A Tall Order Jason Graves Scores a Dark Adventure in the Order: 1886

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

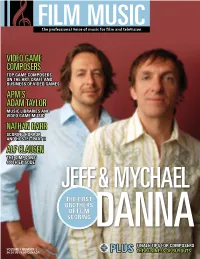

Video Game Composers Apm's Adam Taylor Nathan Barr

FILM MUSIC pdalnkbaooekj]hrke_akbiqoe_bknbehi]j`pahareoekj VIDEO GAME COMPOSERS TOP GAME COMPOSERS ON THE ART, CRAFT AND BUSINESS OF VIDEO GAMES APM’S ADAM TAYLOR MUSIC LIBRARIES AND VIDEO GAME MUSIC NATHAN BARR SCORING HORROR AND HOSTEL: PART II ALF CLAUSEN THE SIMPSONS’ 400TH EPISODE JEFF & MYCHAEL THE FIRST BROTHERS OF FILM SCORING DANNA FINALE TIPS FOR COMPOSERS RKHQIA3JQI>AN/ 2*1,QO 4*1,?=J=@= + PLUS THE BUSINESS OF BUYOUTS RE@AKC=IA?KILKOANO 5GD8NQKCNE (".& $0.104*/( BY PETER LAWRENCE ALEXANDER WITH GREG O’CONNOR-READ 14 ! filmmusicmag.com In a rapidly changing technological environment that’s highly competitive, composers the world over are looking for new opportunities that enable them to score music, and for a livable wage. One of the emerging arenas for this is game scoring. Originally the domain of all synth/sample scores, game music now uses full orchestras, along with synth/sample libraries. To gain a feel for this industry, and to help you, the reader, decide if game scoring is something you want to pursue, Film Music Magazine has established an unprecedented panel in print: six top video game composers with varying styles and musical tastes, plus top game composer agent Bob Rice of Four Bars Intertainment. As you read the interviews, it will become quickly apparent that while there are many Let’s pretend that you’ve started a new music school course just for game composers. Given your experience, similarities between film and TV, and game what would you insist every student learn to master, and scoring, one major difference arises that is why? Rod Abernethy and Jason Graves:E^Zkgrhnklmk^g`mal literally within the mind of the composer. -

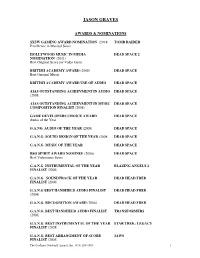

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (201 4) TO MB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Sco re HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD USE OF AUDIO DEAD SPACE AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWAR D DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AUDIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING ANGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRAC K OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A. N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIST KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. BEST CHORA L PERFORMANCE KING ARTHUR FINALIST (2004) G.AN.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR THE HOBBIT WINNER (2003) G.AN.G. -

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (2014) TOMB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Score HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD USE OF AUDIO DEAD SPACE AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWARD DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AUDIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (20 08) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING ANGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A.N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIS T KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. BEST CHORAL PERFORMANCE KING ARTHUR FINALIST (2004) G.AN.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR THE HOBBIT WINNER (2003) G.AN.G. -

![Moss Soundtrack Download]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1410/moss-soundtrack-download-2551410.webp)

Moss Soundtrack Download]

Moss Soundtrack Download] Download ->->->-> http://bit.ly/2QOjxmX About This Content A melodic and playful adventure score conveys Quill's story in Moss from her perspective by employing small and intimate- sounding instruments – flute, oboe, Celtic harp, English hammered dulcimer, acoustic guitar, and classical violin – all composed, arranged and produced in a pastoral soundscape with enchanting Waltz-esque flair. 1 / 9 11 Tracks: 1) Dear Reader (5:51) 2) Twofold (1:50) 3) The Clearing (6:00) 4) Thickets and Bloom (5:41) 5) Legends Old and New (5:54) 6) Last Respite (5:38) 7) Cinder Skies (5:22) 8) A Different Story (5:13) 9) Sarffog's Domain (6:55) 10) I'm Not Alone (3:38) 11) Home To Me (5:30) Music composed by: Jason Graves Mixed by: Jason Graves and Stephen Hodde Mastered by: Joel Yarger at Sony Interactive Entertainment America Cover design by: Corinne Scrivens Solo performances by: - Alan Atkinson - vocals - Jeff Ball - violin - Kristin Naigus - flute, oboe, English horn - Maukah - lead vocals on "Home To Me" - Jason Graves - acoustic guitar, bass, ukulele, accordion, Celtic harp, hammered dulcimer, Native American flute, percussion, drums Special thanks to: - Valve (Marcus Egan, Nathaniel Blue, Dave Feise) - Sony Interactive Entertainment America (Chuck Doud, Joel Yarger, Peter Scaturro) Jason Graves is an Academy Award-winning (BAFTA) composer who has brought his passion for music to projects such as MOSS (POLYARC), FAR CRY PRIMAL (UBISOFT), UNTIL DAWN (SONY), TOMB RAIDER (SQUARE ENIX) and DEAD SPACE (EA). He is particularly enthusiastic about illustrating a project’s story and character arcs through the power of music. -

