Inventing to Preserve: Novelty and Traditionalism in the Work of Stompin' Tom Connors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Waiting for a Train” in Canada

“Waiting for a Train” in Canada Tim Rogers, University of Calgary With considerable help from Roy Forbes, Fred Isenor, Michael Kolonel, John Leeder, Giselle and Keith Smith, Frank Watson, and Ted Rowe It was a good jam despite my guitar being outnum- square dances, and in sessions whenever he found bered two to one by banjos. At one point I sang Jim- like-minded musicians. (Leeder 2013) mie Rodgers’s “Waiting for a Train” (a.k.a. “All Around the Water Tank”). I’d known this song for Whatever the source, Gerry knew “Waiting for a years, but had recently dusted it off after hearing Roy Train” in waltz time. Forbes’s fine version.1 Waiting for a Train (Jimmie Rodgers’s version) All around the water tank, waiting for a train, A thousand miles away from home, sleeping in the rain; I walked up to a freight man to give him a line of talk, He said, “If you’ve got money, I’ll see that you don’t walk”; “I haven’t got a nickel, not a penny can I show”, “Get off, get off, you railroad bum,” and he slammed the boxcar door. Well, they put me off in Texas, a state I dearly love, Wide open spaces around me, moon and stars above; Nobody seems to want me or lend me a helping hand, I’m on my way from Frisco, going back to Dixieland; My pocket book is empty and my heart is full of pain, I’m a thousand miles away from home, waiting for a train. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Wilf Carter 24 Great Songs- " the Golden Years" Mp3, Flac, Wma

Wilf Carter 24 Great Songs- " The Golden Years" mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: 24 Great Songs- " The Golden Years" Country: Australia Released: 1976 Style: Honky Tonk MP3 version RAR size: 1528 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1831 mb WMA version RAR size: 1161 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 681 Other Formats: ADX AHX AA MPC DTS WAV MP2 Tracklist A1 Theres A Blue Bird On Your Window Sill A2 This Ole House A3 It Is No Secret A4 Hold On Little Doggie A5 My Nova Scotia Home A6 (When It's Apple Blossom Time) In Annapolis Valley A7 You Are My Sunshine A8 When It's Springtime In The Rockies A9 Beautiful Brown Eyes A10 Goodnight Irene A11 Yellow Rose Of Texas A12 The Old Rugged Cross B1 Nobody's Darlin' But Mine B2 Blue Canadian Rockies B3 Red Wing B4 The Yodelling Swiss B5 My Little Two Acre Farm B6 There's A Love Knot In My Lariat B7 My Swiss Moonlight Lullaby B8 It Makes No Difference Now B9 Mockin' Bird Hill B10 Shoo Shoo Shoo Sha-La-La B11 He'll Have To Go B12 The Pub With No Beer Companies, etc. Manufactured By – RCA Limited Australia and New Zealand Notes Made from masters of RCA Records Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 24 Great Songs- "The K-Tel International WC 316 Wilf Carter WC 316 Canada 1976 Golden Years" (LP, Comp) (Canada) Related Music albums to 24 Great Songs- " The Golden Years" by Wilf Carter Wilf Carter - Walls Of Memory Wilf Carter - The Dynamite Trail ! - The Decca Years, 1954-58 Joe Loss And His Orchestra - Shoo Shoo Baby / In The Bridge Of Avignon Gene Autry - His Golden Hits Jimmy Boyd - Shoo-Fly Pie And Apple Pan Dowdy / Playmates SHOO FLY PI - SHOO FLY PI Peter Noone - Shoo Be Doo Ah Varsity Singers - Songs Of America Donn Reynolds - The Blue Canadian Rockies Jim Gussey - It's No Secret / Mockin' Bird Hill. -

16Th ANNUAL HANK SNOW TRIBUTE

The Official MONewsletter of The FriendsV ofIN’ Hank Snow Society VOLUMEON 12 #1 SUMMER 2006 “SNOW NEWS IS GOOD NEWS” ★ 16th ANNUAL HANK SNOW TRIBUTE ★ It seems like only yesterday that we were at the 15th Annual Hank Snow Tribute, greeting old friends, making new Father’s Day Outdoor Country Music Fest ones, listening to fantastic music on the stage and taking part in the jams. We are all looking forward to this year’s event, which will be here before we know it! We are pleased to have Kayton & Iva Lee Roberts and Roger Carroll returning this year from Nashville. Other special guests making the trip from Tennessee this year include Bob Burris, co-author of “The Hank Finale at 2005 Father's Day Outdoor Country Music Fest, featuring Jim Snow Story”, as well Crowell, Paul Moulaison, Wayne Snyder, Gibby Munroe, Dale Verge, Joyce as his brother-in-law, Seamone, Gordie Giles, Chet Brown, Karl Levy, Carl Dalrymple and Carol Joe Ownbey, who will Penney. be performing. Bob will be available to The 5th Annual Father’s Day Outdoor Country Music sign specially priced Fest will be held on Friday, June 16th from 7:00 pm to 10:00 books and share a pm, and Saturday, June 17th, from 10:00 am to 8:00 pm. story or two. Making There will be DRY CAMPING available for those who want the trip from Arkansas to camp out for the festivities. We have events planned for to perform will be all ages, including live entertainment by great performers from Smilin' Ivan Dorey, pictured here at a recent David Redford, a across Nova Scotia and New Brunswick under the big tent, Hank Snow Tribute, sadly passed away long-time Hank Snow January 1, 2006. -

