliefs, distinct life style living in isolation from outside influence. Forests are closely associated with the tribal economy and culture. Foreign invasion affected tribal life by assimilating through invading their culture. The independent India saw the legal takeover of prime tribal lands in the name of development dispelling millions of tribes. The Government of India adopted a policy to integrate tribes with modernization by encouraging partnership between the tribes and non tribes. The policy of integration or progressive acculturation has laid the foundation for the march of the tribes towards Equality, Upward Mobility, Economic viability and National mainstreaming. The tribes who are very backward are grouped into ‘Primitive Tribes’ having a low level of literacy, declining in population, poor technological access and extreme economic backwardness. Jenu Kuruba Tribes are one of the vulnerable Tribal Groups living in the state of Karnataka. This paper examines the socio-economic life of Jenu Kuruba Tribes covering personal profile, economic condition, literacy, housing pattern and the use of welfare schemes. This research will suggest ways for new interventions to solve the problems through the collective intervention of government officials, local administration, social workers, and the general public. Key Words: Tribes, Culture, Primitive People, Adjustment, Welfare. Introduction The word 'Tribe' is derived from the Latin word 'Tribus' meaning one among the three people, 'Ramayana' denotes 'Jana' the people with different physical appearance, having superstitious beliefs. -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Án Zimonyi, Medieval Nomads in Eastern Europe

As promised, after the appearance of Crusaders, in Slavic or Balkan languages, or Russian authors Missionaries and Eurasian Nomads in the 13th who confine themselves to bibliography in their 14th Centuries: A Century of Interaction, Hautala own mother tongue,” Hautala’s linguistic capabili did indeed publish an anthology of annotated ties enabled him to become conversant with the Russian translations of the Latin texts.10 In his in entire field of Mongol studies (14), for which all troduction, Spinei observes that “unlike WestEu specialists in the Mongols, and indeed all me ropean authors who often ignore works published dievalists, should be grateful. 10 Ot “Davida, tsaria Indii” do “nenavistnogo plebsa satany”: Charles J. Halperin antologiia rannikh latinskikh svedenii o tataromongolakh (Kazan’: Mardzhani institut AN RT, 2018). ——— István Zimonyi. Medieval Nomads in Eastern Part I, “Volga Bulgars,” the subject of Zimonyi’s Europe: Collected Studies. Ed. Victor Spinei. Englishlanguage monograph,1 contains eight arti Bucureşti: Editoru Academiei Romăne, Brăila: cles. In “The First Mongol Raids against the Volga Editura Istros a Muzueului Brăilei, 2014. 298 Bulgars” (1523), Zimonyi confirms the report of pp. Abbreviations. ibnAthir that the Mongols, after defeating the his anthology by the distinguished Hungarian Kipchaks and the Rus’ in 1223, were themselves de Tscholar of the University of Szeged István Zi feated by the Volga Bolgars, whose triumph lasted monyi contains twentyeight articles, twentyseven only until 1236, when the Mongols crushed Volga of them previously published between 1985 and Bolgar resistance. 2013. Seventeen are in English, six in Russian, four In “Volga Bulgars between Wind and Water (1220 in German, and one in French, demonstrating his 1236)” (2533), Zimonyi explores the preconquest adherence to his own maxim that without transla period of BulgarMongol relations further. -

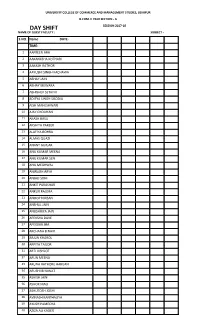

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

Price List of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014

Price list of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014 DECCAN COLLEGE POST-GRADUATE AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Deemed University) PUNE 411 006 (INDIA) (1) Terms & Conditions of Sale (This cancels our previous trade terms) Terms 1. Actual postal and packing charges to all orders received from outside India. 2. Postal and packing charges to be borne by the person/institution for all the orders upto Rs. 1000/- in India. 3. Free postal and packing charges to the orders above Rs. 1000/- one time. 4. No discount to individual buyers. 5. 20% discount on all the orders upto Rs. 500/-. 6. 25% discount on all the orders which exceeds Rs. 500/-. 7. Except educational and governmental institutions, books will be supplied ONLY on receipt of Advance Payment against Proforma Invoice. Conditions 1. Out-station buyers should remit the amount, either by M.O. or by Demand Draft drawn on any Nationalized Bank at Pune in the name of ‘Deccan College, Pune’. 2. For the convenience of both the supplier and the buyer and for the early delivery of the books, the books are usually supplied by Registered Book Post marked ‘Printed Books’. 3. Only bulk supply is made by roadways. 4. Books are supplied at buyer’s risk and supplier is not responsible for the books damaged, lost, etc., in transit as also for the delay in delivery of the books. 5. Books once sold and dispatched are not accepted back for any reason on exchanged for other parts. 6. Errors and omissions on the part of the supplier are accepted. 7. Books are not supplied by V.P.P. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Banni Grassland