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (2014) TOMB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Score HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD USE OF AUDIO DEAD SPACE AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWARD DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AU DIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING A NGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A.N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIST KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. BEST CHORAL PERFORMANCE KING ARTHUR FINALIST (2004) G.AN.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR THE HOBBIT WINNER (2003) G.AN.G. -

Interviews with Jason Graves, Garry Schyman, Paul Gorman and Michael Kamper

HOST 5 (1) pp. 127–144 Intellect Limited 2014 Horror Studies Volume 5 Number 1 © 2014 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/host.5.1.127_1 Helen r. MitcHell The University of Hull Fear and the musical avant‑garde in games: interviews with Jason Graves, Garry schyman, Paul Gorman and Michael Kamper AbstrAct Keywords If you have ever experienced the cold chill of fear when watching a film or playing avant-garde music a video or computer game, it is highly probable that your responses have been interview manipulated by composers exploiting the musical resources of modernism, experi- horror mental music and the avant-garde. Depictions of fear, horror, amorality, evil and fear so on, have come to be associated with these sound worlds, particularly within the film realm of popular culture. A number of game titles and franchises have emerged game in recent years, which exploit these musical associations, exploring their creative potential as vehicles of fear and horror within the context of interactive game-play. Two composers associated with this approach are Jason Graves (Dead Space fran- chise) and Garry Schyman (Bioshock franchise, Dante’s Inferno). This article explores perceived links between avant-garde music (as defined in ‘populist’ rather than musicological or historical terms, as a ‘catch-all’ phrase for twentieth-century music exploiting experimental techniques, modernism and atonality) and depictions of horror and fear through interviews with Graves and Schyman. Further questions 127 HOST_5.1_Mitchell_127-144.indd 127 3/25/14 8:42:28 AM Helen R. Mitchell 1. The term ‘Avant- are posed to Paul Gorman (audio director – Dante’s Inferno) and Michael Kamper garde’ is defined here in ‘populist’ terms (audio director – Bioshock 2) to contextualize the discussion by demonstrating the as something of a significant creative influence of audio directors in guiding the musical approach ‘catch all’ phrase for taken by game composers. -

An Exploration of Dissonant Player Experiences

Atmosphere & Challenge An Exploration of Dissonant Player Experiences by Giovanni Ribeiro A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Applied Science in Systems Design Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Giovanni Ribeiro 2019 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION This thesis consists of material all of which I authored or co-authored: see Statement of Contributions included in the thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii STATEMENT OF CONTRIBUTIONS This thesis consists of two papers that were co-authored by myself, my supervisor, Dr. Lennart Nacke, and three others: Towards a Physiological Profile of Rage Quitting By: Giovanni Ribeiro, Rina Wehbe, and Lennart E. Nacke Atmosphere: The Effect of Thematic Audio Fit on Player Experience By: Giovanni Ribeiro, Katja Rogers, Thomas Terkildsen, and Lennart E. Nacke Dr. Nacke, Rina Wehbe, Katja Rogers, and Thomas Terkildsen provided research guidance, advice, and proofreading. Ms. Rogers and Ms. Wehbe were invaluable in the experimental design and research ideation process of their respective projects and Mr. Terkildsen contributed to the evaluation and statistical analysis of physiological data. Surya Banerjee (Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science) helped me decide what the most appropriate statistical tests to run were. iii ABSTRACT Dissonance means an unusual combination of any two things. Two dissonant experiences in video games which could lead to undesirable player states are thematic dissonance and difficulty dissonance. Thematic dissonance potentially annoys players by breaking the atmosphere, and difficulty dissonance by preventing players with low skill from progressing past unbalanced challenges, resulting in rage-quits. -