Download the Alberta Beef Magazine As a Pdf File

INDUSTRY NEWS INTEREST FREE MONEY print in Western Canadian agricul - industry hits the 15 billion-gallon NOW AVAILABLE ture in its four short years. mark - a production level that would yield approximately 17 mil - On behalf of Agriculture and lion tons of DDGS per year. Accord - Agri-Food Canada, Feeder Associ - ETHANOL BOOM ing to the U.S. Grains Councils ations of Alberta Ltd. has report, this remarkable level of pro - announced they have signed on to The extraordinary growth of the duction is expected to create inter - deliver the $100,000.00 Interest U.S. ethanol industry is bringing national market opportunities that Free Cash Advance & Interest with it the production of massive will prompt beef, dairy, swine and Rebate Programs. quantities of distillers grains poultry producers, as well as feed Under the Advance Payment (DDGS). Based on the projections of manufacturers, around the world to Program (APP), individuals and top industry analysts, this pre-cellu - take advantage of the sheer volume, independent farming operations losic ethanol build-out will continue price and quality of this product. are limited to a maximum cash until the corn dry-mill dominated advance of $400,000.00 in total advances during any one produc - tion period. The federal govern - ment pays the interest on the first $100,000.00 of a cash advance Rainalta Simmentals issued to a producer. Rainalta Simmentals Producers have a maximum of an 18 month production period to JJ Anchor Anchor Simmentals Simmentals repay their cash advances or as their agricultural product is sold. The UluruUluru Red Red Angus Angus 2007-2008 Advance Payments Pro - gram (APP) production period runs from Aug. -

Points-West 2004.03.Pdf

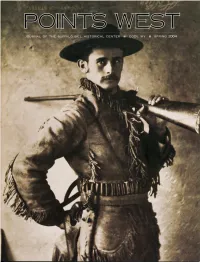

.-.-F- l.r, t. 1ri;, i\ $i :jili o 200,1 Buflalo Bill Historical Center. Wrilten permission is required to All images contained herein, unless noted otherwrse, copy, reprint, or distribute Points west materials jn any medium or format. All phorographs in Polnrs wesl are Buflalo Bill Historical Cenler are associated with the wtldli,fe and western Heroes: photos unless otherwise noted. Address correspondence to Editor, Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor exhibition. Points West, Buffalo Bill Hjslorical CenteL 720 Sheridan Avenue. Cody, wyoming 82411 at [email protected]. Editor: Thom Huge Wildli;fe and Western Heroes : Alexander Phimister Proctot, Designer: Jan Woods'Krier/PRODESIGN Sculptor is organized by the Amon Carter Museum, Fort Production Coordinator Rae Eckley Photography Stalf: Chris Gimmeson Worth, Texas, and is made possible in part by Mr. and Sean campbell Mrs. Sebert L Pate, the Mary Potishman Lard Trust, and Points west is published quarterly as a benelit ol membership in the The Bulfalo Bill Historical center. For membership information contact: the Ruth and Vernon Taylor Foundation. companron Kathy Mclane, Director of Membershjp publication is generously supported by a gift lrom the Buflalo Bill Historical center 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, WY 82414 Proctor Foundation, Poulsbo, Washington. kathym @bbhc. org 307 .578.4A32 The Buffalo Bill Historical Center is a private, non-profit, educational institution dedicated to preserving and inlerpreting the natural and culrural history of the American West. Founded jn 1 91 7, the Historical Cover. Photographer Unknown. Phoiograph ol Alexander center js home to the Buffalo Bill Museum, whitney Gallery of Western Phimister Proctor, ca. 1880. -