Symposium on Banni Grassland Report of Symposium on Banni Grassland 4th & 5th March 2011 Symposium Sponsors Gujarat State Forest Department, GoG, Gandhinagar Gujarat Mineral Development Corporation, GoG, Gandhinagar Commissionerate of Rural Development, GoG, Gandhinagar Organized By Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE) Post Box # 83, Mundra Road Bhuj – 370 001, Kachchh, Gujarat, India Website: www.gujaratdesertecology.com Gujarat Institute of Desert Ecology (GUIDE), Bhuj-Kachchh Symposium on Banni Grassland Background Banni region has a very fascinating history, geography, diversity of flora and fauna, highly nutritive grasses; rich cultural heritage of Maldhari (Cattle breeders) communities, unrivalled embroidery work and other handicrafts, soul-touching folk and Sufi music, earthquake resistant mud houses Bhunga, traditional fresh water reservoirs Virda, traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and animal breeding and last but never the least, drought tolerant highly productive livestock - the very base of survival of Maldharis. Banni is perhaps the only largest stretch (2617 km2) of grasslands in India, which was once the „finest grassland‟ of Asia. It is located between Kachchh mainland and Greater Rann of Kachchh in the north western part of Gujarat State of India. The region is believed to have formed due to seismic activities and marine processes operating in the north along with fluvial deposition by the Indus and other rivers during the Vedic times. These virtues of Banni have always attracted scientists, sociologists, naturalists and tourists. Livestock is the mainstay of inhabitants of Banni, constituting major bulk of their assets. Despite tough survival conditions, Banni buffaloes are the most productive cattle in India and are recently recognised by „National bureau of Animal Genetic Resources‟ as 11th distinct breed of the nation. -

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report Submitted to Mr. Rahul Gandhi General Secretary All India Congress Committee New Delhi BY Dr. Chandrashekar Naik Dr.D Paramesha Naik B.E,M.Tech,M.B.A,M.Phil Ph.D M.Sc, M.Phil, Ph.D, FISEC Congress & Banjara – Activist Congress & Banjara – Activist Mobile: +91-9379945100 Mobile: +91-9844250997 [email protected] [email protected] 2012 About Banjaras The Banjaras are the largest and historic formed group in India and also known as Lambadi or Lambani. The Banjara people are a people who speak lambadi or Lambani. All gypsy languages are linked linguistically, stemming from ancient Sanskrit and belonging to the North Indo-Aryan language family. Lambadi is the heart language of the Banjara, but it has no written script. The Banjara speak a second language of the state they live in and adopt that script. They are listed under 53 different names. Historically, these are the root Gypsies of earth. During the British colonial rule, these gypsy nomads of India were given the name Banjara, but they call themselves Ghor. The Banjaras are a colourful, versatile and one of the largest people groups of India, inhabiting most of the districts in India. The Banjara are a sturdy, ambitious people and have a light complexion. The Banjara were historically nomadic, keeping cattle, trading salt and transporting goods. Most of these people now have settled down to farming and various types of wage labour. Their habits of living in isolated groups away from other, which was a characteristic of their nomadic days, still persist. -

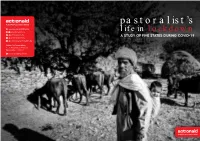

Pastoralist's Life in Lockdown

pastoralist’s www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia life in lockdown @actionaid_india A STUDY OF FIVE STATES DURING COVID-19 @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association, R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 2 3 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 Pastoralist’s Life in Lockdown A study of five States during COVID-19 First Published September, 2020 Some rights reserved This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for non- commercial purposes under the same original license terms. Photograph Credits Anu Verma and Biren Nayak Edited by Joseph Mathai Layout by M V Rajeevan Cover Page by Nabajit Malakar Published by Natural Resources Knowledge Activist Hub www.actionaidindia.org @actionaidindia @actionaid_india @actionaidcomms @company/actionaidindia ActionAid Association R - 7, Hauz Khas Enclave, New Delhi - 110016 +911-11-4064 0500 Printed at: Baba Printers, Bhubaneswar CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgements vii List of Abbreviations ix Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Understanding pastoralism and pastoral occupation 3 Pastoral communities in India 7 Chapter 2: Impact of COVID-19 on Pastoralists: An Overview 11 Methodology 14 Chapter 3: Study Findings 17 Challenges in moving with herd during lockdown 17 Changes in time of migration 19 Mobility of pastoral communities during lockdown 22 Change in