Technical Program Template

AAEESS113311 st CCoonnvveenn ttiioonn PPrroo ggrraamm October 20 – 23, 2011 Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, New York, NY, USA The AES has launched a new opportunity to recognize room decay time for bass frequencies. We student members who author technical papers. The Stu - develop the theory for a point active absorber dent Paper Award Competition is based on the preprint immersed in the acoustic source field from a manuscripts accepted for the AES convention. point source. This would apply to normal loud - A number of student-authored papers were nominated. speakers used as either sources or absorbers at The excellent quality of the submissions has made the frequencies below about 300 Hz, where they act selection process both challenging and exhilarating. as points. The result extends the theory of Nel - The award-winning student paper will be honored dur - son and Elliott for a point absorber interacting ing the Convention, and the student-authored manuscript with a plane wave. An extra term occurs that has will be considered for publication in a timely manner for little net effect when averaged over frequency or the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society . distance. In rooms such cancellation occurs due Nominees for the Student Paper Award were required to the varying distances from all the source to meet the following qualifications: images to the absorber. Impulse responses in (a) The paper was accepted for presentation at the several small rooms were measured from a AES 131st Convention. source and an absorber loudspeaker to both a (b) The first author was a student when the work was few listening microphones and a microphone conducted and the manuscript prepared. -

Jason Graves

JASON GRAVES AWARDS & NOMINATIONS G. A. N. G. AWARD (2019) MOSS Best Music for an Indie Game HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA THE ORDER: 1886 NOMINATION (2015) Best Original Score for Video Game SXSW GAMING AWARD NOMINATION (2014) TOMB RAIDER Excellence in Musical Score HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA DEAD SPACE 2 NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Video Game BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (BAFTA) (2008) DEAD SPACE Best Original Music BRITISH ACADEMY AWARD (BAFTA) USE OF DEAD SPACE AUDIO AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN AUDIO DEAD SPACE (2008) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC DEAD SPACE COMPOSITION FINALIST (2008) GAME DEVELOPERS CHOICE AWARD DEAD SPACE Audio of the Year G.A.NG. AUDIO OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. SOUND DESIGN OF THE YEAR (2008) DEAD SPACE G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR DEAD SPACE BSO SPIRIT AWARD NOMINEE (2006) DEAD SPACE Best Videogame Score G.A.N.G INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR BLAZING ANGELS 2 FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G. SOUNDTRACK OF THE YEAR DEAD HEAD FRED FINALIST (2006) G.A.N.G BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST DEAD HEAD FRED (2006) G.A.N.G. RECOGNITION AWARD (2006) DEAD HEAD FRED G.A.N.G. BEST HANDHELD AUDIO FINALIST TRANSFORMERS (2006) The Gorfaine/ Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 JASON GRAVES G.A.N.G. BEST INSTRUMENTAL OF THE YEAR STAR TREK: LEGACY FINALIST (2005) G.A.N.G. BEST ARRANGMENT OF SCORE JAWS FINALIST (2005) AIAS OUTSTANDING ACHIEVMENT IN MUSIC RISE OF THE KASAI COMPOSITION FINALIST (2004) G.A.N.G. MUSIC OF THE YEAR FINALIST KING ARTHUR (2004) G.A.N.G. -

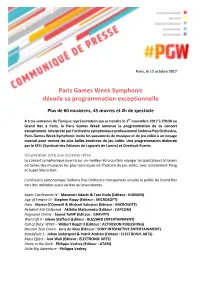

Paris Games Week Symphonic Dévoile Sa Programmation Exceptionnelle

Paris, le 12 octobre 2017 Paris Games Week Symphonic dévoile sa programmation exceptionnelle Plus de 60 musiciens, 45 œuvres et 2h de spectacle A trois semaines de l’unique représentation qui se tiendra le 1er novembre 2017 à 20h30 au Grand Rex à Paris, la Paris Games Week annonce la programmation de ce concert exceptionnel. Interprété par l’orchestre symphonique professionnel Sinfonia Pop Orchestra, Paris Games Week Symphonic invite les passionnés de musique et de jeu vidéo à un voyage musical pour revivre les plus belles émotions du jeu vidéo. Une programmation élaborée par le SELL (Syndicat des Editeurs de Logiciels de Loisirs) et Overlook Events. Un premier acte aux accents rétro Le concert symphonique ouvrira sur un medley rétro qui fera voyager les spectateurs à travers certaines des musiques les plus iconniques de l’histoire du jeu vidéo, avec notamment Pong et Super Mario Kart. L’orchestre symphonique Sinfonia Pop Orchestra transportera ensuite le public du Grand Rex vers des mélodies aussi variées qu’envoutantes. Super Castlevania IV - Masanori Adachi & Taro Kudo (Editeur : KONAMI) Age of Empire III - Stephen Rippy (Editeur : MICROSOFT) Halo - Martin O'Donnell & Michael Salvatori (Editeur : MICROSOFT) Resident Evil Outbreak - Akihiko Matsumoto (Editeur : CAPCOM) Ragnarok Online - Sound TeMP (Editeur : GRAVITY) Warcraft II - Glenn Stafford (Editeur : BLIZZARD ENTERTAINMENT) Call of Duty: WWII – Wilbert Roget II (Editeur : ACTIVISION PUBLISHING) Horizon Zero Down - Joris de Man (Editeur : SONY INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT) Battlefield 1 - Johan Söderqvist & Patrik Andrén (Editeur : ELECTRONIC ARTS) Mass Effect - Jack Wall (Editeur : ELECTRONIC ARTS) Alone in the Dark - Philippe Vachey (Editeur : ATARI) Little Big Adventure - Philippe Vachey Titres culte et représentations inédites rythmeront le deuxième acte La suite du voyage musical Paris Games Week Symphonic se voudra aussi éclectique que lyrique avec des Bandes originales devenues culte, dont certaines n’ont encore jamais été jouées devant un puBlic dans le cadre d’un concert. -