17Th Annual Hank Snow Tribute to Feature Exciting

The Official MONewsletter of The FriendsV ofIN’ Hank Snow Society VOLUMEON 13, #1• SPRING 2007 “SNOW NEWS IS GOOD NEWS” 17TH ANNUAL HANK SNOW TRIBUTE TO FEATURE EXCITING LINEUP It is hard to believe that we have been holding this event for as well as singer/songwriter JD Clarke from Elmsdale, NS, who 17 years! It has become a yearly reunion where we reconnect received national and international airplay in 2007 with his with old friends and make new ones while we listen to “Somethin’ Bout You” and who also won the 2006 Music Nova fantastic music on the stage and take part in the jams. We are Scotia Country/Bluegrass recording of the year award. Joining really looking forward to this year’s event, which will be here them will be singer/songwriter Ryan Cook of Yarmouth, NS. before we know it! Ryan and his band Sunny Acres are a well sought after up-and- We are excited to have a coming act with a very busy schedule. Rounding out the circle we very special guest joining have Jodi Faith, all the way from Lefleche, Saskatchewan. Jodi us from Nashville this is an award-winning vocalist and songwriter who has performed year. George Hamilton across Canada from coast to coast as well as in the US. She is IV will be performing on currently experiencing radio airplay in 38 countries around the Thursday night as well as world. As always, grab that first coffee and join us bright and hosting our Gospel Concert early Saturday morning and support this most amazing group of on Sunday morning. -

Alberta Mix Tape

Alberta Mix Tape These are songs ABOUT Alberta, not necessarily by Albertans. For you to enjoy while out doing Alberta history or just to enjoy, the Historical Society of Alberta has put together this list of songs. Who knows, as you listen to some great music, you may even learn more about the history and people of this phenomenal province. Note: we have been able to find and listen to 200 or so of these songs through CDs and downloadable sources but some were never recorded and, indeed, may not have been sung or played in many years. Some of these songs are, today, simply sheet music to be found in archives and libraries across the province. For the purposes of our list, a song must be about an Alberta place, person or event (in whole or in part). We have given the list twice – first time by song title (complete list), second time by artist. If you know of songs missing from the list, please send them our way: 403-261-3662 or [email protected]. Alberta Mix Tape – Songs of Alberta Historical Society of Alberta Alberta Mix Tape – by Song Song Artist 1942 Terry Morrision 16 Wheels Al Owchar A Butterfly Landed John Spearn A Cowboy's Heart Sean Hogan Ain't Gonna Hobo No More Johnny Cash Alberta Jess Lee Alberta Michael Bernard Fitzgerald Alberta Blue Lana Floen Alberta Border Diamond Joe White Alberta Bound Gordon Lightfoot Alberta Bound Paul Brandt Alberta Champion Waltz Wally Knash Alberta Charm Donna Konsorado Alberta Christmas Morning Gord Bamford Alberta Crude Laura Vinson Alberta Crude Tim Hus Alberta Dreams Alberta Eyes Braden -

Is There an Alberta Folk Music? 1

IS THERE AN ALBERTA FOLK MUSIC? 1 T. B. ROGERS A number of occupations are especially conducive to the development of a folk-music tradition: for example, lumberjacks, railroaders, miners, voyageurs, cowboys and homesteaders. Aggregations of men involved in these activities tend to develop folk-music traditions which typically borrow heavily from older forms and eventually evolve into distinct musical traditions (Fowke, 1970 is a particularly good example of this). It follows that regions with such occupational groups should be fertile grounds for the folklore collec tor. Viewed from this perspective, it is somewhat surprising that very little English-language folk music has been uncovered in Alberta. English-speaking peoples in this part of Canada show considerable populations of cowboys, homesteaders, and railroaders. As these are “folk-music prone” groups you would expect some folk-music tradition in this region. However, a review of the available resources suggests that very little material has been documented. This paper will explore the apparent lack of folk music of Alberta and argue that there is an untapped folk-music tradition in that province. A number of sources converge on the popular view that Alberta does NOT have an English-speaking folk music. A review of the published works of Cana dian folk music reveals no collections dealing solely with Alberta. Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia have localized collections in print or on record while Alberta does not. Considering available recorded archives (field recordings, collection tapes, etc.) an Alberta collection has yet to be found. While some work has been done,2 there is no record of substantial scholarly activity orientated toward Alberta English-language folk music. -

Why Does Country & Western Music

NEW ENGLAND COUNTRY & WESTERN MUSIC: SELF-RELIANCE, COMMUNITY EXPRESSION, AND REGIONAL RESISTANCE ON THE NEW ENGLAND FRONTIER BY CLIFFORD R. MURPHY B.A. GETTYSBURG COLLEGE, 1994 M.A. BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2005 SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE PROGRAM IN MUSIC: ETHNOMUSICOLOGY AT BROWN UNIVERSITY. PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2008 © 2008 CLIFFORD R. MURPHY This dissertation by Clifford R. Murphy is accepted in its present form by the Department of Music as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. (signed and dated copy on file at Brown University) Date_______________ _________________________ Jeff Todd Titon, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date_______________ __________________________ Jennifer Post, Reader Date_______________ __________________________ Paul Buhle, Reader Date_______________ __________________________ Rose Subotnik, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date_______________ __________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Clifford R. Murphy was born in Ridgewood, New Jersey in 1972 and was raised in New Hampshire in the towns of Durham and Newmarket. Cliff learned to play guitar at age 16, graduated from Newmarket High School in 1990, and attended Gettysburg College where he majored in History and English. Following graduation in 1994, Cliff returned to New Hampshire and spent the next nine years working as a singer, songwriter, and rhythm guitarist in the internationally -