3 Die Aufgabe Und Wirkung Von Musik Und Sound in Videospielen ...14

Hochschule Offenburg Medien- und Informationswesen Bachelorarbeit Sound und Musik in Videospielen: Eine Studie zur Auswirkung auf die Emotionen der Spieler Vorgelegt von: Julia Seibicke Matrikelnummer: 176770 Betreuer: Prof. Dr. phil. Oliver Korn Zweitbetreuer: Michael Blatz, B.Sc. Hochschule Offenburg offenburg.university Abstract Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit der Frage, wie Musik und Soundeffekte in Videospielen die Emotionen der Spieler und ihre Meinung zum Spiel beeinflussen. Um diese Frage zu beant- worten soll nach einer kurzen Einleitung in die Entwicklung der Videospielmusik und die Emo- tionsforschung eine Studie durchgeführt werden, bei der Probanden das Spiel Pinstripe mit beziehungsweise ohne Musik spielen und anschließend einen Fragebogen ausfüllen. Beim Spielen wird außerdem ihr Puls gemessen. Auch werden Zusammenhänge zwischen Big Five- Persönlichkeitsmerkmalen, den Spielertypen nach Bartle und Spielgenres untersucht. Die Aus- wertung zeigt, dass der Sound zwar nicht den Spielspaß, das Interesse an der Story oder die Motivation weiterzuspielen steigert, aber das Spiel immersiver gestaltet. Auch die Pulsmes- sung zeigt keine deutlichen Unterschiede zwischen den Gruppen. Frauen und Personen, die viel spielen, scheinen allerdings stärker von Sound beeinflusst zu werden. Abschließend wird eine Übersicht auf mögliche fortführende Studien und die zukünftige Entwicklung von Video- spielmusik gegeben. Hinweis: Aus Gründen der besseren Lesbarkeit wird auf die gleichzeitige Verwendung männlicher und weibli- cher Sprachformen verzichtet. Sämtliche Personenbezeichnungen gelten gleichwohl für beiderlei Ge- schlecht. Julia Seibicke I Hochschule Offenburg offenburg.university Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die Bachelorarbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt und die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indi- rekt übernommenen Gedanken als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. -

Interviews with Jason Graves, Garry Schyman, Paul Gorman and Michael Kamper

Fear and the musical avant-garde in games: interviews with Jason Graves, Garry Schyman, Paul Gorman and Michael Kamper Helen R Mitchell The University of Hull Introduction In recent years a number of notable and hugely popular game titles have emerged which utilize the resources of avant-garde1 composition and aleatory2 composition in particular to instill varying states of fear and tension. Two particularly noteworthy composers who have drawn inspiration from this musical heritage, whilst also achieving popular acclaim, are Jason Graves3 and Garry Schyman.4 Interestingly both composers are classically trained and studied at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles; Graves as a graduate of the Scoring for Motion Pictures and Television program (Thornton School of Music) and Schyman as a composition undergraduate of the same school, an education which was supplemented by private tuition with George Tremblay after graduation. Both composers have scored music for film and television as well as games, but currently channel most of their energies into music for games. The range and diversity of titles credited to them has resulted in a fairly eclectic mix of musical outputs,5 each of which has been dictated by the most appropriate musical approach for the needs of the project in hand. Both composers are well recognized for their work; Garry Schyman has received multiple awards, including the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences award, ‘Best Original Score’, for Bioshock (2K Games) - part of a ‘triple A’ franchise. Jason Graves is an Academy Award- winning (BAFTA) composer who has scored ‘triple A’ franchises such as Tomb Raider (Square 2 Enix) and Dead Space (Electronic Arts) and has also received numerous other awards for his work.