Performing Country Music in Canada

Stompin’ Grounds: Performing Country Music in Canada by Erin Jan Elizabeth Schuurs A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Erin Jan Elizabeth Schuurs, September, 2019 Abstract STOMPIN’ GROUNDS: PERFORMING COUNTRY MUSIC IN CANADA Erin Jan Elizabeth Schuurs Advisor: University of Guelph, 2019 Dr. Catharine Anne Wilson Country music in Canada and its different geographical regions existed within a transnational set of fictions which were shared by a great many North Americans. Industry members, performers, and fans have relied upon the markers of sound, rurality, masculinity, and later “Canadian-ness” to prove the music’s “authenticity.” More than anything, what is noteworthy about country music is not that it is a continuation of “authentic” folk practices, but the music’s ability to continually reinvent itself while maintaining these fictions. By examining five distinct country music performers who had active careers in Canada – Wilf Carter, Earl Heywood, Don Messer, Stompin’ Tom Connors, and Gordon Lightfoot – this study examines how Canadian country music artists between the 1920s and the 1970s created “authentic” images. This was achieved through song lyrics and instrumentation, visual markers such as cowboy hats, and through interviews, autobiographies, photographs, and other publicity materials. iii “Country music is three chords and the truth.” -Howard Harlan “Music is the emotional life of most people.” -Leonard Cohen iv Acknowledgements It takes a village to write a dissertation and I am forever grateful to the many people who formed the village it took to see this dissertation completed. -

S Only-Music Weekly

CANADft: S ONLY- MUSIC WEEKLY Week Ending February 4th. 196l 15 CENTS ·:·.. :~~ .. ·. :!'' Vo lume 6, No. 23 TOP MALE BARRY ALLEN -- Capitol 2. BOBBY CURTO LA - Tartan THE VOCALIST 3. D.C.THOMAS - Roman TOP FEMALE 2. LYNDA LAYNE - Red Leaf VOCALIST CATHERINE MCKINNON --·Arc 3. MARTI SHANNON - RCA Victor ANNUAL MOST PRO.MISING 2. BOBBY KRIS - Columbia MALE VOCALIST JIMMY DYBOLD - Red Leaf 3. BOB HARRINGTON - Reo MOST PROMISING 2. DEBBIE ·LORI KAYE - Columbla FEMALE VOCALIST LYNDA LAYNE -- Red Leaf 3. GILLIAN RUSSELL - New Syndr~me TOP INSTRUMENTAL 2. BRIAN BROWNE TRIO - RCA Victor GROUP WES DAKUS -- Capitol 3. BUTTERFINGERS - Red Leaf TOP VOCAL 2. GUESS WHO - Quality INSTRUMENTAL GROUP STACCATOS -- Capitol 3. UGLY DUCKLINGS - Yorktown TOP FEMALE 2. WILLOWS - MGM VOCAL GROUP ALLEN SISTERS - Quality 3. ARBORFOLK - Unk TOP FOLK 2. IAN & SYLVIA - Vanguard GROUP 3'S A CROWD__:. Epfo 3. MALKA & JOSO - Capitol TOP FOLK 2. MARTI SHANNON - RCA Victor SINGER GORDON LIGHTFOOT -- United Artists 3. CATHERINE McKINNON - Arc BEST PRODUCED LET'S RUN AWAY -- Capitol 2. I SYMBOLIZE YOU - Columbia SINGLE Stacc atos (Produced by Sandy Gardiner) 3. BRAINWASHED - Roman TOP NATIONAL 2. BOB MARTIN - Columbia PROMOTION MAN PAUL WHITE - Capitol r 3. LEE FARLEY - Quality TOP REGIONAL 2. CHARLIE CAMILLERI - Columbia PROMOTION MAN AL MAIR - Apex 3. ED LAWSON - Quality TOP CANADIAN 2. CAPITOL RECORDS (Canada) LTD. CON TENT COMPANY RED LEAF RECORDS 3. COLUMBIA RECORDS OF CANADA TOP RECORD 2. COLUMBIA RECORDS OF CANADA COMPANY CAPITOL RECORDS CCanadal LTD. 3. QUALITY RECORDS LIMITED TOP COUNTRY 2. IRWIN PRESCOTT - Melbourne SINGER MALE GARY BUCK - Capitol 3.